Chapter 7 – Shambaugh: Personalization in Education

Personalization in Education

In an Upper Arlington High School senior English class, students sit in a glass-walled lab with their laptops poised, ready for research. A media specialist is sharing information about databases and resources, and setting up appointments with students for reference interviews where students can discuss their needs and she can direct them further to online and in-library materials. Personalized learning is a district goal in Upper Arlington, and while 1:1 technology access helps teachers and students personalize their learning experiences in new ways, a pedagogical movement towards a learner-centered classroom was introduced hundreds of years ago.

History of Personalization

An early education philosopher, John Locke, published Some Thoughts Concerning Education in 1693. Many know of his famous characterization of the human mind as a blank slate, onto which experiences and are written. Locke advised that teachers and parents “cherish curiosity” (Gibbon, 2015). Locke expressed the importance of connecting learners to curriculum and his writing suggests that a good teacher “seizes the moment when the child is “in tune,” engaged, and responsive” (Gibbon, 2015). While he did not specify personalization for students, Locke did note the differences in mind and temperament and wrote,”Some men by the unalterable frame of their constitution are stout, others timorous, some confident, others modest, tractable or obstinate, curious or careless, quick or slow” (as quoted in Gibbon, 2015). Acknowledging the differences in students’ interests and learning styles was a breakthrough that led other theorists to consider how these differences should impact education.

Following Locke’s death, Jean-Jacque Rousseau introduced naturalism or natural education as a means for learners to follow their interests and inclinations. He published Emile in 1762, which provided a context for how natural education cultivates happiness, spontaneity, and curiosity. In the spirit of spontaneity, children are discouraged from forming any sort of habits (Gianoutsos, 2006). Rousseau determined that a child should be “master of himself and, as soon as he acquires a will, always to carry out its dictates,” and therefore, “The child is meant to follow only the natural inclinations, and thus he is capable of observing natural habits” (Gianoutsos, 2006). Personalization in education is rooted in this same premise that children are engaged in tasks when they have more input and are pursuing topics of their own will and interests.

Nearly 80 years after Jean-Jacque Rousseau’s death, John Dewey was born. John Dewey became one of the most significant educational theorists of his era (“Only a Teacher: Schoolhouse Pioneers,” n.d.). He advocated a child-centered approach to education, rather than a curriculum-centered design. He wrote that teachers need to take into account the differences in children, and understand that each child has unique experiences that impact his or her learning (Neill, 2005). Dewey believed that education can’t be something that is given to or done to a child, but rather than a child must engage with an experience to learn. Dewey therefore believed that learning should be “grounded in experience and driven by student interests” (Boss, 2011). Dewey’s work led to the inquiry model, driven by student interests.

This concept of a student-centered approach to education continued with Maria Montessori and Jean Piaget. Montessori, a physician and child development expert, developed a similar, experienced-based method to early childhood education. Piaget, a developmental psychologist, studied how students construct meaning from their experiences. His ideas led to the constructivist approach, “in which students build on what they know by asking questions, investigating, interacting with others, and reflecting on these experiences” (Boss, 2011).

Student-centered approaches, such as the inquiry model, constructivist model, and experiential learning, are the groundwork that created our current concept of personalization in the classroom. Personalization can encompass all of these ideas and more, with student’ passions transforming education from teacher-centered to learner-driven (Bray & McClaskey, 2014).

Personalized Learning Today

Personalization is a buzz word in the education field today. One problem is that while personalized learning is widely discussed, it lacks a clear definition among teachers and districts. Even more confusion occurs when personalization is thrown into the mix of terms like differentiation and individualization.

Barbara Bray and Kathleen McClaskey, part of a team of educators and presenters with an organization called Personalize Learning, created a chart that clarifies the differences and similarities between personalization, differentiation, and individualization. Most notably, in personalization the learner: drives his/her own learning; connects learning with interests, talents, passions, and aspirations; actively participates in the design of the learning; and identifies goals and benchmarks. The learner is actively engaged with all components of learning. Conversely, in differentiation and individualization, the teacher is responsible for providing instruction, accommodating individuals or groups of students, adjusting curriculum, designing instruction, and identifying objectives (Bray & McClaskey, 2014). In differentiation, the teacher may identify the same objectives for groups within a classroom (think “high” group, “low” group). However, with individualization, the teacher may identify the same objectives for all learners with specific objectives for learners who have one-to-one support (for students on an Individualized Education Plan, for example). In personalization, the learner “becomes a self-directed, expert learner who monitors progress and reflects on learning based on mastery of content and skills”, while in individualization and differentiation, the teacher uses data and assessments to determine next steps in teaching and learning (Bray & McClaskey, 2014).

