6 – Information Literacy

Information and the technology that facilitates its dissemination are so common in our world today, we may not realize that we are functioning in a much larger world view of information.

Before you begin to study information literacy, take the survey below to see how much you already know or need to know.

SURVEY

1. Information literacy is synonymous with computer or technology literacy:

2. Information literacy consists primarily of search skills, such as the ability to use a database or search engine:

3. Information literacy consists of a combination of conceptual understandings, skills, and habits of mind:

4. Information literacy is closely related to critical thinking.

5. In my discipline (field of study) an understanding of research and scholarship is important.

6. Information literacy is needed only in courses which require research papers

7. Most students have received adequate information literacy instruction before they attend university.

8. Name one reason why scholars must be careful to acknowledge the sources they use in their own work:

9. Write a short (1-3 sentences) definition of information literacy. Please answer based on your current understanding — don’t look up the definition.

10. Write a short (1-3 sentences) definition of intellectual property. Please answer based on your current understanding — do not look up a definition.

Information Literacy in the Context of a Classroom

Let’s begin with a case from an actual classroom:

Casey’s Problem

Casey is completing an assignment for his environmental science course, in which he must develop an action plan for reducing the amount of plastic pollution in the ocean. His instructor, Dr. Singer, indicates all action plans must be supported with data from credible, scholarly sources. Casey’s initial Google search for sources brings millions of results. He spends a considerable amount of time reviewing multiple sources, and carefully selects sources that he thinks are scholarly, including a few that are on .edu websites. He then uses these to put together his plan. When he receives his grade, he is upset, because his professor tells him that most of the sources that he used were not appropriate for the assignment.

What did he do wrong?

Dr. Singer’s Problem

It is the same thing every semester. No matter how much Dr. Singer emphasizes that her students need to use scholarly sources, most students continue to use inappropriate sources. Usually, their reference pages contain a jumbled mess of websites and news articles. This semester, she even spent some class time with her students, specifically talking to them about how to identify scholarly sources, but they still seemed to struggle.

What more can she do?

Activity #1:

Write a short response describing your reaction to these situations. What do you think is causing Casey to struggle? What could Dr. Singer do to help Casey and other students overcome these challenges?

The Digital Information Environment

In the previous cases, Casey is a good student who worked hard on his project, and Dr. Singer is a dedicated instructor who wants her students to succeed. Yet, in this situation, both end up frustrated and confused. Casey’s story illustrates the complexity of the digital information environment and the challenges that students can face when trying to navigate this environment. Dr. Singer’s story raises the issue of how best instructors can help students develop the conceptual understandings and skills that they need to effectively engage with information. We live in a world in which we have access to vast amount of information, available in numerous formats, and accessible through multiple channels. To provide just a few examples, there are:

- 500 stories published each day by The Washington Post (Meyer 2016 (Links to an external site.))

- 28,000 active scholarly journals (Ware and Mabe 2015 (Links to an external site.))

- 1 million articles added to PubMed each year–about 2 per minute (Landhuis 2016 (Links to an external site.))

Although in some ways this makes research much easier, in other ways it can make research more challenging. In addition to the sheer volume of information, and the rapid pace that it comes at us, here are a few other reasons why navigating the information environment can be challenging:

Information Formats:

There are more information formats than ever before. But, nearly all of the information that we encounter now comes to us online. In print, it was easy to tell the difference between a newspaper, a magazine, and an academic journal, but online it is not as easy to distinguish between formats. For students, everything online may look like a website. This has sometimes been referred to as “container collapse (Links to an external site.).” (OCLC 2004 (Links to an external site.); Connaway 2018)

Decontextualized Information:

Much of the information that comes to us is also lacking context. Consider a traditional newspaper. The placement of a specific article would provide clues about the relative importance of the article–what page it was on, which section it was in, whether it was above or below the fold, the content of the articles that were next to it. Now, all we see is often disconnected stories (or just headlines) without the clues that would help us to determine accuracy and value. (Townsend, Lin Hanick, & Hofer, 2019

Misinformation or Disinformation:

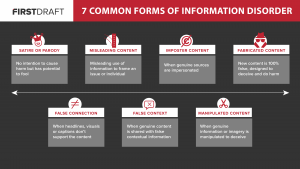

The speed at which information can be passed makes it very easy for inaccurate or misleading information to be spread. While this is sometimes done without the intent to cause harm, there are those who are deliberately creating and sharing false information. These information sources often take the form of real information sources and can be difficult to spot. The following provides a good overview of different types of misleading information that you may encounter: Forms of Information Disorder. (Wardle; Wardle & Derakshan, 2017

Audio for above Chart:

Audio for above Chart:

Source: Claire Wardle, 2017

Activity #2:

In addition to multiple information formats, lack of context, and misinformation, what other reasons do you think people have for sometimes struggling to navigate the information environment? What roles do they play within this environment? Write a brief response to these questions.

