Main Body

Chapter 2: The Impact of Twitter on Participation, Collaboration, and Problem Solving in Higher Education Classes by Joanne Baltazar Vakil

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Twitter_Logo_Mini.svg

Higher Education Classes, whether conducted in MOOCs, credentialed online course offerings, or even face-to-face, may gradually see the rise in the use of Twitter in classroom discussions. This chapter will explore the impact of using Twitter in higher education for math problem solving on a student’s sense of participation and collaboration in a STEM class through the participation metaphor (Sfard, 1998) while learning in a STEM community (Brown, Collins & Duguid, 1989, Lave & Wenger, 1991), as well as for the creation of knowledge (Hakkarainen, Paavola, Kangas, & Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, 2013). This chapter will also take a careful look at the potential of how mathematical problem solving can be facilitated by using Twitter. Topics addressed will include characteristics of instructors who use Twitter in the classroom, current research on the use of Twitter in higher education, and survey results of students who have participated in higher education coursework requiring Twitter for class discussions.

Instructors implementing Twitter in the classroom have been characterized as “reform minded, open to change, and interested in restructuring their local communities environment to include web-based and social media tools” (Forte, Humphreys, & Park, 2012). In an investigation of higher education faculty, Veletsianos (2012) found that research on the use of Twitter and other social network sites remains unexplored. Roblyer et al. (2010) found that “’traditional’ technologies, such as e-mail” were still preferred. A number of themes were found in scholar’s Twitter practices and activities. These include information, resource, and media sharing, expanded learning opportunities, requesting assistance and offering suggestions, living social public lives, digital identity and impression management, connecting and networking, and presence across multiple online social networks (Veletsianos, 2012).

Despite the findings that Twitter remains unexplored, a study by Kassens-Noor (2012) reports that using “Twitter is a powerful tool in applying and creating ideas” in a 24/7 communication platform (p. 19) and that when comparing a Twitter group with students writing traditional diary entries and meeting once for a group discussion, Twitter group students performed better with knowledge creation as it “facilitates sharing of ideas beyond the classroom via an online platform that allows readily available access at random times to continue such discussion” (Kassens-Noor, 2012, p. 19).

In addition to facilitating the sharing of ideas, Twitter has the potential to promote student engagement. In a study investigating 125 undergraduates, Junco, Heiberger, & Loken (2011) conducted a survey and content analysis of class Twitter exchanges and found “experimental evidence that Twitter can be used as an educational tool to help engage students and to mobilize faculty into a more active and participatory role” (p. 119). Engagement was also found to increase in an urban community college where students tweeting for an online course self-reported an increased level of engagement, as well as a higher final grade average (Hirsh, 2012).

A number of resources have been published detailing practices in implementing Twitter in universities and academia. Mollett, Moran, & Dunleavy (2011) highlight their work “as a resource for research, teaching and impact activities.” The group provides a handbook that offers definitions and step-by-step directions in setting up an account, building up followers, and using Twitter for research projects and teaching.

This chapter section features survey and interview responses from students who have had to participate in discussions using Twitter and compare these experiences with face to face classroom discussions. The data sources comes from a short Google Form survey assessing student familiarity, ease, access, and perceptions of Twitter as a tool for discussions.

This study identified seven students who, within the past year, participated in a higher education course that required the use of Twitter for class discussions. The Google Form consisted of eight brief questions which were emailed to the students via a link to participate in the survey.

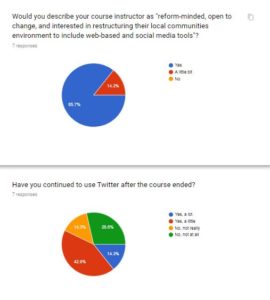

Aligned with Forte, Humphreys, & Park’s (2012) research, a great majority of the students, 85.7% found their course instructor to be “reform-minded” and “open to change.” With most of the participants enrolled in a teacher education program, results were a little bit lower, 42.9%, with the response, “Yes, a little” as to whether the student would continue to use Twitter after the course ended. 28.6% of the respondents claimed that they would “not at all” use Twitter after the course ended.

With the focus of this study targeted on the creation of ideas and knowledge (Hakkarainen et al., 2013), survey results indicated that a little over half of the respondents felt “yes, a little” that tweeting for weekly discussions helped create ideas among them and their classmates. A few of the respondents, 28.6%, answered “No, not really.” One participant, a freshman taking a college level Algebra course, explained that though she and her classmates tweeted regularly for the class, the content mainly comprised of questions such as, “How do you do #7?” Providing homework hints or answers may not necessarily be an ideal example in demonstrating the potential for Twitter to foster group knowledge discussion.

Only 28.6% of the respondents actually solved math problems through the use of Twitter, with 42.9% explicitly not having solved math problems with that particular forum. More than half felt that Twitter works better than a traditional text-based discussion board. Overall, students were able to access and navigate the platform, with 42.9% taking only a week or less to feel comfortable with Twitter. Despite the ease and knowledge creation within the discussion group, however, a great majority of those surveyed, 85.7% answered that if in the future they were to teach a course, they would not (“not really” or “not at all”) incorporate Twitter into required weekly discussions.

Further investigation of this study would reach out to more survey participants. A more thorough qualitative analysis through an open-ended survey question or video-recorded interview would seek to identify reasons behind why respondents would be reluctant in using Twitter in their future classrooms.

Brown, J.S., Collins, Al, & Duiguid, P. (1989) Situated cognition and culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18, 32-42.

Forte, A, Humphreys, M., & Park, T. (2012). Grassroots professional development: How teachers use Twitter, presented at the Sixth International AAAI Conference on weblogs and Social media, Dublin, Ireland: Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence.

Hakkarainen, K., Paavola, S., Kangas, K., & Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P. (2013). Sociocultural perspectives on collaborative learning: Toward collaborative knowledge creation. In C.E. Hmelo-Silver, et al. (Ed.), The International Handbook of Collaborative learning (pp. 57- 73). New York: Routledge.

Hirsh, O. S. (2012, January 1). The Relationship of Twitter Use to Students’ Engagement and Academic Performance in Online Classes at an Urban Community College. ProQuest LLC,

Junco, R., Heiberger, G., & Loken, E. (2011). The effect of Twitter on college student engagement and grades. Journal of

Computer Assisted Learning, 27(2), 119-132. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2729.2010.00387.X

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Mollett, A. Moran, D., & Dunleavy, P. (2011). Using Twitter in university research, teaching and impact activities. Impact of social sciences: maximizing the impact of academic research, LSE Public Policy Group, London School of Economics and Political Science., London, UK.

Kassens-Noor, E. (2012). Twitter as a teaching practice to enhance active and informal learning in higher education: The case of sustainable tweets. Active Learning Higher Education, 13, 9–21.

Roblyer M.D., McDaniel M., Webb M., Herman J. & Witty J.V. (2010) Findings on Facebook in higher education: a comparison of college faculty and student uses and perceptions of social networking sites. The Internet and Higher Education, 13, 134–140.

Sfard, A. (1998) On two metaphors for learning and the dangers of choosing just one. Education Researcher, 4-13.

Veletsianos, G. (2012). Higher Education Scholar’s Participation and Practices on Twitter. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 28(4), 336- 349.