Chapter 14 – Columbus, Malaria and America

Every so often a book comes along that is so rich and compelling that an account of it cries out for inclusion in another book. We speak here of a book entitled 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created by Charles Mann, which is an account of the impact of Columbus’ arrival in America. One chapter, in particular, is relevant to us because it details how the advent of malaria, an unintended gift of Columbus to the Americas, impacted not only the natives whose naïve immune systems were not able to prevent the disease or fight it off when acquired, but the European colonists who lived a little further to the north. This, of course, is one of the major impacts of insect-borne disease everywhere as human invaders spread not only their cultural influence but the diseases they harbor into new lands. What makes this story so compelling is that malaria became disconnected from Columbus in North America and continued to have an impact not only on the health of indigenous people but also on the economies and societal structure in North America in locations quite distant from the places Columbus actually visited. It is a story worth retelling as a result, particularly when, as it is here, it can be augmented by updates from modern biology.

Columbus Introduces Malaria

As many of us know from our elementary school education, Columbus, an Italian explorer, set forth from Spain on a quest to find India and set up commerce in spices. Despite his own Italian nationality, he persuaded Queen Isabella I of Castile (Spain) to fund the trip, and in 1492 he set off for the East Indies—the first of four trips. The plan was to sail west and end up in what is now Japan. But, instead of achieving that goal, Columbus landed on the Bahamian archipelago and ultimately set up shop on the island of Hispaniola, which today is comprised of the nations of Haiti on the west and the Dominican Republic on the eastern end of the island. At the time of Columbus, the island was populated by indigenous people called the Tiano Ameridians.

Columbus returned to Hispaniola in 1493 and proceeded to establish the town of La Isabela, named in honor of Queen Isabela. It was the first step in the colonization of the American continent. A cache of letters written by Columbus during this period was discovered in 1989 and provides intriguing details about the conditions on the island. One notation was that “it rained a lot.” The second point of interest is that Columbus noted that many of his people were stricken by a condition known as “tertian fever,” which derives from the Latin for three and describes waves of sickness that recurred every third day. From the modern perspective, it is likely that Columbus was describing malaria.

According to David Cook, author of “Sickness, Starvation and Death in Early Hispaniola,” malaria did not exist in humans prior to Columbus’ arrival. The simian version of malaria (a different strain than what affects humans) may have been present among monkeys on Hispaniola, but there is no evidence to suggest that the malarial scourge had visited the natives on the island prior to the time that Columbus landed. This meant that the Tiano Amerindians would be considered by epidemiologists to be a naïve population whose immune systems had never encountered the disease. As a result, the natives were highly susceptible to malaria when it arrived. The Europeans, in contrast, probably enjoyed some level of immunity from prior exposure. It is highly likely that Columbus brought malaria to America since the disease was common in Europe. Columbus, of course, blamed the natives for making his men sick and singled out the Tiano women, in particular, because they were “disheveled and immodest” in appearance. This is a common approach to understanding disease transmission in the days before the germ theory of disease took route in biology (see Chapter 24 for more detail on this topic).

As previously noted by Columbus himself, it rained a lot on Hispaniola. It was also (and still is) warm for most of the year—two ideal conditions for producing a bumper crop of mosquitoes. Columbus and his men appear to have provided the inoculum, that is to say the malaria Plasmodium, thus assuring that the pathogen, the primary host, and the vector were present in abundance. As a result, a disease that did not appear to exist on Hispaniola prior to Columbus’ arrival became endemic thereafter. Sadly, the Caribbean has been suffering from malaria and its effects ever since.

Malaria Spreads North

The second chapter of this story takes place farther north on the North American continent. It is not known precisely how much of the malaria that originated in the Caribbean after Columbus, moved north to the American mainland. In all probability the progression of the disease by that route was slow and intermittent, if only because the land in question was sparsely populated and transmission would have likewise been slow. But historians do know that once the Europeans began to settle in North America (Jamestown, the first permanent British settlement in North America, was established in 1607), malaria followed, and that the impact of malaria in North America was greatly exacerbated by the slave trade.

