Main Body

Chapter 6 – Evolution of Student Response Systems in the College of Nursing at OSU by Barbara Price

Evolution of Student Response Systems in the College of Nursing at OSU

The College of Nursing is pursuing deeper learning for students by incorporating Student Response Systems (SRS) to improve the education of nursing majors in the BSN program. SRS, flipped classrooms, bring your own device, and digital literacy are current trends in higher education to improve student engagement and active learning. The use of SRS learning technology has evolved in the College of Nursing over the past decade. How have student response systems impacted teaching and learning in the College of Nursing? Are students more engaged with active learning and are SRS’s fostering deeper learning? Read this chapter to find the answers to these questions.

What is a Student Response System (SRS)?

A SRS is a combination of hardware and software that allow instructors to collect immediate feedback from students in a classroom setting. Students respond to instructor questions using remote devices such as clickers, cell phones or laptops. Instructors view the aggregated student data from the responses in real time allowing them see how well students are comprehending the material. They can adapt their instruction and make adjustments to better meet student needs. SRS can be used for taking attendance, taking surveys, and quizzing students. Watch the short video below for a quick overview of SRS.

Why use SRS?

Research from a 2015 statistical analysis (Hooker, Denker, Summers, & Parker, 2016) demonstrated the benefits of using SRS in large lecture classrooms. This research showed that SRS can overcome barriers to class participation which is especially challenging in large lectures. Some barriers to class participation are communication apprehension and student personality traits. For example, some students fear embarrassment and making mistakes in public in larger classes. SRS can overcome these barriers because students interact anonymously with their instructors. Another barrier to class participation in large classes is logistics. Instructors simply don’t have time to interact individually with each student. Usually only a few students are able or willing to respond to instructor questions. However, with SRS each student has the opportunity to interact with their instructor overcoming the logistics barrier.

Research has shown that students who participate in class tend to receive higher grades (Rocca, 2010). This is likely a result of students being more engaged in their learning when they interact with instructors. Students who are answering questions demonstrate performance cognitive learning (Bruff, 2009). Even though students may not consider this to be direct dialogue with their instructor, they are providing formative feedback that their instructor would not receive otherwise. This also improves teaching and learning.

Another benefit of using SRS is that they allow instructors to gather a large amount of formative feedback quickly. According to Chan, Tam and Li (2011) ‘Timely and high-quality feedback is the underlying milestone of formative assessment in promoting student individual responsibility for their own learning and thus fostering deep learning.’ (p. 326). Asking review questions using SRS may provide more accurate and honest reflection of student learning allowing instructors to adapt their instruction to best meet student needs.

Students report the use of SRS provides a more enjoyable learning environment (Ioannou & Artino, 2010; Stowell & Nelson, 2007). Students like to receive feedback on how well they understand course material, they like to see how they are doing compared to their peers, they enjoy the interactivity and they have an increased perception of active learning (Barnett, 2006; FitzPatrick, Finn, & Campisi, 2011; Ioauuou & Artino, 2010). Additional research again indicates that students engaged in active learning retain more information than they do in a traditional lecture (Prince, 2004). These are significant benefits of SRS from the student point of view.

More Reasons to Use SRS

Research from Hunsu, Adesope, & Bayly (2016) confirmed the benefits of using SRS mentioned above. They reported, “With the use of clicker-based technologies however, students are able to gauge their responses against those of other classmates, which may improve their self-confidence and perhaps spur them to diligence” (Knight & Wood, 20015). This additional benefit of increasing student confidence is another reason to use SRS.

Another feature of SRS is that instructors can use it in lectures to record class attendance. Taking class attendance often results in improved class attendance, especially when linked to grades. This also improves learning.

Studies show student attention and recall diminish after 20 minutes of lecture time (Burns, 1985). Instructors can use SRS to break up a lecture with questions that trigger discussions. This discussion break gives students the opportunity to refocus on the lecture, possibly fostering increased participation and sustained learning engagement, peer discussions and gives instructors a chance to provide immediate feedback on group discussions (Zhu, 2008). Many lecturers also prefer to break up their lectures rather than speaking throughout for an hour or more through the entire lecture.

