Main Body

Chapter 12 – Potential Intersections of Learning Technology and General Aviation Training

Introduction

When you get on an airplane, odds are that you’re busy thinking about almost anything but the flight. Whether you’re mentally rehearsing for a big meeting at your destination, thinking about the fastest way to get to the beach when you land, or just trying to figure out the best way to keep your kids entertained for the next three hours. Very seldom does it cross the flying public’s mind to consider what type of training the pilots at the front of the airplane have received in the past and, what they’ll get in the future. Fortunately, we live in an era of unparalleled safety in regards to air transportation. In fact from 2009 to 2018, there has only been a single fatality on a domestic air carrier operating within the regulations of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) (Levin, 2018). In this time, over 9 million airline flights operated per year carrying upwards of 2.5 million passengers per day!

General Aviation (GA), essentially any flight not operated by an airline or the military, also enjoys a comparatively high safety record . However, it does not come close to comparing to the track record maintained by the country’s commercial air carriers. In 2016, the most recent year for which data is available, there were 17 separate accidents accounting for 29 fatalities in general aviation. Viewed through a different lens, for every 100,000 hours of time flown in GA aircraft there were .54 fatal accidents and .93 fatalities. While these numbers compare favorably with automobile transportation (37,461 fatalities in 2016) they still present a troubling reality that must be confronted.

In this chapter, we will examine the role that different types of training plays on aviation safety. What do the airlines do that general aviation does not, and how can we utilize new technologies to better imitate their methods and eventually, their success?

Current Pedagogies in the Federal Aviation Administration

Pilot training takes place through a variety of means determined by the specific type of flying that an individual will be completing. Many factors related to this training are decided by which set of regulations a pilot must adhere to. We will be examining the two broadest swaths of pilots; airline and general aviation. Airline pilots must adhere to Part 121 of the Federal Aviation Regulations; general aviation pilots have the option of completing their training under either Part 61 or 141 and then operating under Part 91. While the specific regulation numbers are not directly important to our conversation, a recognition that these pilots are operating under different rules does provide an important component of contextual information.

Airlines

Currently, training for airline pilots in the United States (and Europe) sets the gold standard for flight training. This training is accomplished under guidelines set forth by Part 121 of the Federal Aviation Regulations. It stipulates that pilots operating as the captain of aircraft on scheduled air service (airline flights) must complete a minimum of 20 hours of programmed initial training activities. Beyond this, they must also complete annual recurrent training of at least 25 hours of programmed training activities.

This training is typically accomplished through one of two primary providers. The first of these are internal training departments operated by the company. The second is by outsourcing the activities to a provider specializing in flight training. In either case, a similar methodology and set of technology is utilized to obtain the best results. To get a better idea of some of the technology utilized in this training, take some time to watch the video below which details the design process and capabilities of Flight Safety International’s training devices. These are on par with similar devices used by airlines around the United States.

https://youtu.be/xyx0p-ezPdg

(Flight Safety International FS1000).

This training utilizes a wide variety of technology before, during, and after the pilot’s training to maximize it’s effect.

General Aviation

While it is very easy to pinpoint what a typical training regime looks like for an airline pilot, it is much more difficult to do so for a a pilot operating in the general aviation (GA) category. In large part this is due to the sheer variety encompassed in this division of aviation. We briefly touched on this earlier in the chapter; now however, is a good opportunity to revisit it in order to both more fully explain it and to define the audience which this chapter hopes to impact.

Earlier, we mentioned that GA is essentially any flight not operated by an airline or the military. Some common examples of this are pilots who fly: recreationally, for personal business transportation, and those early in their training as they pursue a career that will eventually allow them to move into the air carrier (airline) category mentioned above. Beyond this there are hundreds, if not thousands of other reasons to fly that can be categorized as general aviation. For example, towing advertising banners above a sporting event, inspecting oil and natural gas pipelines, flight testing new types of aircraft, flying tourists on a sightseeing mission, or a taking a planeload of corporate executives to an important meeting in another city. GA aircraft also come in many varieties. From small two seaters, to large intercontinental jets more similar to the planes you might be used to flying in when you go on vacation. Beyond these though, flying a helicopter, glider, or even a hot air balloon is considered to be GA.

Because GA includes so many disciplines, it necessitates a much more complex system of rules to regulate training. This allows “weekend warrior” pilots to still pursue their hobby without necessitating training that would otherwise amount to tens of thousands of dollars on an annual basis while still maintaining an acceptable level of safety for those onboard the business jet flying to Paris to close an important merger. Because this system is so complex, we must narrow the focus of our examination to a much more specific group. In particular we will be focusing on the biggest group of these GA pilots who, are coincidentally also one of the most overlooked, and statistically most likely to be involved in an accident. These are the pilots who fly themselves and their families either for pleasure, business, or transportation, and those who are training towards a future career as a pilot. These pilots all fall under the rules of FAR Parts 61 & 91.