Malaria was rife in Europe during the 17th century. Moreover, the type of malaria that was common was the derivative produced by exposure to Plasmodium falciparum, the more virulent form of the disease. In England, a variety of steps were undertaken to stem the tide of disease. One of these actions was the draining of coastal swamps, which were viewed as the source of disease-causing miasmas, although the connection to mosquitoes and Plasmodia was yet unknown. Unfortunately, this action actually made the problem worse. Coastal areas were periodically flooded by salt water from the North Sea. This action washed the mosquito larvae that cause malaria out to sea making the problem less severe than it would otherwise be. However, when the swamps were drained, full scale flooding by sea water was eliminated, leaving only small pools of brackish water in its place. The resulting brackish pools were ideal breeding grounds for mosquitoes. As a result, mortality rates due to malaria peaked every ten years or so at about 20%. Those who tried to flee coastal cities and move inland were often claimed by bubonic plague rather than malaria, which experienced resurgence in England in 1625. It is not surprising that many in Europe would make the choice to seek a new life in a pristine place called the New World as a result of chronic mortal diseases, in addition to political strife that was common in Europe. Sadly, many of the people who left English coastal cities to go to America were carrying malaria with them even as they boarded the ships for the New World. One chronicler noted that the travelers could board a ship in England in good health and be suffering from chills and fevers by the time they landed in Chesapeake Bay. At that point, they would have been infectious, and anyone who came into proximity with the sick Europeans and any hitchhiking mosquitoes would have been vulnerable to the disease.

In the New World, particularly in the area that would become the state of Virginia, conditions had grown ripe for malaria. A significant extended drought hit tidewater Virginia during 1606-1612. This meant, in turn, that small streams that empty into tidal areas dried up, forming small pools—just the type in which mosquitoes like to breed. Further, the clearing of the land by the colonists increased the problem by denuding the land of trees. Mosquitoes grow faster as temperatures increase and, without the shade provided by the trees, the pools in which the mosquitoes bred were at a higher temperature, thus making it possible for more generations of mosquitoes to be produced in a single season. With malaria-laden hosts arriving from Europe potentially with every ship that came into port, the conditions were ideal for an outbreak of malaria in the New World. And, while we do not know the date of the initial onset of malaria in North America, it is clear that once the colonists arrived, malaria quickly followed.

The incidence of malaria among the transplanted colonists was so common that it became a course of chronic complaint. Clearly, the work of establishing the colonies required a healthy labor force. However, it was well known that newly arrived people from England were of little help until they underwent a year of “seasoning.” This likely was the time during which they were fighting off malaria that they either contracted in England or, as time went on, in the New World upon arrival. If the colonists were lucky, they would be severely incapacitated for many months, but would recover. About one third of the people who contracted malaria were not lucky and died of the disease. Even in the historically revered Jamestown, about one third of the new arrivals died for the first fifty years of its existence.

Nonetheless, having made the decision to uproot their families and invest all of their money in the trip to the New World, the colonists were determined to make a go of it. One critical issue that had to be resolved in order to secure success was how to make money in the New World without an established economy. What could the colonists do to make money? Preferably, it would entail something that they could sell back in Europe where people still had money to buy things. The building of productive cities and expansion of the colonial footprint in North America depended upon finding a reliable source of goods that could be traded. The Chesapeake Bay had no gold or silver. It also lacked the abundance of animal life that supported the valuable fur trade further north in America. Ultimately, the colonists in Virginia decided that investing in tobacco production, a product with high appeal in Europe, and therefore likely to be profitable, made sense.

Economically, tobacco farming seemed like a good investment in a fledgling economy. But, getting started in the New World was not easy. Remember, the colonists arrived in a place that was basically a wilderness. To cultivate tobacco, the land had to be cleared of trees, which is arduous work. One has to chop the trees down, drag them from the site and cut them up. Of course, the trees would then have another function as firewood. But, without mechanized equipment, it is back-breaking work.

