Main Body

Chapter 11 Learning Chinese online: a snapshot of the pedagogy-driven online Chinese teaching approach at Michigan State University- Zilu Jiang

Introduction

5:00 p.m. East Lansing, MI.

“Nǐ hǎo, Jason. (Hello, Jason)”

“…”

“Nǐ hǎo, Jason. Can you hear me?”

“… Nǐ hǎo, Jiang laoshi(Ms. Jiang). Can you hear me? (Jason is typing) ”

Ms Jiang is providing her third Chinese lab session today in the office of Confucius Institute at Michigan State University. Eight American high school students gather online in the AdobeConnect meeting room, some of them are using the computer lab in California while some are sitting in the car using their cellphone to join the online language lab session. Different from a traditional class, Ms. Jiang is not going to lecture today. Starting from the review of the learning content in the preview assignment, she raised a discussion first and guide students to participate in a series of language tasks, raising from linguistic drills, meaningful tasks to communicative tasks. Students, instead of sitting passively or sometimes daydreaming in front of the screen, actively interact with Ms. Jiang and their peers. Each week, they join the mandatory online meeting once to practice Chinese and spend other weekdays on a self-paced study in the online learning management system Blackboard. As many people start to notice the challenges and opportunities of globalization, there has been an increasing demand for foreign language education. However, the shortage of native speakers and the scattered distribution of language learners have challenged the face-to-face brick and mortar setting. Online language learning, turns out to be a feasible solution for the needs of learning a foreign language. Not just these eight students start to learn a language online, almost 360 American middle and high school students are enrolled in 2017-2018 in the online Chinese learning program provided by Confucius Institute at Michigan State University (CI-MSU) and Michigan Virtual. This chapter will focus on presenting the CI-MSU online Chinese learning program since 2006 with a brief history introduction and a discussion on its pedagogy-driven based design, especially in investigating what innovations the CI-MSU have contributed to the online Chinese language learning and the designing philosophy.

Background

The growth of technology has transformed the way people learnt and teach. It’s particularly true for language education, in which interactive technologies has provided more learning opportunities to people who may not have access to the language class. Online learning, as one of the major trends in technologies, has afforded many activities for language learning and teaching.

Leading by the Michigan Virtual and Michigan Legislature, Michigan is at the forefront of K-12 online education that requires all students to have online learning coursework before graduating from high school since 2006 (Watson et al., 2009). The online learning experience has been incorporated into the required credit course of the Michigan Merit Curriculum. The curriculum not only emphasizes the online course experience but also requires students to complete 2-credit language course other than English in grades 9-12 (Michigan State Board of Education, 2010). The circumstance has called out the birth of an online language program for high school student in Michigan.

In May 2006, the Confucius Institute at Michigan State University (CI-MSU) was established in partnership with Michigan State University, the Office of Chinese Language Council International (Hanban) and The Open University of China, offering multiple online languages programs and services to meet the rising demand of Chinese language learning. The CI-MSU online program, the first Confucius Institute online Chinese class across worldwide, is also a collaborative effort between the CI-MSU and the Michigan Virtual, which is a non-profit online education and training corporation funded by the Michigan Legislature.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7-roktkJH8w

Video 1. CI-documentary 2014 (CI-MSU,2014)

Since August 2006, the cooperation between CI-MSU and MVU has brought out five levels of online Chinese courses (Chinese 1A, 1B, 2A, 2B, 3A, 3B, 4A, 4B, AP1, and AP2) to middle and high school students. Teachers are all Chinese native speakers recruited from the Headquarter of Confucius Institute. Besides the academic online learning course, CI-MSU also developed an online immersive language learning gaming virtual world called “Zon/New Chengfeng” in 2008-2013, as a fun way to interact with target language and culture. As a leading organization in providing innovative language programs, CI-MSU has been chosen as the Confucius Institute of the Year Award offered by the Chinese Ministry of Education in a consecutive three years.