Instructors in large lectures often tend to interact with students in the front rows while students in the rows further back are pursuing non-class related activities. This type of learning environment leaves many students disengaged with course material presented in class (Mayer et al., 2009). SRS are appealing because they engages these students who would otherwise not be paying attention to the instructor.

SRS questions may provide important learning strategies for gauging student comprehension, uncovering misconceptions, and monitoring conceptual change in students about the subject matter (Caldwell, 2007; Lin, Liu, & Chu, 2011). As instructors become aware of their students’ level of understanding, they can address areas that students are struggling with the most (Anderson, Healy, Kole, & Bourne, 2011, 2013). Instructors can also spend more time to re-teaching challenging concepts in more creative ways while spending less time teaching concepts that students already understand (Kay & LeSage, 2009).

There are studies that report both students and instructors like using SRS. Many believe an SRS positively impact different cognitive and affective learning outcomes (Beatty et al., 2006; Caldwell, 2007). Studies have compared student instruction using SRS with student instruction not using SRS on different cognitive measures such as short-term and long-term retention, measures of learning transfer, and end-of-course achievement outcomes. A number of these studies showed using SRS facilitated student achievement and some showed a positive association with student grades on final exams (Morling, McAuliffe, Cohen, & DiLorenzo, 2008; Poirier & Feldman, 2007; Uhari, Renko, & Soini, 2003).

Actively engaging in classroom learning activities is a precursor to meaningful learning. Getting involved in class improves knowledge acquisition and retention across all educational levels (Conrad & Donaldson, 2004; De Gagne, 2011). Active engagement and participation encompasses all academic and non-academic aspects of a student’s learning experience (Krause & Coates, 2008). Additional studies (Riggs & Gholar, 2009, and Ryan & Deci, 2000) showed students who are engaged in class show a great commitment to tasks, are more attentive, are intrinsically motivated, put in more effort and are emotionally invested in learning. Studies by Chen, Gonyea, & Kuh, 2008, Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005, and Tinto, 1993 showed student engagement has been positively connected with desirable learning outcomes such as perseverance, retention, satisfaction, academic performance, and higher graduation rates. Since SRS facilitate student engagement which is so important to learning, many instructors are adopting it to increase student motivation for class attendance and involvement in student activities (Cain et al., 2009; FitzPatrick et al., 2011). SRS may even foster engagement with learning material that could result in higher levels of conceptual learning (Hake, 1998).

Has the College of Nursing Embraced SRS?