Next, much of the coastal land was swamp. In order to be good farmland, the swamps had to be drained and tiled to prevent further inundation by water. Next, the land had to plowed, fertilized, and sown. Once the crop came up, it had to be weeded and tended. Horse-drawn implements were very helpful in these endeavors but it was still a time-consuming task that required good weather and a strong back to execute. Finally, once the crop was ready to harvest, a whole new set of labor-intensive activities became necessary, such as cutting and curing the tobacco. Then, the dried tobacco had to be packaged into large bales and loaded onto ships. This is not something that could be done easily by a small number of men if tobacco was to be grown on a scale that would provide capital for economic growth. An ancillary labor force was needed.

Indentured Servitude & Malaria

At this point, the colonists had basically two choices for securing the needed labor in the timeframe they had, and at a price that was affordable. One possibility was to hire indentured servants from Europe. These were contract-laborers who didn’t have sufficient funds to get to the New World on their own. In return for their labor, guaranteed for a 4–7 year period, their travel was paid for as well as their living expenses during the term of their servitude. At the end of their service, the laborer was released to find his own way of making a living.

The other option open to the colonists was to import slaves—a form of coerced labor in which the slave never has the right to leave unless the owner frees him. The American form of slavery was the most draconian type. The colonists practiced chattel slavery in which the owner had complete authority over the life, labor, and liberty of another human being in perpetuity. It was a life sentence under extremely abusive conditions.

While subjugating another human being and forcing him to work for free may seem to make sense economically on the surface (despite the extreme moral depravity of the situation), according to economist Adam Smith, this is untrue. Smith calculated that the cost of an indentured servant was $10 whereas the cost of a slave (most likely from Africa) was $25.

But the cost differential was not the only issue. Indentured servitude is entered into voluntarily by both parties and there is a contractual end date after which the contract is fulfilled and the indentured servant is released. In contrast, slavery is the involuntary appropriation of another’s labor without end. Those who were held as slaves were viewed as liabilities because they all had strong motivation to flee if possible. Some owners feared that their slaves would rise up and kill them. Add to that the fact that slaves stolen from Africa probably did not speak English and had different social mores from white Europeans. As a result, it would be both hard to communicate and understand the thinking and motivations of the other party in the relationship of European master and African chattel slave. Indentured servants had none of these problems.

A final factor of influence was the low interest in slavery in England at the time the colonists were cultivating the new world. This was in part due to the fact that the British were still reacting to the imprisonment of British citizens by Barbary Pirates. The Barbary Pirates fueled trafficking of white, Christian European slaves by attacking ships loaded with Europeans in the coastal areas of Europe. The pirates took and enslaved men, women, and children. So numerous were people extracted from seafaring vessels and forced into slavery that populations declined by as much as 50% in some coastal cities. Unemployment of Brits was also very high at the time, meaning that there were a lot of people willing to work as indentured servants and making slavery even more unpopular. So, why did the colonists opt for the more expensive and morally repugnant slavery over a cheaper form of labor?

The truth is that the colonists initially preferred indentured servants as workers. Somewhere between 35–50% of the first immigrants to North America were white indentured servants. In Virginia, there were only 300 African slaves in the entire territory by 1650. However, by 1700, as many as 16,000 slaves were in service in Virginia and the number kept growing thereafter. The area that would become the southern United States was developing as a slave-holding society. The question is, given the negative aspects of using slave labor, why did this happen?

The answer is complicated. Part of it relates to climatic conditions in Europe during the time in question. Europe was undergoing what became known as “The Little Ice Age.” The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) defines the Little Ice Age as an unusually cold period between 1550 and 1850 AD. During these three centuries, there were three particularly cold periods beginning in 1650, 1770, and 1850 respectively. There were warm interludes between the cold periods. However, during the repeated cold periods, ice began to form on rivers and streams in England and glaciers began to advance across farm land in villages in the Swiss Alps. The cold caused massive crop failures leading to hunger and starvation on a broad scale. Those who could leave did so.

Between 1650-1680, England’s population declined by 10% due to emigration in an attempt to outrun the cold weather. The short supply of labor in England drove up the cost of labor, making indentured servants more expensive. The colonists in the New World, thus, began to seek alternatives to indentured servants.