You play dual roles within this information environment, as both an information consumer and an information creator, and you have different rights and responsibilities related to each role.

Students in the Digital Information Environment

Below are some roles that you play within an information environment. Read about your rights and responsibilities related to each role.

Students as Information Consumers

In their academic, professional, and personal lives, students all have to find and use information. They have to find the information needed to complete their academic assignments, but they also must find the information needed to navigate daily life and make numerous decisions, from the significant to the mundane. Wherever and however they search for information, they are likely to receive a significant number of results. They will then need to make choices about which information sources to use and trust.

Students as Information Creators

Students also create information. They write research papers, stories, and poems and create research posters, artwork and music. In many cases, their creations are shared only with their instructors and perhaps a few classmates. Increasingly, however, they are being expected to share with a wider audience, as part of the growing emphasis on undergraduate student research. Students also create and share information in their personal and professional lives, including

posting their thoughts and opinions on various social media platforms.

How well do you think students navigate this environment? The videos below highlight major findings from reports on how well students do.

“For over three-fourths (84%) of the students surveyed, the most difficult step of the course-related research process was getting started. Defining a topic (66%), narrowing it down (62%), and filtering through irrelevant results (61%) frequently hampered students in the sample, too.”

(Head & Eisenberg, 2010, p.3

The News Study presents findings about how a sample of U.S. college students gather information and engage with news in the digital age. The following video summarizes the major findings from an online survey of 5,844 respondents and telephone interviews with 37 participants from 11 U.S. colleges and universities selected for their regional, demographic, and red/blue state diversity.

“Our study’s findings suggest that most young news consumers feel overwhelmed by the volume of news and many feel they are unable to discern true from false news.”

(Head et al, 2018, p. 37)

How Do College Graduates Solve Information Problems in the Workplace?

What happens to college students once they graduate and make the critical transition from campus to the workplace?

Watch this video to learn about the study and its findings:

“…when we specifically asked employers to assess how adept these new graduates are at finding and using information, many noted that the online proficiency they had prized at the recruiting stage turned out, in many cases, to be dismayingly limited. Most employers needed and expected more from their new hires, including research done more rigorously and more flexibly.” (Head, 2012, p. 11)

A recent report published by the Stanford History Education Group focused on students’ ability to evaluate information found online. The major conclusion from this study is indicated below:

Information Literacy

The term “information literacy” has been in use for more than 40 years, and the definition has evolved over this time period. In 2015, the Association of College and Research Libraries published the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education, which provides an updated conception of information literacy. Rather than a list of skills, the Framework outlines six broad concepts that are central to information literacy:

Watch this video to learn about the definition of information literacy:

Below are the Six Core Concepts of the Information Literacy for Higher Education Framework:

Authority is Constructed and Contextual: Information sources have different levels of authority. Context may determine the level of authority needed.

Information Creation as a Process: Information sources are created through differing processes. The creation process and format may impact the actual or perceived value.

Information Has Value: Information has financial, social, and personal value, and there are legal and ethical guidelines regarding its creation, access, and use.

Research as Inquiry: Research is an iterative process focusing on answering questions. These answers often create new questions.

Scholarship as Conversation: Scholars engage in ongoing debates in which ideas are revised, accepted, or rejected. Each information source may represent a single “voice” in the conversation.

Searching as Strategic Exploration: There are multiple search tools and strategies. The search process should vary based on information need.

Information Literacy and Critical Thinking

There has long been recognition of the close connection between information literacy and critical thinking. Like information literacy, critical thinking is one of those terms for which there have been multiple definitions. However, a look at just a couple of these definitions can help to make apparent how closely related the two concepts are:

“Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. “

Information literacy is also closely connected to other concepts such as media literacy, digital literacy, and visual literacy.

“Information literacy” is the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.

“Media Literacy is a 21st century approach to education. It provides a framework to access, analyze, evaluate, create and participate with messages in a variety of forms — from print to video to the Internet. Media literacy builds an understanding of the role of media in society as well as essential skills of inquiry and self-expression necessary for citizens of a democracy.” (Center for Media Literacy

“Digital literacy is the ability to use information and communication technologies to find, evaluate, create, and communicate in- formation, requiring both cognitive and technical skills.” (American Library Association

“Visual literacy is defined as the ability to read, write and create visual images. It is a concept that relates to art and design but it also has much wider appli-cations. Visual literacy is about language, communication and interaction. Visual media is a linguistic tool with which we communicate, exchange ideas and navigate our highly visual digital world.” (Visual Literacy Today

Understanding the Research Process

Let’s look at another case:

Mia’s Problem

Mia is writing a paper for her psychology course. She is interested in determining the most effective way to treat depression in college students. She uses the advanced search in PsycInfo, limiting her results to peer reviewed sources published within the last 5 years. Although she finds multiple scholarly articles, she struggles to make sense of the results. One source recommends one treatment, another recommends something completely different. Some of the recommendations even seem to directly contradict each other. She is so frustrated–why can’t she find one clear answer to her research question?

