A specialized database—often called a research or library database—allows targeted searching on one or more specific subject areas (i.e., engineering, medicine, Latin American history, etc.), for a specific format (i.e., books, articles, conference proceedings, video, images), or for a specific date range during which the information was published. Those of what specialized databases contain can not be found by Google or Bing.

There are several types of specialized databases, including:

- Bibliographic – details about published works

- Full-text – details plus the complete text of the items

- Multimedia – various types of media, such as images, audio clips, or video excerpts

- Directory – brief, factual information

- Numeric – data sources

- Product – model numbers, descriptions, etc.

- Mixed – a combination of other types, such as multimedia and full-text

Activity: Database Types

When to Use Specialized Databases

Search specialized databases to uncover scholarly information that is not available through a regular web search. Specialized databases are especially helpful if you require a specific format or up-to-date, scholarly information on a specific topic.

Many databases are available both in a free version and in a subscription version. Your affiliation with a subscribing library grants you access to member-based services at no cost to you. For example, using PubMed via OSU Libraries enables a Find It link to help you request an item.

Tip: Free vs. Subscription?

In some cases, the data available in free and subscription versions are the same, but the subscription version provides some sort of added value or enhancement for searching or viewing items.

Database Scope

Information about the specific subject range, format, or date range a particular specialized database covers is called its scope. A specialized database may be narrow or broad in scope, depending on whether it, for instance, contains materials on one or many subject areas.

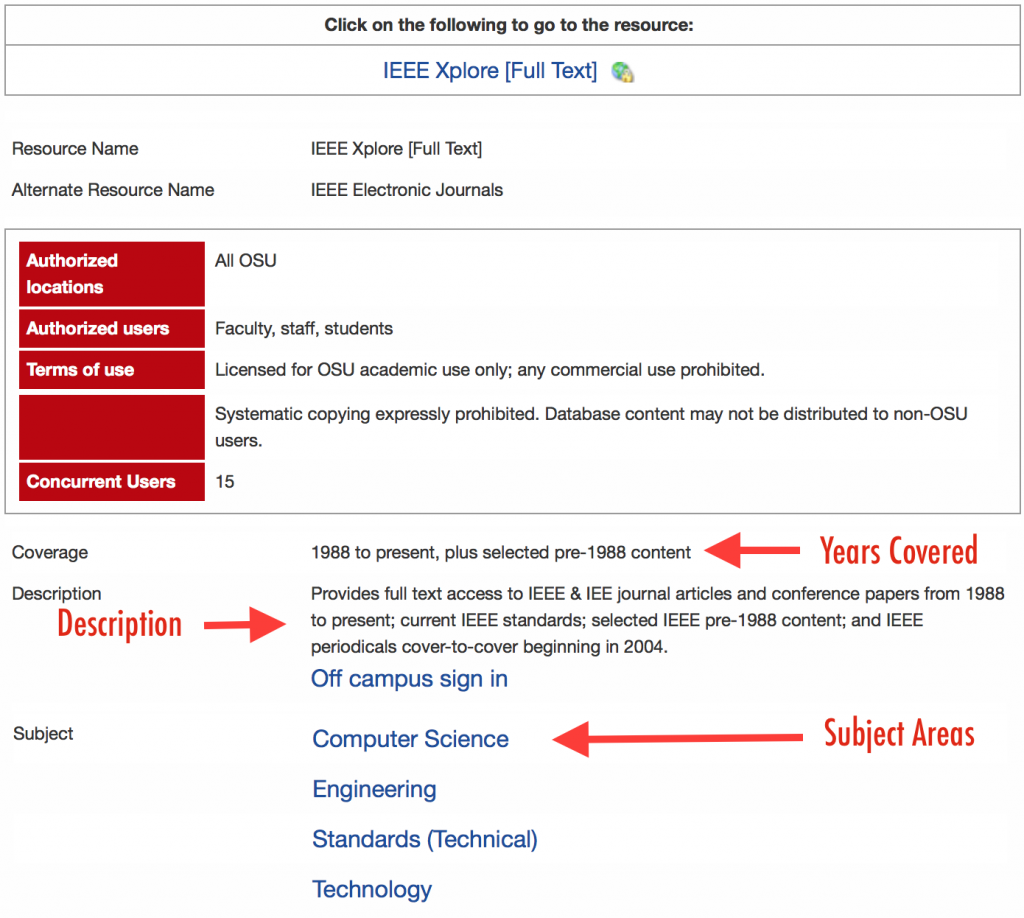

If you are using a database licensed by OSU Libraries and have clicked the title in the list of databases, you will see scope information at the bottom of the same page that says “Click on the following to go to the resource.”

View the live example.

Once you are aware of a database’s scope, you’ll be able to decide whether the database is likely to have what you want (for instance, journal articles as opposed to conference proceedings). Reading about the scope can save you time you would have otherwise wasted searching in databases that do not contain what you need.