Clearly, the rising costs of procuring indentured servants in England motivated the colonists to look at slavery as a cheaper alternative. But, it is still unclear why the colonists chose African slaves when there would have been other alternatives among European countries. The Little Ice Age ravaged crops from Scotland to Norway. Starvation was rampant. Why choose African slaves when relative inexpensive European labor could have been procured from Ireland and Scotland in the form of indentured servants?

The answer to this apparent conundrum could be malaria. The historical record shows that 1,400 impoverished Scotsmen decided to escape the ravages of a wretched economy at home by journeying to, of all places, Panama. The emigrants were sold on the idea that they could become rich by tapping into the Panamanian trade in silk and silver. However, shortly after their arrival in South America, the Scots were stricken by malaria. The 300 survivors returned to Scotland within 8 months.

The take home message from the Scots’ misadventure in Panama was that Europeans were too susceptible to malaria to be good workers. Clearly, this impression was reinforced by the near obligatory “seasoning” that the colonists themselves typically underwent upon arrival in the New World. As a result, a European labor force was not an attractive proposition if the goal was to find cheap, reliable labor. Individuals still opted to set sail from Europe to North America as a means of escaping a bad economy as well as political and religious oppression. However, the idea of importing large numbers of Europeans to constitute a labor force was not attractive because of malaria. The collective decision of the American colonists was to look elsewhere for the means to staff their farms and houses.

Indigenous Slavery & Malaria

At the same time, other forces of importance were coming into play. For instance, in 1670, the colony of Carolina was formed to the south of the colony started in Virginia. Both were conceived of as commercial enterprises that were underwritten by European nobles who were hoping to become very rich without investing much in the way of their own time or money. Coincidently, the Carolina colony was established at the same time the flintlock rifle became available and wars among different tribes of indigenous people in the area were causing great instability. The hostilities among the indigenous tribes also spilled over into the relationship with the Europeans.

Among tribes of indigenous people in the Americas, slavery was a fairly normal practice. However, it was not the chattel slavery practiced by white Europeans in America. Rather, slaves were taken as prisoners of war by warring tribes. The prisoners might be pressed into service for a time but were ultimately released, traded, or killed. A new opportunity opened up with the arrival of Europeans with money. And this entailed selling captured indigenous slaves to the Europeans in exchange for flintlock rifles, which greatly increased their ability to defend their own tribes and exact retribution on other tribes. As a result of this newfound, highly valued commodity, the indigenous slave trade was born in America. The numbers attest to its immediate success: by 1708 there were 4,000 European colonists in Carolina, 1,500 indigenous slaves, and 160 indentured servants.

During the years between 1670 and 1720, up to 50,000 indigenous slaves were captured or purchased by the white settlers in Carolina and largely exported to other places, such as Virginia, to support the growing tobacco industry. Interestingly, the indigenous slaves were taken primarily from the Mississippian tribes, which were the predominate ethnicity in southern U.S. In the northern colonies, the indigenous people who cohabited the land with settlers were from the Algonkian tribes. The latter did not have a practice of slavery. As a result, there was a dichotomy in the slave trade between northern and southern colonies whose boundary was in the Chesapeake Bay area near what would become the Mason-Dixon line later in American history. Thus, what began as a seemingly minor difference in the early years of European settlement on the North American continent would become a defining moment and a source of travail for the U.S. for centuries to come.

Given the initial success of the establishment of the tribal slave trade in the southern colonies, it is a matter of some curiosity that it disappeared by 1715. Again, one has to ask why? The imperative to have a cheap, reliable labor force had not disappeared. In fact, the need for such labor increased as the success of various industries and businesses grew. It was at this point that one of the unforeseen results, albeit in retrospect somewhat obvious, of arming the indigenous people with flintlock rifles would emerge.