In this situation, Mia clearly has some knowledge about how to research in psychology. She selects an appropriate database, uses advanced search techniques, and can identify peer reviewed sources. However, there is something that is still causing her to struggle, something that she is missing about the research process.

ACTIVITY #3: Write a short reaction to Mia’s situation. She clearly understands how to find information but doesn’t seem to really grasp the purpose of research. What would she need to understand about research and scholarship in order to make sense of her results?

Conversation, Inquiry, and Value

Mia’s story illustrates the difference between a skills-based understanding of information literacy and a conceptual understanding. She has research skills, but she lacks understanding of certain concepts that would help her to make sense of her results.

In this case, Mia seems to be struggling to understand the concepts of Scholarship as Conversation and Research as Inquiry. If she recognized that scholars are always debating each other through their research, she would be less frustrated by the ambiguous nature of her results. And, if she recognized research as a process in which answers often lead to new questions, she would be less inclined to seek a single “right” answer to her question.

The Association of College & Research Libraries (2015) proposes the following definition of Information Literacy:

“Information literacy is the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning “ (ACRL, 2015)

Let’s look at these concepts in more detail:

Information Has Value

- Information has many types of value, both for the consumer and the creator

- There are legal and ethical guidelines for how information can be created, accessed, and shared

For a brief introduction to the concept, and the challenges that students might face related to it, watch the short (1:24) video below:

Information has value in many different contexts – personal, educational, social, political, financial, etc. There are a number of factors (political, economic, legal) that influence the creation, access, and distribution of information. Novice learners may struggle to understand the value of information, especially in an environment where nearly all information appears to be available for free online. Experts, however, understand their responsibilities as consumers and creators of information, which involves making deliberate choices about how they access and share information. In addition, experts recognize that not everyone has equal access to information or the equal ability to make their voice heard.

Below are some examples of the knowledge practices and dispositions for Information Has Value.

| Knowledge Practices: Demonstrations of ways in which learners can increase their understanding of these information literacy concepts | Dispositions: Address the affective, attitudinal, or valuing dimension of learning |

| Give credit to the original ideas of others through proper attribution and citation | Respect the original ideas of others |

| Articulate the purpose and distinguishing characteristics of copyright, fair use, open access, and the public domain | Value the skills, time, and effort needed to produce knowledge |

| Make informed choices regarding their online actions in full awareness of issues related to privacy and the commodification of personal information | See themselves as contributors to the information marketplace rather than only consumers of it |

| Recognize issues of access or lack of access to information sources | Are inclined to examine their own information privilege |

While information may often seem to be free, it actually has significant value, both for the information consumer and creator. Because information is valuable, there are multiple legal and ethical guidelines relating to information. An understanding of this concept will help you make informed and ethical decisions in regards to the creation, access, use, and sharing of information.

Research as Inquiry

- Research is an iterative process focused on answering questions, solving problems, or creating new knowledge

- Finding an answer often leads to new questions

Research is focused on answering questions (which can be personal, academic, or social). Experts usually see research as a process focused on problems or questions within a discipline, or between disciplines, that are unanswered or unresolved. They recognize that research is rarely a simple, straightforward search for one “perfect” answer or source; instead, it is an iterative, open-ended, and messy process in which finding answers often leads to new questions. Expert researchers are able to accept ambiguity and recognize the need for adaptability and flexibility when they search. As students progress, they are able to ask increasingly sophisticated research questions and used more advanced research methods.

Watch the following video to explain how students struggle and how these are resolved through a better understanding of information literacy.

Below are some examples of the knowledge practices and dispositions for Research as Inquiry.

| Formulate questions for research based on information gaps or on reexamination of existing, possibly conflicting, information | Consider research as open-ended exploration and engagement with information |

| Synthesize ideas gathered from multiple sources | Value intellectual curiosity in developing questions and learning new investigative methods |

| Draw reasonable conclusions based on the analysis and interpretation of information | Value persistence, adaptability, and flexibility and recognize that ambiguity can benefit the research process |

| Use various research methods, based on need, circumstance, and type of inquiry

|

Seek multiple perspectives during information gathering and assessment |

Research is an iterative process in which finding answers usually creates new questions. An understanding of this concept will help students to recognize that research requires patience, persistence, and flexibility, and will prepare them to make sense of the often ambiguous nature of their search results, rather than always seeking a single “right” answer.

Scholarship as Conversation

- Scholars participate, through their work, in ongoing discussions or debates in which ideas or findings are reviewed, evaluated, accepted, or sometimes, rejected

- There are often specific methods or modes of conversation that must be learned before one can enter the discussion

Scholars, researchers, and professionals within a field engage in ongoing discussions in which ideas are continually being developed, debated, challenged, and, in some cases, rejected. While there are some topics for which accepted answers have been established through this process, in most cases there are often multiple competing perspectives on a topic or question. Experts are able to locate, navigate, comprehend, and contribute to the conversations within their discipline or field. They also recognize that providing appropriate attribution to relevant previous research is an obligation of participating in this conversation.