Online learning programs

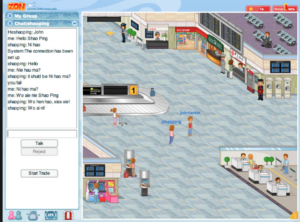

Zon

“Zon,” a Massively Multiplayer Online Role-playing Game (MMORPG), was adopted as an instructional platform for online teaching during 2008-2013. Its developing process was supported by Michigan State University and the Office of the Chinese Language Council International. In this browser-based gaming virtual world, users can create an avatar and immerse themselves in a target language environment. Situated in Beijing, it presents the player simulation of daily life in China where learners experience Chinese culture through travelling. By interacting with other players and the non-player character in the game, students participate in the learning of Chinese language through daily life communication, such as taking a taxi, shopping and eating out. The role of the students in the system can advance from the tourist to the resident and finally become a citizen of the virtual world as they pass through the quests in the system. Students check the progress announcement posted with suggested learning tasks and contents before starting the game. They not only practice the language skills in the simulation system but also join the synchronous Zon-class where they can have a 10-15-minute lab session with the instructor once per week(Chen, 2013). In addition, students can also post questions anytime in public chatting room or through individual chat in the virtual world. Student-student interaction is also achieved via Avatar chat window, both through text and voice chat.

“Games are supposed to be fun and educational, with this one, we have struck a good balance.” Said Zhao (as quoted in Henion & Geary, 2008), the former executive director of CI-MSU who initiated the program. Apparently, the gaming system has enabled a naturally occurred social and communicative simulated target language environment despite the distance. In contrast to the traditional drills and exercise, language learning in ZON is initiated around the purposeful communication. The integrative use of language (exchange meaning) take precedence over the separated linguistic form (grammar and pronunciation) that make the learners feel more related to the authentic language tasks. It was also used as a tool to foster cross-cultural communication and strategic social competence by helping learns to set a communication goal, planning responses and reduced the fears of making mistakes. The teacher-student ratio can reach to 1:20(Chen, 2013), however, due to the limit interaction time, the instructor may not be able to tailor the guidance to each student’s needs, not even have to provide feedback to the assignment since no extra work is needed. Generally speaking, it’s still a fun way to motivate students or can be used as a supplementary platform. But more scaffoldings on structured practices should be offered to be desired. In 2013, the program was ceased after Michigan State University issued the sale of the license to a private company.

Online courses

The online courses were delivered through Blackboard offered jointly by the CI-MSU and Michigan Virtual. The CI-MSU integrates both synchronous and asynchronous learning, where students complete four-day self-paced study and join the lab session with instructors once per week. The whole course format is designed to cover the training of interpretive, communicational and presentational language skills. With an emphasis on improving the language skills comprehensively, the CI-MSU developed a unique online learning environment that not only makes use of the technology but also integrated the traditional components in the classroom through which students can experience the preview of the lesson, structured drills, and practice, interactive tasks, submitting assignments and formal assessment. The maximum number of the students in the lab session was eight to ensure enough individual practice time. In this way, the courses capitalize on the advantages of both the technologies and human interactions for language learning.

It’s noteworthy that instructors also design study guides and assign differentiated tasks based on students’ learning progress and levels. According to Dr. Jiahang Li, the associate director of CI-MSU, what students like most are “the flexibility of self-learning progress during a week,” “the seamless connection between the asynchronous and synchronous session” and “ being able to communicate with instructors.” (Jiang, Zheng, & Li, 2016). Students find they have enough opportunities to practice on what they’ve learned in the previous self-paced study. The recurrence of new learning content is important especially in the online learning environment where teachers are not always by their side. This learning format also requires the teacher to incorporate the concept of self-regulation into the design of learning process since they have more autonomy in the self-study stage. In another word, the student needs to be scaffolded as a more responsible learner.

“We try not to do too much drill-and-kill,” Romig says. “Language isn’t fun if you’re just listening and repeating back. We try to get them thinking through the language. They have the opportunity to practice and speak out dialogue, but we want our students to be able to use that language in a real-world context.”(Miller, 2016).