Activity: Determining Subject Scope

Activity: Years of Coverage

Instructions: In addition to subject scope, database descriptions should include years of coverage. Visit Ohio State’s Research Databases List to search for the databases listed below. Which database contains the oldest information? Which covers the fewest years?

- Evidence Based Medicine Reviews

- MathSciNet

- GeoRef

Answer to Activity: Years of Coverage

The answer to the “Years of Coverage” Activity above is:

- The database containing the oldest material is GeoRef, which goes back to 1785.

- The database covering the fewest years is Evidence Based Medicine Reviews, which goes back to 1991.

How to Use Them

Use of each database varies somewhat.

See Ohio State’s research database list.

Example: Academic Search Complete

Academic Search Complete (OSU only) is a general article database available through most academic and large public libraries that is often recommended for undergraduate research projects.

Movie: Academic Search Complete Database in 3 Minutes

Keyword Searching

Although keyword search principles apply (as described in Precision Searching), you may want to use fewer search terms since the optimal number of terms is related to database size. Google and Bing work best with several terms since they index billions of web pages and additional terms help narrow the results. Each scholarly database indexes a fraction of that number, so you are less likely to be overwhelmed by results even with one or two keywords than you would be with a search engine.

Phrase searching (putting multiple words in quotes so Google or Bing will know to search them as a phrase) is also less helpful in specialized databases because they are smaller and more focused. Databases are better searched by beginning with only a few general search terms, reviewing your results and, if necessary, limiting them in some logical way. (See Limiting Your Search below.)

Activity: Compare Them!

Instructions:

Compare a search for items containing both phrases “United States” and “female serial killers” in the article database Academic Search Complete (OSU only) and in the web search engine Bing. (Make sure you invlude the quotation makes as they will be searched as phrases.) Notice how searching too narrowly (searching for phrases) affects results in the specialized database. How could you revise the specialized database search to get more results?

Limiting Your Search

Many databases allow you to choose which areas (also called fields) of items to search for your search term(s), based on what you think will turn up documents that are most helpful.

For instance, you may think the items most likely help to you are those whose titles contain your search term(s). In that case, your search would not show you any records for items whose titles do not have your term(s). Or maybe you would want to see only records for items whose abstracts contain the term(s).

When this feature is available, directing your search to particular parts of items, you are said to be able to “limit” your search. You are limiting your search to only item parts that you think will have the biggest pay-off at distinguishing helpful items from unhelpful items.

Searching fields such as title, abstracts, and subject classification often gives helpful items.

Tip: Full-Text Searches

Some databases allow for full-text searching, but this option includes results where a search term appears only once in dozens or more pages. Searching fields such as title, abstracts, and subject classification will often give more relevant items than full-text searching.

Subject Heading Searching

One precision searching technique may be helpful in databases that allow it, and that’s subject heading searching. Subject heading searching can be much more precise than keyword searching, as you are sure to retrieve only your intended concept.

Subject searching is helpful in situations such as:

- There are multiple terms for the same topic you’re interested in (example: cats and felines).

- There are multiple meanings for the same word (example: cookie the food and cookie the computer term).

- There are terms used by professionals and terms used by the general public, including slang or shortened terms (example: flu and influenza).

Here’s how it works:

Database creators work with a defined list of subject headings, which is sometimes called a controlled vocabulary. That means the creators have defined which subject terms are acceptable and assigned only those words to the items it contains. The resulting list of terms is often referred to as a thesaurus. When done thoroughly, a thesaurus will not only list acceptable subject headings, but will also indicate related terms, broader terms and narrower terms for a concept.

Tip: Finding Useful Subject Headings

Try this strategy to find useful subject headings. Remember it by thinking of the letters KISS:

- Keyword-search your topic.

- Identify a relevant item from the results.

- Select subject terms relevant to your topic from that item’s subject heading.

- Search using these subject terms. (Some resources will allow you to simply click on those subject terms to perform a search. Others may require you to copy/paste a subject term[s] into a search and choose a subject field.)

Activity: Searching Specialized Databases

Records and Fields

The information researchers usually see first after searching a database is the “records” for items contained in the database that also match what was asked for by the search.

Each record describes an item that can be retrieved and gives you enough information so that, hopefully, you can decide whether it should meet your information need. The descriptions are in categories that provide different types of information about the item. These categories are called “fields.” Some fields may be empty of information for some items, and the fields that are available depend on the type of database.

Example: Database Fields

A bibliographic database describes items such as articles, books, conference papers, etc. Common fields found in bibliographic database records are:

- Author.

- Title (of book, article, etc.).

- Source title (journal title, conference name, etc.).

- Date.

- Volume/issue.

- Pages.

- Abstract.

- Descriptive or subject terms.

In contrast, a product database record might contain the following fields:

- Product Name.

- Product Code number.

- Color.

- Price.

- Amount in Stock.