As you are developing your information literacy, you should be learning to see yourself as a possible contributor to these conversations, although you may first need to learn the “language” of the discipline (accepted research methods, standards for evidence, forms of attribution) before you can fully participate. An understanding of this concept will help you to better evaluate the relevance of specific information sources, as well as start to recognize your own role within the conversation.

Below are some examples of the knowledge practices and dispositions for Scholarship as Conversation.

| Cite the contributing work of others in your own information production | Seek out conversations taking place in your research area |

| Identify the contributors that particular sources make to your discipline’s knowledge | Recognize that you are often entering into an ongoing scholarly conversation when you join a discipline or major field of study. The conversation likely began long ago. |

| Summarize the changes in scholarly perspectives and theories that have taken place in your field of study over time | Suspend judgment on a particular piece of scholarship until you understand the context . |

| Contribute to scholarly conversations at an appropriate level. | See yourself as an information creator as well as consumer. |

Let’s look at another case:

Luke’s Problem

![]()

After graduating from Ohio State last spring, Luke took a job with new corporation nearby. He has just been assigned his first solo task. He needs to track the public reaction to a product that his company recently released and give a presentation to the design team in which he analyzes the reaction and makes recommendations for potential revisions. Luke is excited to get started, since he always did very well on all of his research assignments. But when he tries to use the research process he learned when he was a student–using an academic database and searching for peer reviewed articles, he quickly runs into problems. Although this process has always worked for him in the past, in this case, he is not able to find any useful information for his presentation. He is starting to panic. How can he find the information that he needs?

In this situation, the research process that served Luke well as a student is not working for him when faced with a real information need. He learned how to search for information as a student, but there is something that is preventing him from having the same success in the workplace.

ACTIVITY #4:

Take a few minutes to write a reaction to Luke’s situation. Why is his normal research process, developed over years as a student, no longer working for him? What would he need to understand about research and information to use to enable him to succeed at his project?

Information Creation and Exploration

During his time at Ohio State, Luke clearly learned how to complete research assignments in an academic context. But he is missing underlying conceptual knowledge about research and information that would allow him to have the same level of success in his workplace. In this case, Luke is having trouble recognizing that Authority is Constructed and Contextual and Searching is Strategic Exploration. He knows that scholarly journal articles are authoritative sources for college research papers, but is not able to identify what an authoritative source would be when in a different context. And, he doesn’t seem to understand that he may need to vary his search process based on his specific information need, rather than relying on the familiar process that has always worked for him in the past.

Let’s look at the three remaining core concepts:

Authority is Constructed and Contextual

- Information sources have different levels of authority

- Authority can be based on multiple factors, including education, experience, or social position

- Context can determine the level of authority needed

Information sources have different levels of authority. The authority of an information source is due, at least in part, to the credibility and expertise of the information creator. There are different types of authority or expertise, but having expertise in one area does not imply expertise in others. Experts recognize that the context in which information is needed and will be used can impact the level of authority that is needed, or what would be considered authoritative. Students who grasp this concept are able to examine information sources and to ask relevant questions about origins, context, and suitability for the current information need.

Watch this video to get a better understanding of this concept: https://youtu.be/YaNpB1WF-EI

Below are some examples of the knowledge practices and dispositions for Authority is Constructed and Contextual.

| Are able to define different types of authority, such as subject expertise (e.g., scholarship), societal position (e.g., public office or title), or special experience (e.g., participating in a historic event) | Motivate themselves to find authoritative sources, recognizing that authority may be conferred or manifested in unexpected ways |

| Use research tools and indicators of authority to determine the credibility of sources, understanding the elements that might temper this credibility | Develop awareness of the importance of assessing content with a skeptical stance and with a self-awareness of their own biases and worldview |

| Understand that many disciplines have acknowledged authorities in the sense of well-known scholars and publications that are widely considered “standard,” and yet, even in those situations, some scholars would challenge the authority of those sources | Question traditional notions of granting authority and recognize the value of diverse ideas and worldviews |

| Acknowledge they are developing their own authoritative voices in a particular area and recognize the responsibilities this entails, including seeking accuracy and reliability, respecting intellectual property, and participating in communities of practice | Develop and maintain an open mind when encountering varied and sometimes conflicting perspectives |

Information sources can have different levels of authority. Determining the authority of a source involves a consideration of the expertise and position of the information creator. A source that is considered authoritative in one context may not be considered authoritative in another context. An understanding of this concept will help you make good choices when determining which sources are relevant and appropriate for your specific information need.

Information Creation as a Process

- Information is created in differing formats for differing purposes

- The creation process and format can impact the actual or perceived value of an information source

Information products are created by different processes and come in many formats, which reflect the differences in the creation process. Some information formats may be better suited for conveying certain types of information or meeting specific information needs. Understanding how and why an information product was created can help to determine how that information can be used. Experts recognize that information products are valued differently depending on the context, and the creation process for an information source, as well of the format a source, can influence the actual or perceived value of an information source.

