Introduction

“Information is just bits of data. Knowledge is putting them together. Wisdom is transcending them.” —Ram Dass

“Most university students are intellectually timid … they are “good at absorbing information but slow to question the ideas they study.” — R.S. Hansen

A good place to begin to understand what is meant by critical thinking, reading, and writing is to consider how college work differs from other kinds of schoolwork you may have done.

First, think about the reading and writing you did in elementary and secondary school. Usually, elementary school children learn how to decode and write letters or characters; they might memorize grammar rules, learn basic history, and begin basic mathematics. In general, they develop a foundation for the higher order skills they will learn later. Does this sound familiar? You may have a non-traditional or different educational experience, but it is likely you went through similar stages.

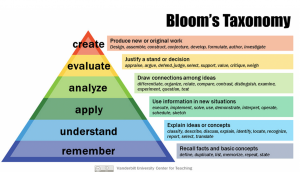

As children progress to middle school, high school, and college, their cognitive ability grows more complex, as you can see in the chart below:

(Source: Hansen, R.S. (n.d.). Ways in which college is different from high school. My CollegeSuccessStory.com.)

Elementary Education |

Secondary Education |

Higher Education |

|

|

|

|

||

Focus on Facts |

Simple Creativity & Originality |

Creation of New Knowledge |

|

Remember → Understand → Apply → Analyze → Evaluate → Create

|

||

These cognitive phases were mapped out by American educational psychologist, Benjamin Bloom, who created a system of verbs for classifying and measuring observable actions and help us understand cognitive activity in the brain at various stages of schooling. In other words, these are the verbs that a student must do to demonstrate learning. Below is one graphic representation of Bloom’s taxonomy: The most sophisticated of these skills are the top three. They involve more critical thinking and a more advanced stage of learning than those below. While the top three skills are most associated with college-work, you will likely use all of these skills in your university assignments.

“What we read, how we read, what we do with our readings, what we write, how we write, and what we do with our writing can be considered ‘critical’ if it involves analysis.”

(Hansen, n.d.)

Analysis

An analysis is not a summary. Summaries involve reporting concisely what an author has written. You do not include your own opinion or use judgmental vocabulary in a summary; you only include the opinions or judgments that come from the author or a source. When you analyze something, you do much more than summarize information or report an author’s opinions. Analysis means using your own views, perspectives, knowledge, or experiences.

Analysis can be a straightforward examination of each part, like an auto mechanic checking a car engine; however, in academic scholarship, it means bringing in your own perspective, opinions, observations, and evaluation.

We might analyze an author’s argument or data to see if it is strong; we might choose an element of a poem or literary work to study closely for significant elements like style, historical period, symbolism, rhyme and so forth. In the field of Engineering, one might analyze a design or code for ways to improve it.

Your purpose might be to make an argument, comparison, or connection, or offer an interpretation, reflection or evaluation. You might reach a different conclusion than the author of a study. You might report strengths or weaknesses, causes or effects, effectiveness, significance, or make an original connection. As you can see, analysis is a creative act.

Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing ultimately help to structure your thinking. This means, you know how to read for different purposes, and articulate and defend your views using support or evidence. These skills will enable you to join the wider academic community of knowledge-building, expansion, and credibility.

Asking Questions

Academic analysis begins with asking good questions about what you have seen or read. Learning to question respectfully everything you encounter. This practice can strengthen your critical thinking ability and skill at examining complex issues because it involves reflecting on what you’ve seen or read and evaluating its usefulness or significance. Furthermore, it helps you question the reliability of the flow of information to which you are exposed in media.

This practice will then lead to the ability to “read between the lines” when you hear, see, or read information. This enables you to make connections or find faults in logic. Reading between the lines means making inferences, catching symbolism, or seeing an indication.

Learn more about critical thinking, critical reading, and critical writing in the chapters to come.