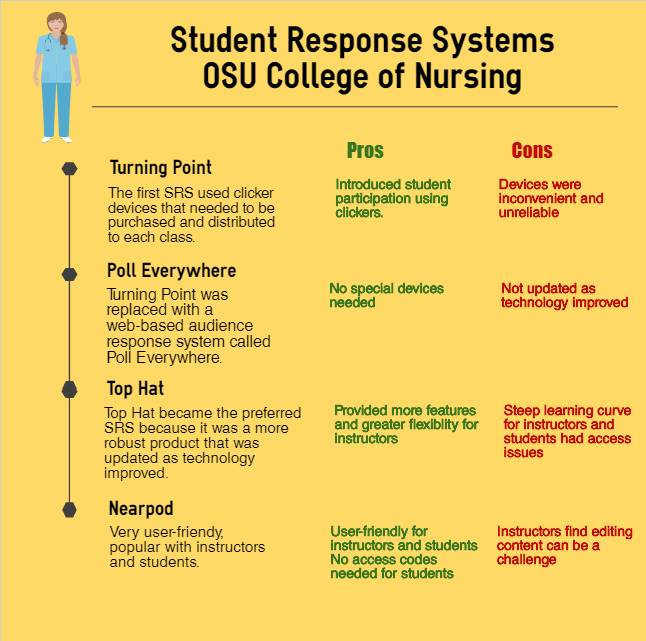

Turning Point

A little over a decade ago the first SRS, Turning Point, was used in the College of Nursing. Turning Point was a SRS that used a hardware-software polling system with dedicated handheld devices called clickers and receivers. These clickers looked similar to a TV remote control and worked by the same principle. Instructors using Turning Point projected multiple choice questions on overhead screens during their lectures and students were asked to respond by clicking the corresponding button on their clicker. Responses were tallied by the software and aggregates of the responses were displayed as charts. Students could be given the opportunity to work in groups to discuss their rationale for the answers they gave. Instructors provided appropriate feedback to students. This response system allowed instructors to monitor student understanding and identify student misconceptions about the lecture content. Because students could respond anonymously they were more inclined to participate than when asked to raise their hands in class. Some of the benefits of Turning Point were the anonymous polling with results that displayed immediately, improvement in student attentiveness, the ability to track individual responses and the ability to gather data for analysis and reporting. Unfortunately, one of the big drawbacks to Turning Point was that the clickers needed to be purchased and distributed to students. They were cumbersome to maintain and keep track of. Eventually they became obsolete. Turning Point is no longer used in the College of Nursing.

Poll Everywhere

About 5 years after Turning Point was introduced, Poll Everywhere became the preferred SRS for classroom use because it didn’t require any additional devices (like clickers) and it was easier to use. Poll Everywhere is a web-based SRS that lets instructors embed interactive activities into their lessons. Students can respond to polls online or via SMS texting on their phones which eliminates the need for clickers. Instructors can use multiple poll types in their classes to identify gaps in understanding. Because the polling is anonymous it creates a safe space for shy and reluctant students to respond. Instructors benefit because they hear from the entire class simultaneously. Poll Everywhere is free to use. It provides the same benefits and features that Turning Point offered. Faculty also use Poll Everywhere for presentations outside OSU. The version of Poll Everywhere used in the College of Nursing limits the number of students in a class who can use it. The free version of Poll Everywhere is still available for use but is not being widely used in the College of Nursing.

Top Hat

Top Hat has been used in the College of Nursing for several years. It is more robust than Turning Point or Poll Everywhere. Top Hat is free to use. It is updated as new technology becomes available. It has more features and provides more flexibility for the faculty using it. It is integrated with Carmen LMS. However, it has a steep learning curve for faculty. Students need to log into Top Hat using their OSU credentials leading to accessibility issues for some students. Top Hat is used in classes to for presentations and surveys where students provide feedback and opinions. It’s also used for self-assessment and attendance.

Top Hat is used to leverage student devices to stimulate discussion, identify misconceptions and to get student feedback in real-time. One of the benefits of Top Hat is that it motivates students to participate in class by creating an engaged learning environment. Every student can participate freely whether sitting in the front row or back row of any classroom, even large lectures. Since students participate anonymously they are comfortable sharing their thoughts, even with sensitive subject matter. Discussion prompts can be embedded between slides to prompt student dialogue allowing instructors to check for comprehension or award participation points. Students can use interactive features to vote their responses helping instructors identify misconceptions. Top Hat provides a flexible response option that allows students to respond with a drawing. Top Hat can also be used for attendance to automatically verify if a student is physically present in class and assign grades for participation and attendance when students sign in on their devices using a unique code.

Students can sync their devices with the lecture slides and follow along in real time. This means students can’t move ahead of their instructor so their attention remains focused on what is being presented. Instructors can share student responses and correct answers using visual graphs, heat maps and word clouds. Students can download, study and review lecture slides after the lecture at any time by using the review mode. Instructors can upload their slides into TopHat and organize them. They can also embed interactive polling questions between slides to create a seamless presentation. Various interactive questions types are available including multiple choice, word answer, numeric answer, fill-in-the-blank, matching, click-on-target, and sorting.

Top Hat is still available for use in the College of Nursing.