Per these regulations, the pilots we are discussing really only need to complete a training event once every 24 calendar months. This entails 1 hour of ground and 1 hour of flight instruction. Additionally, they must complete three take offs and three landings within the preceding 90 days in order to carry passengers. While these rules are much less stringent than their airline counterparts, a vast majority of pilots voluntarily gain as much, if not more experience in an instructional environment on an annual basis than an airline pilot would. Despite this, the accident rate for these flights remains much higher. In fact, according to the most recent Joseph T. Nall report (industry leading safety report), there were 991 non-commercial (GA) fixed wing aircraft accidents in 2014 compared to only 44 commercial fixed wing accidents in the same year (Kenny, D.J.).

With these statistics fresh in mind, we must ask: what are the differentiating factors between commercial and general aviation? While many are identifiable, two are much more prominent than others. These are the amount of experience a pilot has, and the training they have received. As there is no way to suddenly increase the number of hours a pilot has flown, we are left with a single option of increasing training quality to in turn, increase GA safety.

Potential Learning Tech Intersections

There is no shortage of dedicated instructors in general aviation. It truly is a passion career that attracts those who wish to hone their craft and be the best instructor that they can be. Often, the mitigating factor on an instructor’s success is the overall cost of flight training. The average cost to obtain the requisite training toward a private pilot’s certificate easily eclipses $10,000. By any measure this is an expensive hobby so, those pursuing it often don’t have the means to pay for additional practice time in the airplane or, review time with their instructor. This has led to an unfortunate focus on simply getting students out the door, license in hand, at the lowest cost possible. This culture has become cemented over many generations and it will require a massive paradigm shift to change.

While this change is undoubtedly necessary, it will take time to affect. In the meantime, perhaps we can utilize new technologies to increase training opportunities without also drastically increasing costs as well. In the remainder of this chapter, we will explore several potential applications of technology that hold potential to achieve this goal.

Of note, in most cases, it will be necessary for a public GA organization to take the lead on implementing these projects. This will allow for a distribution of costs across a large body of students. Additionally, these groups have the potential to recoup the implementation expenses by providing the coursework as a benefit to their paying members.

Computer based prep work

Computer based coursework in the form of a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) holds a great deal of promise for the aviation industry. In most industries/subjects, these courses are typically provided at a nominal, if not free of charge, cost. There are many arguments agains MOOC’s and their efficacy however, most of these arguments can be negated through the proper application of these courses.

In flight training, and GA as a whole, it should be very possible to assign MOOC’s or individual modules to a student as a form of pre-lesson homework. This will allow a student to arrive at the airport for a one on one lesson with their instructor with a higher level of knowledge than they would otherwise have had. In turn, this will allow the instructor to move more quickly to a discussion of advanced concepts that may not be suitable for the MOOC format and it’s limitations

Interactive Diagrams (3D Modeling)

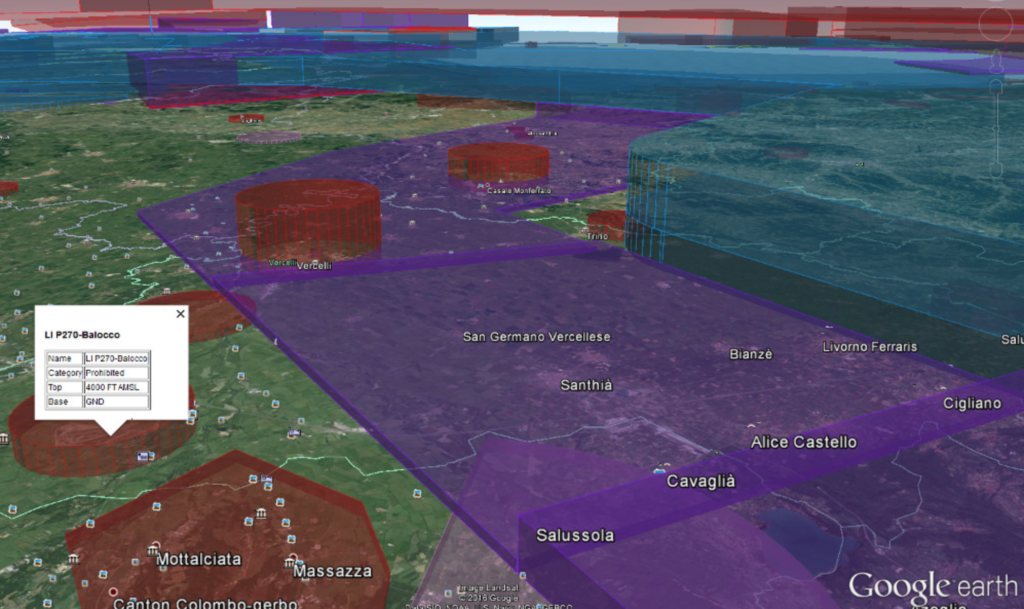

Many of the concepts that pilots must grasp can be rather abstract. This is particularly true when it comes to things such as visualizing certain training maneuvers, or recognizing where an area of restricted airspace begins and ends. To help correct for these deficiencies, applying 3D Modeling software for scenario based training could be a great asset. This tool coupled with interactive quizzing or, application of game learning theory can drastically increase the FAA’s current approved methodology of teaching these concepts which consist primarily of readings and still charts. In particular the concept of adaptivity in game based learning is intriguing. In their article Foundations of Game Based Learning, the authors state that this medium allows for a great deal of personalization based on an individual learner or situation (Plass, 261). This adaptivity is of particular importance to pilots who will seldom face an identical situation. Instead, they may face many similar situations with small, but important, details that will require them to adapt existing knowledge and experience literally on the fly.