Watch this video for better understanding of Information Creation: https://youtu.be/zKxgF7xqAFs

Below are some examples of the knowledge practices and dispositions for Information Creation as a Process.

| Articulate the capabilities and constraints of information developed through various creation processes | Are inclined to seek out characteristics of information products that indicate the underlying creation process |

| Assess the fit between an information product’s creation process and a particular information need | Value the process of matching an information need with an appropriate product |

| Recognize that information may be perceived differently based on the format in which it is packaged | Understand that different methods of information dissemination with different purposes are available for their use |

| Articulate the traditional and emerging processes of information creation and dissemination in a particular discipline | Accept the ambiguity surrounding the potential value of information creation expressed in emerging formats or modes |

Information sources come in a variety of different formats. The format of the source may impact the actual or perceived value of that source, and certain formats may be considered more or less acceptable to use, depending on the context. An understanding of different formats of information, as well as the related creation processes, can help you in determining when and how to use a specific information source, as well as help you make informed decisions regarding the appropriate format(s) for your own information creations.

Source Comparison

WORKSHEET

COMPARISON OF POPULAR AND SCHOLARLY SOURCES |

|

| My Name: | |

| My Field: | |

Popular Source |

|

| Name of article: | |

| Date of article: | |

| Length (number of pages) of the article: | |

| Author(s): | |

| Information about author(s) and where the information came from: | |

| Name of publication; information about publisher: | |

| Type of source: | |

| Source audience and purpose: | |

| Article characteristics: | |

| Evaluation of article’s perspective: | |

| PROs | |

| CONS | |

| How/where I found the article: | |

| Link: | |

| Date I accessed the article: | |

| Citation |

|

Scholarly Source |

|

| Name of article: | |

| Date of article: | |

| Length (number of pages) of the article: | |

| Author(s): | |

| Information about author(s) and where the information came from: | |

| Name of publication; information about publisher: | |

| Type of source: | |

| Source’s audience and purpose: | |

| Article characteristics: | |

| Evaluation of article’s perspective: | |

| Purpose of article: | |

| PROS | |

| CONS | |

| How/where I found the article: | |

| Link: | |

| Date I accessed the article: | |

| Citation: |

Activity #6:

Searching as Strategic Exploration

- Expert searchers can use multiple search tools and search strategies, and change their search based on information need

- Experts demonstrate persistence when searching but are open to new directions based on initial findings

Searching for information is often nonlinear and iterative, requiring the evaluation of a range of information sources and the mental flexibility to pursue alternate avenues as new understanding develops. The information searching process is a complex process that is influenced by cognitive, affective, and social factors. While novice learners may only use a limited number of search tools and strategies, experts understand the properties of various information search systems and make informed choices when determining search strategy and search language. Expert searchers shape their search to fit the information need, rather than relying on the same strategies, search systems, and search language without regard for the context of the search.

Watch the video for better understanding: https://youtu.be/DxInwu454Dc

Below are some examples of the knowledge practices and dispositions for Searching as Strategic Exploration.

| Match information needs and search strategies to appropriate search tools | Understand that first attempts at searching do not always produce adequate results |

| Design and refine needs and search strategies as necessary, based on search results | Recognize the value of browsing and other serendipitous methods of information gathering |

| Understand how information systems (i.e., collections of recorded information) are organized in order to access relevant information | Persist in the face of search challenges, and know when they have enough information to complete the information task |

| Use different types of searching language (e.g., controlled vocabulary, keywords, natural language) appropriately |

Seek guidance from experts, such as librarians, researchers, and professionals |

Searching is an iterative* process that requires an awareness of a broad range of search tools and the ability to use these tools effectively, as well as an understanding of how to refine or revise a search based on initial results. It is important to change a search based on the information need, rather than using the same search tools and strategies in each situation. If you understand this concept, you will be able to make appropriate decisions about where and how to search for information in different contexts.

*involving repetition of steps; utilizing the repetition of a sequence of operations or procedures multiple times.

Activity #7:

In this assignment, you will learn a little about American politics. First, you will take a “political party quiz” to see where your beliefs and values fit in the American political scene. The purpose of this exercise is to help you understand different positions on issues, not to recruit you to any political affiliation. You do not need to share your results with anyone.

Look at each of the following links:

- Political Party Quiz: https://www.people-press.org/quiz/political-party-quiz/

- Overview of political party beliefs: https://www.diffen.com/difference/Democrat_vs_Republican

- Allsides.com: https://www.allsides.com/unbiased-balanced-news

Choose any article from allsides.com within the past 2 years, and look at the headlines across at least 3 news sources — choose 1 from the left (liberal), 1 from the center, and 1 from the right (conservative). Take a Screenshot of your 3 headlines. Then:

1) read all 3 versions of the article.