Nearpod

Nearpod was introduced in the College of Nursing in January 2017. Nearpod is a cloud-based application that allows instructors to create presentations with options to shift from lecture to individual or group activities. It can be used self-paced or as a live lesson. It integrates with the Canvas LMS to link a presentation in real-time with activities such as poll questions, fill-in-the-blank questions, open-ended questions, quizzes, memory test activities or the Draw It tool. It works well for flipped classrooms. PINS allow users to view presentations from any device, anytime. Nearpod has all the benefits of Top Hat but it is more user-friendly than Top Hat. It has additional features that allow it to be used for collaborative activities in class.

Nearpod allows instructors to create interactive lessons by importing lessons such as pdfs, jpegs and ppts. Interactive features like Virtual Field Trips, 3D Objects, Quizzes, Polls, and Open Ended Questions can also be included. There are also thousands of free or paid lessons from educators that can be downloaded. These lessons can be customized to fit student needs. Lessons can be synchronized and controlled across all student devices. Instructors can evaluate student responses live or use reports post-session by viewing student answers individually or as a class. Nearpod enables 100% active participation in every lesson thus creating an inclusive and immersive learning experience. Nearpod creates an inclusive and immersive learning experience by allowing students to actively participate in every lesson and take ownership of their education.

Nearpod is popular with instructors and students in the College of Nursing and is currently the preferred SRS. View the video below to see a demonstration of how Nearpod works.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ThlqFu1qIlM&t

Does Nearpod Promote Deeper Learning?

SRS do have an impact on active learning. SRS also increased student awareness of their level of understanding compared to their classmates (Efstathiou and Bailey, 2012). A recent study by McClean and Crowe (2016) found all 63 university students who were surveyed agreed that Nearpod was easy to use and were happy to use their own device during class. All of the students reported they believed they learned more using Nearpod than from a traditional lecture format. Most students said that Nearpod was engaging and they would like to use it again.

What do College of Nursing Instructors Think About Nearpod?

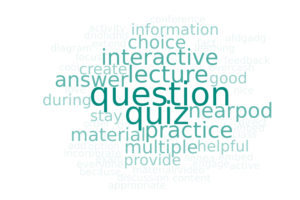

I interviewed four College of Nursing clinical faculty in March 2018. All four faculty members teach undergraduate clinical nursing courses with large lectures and have used Nearpod for at least one or two semesters. Instructors primarily use Nearpod in their lectures for presentations with case studies, questions and quizzes. They are using it for their flipped classrooms. Some instructors also use the self-guided presentations. Three instructors use Nearpod for attendance for at least one or more classes during the semester. They confirmed the results of the research that showed student engagement increased with the use of Nearpod. They also confirmed an increased ability to gauge student comprehension and misunderstandings which allowed them to adapt their teaching to address student needs. They like the immediate feedback which shows if students are grasping the course content. One instructor stated that Nearpod has added a refreshing dimension to her teaching. Another instructor felt the interactive piece of Nearpod was the highlight. Another likes Nearpod because it allows videos to be added to lessons and the transition from question to video is an easy transition. Instructors like to use Nearpod for quizzing students, especially when used with Carmen LMS so they can see student names. One instructor reported that guest speakers also like using Nearpod. All instructors agreed that it was easy for them to incorporate Nearpod into their lesson preparation and easy to use in their classrooms. They also reported it was easy for students to use Nearpod because they don’t need to log in with a user name. They just log in with a code and get started. One instructor stated that Nearpod is good technology. All agreed there have been minimal technical issues. Instructors agreed that students seem to like Nearpod too. Instructors shared that because Nearpod allows students to give answers without intimidation there is more class participation. An instructor stated that most students will not raise their hands in class so Nearpod is really beneficial to get their feedback. All four instructors stated that they plan to continue using Nearpod in future classes and would recommend it to other faculty.