The beginning phases of adopting this technology to aviation flight training has already begun. For example, Alus, an IT company has started to map airspace inside of Google Earth, see figure below. (Realis-Luc, A.). Unfortunately, making this software work currently requires a moderate to high level of programing and file management ability. This puts it outside of the reach of most GA pilots. However, the promise is huge.

(Realis-Luc, A.).

Flight Simulation Technology

Much in the same way that 3D modeling combined with interactive quizzing will allow students practice in adapting their learned skills, flight simulation technology can meet the same needs. By utilizing simulator technology, pilots in training are able to experience scenarios that push the limits of their abilities without ever experiencing true danger to themselves or, their passengers. This allows for another concept of game learning theory, that of graceful failure. This component of the theory states

“Rather than describing it as an undesirable outcome, failure is by design an expected and sometimes even necessary step in the learning process. The lowered consequences of failure in games encourage risk taking, trying new things, and exploration. They also provide opportunities for self-regulated learning during play, where the player executes strategies of goal setting, monitoring of goal achievement, and assessment of the effectiveness of the strategies used to achieve the intended goal (Plass, 261).”

While simulator usage is expensive, often equalling the cost per hour of operating a real aircraft, the benefits afforded by the ability to safely fail and to simulate multiple simultaneous failures provides airline pilots with a real edge that, GA pilots seldom receive from their training.

Live Online Learning

Finally, we should examine the potential of large class size synchronous courses or webinars provided by industry leading training providers. An example of this would be courses currently offered by companies like Flight Safety International (FSI) who we have already discussed. FSI offers online classrooms for their corporate and airline clientele where they bring substantial multimedia resources to bear such as 3D modeling, simulation, and modern design services. These programs are tailored to the needs of clientele operating multi million dollar jet aircraft, not those in much more humble propellor driven aircraft. With that consideration, they are priced commensurately in a range from $180 to $2,430 (Courses (n.d)). This represents a significant expenditure that places resources such as these outside of the reach of most GA pilots.

If a public organization with a vested interest in general aviation safety, such as the Experimental Aircraft Association or Aircraft Owner and Pilot’s Association, were to offer courses that emulate these and that also meet the needs of a wider audience like their membership, they could bring economies of scale to the equation lowering the overall cost per pilot to a much more reasonable level.

Conclusions

While aviation as a whole is an incredibly safe means of transportation, there is a definitive need for changes to training within General Aviation. By modernizing training practices from those which are primarily lecture, and text based to those of a more recent vintage which utilize multimedia resources and principles; we as aviation professionals can emulate the extremely successful training regimens provided by airlines. In the past, this has been extremely difficult to do because of the significant costs associated with their practices. As learning technology has become more widely available though, it has also provided more reasonable priced alternatives which can be exploited in the interest of increasing safety.

Citations

Air Traffic By The Numbers. (2017, November 14). Retrieved April 20, 2018, from https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/by_the_numbers/

Courses. (n.d.). Retrieved April 22, 2018, from https://elearning.flightsafety.com/livelearning.html

Fact Sheet – General Aviation Safety. (2014, September 19). Retrieved April 18, 2018, from https://www.faa.gov/news/fact_sheets/news_story.cfm?newsId=21274

Flight Safety International FS1000 Full Flight Simulator. (2016, June 01). Retrieved April 18, 2018, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xyx0p-ezPdg

Kenny, D. J., & Smith, M. (n.d.). Joseph T. Nall Report(Rep. No. 26th) (B. Knill & A. Sable, Eds.). Richard G. McSpaden Jr.

Levin, A. (2018, April 17). Death on Southwest Plane Shatters Record U.S. Safety String. Retrieved April 18, 2018, from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-04-17/death-on-southwest-plane-shatters-unprecedented-safety-string

NHTSA. (2018, April 12). USDOT Releases 2016 Fatal Traffic Crash Data. Retrieved April 18, 2018, from https://www.nhtsa.gov/press-releases/usdot-releases-2016-fatal-traffic-crash-data

Plass, J. L., Homer, B. D., & Kinzer, C. K. (2015). Foundations of Game Based Learning. Educational Psychologist,50(4), 258-283. Retrieved April 22, 2018, from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1090277.pdf.

Realis-Luc, A. (2018, January 01). AirspaceConverter. Retrieved April 19, 2018, from http://www.alus.it/AirspaceConverter/