The target students of the CI-MSU online Chinese courses are mainly U.S. middle and high school students between the ages of 12-18 years. This unprecedented course format has been beneficial to students who have limited access to Chinese language learning due to the constraints of time, space and academy. “Over 4000 American high school students from over 20 states have joined the Chinese online course”, said Dr. Jiahang Li, “our mission is to use the technology to bridge the gap in communications, we also continue to re-evaluate and revise the way of content delivering to improve the learning process.” (Li, J, personal communication, Apr.10, 2018). In 2015, the research team at the CI-MSU undertook an innovative online flipped classroom project, unveiling the new online language learning experience and language skills training opportunities with technologies.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTUh7dGq6Yw

Video 2. The Personal Impact of Online Chinese Learning (Sanborn, 2012)

Developing a pedagogy-driven Online flipped classroom

“I used to adopt the traditional approach into online settings, but it doesn’t seem to work well. I found time management and interaction is a great issue. If I spend the lab session time on lecturing, students will be sitting there and not get enough chance to practice. I think we need to redesign our courses.” said one of the online instructors at the CI-MSU.

Online learning, while making more opportunities and accesses to learning resources, was also found to bring challenges and barriers in language study. Insufficient support for interaction ,oral practice and lack of immediate feedback and teacher physical presence have been the major problem discussed (Jiang, Zheng, & Li, 2016).

In 2015, the research team at the CI-MSU and the author initiated the online flipped classroom at CI-MSU and redesigned the course format with the flipped classroom concept based on the pedagogy-driven approach, with an attempt to increase content-related interactions and enhance teaching presence(Pearson, 2016).

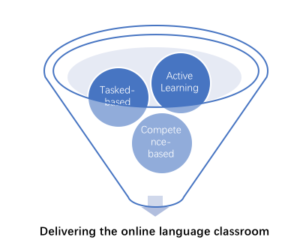

Conceptualizing the pedagogy-driven approach in an online flipped classroom

There have been some attempts to define the online pedagogy for developing online learning environments(Colpaert, 2006; Laanpere, Pata, Normak, & Põldoja, 2012; Radcliffe, Wilson, Powell, & Tibbetts, 2008). Pedagogy-driven approach, as opposed to the technology-driven approach that attempts to formulate a pedagogy based on the advantages and the innovative features of technology, is inspired by learner-centered pedagogical paradigm, involving “a detailed specification of what is needed for language teaching and learning purposes in a specific context, defines the most appropriate method, and finally attempts to describe the technological requirements to make it works” (Coplaert, 2006, p.479). As such, it is proposed to address the needs and goals of learning with correspondent teaching method through the strength of technology.

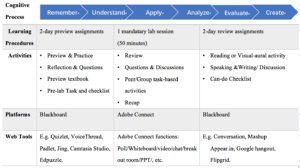

The challenges in online language learning require teachers to create more opportunity for interactive tasks and scaffold students to engage and apply learning concepts actively. “Flipped learning is rooted in social constructivism, which holds that students engaged in communication and interactive activities will learn more effectively” (Li & Jiang, 2017,p.27,). It refers to the process that: 1) what traditionally take place in class is now done outside the class and vice versa; 2) the class time is now spent for active learning where teachers guide students to achieve high-order thinking as it’s defined in Bloom’s taxonomy. With flipped learning approach, online students spend more time on the lower cognitive level of work in preview self-study stage, studying basic learning concepts until they remember and understand, or maybe to apply with structured linguistic guidance. When joining the lab session and learning activity, with the help of the instructor through peer interactions and group problem-solving activities, their cognitive process can be developed gradually to reach the stage of analyzing, evaluating and creating (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001) , the extended practice can also be realized in the self-study review after lab session.

The pedagogical theories foundation

The pedagogy theories below have formed the core philosophy for delivering the online flipped language classroom.