However, no learning technology is perfect and there were a few ways that instructors felt Nearpod could be improved. There is still not 100% class participation even with Nearpod. One instructor estimated that typically about two-thirds of her class uses Nearpod when given the opportunity. Some students are not thrilled with the notes feature in Nearpod. It’s hard for students to take notes because they don’t have Power Point slide availability. Nearpod is not as user friendly as typing in notes section of Power Point slide. Another issue is that students can’t save the entire session. From the instructor’s perspective, it can be cumbersome to make changes to presentations because slides cannot be edited once they are in a presentation. An instructor reported that there is no functionality in each slide that is uploaded as a pdf so hyperlinks do not work. She would recommend changing that. Another instructor would like to be able to keep the student’s specific responses. None of the instructors use Nearpod in all their lectures. One instructor mentioned that she doesn’t use it in all her lectures because students get burned out on it when it is over-used. One instructor uses Nearpod more for reviews and in class activities rather than for an entire lecture due to limitations of note-taking feature. One of the instructors plans to change how she will use Nearpod next year preferring to have students work in small groups to do case studies on their own and then have them come back as a group to answer questions. There has been an occasional technical issue sharing student responses where the student responses were shown to the instructors by not shown to the students. But this was considered to be a minor issue.

Nursing Faculty Quotes

“I’m more cognizant of the types of questions I ask. What may have been a multiple choice question I have turned to a collaborative question so all students can contribute.” Anita Zehala, Clinical Instructor

“I like the immediate feedback. It shows me if they’re grasping content. Really helpful in health assessment when they’re brand new because they’re not as interactive and not comfortable asking questions.” Hollie Moots, Clinical Instructor

“It’s a good way to get students to interact. It helps class be more student-focused. I use it for application. It’s great for figuring out that higher level thinking.” Jill Volkerding, Clinical Instructor

“Nearpod allows for student engagement without intimidation so even shy students interact….Something that pops out can open another conversation with the class or additional comments from the instructor.” Janice Wilcox, Clinical Instructor

What do College of Nursing Students Think About Nearpod?

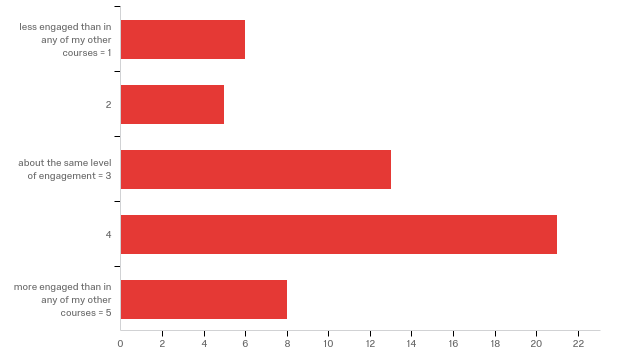

A Qualtrics survey was given to students in the College of Nursing at the end of spring semester 2017. Approximately fifty students responded to the survey. The responses to the question “How Engaged Were You?” are shown in the chart below. These results show the majority of students indicated they were more engaged in courses using Nearpod than in their other courses. This confirms research showing that SRS improve student engagement.