The increased need for cheap labor as southern industries grew required more slaves. Thus, business people pushed tribes to provide more slaves, and this fueled increased strife and further destabilized indigenous societies. Among the tribes, all sides were interested in securing more money and rifles from the Europeans. At some point, the tribes, now armed to the teeth with rifles began attacking the colonists. Adding to the problem was the reality that the tribes knew the geographical terrain much better than the colonists making it difficult to know when or how they would be attacked. At this point, the colonists’ interest in indigenous slaves fell precipitously. And, turning to the northern colonies for slaves wasn’t an option because the slave trade was not well developed in the north.

Even with these difficulties, it appears that the pivotal factor in the demise of the southern indigenous slave trade was not munitions but malaria yet again. Initially, the word about the southern colonies that reached Europe was highly favorable. The southern climate was hailed by the founding settlers as showing “no distempers either epidemical or moral.” That description turned out to be short-lived and the critical element in changing the view of the Europeans in the Carolinas was accomplished by their own hands. The colonists made the critical decision to grow rice, a crop which requires flooding the fields with standing water for a good part of the life cycle. This, of course, would prove to be very attractive to mosquitoes and, as one can guess, malaria would not be far behind. From the descriptions of the fevers that ensued, it appears that not only did Plasmodium falciparum arrive with the gift of malaria, but yellow fever, also vectored by mosquitoes, as well.

Whatever fantasies the colonists had about the Carolinas being a Garden of Eden rapidly disappeared along with their labor force. The indigenous slaves had not been exposed to malaria before and were, therefore, highly susceptible. As a result, they died in large numbers, leaving the European survivors to once again contemplate how to procure a cheap, reliable source of labor to support their fledgling industries. Now informed by 50 years of experience with indentured servants and indigenous slaves, a new source of labor that lacked the difficulties of the previous forms was sought. And this time, the hallmark characteristic of the ideal worker included low susceptibility to malaria.

African Slavery & Immunity

The attention of the southern colonists turned to the African continent at this point. Unbeknownst to them, they were making a decision that would stem the tide of death due to malaria among their labor force. It is at this point that biology becomes highly relevant, and there are two aspects of the biology of malaria in humans that are critical to understanding why this decision was so important—even though the colonists had absolutely no understanding of genetics or the biology of malaria.

The first key biological factor among West African natives, the primary source of chattel slaves for the colonists, lack the Duffy antigen. The Duffy antigen is one of many small sugars that sits on the outside of red blood cells (RBCs) and helps to regulate traffic of small molecules in and out of the cell. The Duffy antigen has a binding spot that has a very specific shape. Only things that have a complementary shape (like a lock and key) can bind to the antigen. Chemicals or entities with a complementary shape can bind to the antigen and use it as a portal to enter the RBC. It turns out that Plasmodium vivax, the causal agent of the second form of human malaria, can bind to the Duffy antigen and enter human RBCs. This is how the malarial infection of the red blood cells is initiated. However, since 97% of the natives of West African descent LACK the Duffy antigen, P. vivax can’t enter their RBCs, and they are, therefore, resistant to that form of malaria. The trait for having the Duffy antigen is genetically conferred. Since the trait is lacking in most West Africans, it means that parents who lack the antigen will produce children who also lack the antigen and they all will be resistant to the P. vivax form of malaria.

Another interesting aspect of malaria biology is that resistance to P. vivax among West Africans due to the lack of a Duffy antigen also confers approximately 50% resistance to malaria caused by P. falciparum. Importantly, this form of resistance to P. falciparum is distinct from the acquired resistance that some European colonists enjoyed as a result of having survived malaria. The latter is not genetically determined and, thus, will not be passed from parent to offspring. However, the partial resistance of West Africans who lack the Duffy antigen is genetic and will, therefore, be passed to offspring making the children of such parents fully immune to P. vivax and partially protected from P. falciparum. In the scheme of things, it was a huge step forward to have a labor force with these characteristics. Not only could West African slaves who were relatively free of malaria put in a full day of work, but they could produce children who were likewise resistant to malaria. From a strictly economic standpoint (morality aside), seeking West African slaves clearly made financial sense.

