Main Body

Chapter 9 – Robbie McCord – The evolution of feedback in a fully-online course for English language learners

How has the fully-online Writing the University Application Essay (WUAE) course at the University of Pennsylvania’s English Language Programs evolved over time to better facilitate the provision of more effective feedback?

Introduction

In classroom second language learning, one of the most important considerations on the teacher’s part should be creating interactional opportunities with language learners. Interaction plays a facilitative role in language acquisition (Ohta, 2000). One of the main reasons for this is the fact that through interaction, a learner can receive feedback on the success (or lack thereof) of the language that he or she has produced (Gass & Selinker, 2008). The feedback that the teacher provides serves as language input for the learner—it should be noted that fellow students can and do provide feedback that is equally useful. According to the Input Hypothesis, second languages are acquired through input of the language being learned; in order for the language to be acquired, though, the language must be comprehensible (Krashen, 1985). The making of language comprehensible to language learners has been the subject of countless articles in the field of second language acquisition (Gass & Mackey, 2015). In the classroom, because much of the input that students will receive is feedback, a very large task of the language teacher is to make feedback useful for the student.

One critique that language teachers—and teachers in general—face is that they spend too much time talking rather than facilitating students’ interactions. However, feedback, when done strategically, can encourage more student talk and actually help to move the classroom dialogue forward (Miao & Heining-Boynton, 2011). Online environments are, of course, different, and considerations need to be made that take this into account, especially when one’s learners’ first language is not the language of instruction. Coryell and Chlup (2007) developed four themes which developers of online courses for English language learners should consider. These themes were (1) preparation, (2) individualized, student-centered instruction, (3) support, and (4) collaboration.

Preparation included tasks that took place before the course was implemented. This included research, procurement of the necessary hardware and software, and marketing. Other tasks related to ensuring that the student population had sufficient computer literacy fluency in order to be successful. While this is important for all students, it may be even more so for students for whom English is not their first language.

Individualized, student-centered instruction is important in all educational settings. It is certainly important in English language classrooms, where student-student and student-teacher interaction makes language more salient, and thus more likely to be acquired (Long, 1996). Because of this, teachers in the Coryell and Chlup study emphasized the need for e-learning tools that facilitated student-centered instruction. One such example of this was the realization that students’ English proficiency levels in the same class varied quite a bit,so technology was used to differentiate the instruction that students received.

The theme of Support is related to all types of support, from student and instructor assistance, to funding, to technical help. Specifically, technology was used to provide student support in the form of tutors, extra mini classes, job searches, etc. Technology was used for instructor support in the form of professional development, much of which was focused on hardware, software, or pedagogical approaches.

The Collaboration theme focused on cooperation between all players—students, teachers, staff, and administrators. One example of this is instructor-instructor collaboration. Instructors met with each other and other administrators to discuss ideas related to language instruction, technology, and the more-efficient incorporation into instruction in order to better serve students.

From the Coryell and Chlup study, it is clear that online courses for English language learners requires careful thought. This chapter is a look at one such class and the considerations that the language program that developed the class made in how to implement student feedback.

The Context

The English Language Programs (ELP) at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) is located within UPenn’s College of Arts and Sciences. One of its main goals is to provide instruction in English to students who want to improve their English language proficiency (University of Pennsylvania English Language Programs, 2017). Students often take classes with the goal of gaining admission to UPenn or other American universities. Many students also are businessmen and women from around the world who want to improve their business English skills. The ELP draws hundreds of students from Saudi Arabia, Korea, Japan, Brazil, China, Turkey, and many other countries.

The online course at the UPenn ELP that is the focus of this chapter was developed in partnership with the Penn Online Learning Initiative. The Initiative began in 2012. Its staff work with UPenn instructors and course developers in developing online content. Today, there are over 135 courses offered in partnership with the Initiative and over 3.5 million learners worldwide (Penn Online Learning Initiative, 2018).

The Course

Writing the University Application Essay (WUAE) is a fully-online course that is offered through the UPenn ELP. Thanks to permission given by the UPenn ELP, a video that provides more background to the course can be found here. The course is offered one to two times per year and runs for five weeks. The course was first offered in 2014 and has been taught by two instructors. Interestingly, according to one of the course’s instructors, though there is today an in-person WUAE course, it was the online course that inspired the creation of the in-person course.

The course’s website describes the university application essay as one of the most important aspects of the admission process and that therefore the essay is the applicant’s one chance to show why the applicant would be a “positive addition to their school or community” (Writing the University Application Essay, 2017). The course is intended for international freshman applicants to universities in the United States. The structure of the course begins by taking a broader look at the college application and the essay’s place within that application. Then, the course narrows its focus to encourage students to devise interesting topics and begin crafting their own essays. Students participate in writing workshops and receive individualized feedback from their instructors.