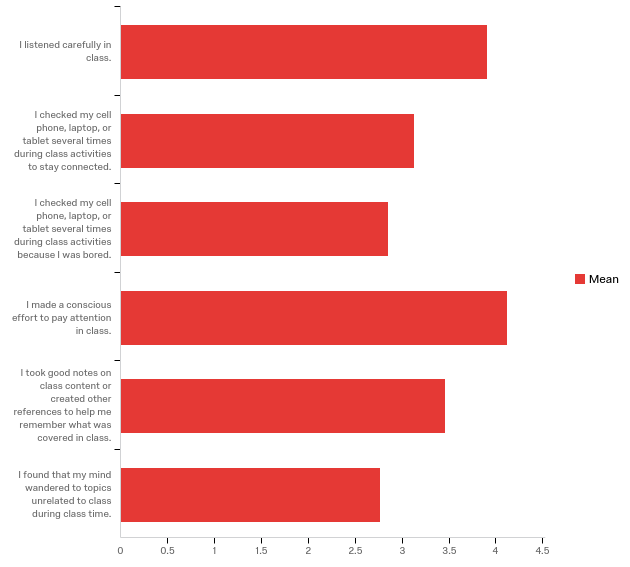

The survey included additional questions to ascertain student engagement. Students responded to these questions on a 5 point Likert scale. The results shown below reveal that the mean response to the questions “I listened carefully in class” and “I made a conscious effort to pay attention in class” were both at a mean score of 4 which indicates Nearpod has a positive impact on active listening and student engagement. The chart also shows that the questions “I checked my cell phone, laptop, or table several times because I was bored” and “I found that my mind wandered to topics unrelated to class during class time” received a mean score of about 2.5 which is a positive result because lower score is for indicators that do not reflect student engagement in class.

The reports of the instructors that students like using Nearpod the willingness of students to participate using Nearpod compared to raising their hands in class is a good indication of the effectiveness of Nearpod. The increased dialogue in large lectures and the ability for Nearpod to be used with small group activities in large lectures is also an indication of it’s effectiveness. Although more research is needed to determine how much impact Nearpod is having on student engagement, Nearpod does seem to be having a positive impact on student engagement and student learning in the College of Nursing. To collect more in-depth student information on the impact of Nearpod on student engagement I would recommend student interviews and additional surveys.

What is the Future of SRS at the College of Nursing?

Nearpod has been found to be effective in engaging students in active learning and it is popular with students and instructors so it has a promising future. It is being updated as new technology becomes available so it has potential to last longer than Turning Point. Nearpod is user-friendly so I believe it will continue to be more widely used than Poll Everywhere or Top Hat. However new artificial intelligence technology may introduce more sophisticated methods of engaging students in the classroom and may lead to new learning technology that could eventually replace Nearpod. Regardless of the future of Nearpod, I believe the College of Nursing will continue to use SRS to engage students and foster deeper student learning.

References

Anderson, L. S., Healy, A. F., Kole, J. A., Bourne Jr., L. E. (2013). The clicker technique: cultivating efficient teaching and successful learning. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 27 (2)(2013), pp.222-234.

Barnett, J. (2006). Implementation of personal response units in very large lecture clases: Student perceptions. Australasian Journal of educational Technology, 22, 474-494.

Beatty, I. D., Gerace, W. J., Leornard, W. J., Dufresne, R.J. (2006). Designing effective questions for classroom response system teaching . American Journal of Physics, 74 (1)(2006), pp. 31-39.

Bruff, D. (2009). Teaching with classroom response systems: Creating active learning environments. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Burns (1985). Information impact and factors affecting recall. Paper presented at Annual National Conference on Teaching Excellence and Conference of Administrators, Austin, TX (1985, May).

Cain, J., Black, E.P., Rohr, J. (2009). An audience response system strategy to improve student motivation, attention, and feedback. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 73 (2)(2009), pp. 1-7.

Caldwell, J.E. (2007). Clickers in the large classroom: current research and best-practice tips. Life Sciences Education, 6 (1) (2007) , 9-21.

Chan, C.K. Y., Tam, V.W. L., & Li, C. Y. V. (2011). A comparison of MCQ assessment delivery methods for student engagement and interaction used as an in-class formative assessment. International Journal of Electrical Engineering Education, 48, 323-337.

Chen, P.D., Gonyea, r., & Kuh, G. (2008). learning at a distance; engage or not. Journal of Online Education, 4 (3)(2008).

Clickers image, (April 8, 2018), retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/unav/4464311633

Conrad, R.M., Donaldson, J.A., (2004). Engaging the online learning: Activities and resources for creative instruction. John Wiley & Sons, Sam Francisco, CA (2004).

DeGagne, J.C., (2011). The impact of clickers in nursing education: a review of literature. Nurse Education Today, 31 (2011`), p. 34-40.

Efstathiou, N. & Bailey, C. (2012). Promoting active learning using Audience Response System in large bioscience classes. Nurse Educ Today, 32:91-5.