Active learning

It is an instruction that strives to involve students in the engagement with the learning material, participate in the class and collaborate with each other. So rather than simply having students sitting there and memorizing concept, telling students what to learn and how to learn it, it means to get them to learn through that engagement, demonstrating the process, analyzing an argument or apply a concept. Students are involved in “both doing things and thinking about the things they are doing” (Bonwell & Eison, 1991). It’s an effective strategy for both traditional classroom and online learning environment(Li & Jiang, 2017). The shift away from instruction that is professor-centered to the learner-centered process allows students to actively construct knowledge and be responsible for what they learning progress.

Task-based learning

The multimodal online environment has a great potential to facilitate the task-based teaching, and the tasks designed in the web environment can involve online learners into real meaning communication, which simultaneously reinforce their second language acquisition. The realistic “task” implicit in real life situations such as shopping in the mall and greeting co-workers will prompt students to use the target language instead of merely learning it, insofar as such tasks involve listening, speaking, reading and writing. Realistic tasks offer online students an opportunity to change from a virtual role to a concrete one, and thereby to achieve the goal of language learning: communication. Such tasks should focus on meaning that involves the learner in comprehending, manipulating, producing or interacting in the target language (Nunan, 2004). Considered as a means of assimilation, they should be designed as a bridge between the classroom and the real world, and teacher should encourage the use of multiple grammatical structures to achieve task outcomes.

Competency-based learning

Similar to outcome-based education, students learning outcome is frequently assessed. It also gives learners more control over their learning path as it focuses on mastery (Laanpere et al., 2012). Teachers can design appropriate activity based on students’ mastery progress and provided personal guidance along their study pace. Students are allowed to resubmit the work multiple times to demonstrate their competence in presentation, communication, and interpretive skills. In this way, frequent personalized interaction shall be achieved.

Overview of the online flipped classroom model

The flipped classroom model is also named as “2+1+2” format, which is composed of three major elements: 1) 2-day preview assignments with one or two lecturing videos focusing on vocabulary and sentence structures; 2) 1-day mandatory lab session; 3) 2-day review assignment focusing on interpretive activities and presentational activities. The instructor will upload the learning materials to Blackboard and post the study guide each week in the announcement. The lab session is held through AdobeConnect.

Preview

Students learn the new words and sentence structure with the help of Quizlet and VoiceThread/Interactive video. Quizlet is a game-based online flashcard website where students can memorize the words and play words games. Nevertheless, learning vocabulary or grammar in isolation may not ensure students’ readiness for the class or communication more generally. Therefore, grammar and vocabulary learning should be meaning-bearing activities, “tasked with understanding the communicative message” (Spino & Trego, 2015). Interactive videos/VoiceThread is chosen as essential technology tools for delivering the lectures. Instead of sitting in front of the screen listening passively, students engaged in the lectures through interacting with the embedded quizzes, posting responses and questions. Teachers, also facilitate the learning process with feedbacks through Blackboard and VoiceThread platform. Multiple instructional activities are added to VoiceThread to increase student’s engagement. “VT helps me to introduce the words in context. I explain the words in the contexts, so the students can learn the vocabulary by making a connection with the context”, said one of 1A Chinese instructor at CI-MSU(Li, Z, personal communication, June.18, 2016). Interactive video website, such as EDpuzzle, can also generate students ‘learning reports to help teachers analyzing the preview study outcomes.

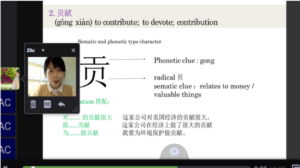

Figure 6 shows how the teacher introduces a new character with its semantic and phonetic clues, helping the student to construct the concept of the new character based on the knowledge they acquired previously. Figure 7 presents an example of how the instructor introduces words regarding direction on a map in VoiceThread. The target sentence structure “在… (used to describe the location)”. New words do not appear in isolation but have been integrated into the whole language context. Students can post a voice thread to practice their sentence structure through describing a location: not only watching the video but participating as active learners. At the end of each video, the instructor will encourage students to reflect the learning process and post questions in the LMS or through digital tools before the lab session.