The Project

The goal of this project was to better understand how the UPenn ELP’s WUAE course has been implemented. Given the important role of feedback in language learning, the focus was particularly on how feedback is given to English language learners in an online setting and how the role and delivery of feedback has changed in the course since the course’s inception. In order to gather data, a questionnaire was developed which would be used to interview instructors of the WUAE course. Items on the questionnaire were created using a number of sources, including relevant literature, the UPenn ELP website, and, having taught English as a second language at UPenn and elsewhere, my own teaching experience.

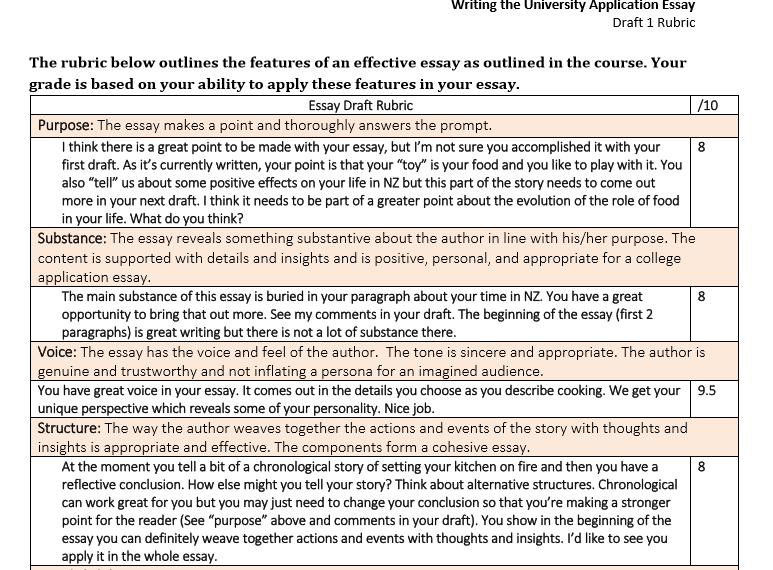

Drawing specifically from Coryell and Chlup’s (2007) paper, the questionnaire was organized around four themes: preparation, student-centered instruction, support, and collaboration. A table with the breakdown of questions is below:

| Theme | Number of questions | Example |

| Preparation | 3 | Are instructors trained in how to effectively provide feedback in an online environment? If so, how? |

| Student-centered instruction | 5 | How is your feedback reflected in students’ writing? |

| Support | 2 | How are students or instructors who experience technical problems supported? |

| Collaboration | 1 | Is feedback encouraged between students? If so, how? |

The following is a large sampling of responses to the questionnaire from a UPenn ELP WUAE instructor:

Questionnaire:

Q: How many instructors teach the course? Are they trained in how to effectively provide feedback in an online environment?

A: I’ve been the primary instructor in the course. We had another instructor teach it in Fall 2014. I trained the teacher by going through the course with him and enrolling him in the previous so he could poke around see my feedback to students on various assignments.

Q: How are students or instructors who experience technical problems supported?

A: The course was supported though Online Learning. They support all Penn’s online courses and MOOCs. There were some technical issues I had to deal with myself. In the last run of the course (Summer 2017) one of the students from China was having trouble watching the videos because of the way they were hosted so I had to upload them to google drive and send him a link.

Q: What technologies are used to provide students with feedback in the fully-online WUAE course?