Fitzpatrick, K.A., Finn, K. E., & Campisi, J. (2011). Effect of personal personal response systems on student perception and academic performance in courses in a health sciences curriculum. Advances in Physiological Education, 35, 280-289.

Hooker, J. F., Denker, K. J., Summers, M. E., & Parker, M. (April 01, 2016). The development and validation of the student response system benefit scale. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 32, 2, 120-127.

Humber College Centre for Teaching and Learning, (Mar 16, 2017), video retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QuEdP53XtUk

Hunsu, N. J., Adesope, O., & Bayly, D. J. (March 01, 2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of audience response systems (clicker-based technologies) on cognition and affect. Computers & Education, 94, 102-119.

Ioannou, A., & Artino, A. R. (2010). Using a classroom response system to support active learning in an education psychology course: A case study. International of Instructional Media, 37, 315-325.

Lecture image, (April 8, 2018), retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/eb/UCT_Leslie_Social_Science_lecture_theatre_class.JPG

Kay, R.H., & Lesage, A. (2009). Examining the benefits and challenges of using audience response systems: a review of the literature. Computer & Education, 53 (3)(2009), pp. 819-827.

Knight and Wood (2005). Teaching more by lectureing less. Cell Biology Education, 298-310.

Krause, K. & Coates, H. (2008). Students’ engagement in first-year university. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(5)(2008), pp. 493-505.

Mayer, A., Stull, K., DeLeeuw, K., Almeroth, B., Bimber, D., Chun , et al. (2009). Clickers in college classroom: Fostering learning with questioning methods in large lecture classes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34 (1)(2009), 51-57.

McClean, S., & Crowe, W. (January 01, 2016). Making room for interactivity: using the cloud-based audience response system Nearpod to enhance engagement in lectures. Fems Microbiology Letters, 364, 6.)

Morling, B., McAuliffe, M., Cohen, L., DiLorenzo, T.M. (2008). Efficacy of personal response systems (“clickers”) in large, introductory psychology classes. Teaching of Psychology, 35 (1)(2008), pp.45-50.

Nearpod image, (April 8, 2018), retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nearpod_logo.png

Nearpod video, (August 31, 2016), video retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ThlqFu1qIlM&t=19s

Pascarella, E.T., & Terenzini, P.T. (2005). How college affects students. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA (2005).

Poirier, C.R. & Feldman, R. S. (2007), Promoting active learning using individual response technology in large introductory psychology classes. Teaching of Psychology, 34 (3)(2007), pp.194-196.

Poll Everywhere image, (April 8, 2018), retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6c/Poll_everywhere_logo.svg/2000px-Poll_everywhere_logo.svg.png

Prince, M. (2004). Does active learning work? A review of the research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93(4), 223-231.

Riggs, E. & Gholar, C. (2009). Strategies that promote student engagement: Unleashing the desire to learn. Corwin Press, Thousand Oaks, CA (2009).

(2010) Student Participation in the College Classroom: An Extended Multidisciplinary Literature Review, Communication Education, 59:2, 185-213.

Ryan, R.M., Deci, E.L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25 (2000), pp. 54-67.

Thomas, N. J., Brown, E. A., & Thomas, L. Y. (November 01, 2015). Use of student response and engagement systems in the collegiate classroom: An educational resources review. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 17, 59-61.

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.), University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1993).

Top Hat image, (April 8, 2018), retrieved from https://www.ohio.edu/instructional-innovation/images/TopHat_Wordmark_Purple_RGB.png

(Tornwall, J., e-mail, March 29, 2018).

Uhari, M., Renko, M., Soini, H. (2003). Experiences of using an interactive audience response system in lectures. BMC Medical (2003). retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/3/12

Zhu (2008). Teaching with clickers. Occasional Paper No. 22 Enter for research on Learning and Teaching, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. Retrieved from http://www.crit.umich.edu/publinks/occasional.php