An additional aspect of the various forms of malaria now becomes relevant. Despite the financial benefits of importing African slaves, there was a downside specifically for European colonists. Europe has a relatively colder climate than western Africa. As a result, the form of malaria found in most of Europe is P. vivax, which has a wider temperature tolerance than P. falciparum. As a result, when the European colonists began to import west African slaves, the colonists were potentially exposing themselves to a form of malaria to which they had no previous exposure and, hence, no acquired immunity. In addition, P. falciparum also causes the form of malaria that is most deadly among humans. Contracting malaria caused by P. falciparum also would have increased because of the warm southern climate and the aforementioned changes to the environment, such as clearing the land and cultivating rice. As a result, a lot more southern colonists probably died of malaria than would have happened if they had not imported African slaves. And that may be a form of biologically-based poetic justice.

Sickle Cell Anemia & Malaria

There is a final aspect of human genetics and malaria biology that made the importation of West African slaves particularly advantageous from a fiscal point of view. This is the relationship between another dread disease, sickle cell anemia, and malaria. Sickle cell anemia (also known as sickle cell disease or SCD) is a terrible disease that results in death at an early age when present. The term “sickle” refers to the half moon, or sickled shape of the resulting blood cells rather than oval shape of normal blood cells (Figure 14.1). It is also genetically determined. Hemoglobin, the protein that binds oxygen and allows us to breathe, is the product of a single gene. But, the gene exists in two forms, or alleles. The normal, dominant allele of the gene produces normal functional hemoglobin. However, the other, mutated allele of the gene produces abnormal hemoglobin that results in sickled red blood cells which do not bind oxygen effectively.

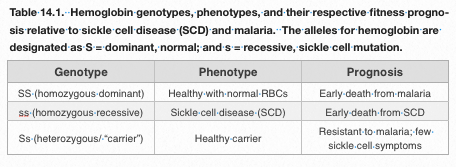

Fortunately, the sickle cell trait is recessive: an individual has to have two copies (alleles) of the recessive gene to have the disease. Because of the fact that the gene for sickle cell anemia is recessive, there are three potential genotypes of individuals AND the health status (phenotype) of all three types is significantly different. Individuals with two copies of the normal allele (homozygous dominant) will have normal hemoglobin. Individuals with two copies of the mutant allele (homozygous recessive) will have sickle cell anemia. Finally, some individuals have one dominant allele and one recessive allele, and are heterozygotes (also called “carriers”) of the conditions—meaning they don’t express the trait, but can pass on either the dominant or recessive allele to their offspring. With respect to binding oxygen, the heterozygote individuals are able to breathe normally because they have one copy of the normal gene, and that usually is sufficient to allow them to live normally and have a normal lifespan.

The prevalence of sickle cell anemia is comparatively high in people of African descent. About one in 500 people of African descent have two copies of the recessive trait and, therefore, have the disease. About one in every eleven people of African descent are are heterozygotes. In the United States, the prevalence of sickle cell anemia is approximately one in 3,200 people.

Because sickle cell anemia is a condition that results from a defect in a single gene, it has been widely studied and we now know quite a lot about the specific details of how the disease is produced. Interestingly, a single DNA nucleotide has been replaced in the DNA that leads to the production of sickle cell anemia. Normal DNA that is disease-free has a 3-membered DNA triplet, or codon, that reads CTT. When the DNA is transcribed and translated to produce the protein we know as hemoglobin, the amino acid glutamate will be inserted into the hemoglobin molecule at that point. However, in the case of sickle cell anemia, a mistake was made in copying the DNA. So, now instead of having a CTT codon, the middle T (thymine) has been replaced by an A (adenine) and the resulting DNA codon reads CAT. When the resulting DNA is rendered into the hemoglobin protein, the wrong amino acid, in this case, valine, is inserted in the hemoglobin protein instead of glutamate. And although this is just one of the 300 or so amino acids that make up the hemoglobin molecule, it is enough to change the resulting hemoglobin into a protein that does not bind oxygen effectively.