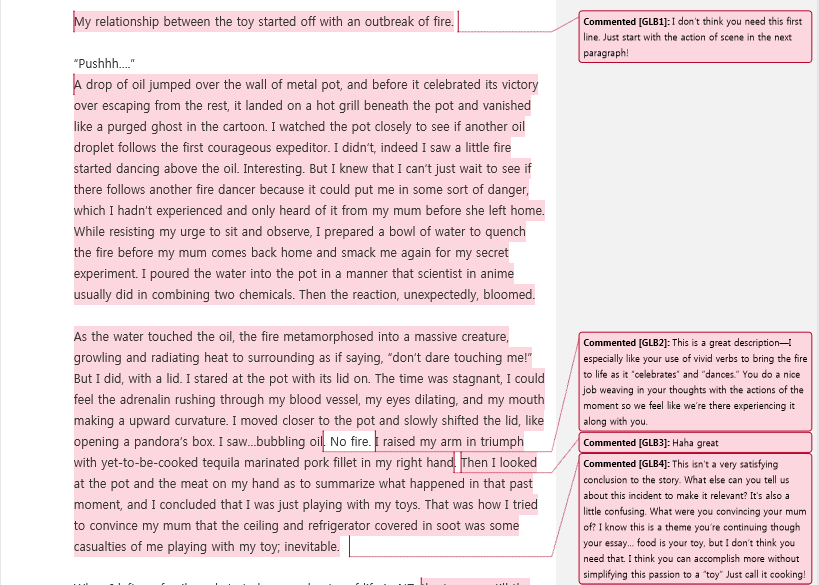

A: The course is run on Canvas. So some feedback was given through the SpeedGrader tool. Until recently, Speedgrader used Crocodoc to allow instructors to give feedback—it’s a document viewer that allows for comments, highlighting, and light editing/annotating. Canvas has a new SpeedGrader tool now that has a little more functionality. I’m not sure what it’s called. Feedback aimed at groups was also given through discussion board posts.

Q: How did you provide feedback in the online WUAE course when first teaching the course? How do you provide feedback now? Can you explain the changes you’ve made over time in delivering feedback?

A: Students receive extensive individualized feedback on their work. I don’t think the way students receive feedback has changed much since the first run of the course. I give them feedback on their work by filling out rubrics and also commenting directly on their drafts using either Canvas or Word.

Q: Is it more challenging to provide effective feedback in an online course? Can you describe the challenge(s)?

A: It’s more difficult to give effective feedback in an online course because it requires much more individualized feedback. In the online course they don’t have the benefit of live “writing workshop” in which the student would have a turn at having the whole class read their draft and discuss the strength, weaknesses, and opportunities in the writing. In the live course, my feedback on their work often reinforces the ideas from class so it doesn’t need to be so extensive.

Because the online course is only 5 weeks and we want them to be able to do a series of Writing Preps along with 3 full drafts of their essay, there isn’t time for the same kind of writing workshop as the live course. Instead, students read and discuss sample essays only. I also provide a lot of feedback on their “feedback” of the sample essays to make sure they have the right idea going into their own essays. Students can post their drafts to the discussion board for feedback from their peers, but I don’t think anybody ever has.

Q: How is your feedback reflected in students’ writing?

A: The rubric for the drafts is very specific and I fill it out with specific advice for improving the essay in different areas. On subsequent drafts, I’ll open up the same rubric and provide updated comments on how well or poorly they followed the advice with an updated score in that area.

Q: What tasks is feedback provided on? Do you deliver feedback differently for different tasks?

A: For the essay drafts, feedback is provided the same way for all 3 drafts. Feedback on the “Writing Preps” is different for each assignment. All involve a good amount of commentary.

Q: How would you improve the way that feedback is provided in the online course?

A: Good question! At the moment all feedback is asynchronous. Students have the option of scheduling a live conference (skype) to discuss their work, but usually the asynchronous feedback seems to be enough for them to revise their drafts effectively. I think more strategic live conferencing could be beneficial. I also think there are some other more useful ways to give asynchronous feedback that isn’t entirely “written.” I’ve been wanting to try using Jing to go over my feedback in a video recording in the same way I’d go over my feedback with a student in my office. In this way I could read and explain the feedback while pointing out areas in the essay visually. However, because of the time constraints, I’ve never done it. Usually drafts are due on Sunday at midnight and I need to have feedback to all students by Wednesday so that they have time to write their next draft by the following Sunday. So I only have 2.5 days to give the whole class extensive feedback while also balancing my live student obligations. I think being able to record my feedback for them to listen to would be helpful. I think I may have tried it once a couple years ago.

Q: Have the tasks that students participated in changed over the years, and if so, how has the feedback provided to students been reflected in these new tasks?

A: There have been some new tasks but the nature of the feedback hasn’t changed.

Q: Is feedback encouraged between students?

A: On the discussion boards students give feedback on sample essays. They debate the quality of the essays based on features also highlighted in the essay rubric. Once a few comments have been posted I’ll give feedback so we can all come to some similar conclusions about the sample.

Q: Does technology make it easier, more difficult or the same in giving feedback?

A: I give feedback for the live course in the exact same way: comments on their draft and feedback and scoring in a rubric, so I’d say it’s the same. In the live course there are more opportunities for live/synchronous discussion which may help them to understand the feedback better, but the feedback itself isn’t different.

Q: Is there anything else that you can tell me about how the practice of providing feedback has changed since the course was first implemented?

A: Maybe some elements in the rubric have changed slightly, but there haven’t really been changes in feedback practices. There have been some changes in the Canvas platform that effects feedback slightly but nothing that I can point to that is worth mentioning.