Besides vocabulary and sentences structures, students should preview the new lesson with the guiding questions given in the assignment sheet. The pre-lab tasks often highly relate to the contents learned in VT. It functions as a check for understanding, helping students to apply the language knowledge in structured language use. Different from the language practice in the lab session, this part focuses more on controlled language practice, such as mechanical exercise. The checklist is posted on the announcement as a reminder to help students prepare for the lab session. It often includes the information of the pre-lab tasks due day, new language content learned in VT, questions will be discussed in the lab session, etc.

Synchronous session

The lab session is redesigned to increase the practice opportunities to help students participate more in meaningful tasks and communicational tasks.

Figure 8 illustrates the differences in time management between traditional lab sessions and the flipped ones. The traditional procedures, shown on the left-hand side, involve spending around 25 minutes on lecturing, which can be regarded as a waste of time, to the extent that students remain in a passive mode. Though the traditional teaching procedure allows 10 minutes for activities, this is insufficient for students to reach the higher-order thinking level as they start to remember and understand the new learning content.

In the flipped procedures, the first 10 minutes are devoted to reviewing and discussing questions about the previously studied material to check students’ understanding of the contents. Small quizzes may sometimes be given to motivate students to be well prepared for the lab. The instructor will analyze students’ answers and provide feedback immediately. The questions that posted by the students in VT or LMS will also be discussed. Instructors encourage every student to express their opinions and try to clear up misconceptions. By omitting the lecture component, the lab session gains 35 minutes for these other tasks. Students will participate in 2-3 activities during the practice time to produce output and interact with others. Tasks in the lab session often begin with simple, meaningful activities and follow with communicative activities that focus on the exchange of meaningful information. The last activity is often more complex, requiring students to use the target language as more as possible to achieve the lesson’s learning objectives.

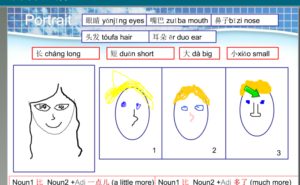

Figure 9 presents a drawing activity in the lab session. The topic of this lesson is to describe facial features and to use the comparative sentence to describe the difference. Students in the lab haven’t met each other in real life, so the instructor asks one of the students to be a teller, describing himself/herself by comparing with the portrait of the instructor (the picture on the left of the slide). In the description, new words and the sentences structures should be used along with other information. Other students use the drawing features in Adobe Connect to draw a portrait for him/her according to his/her description. The teller then tells other students which picture is more alike to himself/herself. As seen above, the new words and sentences structure do not appear in isolation but were designed into an integrated meaning-bearing task. Students learn to use the target language to express and exchange.

Review

The reading/visual-aural assignment focusses more on interpretive activity to have students read a paragraph or watched a video. Students will interpret and decode the text or video information first and answer multiple questions and open questions. The speaking & writing assignment involves interpersonal and presentational skills, which are designed for students’ language output practice. Students may engage in making an oral/written report, designing an itinerary, interviewing peers, expressing opinions, designing a project, etc. The design of the activity not only emphasize on the skills practice but also value the interaction among the online learning community. They may also join the topic discussion on Discussion Board in LMS or VT to present their ideas to the online community. Flipgrid, another online tool where students can post video comments together for discussion is also used as a speaking activity as they can interact with others by posting an audio/video feedback or respond by clicking “like” button. Padlet, which is an interactive digital wall is also adopted when needed, through which students can post their works and exchange ideas by making comments. At the end of each lesson, students will fill out a can-do list to check the mastery progress, as a way to help students reflecting and setting a goal for next learning circles.

<

Video 3. Course feedback (CI-MSU,2018)

The teachers and students are found to be positive toward this course format ((Li & Jiang, 2017; Li&Jiang, 2018). The 2+1+2 course format is proposed based on current online language learning environments and needs, with an intent to resolve the issues in the previous course delivery and to guide future design of online second language learning environment. However, more research needs to be done in revealing specific issues in the implementations to refine the design framework. Though the current format has touched upon on helping learners become more self-regulated, a systematic study of instructional strategies in promoting self-regulated online second language study is needed to carry this endeavor forward.

