2 Chapter 2 -The Exploration into the Impacts of COVID-19 on Learning Management System Usage

Authors:

Megan Dunphy

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a significant shift in how learning took place in K-12 schools across the globe and caused schools to close for short or long periods and open in various stages of online education globally. In the U.S., because K-12 schools shut down for in-person learning, the need for online learning became a necessity.

This chapter will look at how teachers evolved their use of learning management systems to adapt to remote learning because of the pandemic through a survey conducted by our team of 48 school districts in Ohio & six other states. Teachers’ use of technology and learning management systems (LMS) were examined at three points revolving around COVID-19. LMS and remote learning are discussed (1) before COVID-19 (pre-March 2020), (2) during the early period of COVID-19 (March 2020 – June 2020), and (3) during the 2020-2021 school year.

During the early period of COVID-19 (March 2020 – June 2020), teachers greatly increased their reliance on LMS but lacked training and support as well as access to online curriculum materials. Student engagement fell significantly, and parents struggled to help support their learners at home. Once progression was made forward into the second phase of COVID-19 (2020-2021), technology began to adjust to the new learning environments. Teachers adapted technology and educational curriculum to the new hybrid approach. Teachers utilized various LMS to reach both students in person and in a distance learning format.

Our survey showed that the challenges and benefits of remote learning were felt by all involved in education. However, both teachers and administrators rose to this unprecedented experience with accepting attitudes to take on the difficult task of learning new technologies and LMS platforms to best teach their students. In doing so, teachers and administrators worked to provide the best educational experience for students with the resources and knowledge available to them.

Chapter Introduction

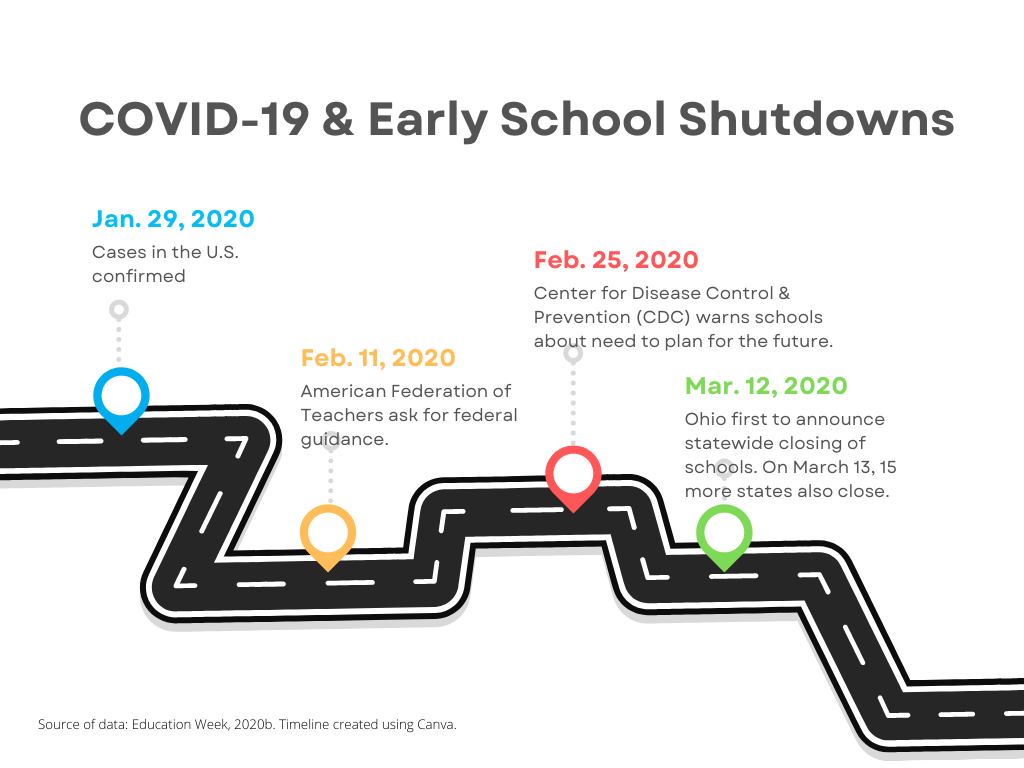

In 2020, the novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused an unprecedented disruption across the globe as businesses, schools, and communities had various strategies to stop the spread of the virus, affecting 1.38 million learners (Li & Lalani, 2020). On March 12, 2020, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine initiated the first statewide school closure with a tweet, “We have a responsibility to save lives. We could have waited to close schools, but based on the advice from health experts, this is the time to do it” (Education Week, 2020b).