2) Respond to the following:

-

Comment on what you notice about the word choice itself within the 3 headlines (similarities and differences, role of bias, etc.)

-

Discuss your position on the topic. (How does your environment, upbringing, culture, religion, socioeconomic status, etc. affect your point of view of the topic?)

-

Discuss source credibility, purpose, context, bias, and validity across the three articles in relation to the topic.

Try NOT to criticize each article individually, but instead look across articles for instances of similarities/differences/evaluation measures.

SAMPLE

On June 25, 2020, the top headlines on allsides.com address the public’s perception on reparations for slavery. Headlines from The Daily Caller (right), Reuters (Center) and the New York Times (Left) can be seen pictured above. The headlines themselves differ in word choice, tone, and presentation, with the conservative Right highlighting results of a recent poll, the Center acknowledging growth of more public awareness despite poll results, and the Left choosing a key quotation as the headline.

In the headline from the Daily Caller, the wording of “large majority” sends a strong message to its readers that public opinion was not even close, confirming the conservative point of view. Additionally, the inclusion of “using taxpayer money” also highlights to the Right-leaning readers that many of them will most likely be “paying” for these reparations with their own taxes, thus projecting the view that reparations are negative. The headline from Reuters is more upfront, actually citing the poll referenced in both headlines from the Right and Center articles. It additionally confirms the results of the poll, while still being upfront about the change in the U.S.’s public perception longitudinally (more aware of racial inequality). The headline from The New York Times chooses a quotation, simple but containing a strong message, to emphasize the importance of a united front to fight for their cause. They clearly choose to address the topic without a reference to the poll in their headline, which makes sense considering the results were not compatible with their target audience’s point of view.

Though I am still trying to understand my exact position on this topic, I am sure that many environmental factors influence me. I was raised in a white, Christian family with conservative values in a rural area. Growing up, there was one African American student in my school (K-12) of over 1,000 students, and the history lessons I received were from white, conservative teachers. After attending and graduating from a predominantly white, Christian University, I spent several years teaching in Asia . My worldview completely expanded and changed through exposure to new people and cultures and experiencing both love and hate as a resident alien in a foreign country. Right now I am still learning and growing in my understanding of reparations.

Looking into the 3 news sources themselves, The Daily Caller is a right-winged news website founded in 2010 by Fox news host Tucker Carlson and Neil Patel. It is a member of the White House press pool, and is noted to have published false stories (i.e. climate change) and stories from White Supremacists ( Jason Kessler and Peter Brimelow ). By 2013, the site was receiving over 35 million views a month, surpassing sites such as The Washington Times , Politico , and Forbes . Founded in 1851, Reuters is the world’s leading international multimedia news agency. It is headquartered in London, United Kingdom. In 2018, Reuters was named the winner of two Pulitzer Prizes on international reporting, and multiple sources have praised Reuters for being the least or minimally biased due to proper citing of information with an attempt to cover both sides of an issue. The New York Times is an American daily newspaper, founded and continuously published in New York City since September 18, 1851 by The New York Times Company. The New York Times is funded through advertising and subscription fees. It utilizes emotionally loaded language in their headlines, and while story selection is typically balanced, wording tends to lean left in most cases. A factual search shows The New York Times has made false claims in reporting but always makes corrections to those stories as soon as new information is available.

After reading each article, a biased perspective is evident throughout all three. It is obvious to me that the articles try their best to reach and make their target audience happy, choosing to include or exclude key anecdotes or facts based on what their readers will want to see. In the New York Times article, the recent poll results confirming Americans’ anti-reparations point of view were not mentioned. Instead, the article spent pages highlighting past racial injustices, interwoven with descriptive and powerful photographic images. In the Reuters article, it was interesting that when reporting on the results of the poll, Reuters chose to first mention “ only one in five respondents agreed the United States should use “taxpayer money to pay damages to descendants of enslaved people in the United States,” before later pointing out that only one in ten white respondents and about half of Black respondents endorse it. Additionally, perspectives from both conservative and liberal politicians were provided, which tried to create a minimally-biased piece. From the headline to the conclusion, The Daily Caller article tried its best to validate the survey results, citing sample sizes, dates surveyed, and expert opinions.

Activity #8:

In this assignment, you will use a scholarly database (OSU library, google scholar, etc.), to complete and submit the attached worksheet. (Parts 1 and 2)

In part 1, starting with a general idea for a topic, you will use a database to search and narrow your topic enough to find one peer-reviewed, scholarly source. This source MUST have a publication date from 2010-2018, as it will be used as a resource for several future assignments.

In part 2, you will write a short (1 page) reflection on your ‘choosing and narrowing a research topic’ process. This reflection can include but is not limited to addressing 1. How you chose and narrowed to your subtopic/research questions, 2. Your understanding of databases and search engines specific to your field and subtopics, 3. The practical strategies/adjustments used to narrow your topic and find relevant sources, 4. Explaining your choice is exploring and choosing your specific source for inclusion in this assignment, and 5. Outlining any challenges/your reactions to the challenges as they arose throughout the search process.