As our student population becomes more diverse in academic ability, background, and language, personalization seems like it may be a way to meet the needs of each student. Technology solutions that offer teachers the opportunity to customize lessons based on students needs and collect data on individual progress are readily available (Cavanagh, 2014). There are several software companies and platforms that are trying to connect their products to the idea of personalization, when really they may be helpful in individualization or differentiation. Take for example, the video embedded below featuring “New Classrooms’ Personalized Learning Model – Teach to One: Math.” Using Bray and McClaskey’s model described above, consider where this model fits best: personalization, differentiation, or individualization? As an instructional leader in Upper Arlington Schools, I am responsible for vetting iPad app and MacBook software requests from teachers in my three buildings. There are many requests for programs that customize levels in math and spelling, for example. The programs offer independent practice and skill review opportunities for our students, and that’s important, but is that personalization? According to Bray and McClaskey’s model, it’s not. It’s individualization, which is valuable too, but doe not take the place of a personalized educational experience.

There are obstacles to personalization because it requires more than just the right program or the right technology; it requires a shift in pedagogy. When teachers were students themselves, they were likely taught by the “sage on the stage” method, where a teacher stood in front of the class and disseminated information. In a student-centered classroom, everyone has the opportunity to become the “sage” as students make decisions about their own learning. Sir Ken Robinson’s Ted Talk can help us consider the mindset required for a shift this monumental.