Discussion

Here I would like to discuss some themes that emerged from the interview. First, Coryell and Chlup (2007) indicated that support was one of the most important aspects to consider when developing an online course. The interviewee noted that support is given by Penn Online Learning, which supports all of Penn’s online courses, but she also has had to problem solve herself. This self-sufficiency is no doubt very important when running an online course, as one may not always be able to ask someone else for assistance. The instructor’s self-sufficiency is probably a result of having taught the course (and in the UPenn ELP) for a number of years.

In regards to feedback, another theme that became apparent is the sense that giving feedback in a “live” environment is easier than in an online one. There are more opportunities for feedback in a traditional classroom. This is intuitive when one things about it: In a traditional environment, a student is getting feedback directly from the teacher and other students but also indirectly as the teacher responds to other students. In a sense, feedback is all around them. In the online environment that is described in this project, students primarily just get feedback on their individual assignments. As the interviewee mentioned, students do have the opportunity for one-on-one Skype sessions, but the majority of feedback comes on students’ papers. It is because of this that the teacher needs to make extensive comments on the papers. This can be difficult, which is probably why the interviewee mentioned using other feedback media (e.g. Jing).

A final theme that I’d like to discuss (and the most interesting) is the fact that the course and feedback methods seem to have changed very little since the course’s inception. The fact that the course has changed little may be for the most part out of the teacher’s hands. Such decisions are likely made by ELP administrators as well as the Penn Online Learning Initiative. However, the teacher does have the ability to alter feedback techniques and does hint at the fact that in the future this may change. For example, since the course’s start, the majority of feedback has been in the form of comments on students’ papers. Additionally, students are given the opportunity for one-on-one feedback in live sessions via Skype. Also, students respond to each other in discussion boards. This extensive feedback seems helpful, but also is likely time consuming. Because of this, the teacher mentioned incorporating other technologies to provide feedback. Due to the amount of detailed feedback that this course requires, I am surprised that for the approximately five years that this course has existed that there have been relatively few changes in the form of feedback delivery.

Conclusions

The purpose of this project was to better understand how a fully-online course for English language learners operated, taking into account the special considerations that need to be made for students for whom English is not their first language. Specifically, the goal of the project was to look at how the role and delivery of feedback has evolved since the course’s inception. I used research literature to guide both the discussion within this project and the creation of the questionnaire that was used to gather data from a teacher at the University of Pennsylvania’s English Language Programs. Some themes emerged around course support, student-centered learning, course preparation, and collaboration. In regards to this course, the teacher demonstrated that while she did from time to time rely on administrative technical support, she was fairly self-reliant in her own ability to problem solve. Secondly, according to the teacher, it is more difficult to give feedback in the fully-online course than in a “live” course. This is because she needs to be more explicit in her feedback since students are only getting feedback from one source (their course papers). Finally, it was discovered that, although the course has been around for a number of years now, its structure and the mechanisms for giving feedback have changed very little. The teacher did, however, note some things that she would consider modifying in the future.

When teaching English language learners, there are a number of considerations that need to be made. This is even more true when teaching in a fully-online environment. It is my hope that this project has illuminated some of these important considerations.

Coryell, J., & Chlup, D. (2007). Implementing e-learning components with adult English language learners: Vital factors and lessons learned. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 20(3), 263-278.

Gass, S.M., & Selinker, L. (2008). Second Language Acquisition: An Introductory Course. New York: Routledge.

Gass, S.M., & Mackey, A. (2015). Input, Interaction, and Output in Second Language Acquisition. In B. VanPatten & J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in Second Language Acquisition (pp 180-205). New York: Routledge.

Krashen, S. (1985). The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications. New York: Longman.

Long, M.H. (1996). The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W.C. Ritchie & T.K. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of research on language acquisition: Vol. 2. Second language acquisition (pp. 413-468). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Miao, P., & Heining-Boynton, A.L. (2011). Initiation/Response/Follow-up, and response to intervention: Combining two models to improve teacher and student performance. Foreign Language Annals, 44(1), 65-79.

Ohta, A.S. (2000). Rethinking interaction in SLA: Developmentally appropriate assistance in the zone of proximal development and the acquisition of L2 grammar. In J. Lantolf (Ed.), Sociocultural theory and second language learning (pp. 51-78). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Penn Online Learning Initiative. (2018). Facts and Figures. Retrieved from: https://www.onlinelearning.upenn.edu/about/facts-figures/

University of Pennsylvania English Language Programs. (2017). Mission Statement. Retrieved from: https://www.elp.upenn.edu/about/mission

Writing the University Application Essay. (2017). Course description. Retrieved from: https://www.elp.upenn.edu/wuae