Please answer all questions, and attach the worksheet when finished! See the attached sample as a guide.

———————————————–

References

American Library Association. (n.d.) Digital literacy. Retrieved from https://literacy.ala.org/digital-literacy/

American Library Association. (1989). Presidential committee on information literacy: Final report. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/whitepapers/presidential

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2015). Framework for information literacy for higher education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Branstiter, C.W. & Halpern, R. (2017). “But how do I know it’s a good source?” Authority is constructed in social work practice (Links to an external site.).” In Godbey, S., Wainscott, S.B., & Goodman, X. (Eds.), Disciplinary applications of information literacy threshold concepts, (pp. 25-36). Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Center for Media Literacy. (n.d.). Media literacy: A definition and more. Retrieved from https://www.medialit.org/media-literacy-definition-and-more

Connaway, L.S. (2018, Jun 20). What is “container collapse” and why should librarians and teachers care? OCLC. Retrieved from http://www.oclc.org/blog/main/what-is-container-collapse-and-why-should-librarians-and-teachers-care/

Couture, J. & Ladenson, S. (2017). “Empowering, enlightening, and energizing: Research as inquiry in women’s and gender Studies (Links to an external site.),” University Libraries Faculty & Staff Contributions, 98. In Godbey, S., Wainscott, S.B., & Goodman, X. (Eds.), Disciplinary applications of information literacy threshold concepts, (pp. 177-189). Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Foasberg, N. M. (2015). From standards to frameworks for IL: How the ACRL framework addresses critiques of the standards. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 15(4), 699-717.

Grafstein, A. (2002). A discipline-based approach to information literacy. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 28(4), 197-204. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0099133302002835

Grafstein, A. (2017). Information literacy and critical thinking: context and practice. In Pathways Into Information Literacy and Communities of Practice (pp. 3-28). Chandos Publishing.

Haigh, J. (2017). Teaching the teachers: The value of information for educators (Links to an external site.). In Godbey, S., Wainscott, S.B., & Goodman, X. (Eds.), Disciplinary applications of information literacy threshold concepts, (pp. 163-173). Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Hassel, H., Reddinger, A., & Van Slooten, J. (2011). Surfacing the structures of patriarchy: teaching and learning threshold concepts in women’s studies (Links to an external site.). International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 5(2), Article 18.

Head, A. J. (2012). Learning curve: How college graduates solve information problems once they join the workforce. Project Information Literacy. Retrieved from https://www.projectinfolit.org/uploads/2/7/5/4/27541717/pil_fall2012_workplacestudy_fullreport_revised.pdf

Head, A. J. & Eisenberg, M. B. (2009). Lessons learned: How college students seek information in the digital age. Project Information Literacy. Retrieved from https://www.projectinfolit.org/uploads/2/7/5/4/27541717/pil_fall2009_finalv_yr1_12_2009v2.pdf

Head, A. J., Wihbey, J., Metaxas, P. T., MacMillen, M. & Cohen, D. (2018). How students engage with news: Five takeways for educators, journalists, and librarians. Project Information Literacy. Retrieved from https://www.projectinfolit.org/uploads/2/7/5/4/27541717/newsreport.pdf

Heuer, M. B. (2017). Using the frame information creation as a process to teach career competencies to advertising students (Links to an external site.). In Godbey, S., Wainscott, S.B., & Goodman, X. (Eds.), Disciplinary applications of information literacy threshold concepts, (pp. 79-91). Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Hofer, A. R., Townsend, L., & Brunetti, K. (2012). Troublesome Concepts and Information Literacy: Investigating Threshold Concepts for IL Instruction (Links to an external site.). Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 12(4), 387–405.

Hofer, A. R., Lin Hanick, S., & Townsend, L. (2019). Transforming Information Literacy Instruction: Threshold Concepts in Theory and Practice. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

Kinchin, I.M. (2010). “Solving Cordelia’s Dilemma: Threshold Concepts within a Punctuated Model of Learning. (Links to an external site.)” Journal of Biological Education (Society of Biology) 44 (2): 53–57. doi:10.1080/00219266.2010.9656194.

Kuglitsch, R. (2017). Widening the threshold: Using scholarship as conversation to welcome students to science (Links to an external site.). University Libraries Faculty & Staff Contributions. In Godbey, S., Wainscott, S.B., & Goodman, X. (Eds.), Disciplinary applications of information literacy threshold concepts, (pp. 263-274). Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Landhuis, E. (2016, Jul 21). Scientific literature: Information overload. Nature. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v535/n7612/full/nj7612-457a.html

Meyer, R. (2016, May 26). How many stories do newspapers publish per day? The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/05/how-many-stories-do-newspapers-publish-per-day/483845/

Meyer, J.H.F. and Land, R. (2003) Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge: linkages to ways of thinking and practicing. In: Rust, C. (ed.), Improving Student Learning – Theory and Practice Ten Years On (Links to an external site.). Oxford: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development (OCSLD), pp 412-424.