The abnormal hemoglobin found in individuals with the mutant allele has impacts at multiple levels in the human body. The sickling is caused by the fact that the abnormal hemoglobin crystalizes, causing the red blood cell to cave in on itself, or sickle. The abnormal hemoglobin does not bind oxygen well, as previously discussed. However, this is just the beginning of the problems. The sickled cells are more likely to break down, potentially leading to anemia, physical weakness, and heart failure. The sickled cells also stick to each other and can clump together clogging smaller blood vessels (refer back to Figure 14.1). This can result in pervasive pain and, eventually, organ failure. Finally, accumulation of sickled blood cells in the spleen can lead to splenic failure, from which a host of other problems can flow. In short, sickle cell anemia is a problem with a simple origin: a single base substitution in a gene. And yet, the effect is widespread within the human body and highly pernicious.

But how is this related to malaria? To make sense of this, we have to understand that the environment, as well as the underlying genetic instructions of individual genotypes, interact to produce genetic success or failure. In the context of Africa, where malaria has been endemic for millennia, survival of the three human genotypes of the hemoglobin gene is distinctly different. Homozygous dominant individuals will have normal hemoglobin, which will not limit their survival. However, these individuals can expect to be exposed to malaria sometime during the time they live in Africa and, therefore, will potentially die of malaria. The homozygous recessive individuals (two copies of the mutant allele for hemoglobin) will have sickle cell anemia and can expect to die at an early age from the disease. Finally, the heterozygotes, with one copy of the normal hemoglobin allele and one copy of the mutant allele, will have normal oxygen binding capacity and, it turns out, will be resistant to malaria. As a result, the heterozygote is more likely to survive and reproduce than either the homozygous dominant or homozygous recessive individual. A summary of the genotypes and phenotypes as well as their respective fates appears in Table 14.1.

We don’t know why the sickle cell gene confers resistance to malaria. But it is clear that individuals with one copy of the sickle cell gene fare better in environments ridden with malaria. There are other cases in which the heterozygote for a particular trait is seen to have superior fitness. We call this hybrid vigor. The important point to take here is that success of the genotype (or lack of it) is realized in the context of specific environmental influences. When malaria present, having one copy of the gene for sickle cell anemia is a decided benefit.

A final note of biological interest is that normally, because it is a lethal disease, we would expect for selective pressure against the gene for sickle cell anemia to be so high that eventually the defective allele would disappear from the human population. Since it’s victims typically die before the age of reproduction, the mutant allele should be less commonly passed on to offspring, and the trait should decline in prevalence and eventually disappear, if it followed the typical course of such alleles. However, the high biological fitness of the carriers of the sickle cell trait means that the allele will be maintained in the human population due to the success of the heterozygotes. Only if malaria were eradicated would the success of the heterozygote cease to play a role in maintaining an otherwise defective allele in the human population.

Using modern malaria data from Africa (Figure 14.2a-c – click on link), one can see that malaria is rife in Africa and Asia (Figure 14.2c). This is not new information. Even comparing Africa with Asia, the levels of malaria (indicated by more of the very dark green color) is much higher in Africa today. But what is interesting about this figure is the prevalence of the sickle cell trait. In Western and Central Africa, as much as 19% of the population are carriers of the sickle cell trait in modern times (Figure 14.2b). These data effectively make the case that the protection against malaria afforded by harboring one copy of the allele for sickle cell anemia has maintained the allele for a very lethal disease in the people of West African descent. This high prevalence of the sickle cell allele is not seen in other areas afflicted by levels of malaria that are lower than in Africa.

Chapter Summary

Returning now to the European colonists who were seeking a source of affordable labor, the choice to import West African slaves appears propitious. Unbeknownst to the colonists, many Africans would have genetically-determined immunity as a result of having lacking the Duffy antigen. A significant percentage of the West Africans would also carry one copy of the sickle cell allele and have a further source of genetic resistance to malaria. When brought to America, the newly arrived slaves would have probably not undergone the “seasoning” that the Europeans experienced. Indeed, mortality data from the time showed distinct patterns with respect to European and African mortality.