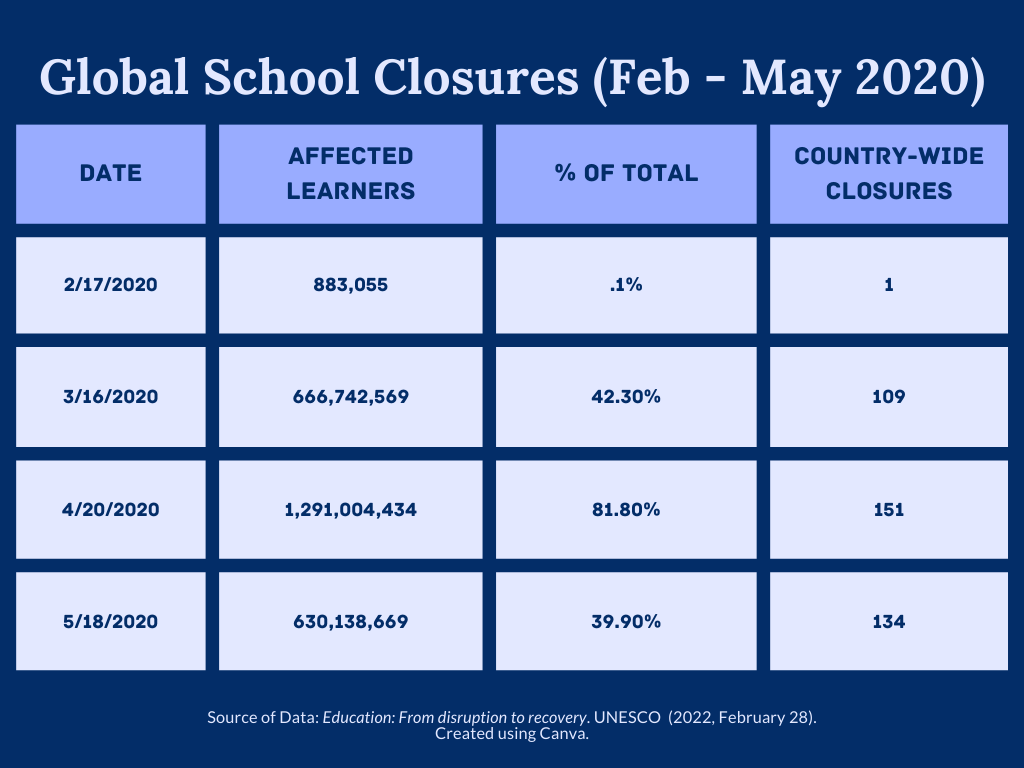

By March 16, 2020, public schools in 27 states and territories in the U.S. shut their doors, and by the end of March, almost 100,000 schools were closed (Education Week, 2020b). An interactive data visualization (Coronavirus Spring – One Each Day -Schools impacted Line Chart) shows the impact of schools closing due to the pandemic. After a few school closures on March 9, 2020, there was a sharp increase between March 11 and March 13, reaching 50,000 schools; from March 15 to March 19, the number rose to almost 100,000 schools and stayed consistent for the rest of the month. Another visualization, “Students Impacted by Coronavirus School Closures,” showed a very similar pattern during March 2020, with a sharp rise in students impacted between March 11 and March 13 (20 million students) and 50 million students affected by March 20 (Education Week, 2020b).

UNESCO tracked the global situation for schools through the COVID-19 pandemic, including the type and duration of school closures (Education: From disruption to recovery, 2022). The website includes an interactive map of “Global monitoring of school closures” and “Total duration of school closures.” In the United States, school shutdowns occurred in almost every state, impacting 50.8 million public school students by April 20, 2020. (Education Week, 2020b; Education: From disruption to recovery, 2022).