Meyer, J.H.F., Land, R. and Baillie, C. (Eds.) (2010). Threshold Concepts and Transformational Learning (Links to an external site.). Sense Publishers.

Moreton, E. and Conklin, J. (2018). From Novice to nurse: Searching for patient care information as strategic exploration (Links to an external site.). In Godbey, S., Wainscott, S.B., & Goodman, X. (Eds.), Disciplinary applications of information literacy threshold concepts, (pp. 289-301). Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries.

OCLC (2004). 2004 information format trends: Content, not containers. Retrieved from https://www.oclc.org/content/dam/oclc/reports/2004infotrends_content.pdf

Saunders, L. (2012). Faculty perspectives on information literacy as a student learning outcome. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 38(4), 226-236.

Scriven, M., & Paul, R. W. (1987). Defining Critical Thinking, Draft statement written for the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking Instruction. Retrieved from https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766

Shanahan, M. (2016). Threshold concepts in economics (Links to an external site.). Education+ Training, 58(5), 510-520.

Smith, C. (2012). Ethical behaviour in the e-classroom: What the online student needs to know. Chandos Publishing.

Smith, R. (1997). Philosophical shift: Teach the faculty to teach information literacy. ACRL 8th National Conference Papers. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/whitepapers/nashville/smith

Stanford History Education Group. (2016). Evaluating information: The cornerstone of civic online reasoning. Retrieved from https://stacks.stanford.edu/file/druid:fv751yt5934/SHEG%20Evaluating%20Information%20Online.pdf

Townsend, L., Brunetti, K., & Hofer, A. R. (2011). Threshold concepts and information literacy (Links to an external site.). portal: Libraries and the Academy, 11(3), 853-869

Trend, R. (2009). The power of deep time in geoscience education: Linking ’interest’, “threshold concepts” and “self-determination theory (Links to an external site.).” Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai, Geologia, 54(1), 7–12.

Truscott, J. B., Boyle, A., Burkill, S., Libarkin, J., & Lonsdale, J. (2006). The concept of time: Can it be fully realised and taught? (Links to an external site.). Planet, 17(1), 21-23. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.11120/plan.2006.00170021 (Links to an external site.)

Visual Literacy Today. (n.d.) What is visual literacy? Retrieved from https://visualliteracytoday.org/what-is-visual-literacy/

Wardel, C. (2017). 7 common forms of information disorder. First Draft. Retrieved from https://firstdraftnews.org/en/education/curriculum-resource/information-disorder-useful-graphics/. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/)

Wardel, C. & Derakshan, H. (2017). Types of information disorder. First Draft. Retrieved from https://firstdraftnews.org/en/education/curriculum-resource/information-disorder-useful-graphics/. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/)

Ware, M. & Mabe, M. (2015). The STM Report: An overview of scientific and scholarly journal publishing. Retrieved from https://www.stm-assoc.org/2015_02_20_STM_Report_2015.pdf

Witek, D. (2016). The past, present, and promise of information literacy. (cover story). Phi Kappa Phi Forum, 96(3), 22-25.

All images, except otherwise noted, are from Ohio State’s Signature Photo Gallery, and are available for use by Ohio State users. All images are the property of The Ohio State University and are copyright protected.

Video Citations

The videos used in this module were originally created by Jane Hammons for Steely Library (Northern Kentucky University), and were published under a Creative Commons License allowing for reuse and modification. Videos may have been slightly modified for the purposes of this course. In addition, copies of the videos were uploaded to the YouTube channel for the Teaching and Learning Department within the Ohio State University Libraries. Links to original and revised versions are available below:

- Steely Library. (2018). Information Has Value (Links to an external site.). (Original)

- Steely Library. (2018). Scholarship as Conversation (Links to an external site.). (Original)

- Steely Library (2018). Research as Inquiry (Links to an external site.). (Original)

- Ohio State University Libraries. Information Has Value (Links to an external site.).

- Ohio State University Libraries. Scholarship as Conversation (Links to an external site.)

- Ohio State University Libraries. Research as Inquiry (Links to an external site.).

- Steely Library. (2018). Authority is Constructed and Contextual (Links to an external site.)(Original)

- Steely Library. (2018). Information Creation as a Process (Links to an external site.)(Original)

- Steely Library (2018). Searching as Strategic Exploration (Links to an external site.) (Original)

- Ohio State University Libraries. Authority is Constructed and Contextual (Links to an external site.)

- Ohio State University Libraries. Information Creation as a Process (Links to an external site.)

- Ohio State University Libraries. Searching as Strategic Exploration (Links to an external site.)

Videos were created using PowToon.

All photographic images in the module, except otherwise noted, are from Ohio State’s Signature Photo Gallery (Links to an external site.), and are available for use by Ohio State users. All images are the property of The Ohio State University and are copyright protected.