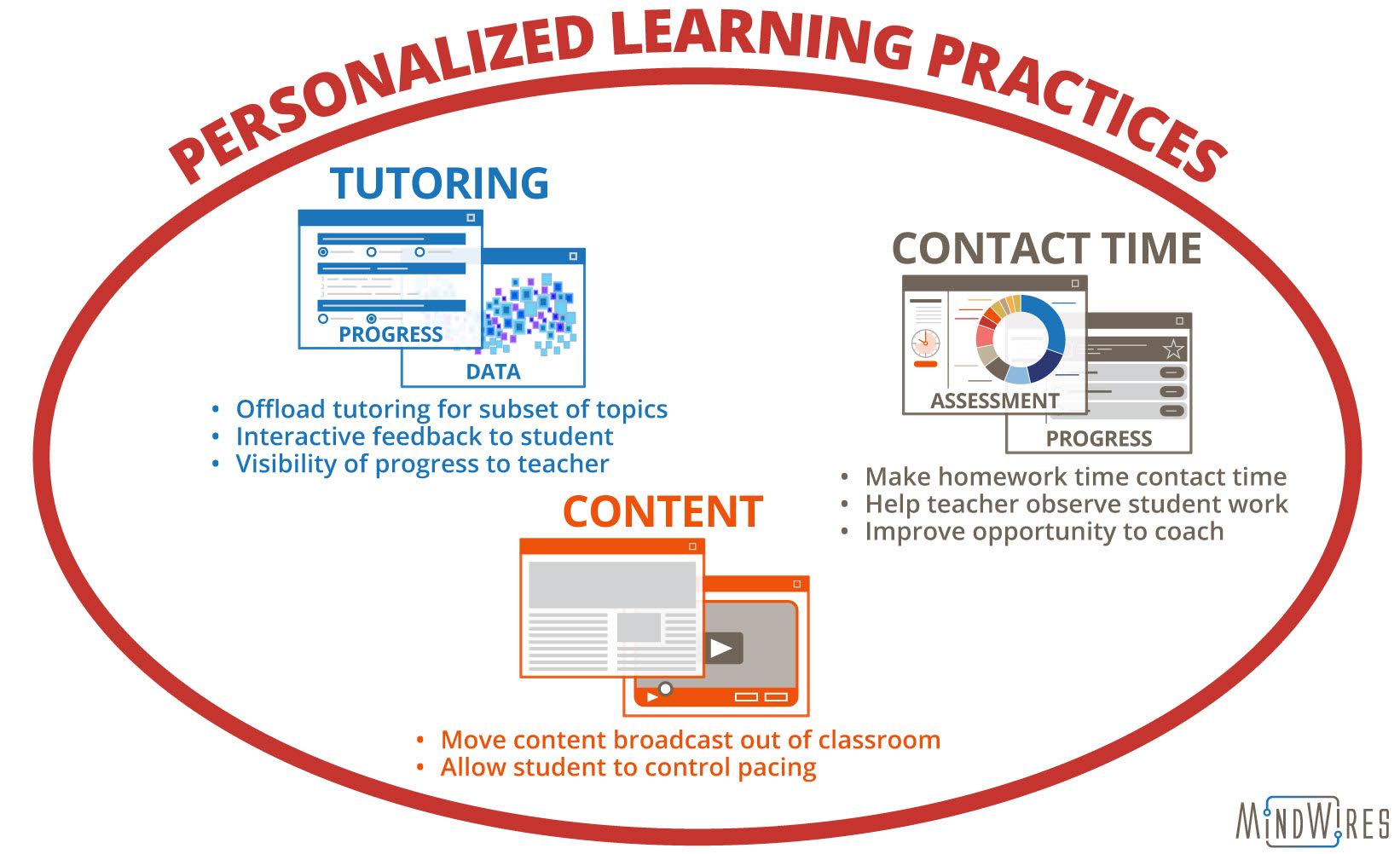

There are additional strategies that allow technology to become “an enabler for increasing meaningful personal contact” (Feldstein & Hill, 2016). Michael Feldstein and Phil Hill, partners at MindWires and EDUCAUSE, conducted a three year study examining personalized learning and found some “technology enabled educational practices” that they then used to create a framework as a way of considering how technology supports personalization. They found that technology eliminates some barriers to one-to-one teacher/student interactions when leveraged appropriately. The three main strategies that they identified concern tutoring, contact time, and content, as noted in the graphic below. In terms of tutoring, Feldstein says that technology can be used to reinforce some skills through adaptive learning software and other interactive tools. Technology allows for increased contact time by allowing teachers to “flip” classrooms where teachers can better support students as they are working, especially within digital products. Feldstein adds, “Further, personalized learning often identifies meaningful trends in a student’s work and calls the attention of both teacher and student to those trends through analytics” (Feldstein & Hill, 2016). These personalized learning practices are utilized in Upper Arlington Schools, and due to 1:1 technology, teachers are finding ways to be more creative with their time. Documents are shared digitally so that teachers can access them in real time and offer immediate feedback; teachers are posting resources to Schoology, our learning management system, so that students can review lessons from home. However, it’s the work itself that must be student-driven.

Suggestions for Implementation

Suggestions for Implementation

Personalization means that students need to be considered first in teaching and learning. It is a teaching and course design method that, “requires students to assume a large share of responsibility for conducting inquiries, applying knowledge, and making meaning of what they have learned” (Gorzycki, n.d.). San Francisco’s Center for Teaching and Faculty Development suggests that instructors consider different options when designing instruction (Gorzycki, n.d.). While the center does not identify one particular technique as a necessary component, they offer several examples of student-centered activities on their website that are all suggestions that move away from traditional lecturing, such as using class time to allow students to debate, and engaging students in original research opportunities.

In Upper Arlington Schools, personalization is part of our strategic plan and led to the decision to move to 1:1 technology access. Our high school Research & Design Lab and Active Classroom are great examples of how technology alone doesn’t personalize education, but how the right mix of technology and multi-functional spaces can allow teachers to make the shift in pedagogy that allows them to create more student-centered experiences. The active classroom is full of flexible seating so that students can easily move from individual work to groups. There are spaces all over where students are free to take notes and jot ideas (including on the walls). The R & D Lab is as much a conceptual space as a physical one, and students are encouraged to bring forward ideas to discuss, prototype, iterate, and support. It’s still possible to stand in front of flexible seating and arrange students in rows. It’s also still possible to make them put their laptops away and spend the day lecturing, but the right tools make it easier for teachers to create opportunities to engage students, to encourage passion projects, and to personalize learning.

References

Boss, S. (2011, September 20). Project-based learning: A short history. Retrieved from

https://www.edutopia.org/project-based-learning-history

Bray, B., & McClaskey, K. (2014, June 25). Updated personalization vs. differentiation vs. individualization chart version 3. Retrieved from http://www.personalizelearning.com/2013/03/new-personalization-vs-differentiation.html

Cavanagh, S. (2017, February 09). What is ‘personalized learning’? Educators seek clarity. Retrieved from http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2014/10/22/09pl-overview.h34.html?r=319993521

Feldstein, M., & Hill, P. (2016, March 7). Personalized learning: What it really is and why it really matters. Retrieved from http://er.educause.edu/articles/2016/3/personalized-learning-what-it-really-is-and-why-it-really-matters

Fisher, J. F. (2017, January 21). Education Innovation in 2017: 4 Personalized Learning Trends to Watch « Competency Works. Retrieved from http://www.competencyworks.org/uncategorized/education-innovation-in-2017-4-personalized-learning-trends-to-watch/

Gianoutsos, J. (2006, Fall). Locke and Rousseau: Early childhood education. Retrieved from https://www.baylor.edu/content/services/document.php?id=37670

Gibbon, P. (2017, March 10). John Locke: An education progressive ahead of his time? Retrieved from http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2015/08/05/john-locke-an-education-progressive-ahead-of.html

Gorzycki, M. (n.d.). Student-centered teaching. Retrieved from https://ctfd.sfsu.edu/content/student-centered-teaching

Moore, L. (2016, October 7). Active Learning Lab [Photograph found in Upper Arlington]. Retrieved from http://uahsr-d.blogspot.com/2016/10/breaking-through-cement.html

Neill, J. (2005, January 26). John Dewey, the modern father of experiential education. Retrieved from http://www.wilderdom.com/experiential/ExperientialDewey.html

Only a teacher: Schoolhouse pioneers. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/onlyateacher/john.html

Steel, S. (Director). (2014, December 31). John Dewey, Inquiry, & Progressive Education [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gsJoEO5Q8xw