Acknowledgement

The book chapter is based on the research project conducted at the CI-MSU. The author would like to thank Dr. Jiahang Li at Confucius Institute at Michigan State University for providing support and suggestions in the working process.

Reference

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives. Retrieved from https://nsee.memberclicks.net/assets/docs/KnowledgeCenter/EnsuringQuality/BooksReports/146. a taxonomy for learning.pdf

Bonwell, C. ., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active Learning: creating excitement in the Classroom. ERIC Digest.

Chen, F. (2013). The comparison of two online Chinese teaching formats. Journal of Lanzhou Institute of Education, 29(12), 95–99.

CI-MSU (2014,6).CI-documentary 2014 [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7-roktkJH8w

CI-MSU (2018,1). Course feedback [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTUh7dGq6Yw

Colpaert, J. (2006). Pedagogy-driven design for online language teaching and learning. Source: CALICO Journal, 23(3), 477–497. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24156348

Dave Trupmie. (2016) . CI-MSU logo [photograph]. East Lansing. Retrieved from http://www.secondwavemedia.com/capitalgains/features/MSUconf1020.aspx

Henion, A., & Geary, N. (2008). Virtual China: online game teaches Chinese culture and language | MSUToday | Michigan State University. Retrieved April 30, 2018, from https://msutoday.msu.edu/news/2008/virtual-china-online-game-teaches-chinese-culture-and-language/

Jiang, Z., Zheng, B., & Li, J. (2016). How to best implement the flipped classroom in the online Chinese course? The 9th Teachnology Teaching and Chinese Language Teaching, Macao, China.

Laanpere, M., Pata, K., Normak, P., & Põldoja, H. (2012). Pedagogy-driven Design Of Digital Learning Ecosystems. Computer Science and Information Systems, 11(1), 419–442. https://doi.org/10.2298/CSIS121204015L

Lakin, J. (2008). Inter-player’s interaction [Online image]. Retrieved from http://blog.larkin.net.au/2008/07/28/multiplayer-browser-based-

Li, J., & Jiang, Z. (2017). Students’ perceptions about a flipped online Chinese language course. Journal of Technology and Chinese Language Teaching, 8(2). Retrieved from http://www.tclt.us/journal/2017v8n2/lijiang.pdf

Li, J., & Jiang, Z. (2018). Teacher’s perception about the effectiveness of an online flipped language course. The 29th annual conference of the Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education, Washington, D.C, U.S.

Li, J. (2018,Apr.10). Personal interview.

Li, Z. (2016,June.18). Personal interview.

Michigan State Board of Education. (2010). Michigan Merit Curriculum High School Graduation Requirements. Retrieved from http://www.chsd.us/highschool/curriculum/Michigan Merit Curriculum FAQ’s.pdf

Miller, M. R. (2016). MSU’s confucius institute leads in Chinese-language learning. Retrieved April 24, 2018, from http://www.secondwavemedia.com/capitalgains/features/MSUconf1020.aspx

Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based Language Teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Pearson. (2016). Teaching presence. Retrieved April 24, 2018, from https://www.pearsoned.com/wp-content/uploads/INSTR6230_TeachingPresence_WP_f.pdf

Radcliffe, D., Wilson, H., Powell, D., & Tibbetts, B. (2008). Designing next generation places of learning: collaboration at the pedagogy-space-technology nexus. Retrieved from http://www.uq.edu.au/nextgenerationlearningspace/

Sanborn, Rachel (2012). The Personal Impact of Online Chinese Learning [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTUh7dGq6Yw

Spino, L. A., & Trego, D. (2015). Strategies for flipping communicative language classes.

Starbucks coffee shop in ZON [Online image]. (2010). Retrieved from http://childrenstech.com/blog/archives/1462

Watson, J., Gemin, B., Ryan, J., Wicks, M., Fitzpatrick, J., Gillis, L., … Powell, A. (2009). Keeping pace with K-12 online learning: An Annual Review of State-Level Policy and Practice 2009. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED535909.pdf