African deaths in the winter and spring months were higher than that among Europeans. But, malaria was less important a factor in those deaths than generally poor living conditions that begat illnesses such as dysentery and tuberculosis. Combined with maltreatment and poor nutrition, many Africans did not survive. But the mortality curves of the Europeans increased greatly in the late summer and fall, which corresponds to peak mosquito season. Death among Europeans to malaria, thus, increased during those months and eclipsed that of the imported Africans who were protected from malaria and, therefore, relatively resistant. Another datum that supports this conclusion comes from the experience of British soldiers who invaded Africa during this time period. Once in Africa, the British were highly susceptible to P. falciparum, to which they had not been exposed in Europe, nor did they have genetic immunity. As a consequence, the death rate among the British invaders due to malaria was as high as 47%. Among the African natives, the death rate from malaria was approximately 3%. Thus, the genetic protection enjoyed by the West African population against both forms of malaria appears to have made them particularly valuable for the slave trade in North America in a time of rampant malaria.

In the end, biology and economics combined to encourage enterprising colonists to seek West African slaves to staff the fledgling industries in the New World. In what would become the southern United States, slavery and Plasmodium falciparum thrived together. Malaria was a fact of life that the colonists could not eradicate. But, it was possible to secure a labor force that was less affected by the ravages of malaria. And, without knowing anything about the underlying biology or genetics, they hit upon an effective solution: the importation of West African slaves. In the north, it was too cold for P. faliciparum to survive, and northerners were, thus, spared experiencing the more lethal form of malaria. It is with irony that we note that the geographic dividing line for P. falciparum survival is roughly the same as the Mason-Dixon line.

It is also important to note that malaria did not cause slavery. At its most basic level, importation of West African slaves was an economic decision borne of economic necessity. This is not to excuse the trafficking in human beings as being a legitimate business practice. It is not and has led to the more than 400 year legacy of systemic racism that pervades our nation to this day. In modern times, we recognize it for the morally bankrupt practice that it is. But times, and moral sensibilities, were different 150 years ago.

Despite the immorality of the practice, in the context of colonial America, using African slaves simply made economic sense. Their resistance to malaria made the West Africans the most robust workers the southerners could find. The colonists were not specifically looking to imprison black people. In fact, there were significant cultural reasons, previously discussed, to avoid importing people from other cultures. But, the relatively greater fitness of the West Africans in a time and place where malaria was a significant source of mortality simply made economic sense to them at the time. It was enough of a benefit that it overrode the countervailing arguments against it. The reality is that the colonists would have been just as happy to extract labor from the Irish or the Scots if their immune status had been hardier. But as matters stood, those colonists who used African slaves made more money than those who didn’t. And even Adam Smith could have seen the (strictly economic) logic in that. Again, this is not to excuse their behavior or in any way support the practice of slavery; rather, it is an insight into the motivations behind why such events occurred.

And so one of the defining moments in our history, the use of chattel slaves in the southern United States, is found to be a product of both biology and economics. The impact of this part of our history continues to echo today and often in ways that reveal that ill treatment of others can radiate into the present in ways that are seemingly as intractable as they are unfortunate.

References

Chapter 14 Cover Photo:

Columbus: Public Domain: Library of Congress. Accessed via commons.wikimedia.org

Fly swatter: CC0 Public Domain: Clker-Free-Vector-Images. Accessed via pixabay.com

Figure 14.1: Normal and sickled red blood cells. CC0 Public Domain: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Accessed via https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sickle_cell_01.jpg

Figure 14.2: Sickle cell anemia and malaria. From: Piel, F.B. et al. Global distribution of the sickle cell gene and geographical confirmation of the malaria hypothesis. Nat. Commun. 1:104 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1104 (2010). Accessed via http://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms1104

Table 14.1: Hemoglobin genotypes, phenotypes, and prognosis. Information compiled by S. W. Fisher.

Additional Readings

Mann, Charles C. (2011). “ 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created,” Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 557 pp.

Cook , N.D. (2002). Sickness, Starvation and Death in Early Hispaniola. J. Interdisciplinary History 32: 349-386.