With so many schools shut down for the pandemic, online learning became necessary. Worldwide, school districts sought to find ways to use the global educational technology investments that reached US$18.66 billion in 2019 to meet this new demand (Li & Lalani, 2020). Possible challenges included a lack of training and connectivity issues that could be detrimental to learning (Li & Lalani, 2020). In contrast, others saw benefits to a new model of education forced by the need for online instruction (Li & Lalani, 2020). With almost 100,000 schools closed in the U.S. by the end of March 2020 (Education Week, 2020b), school administrators and teachers used online tools and learning management systems (LMS) to meet the needs of affected students (Dindar et al., 2021). With this shift to remote instruction in March 2020, schools needed a way to manage all the online content and student interaction, with many using an LMS. This chapter explores the impacts of COVID-19 on learning management system usage from the teachers’ perspectives. Teachers’ use of learning management systems and how they adapted to remote learning because of the pandemic through a survey conducted by our team of 48 school districts in Ohio and six other states.

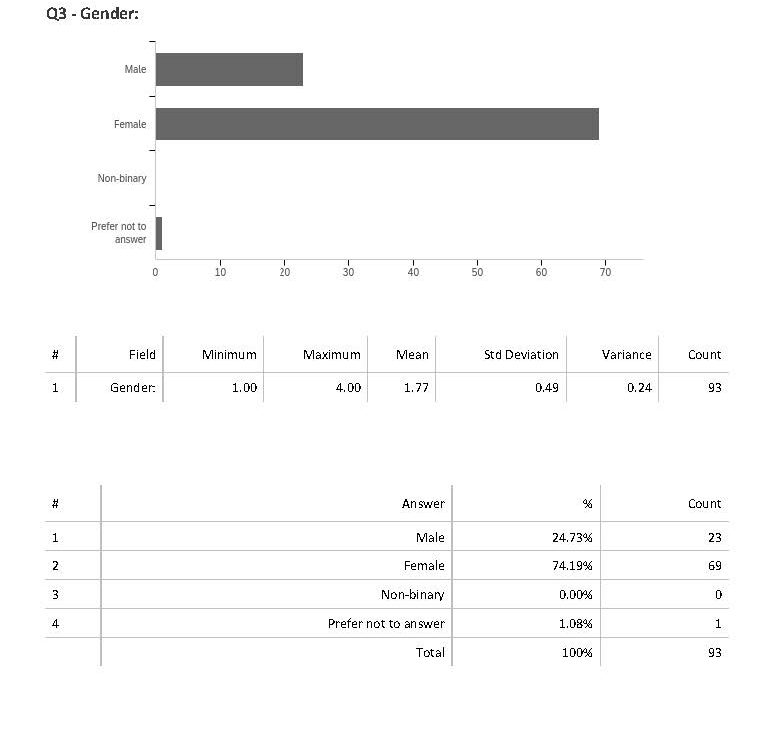

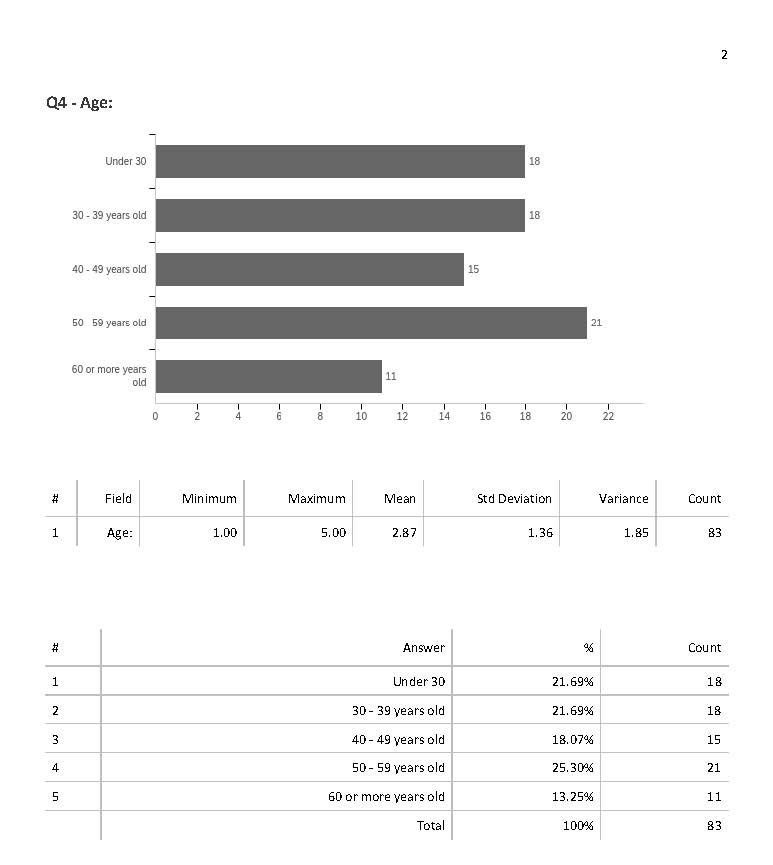

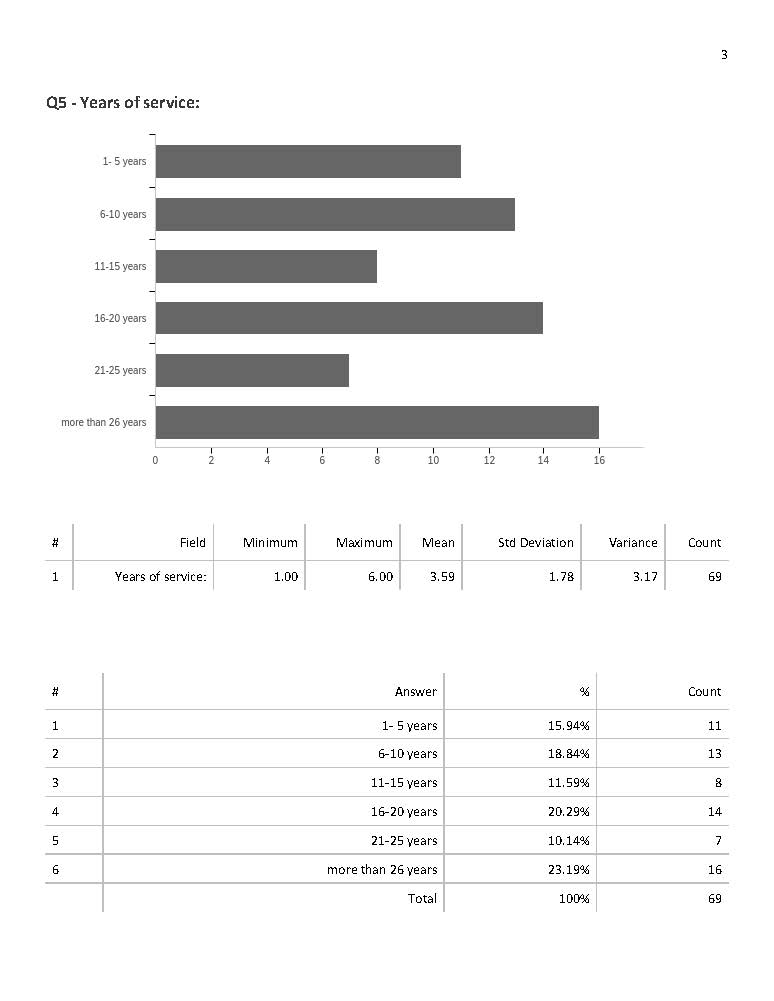

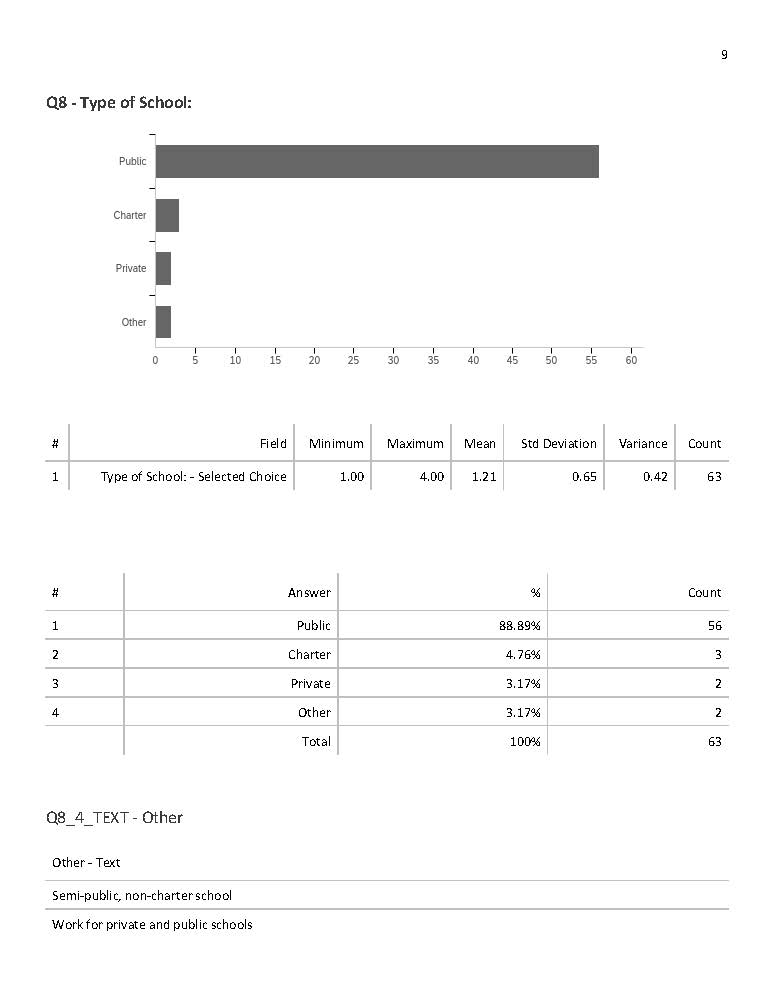

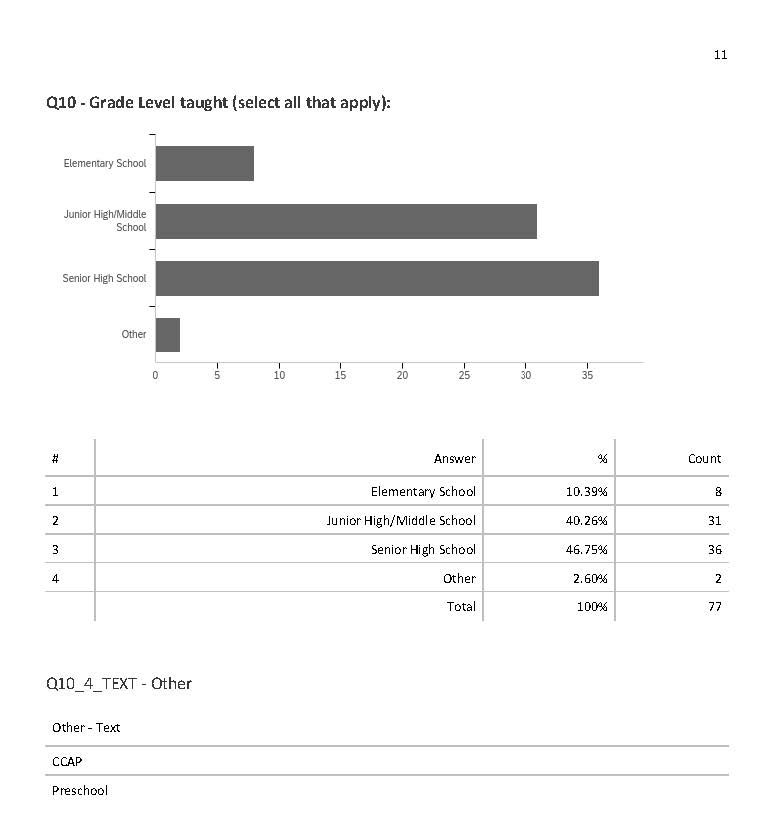

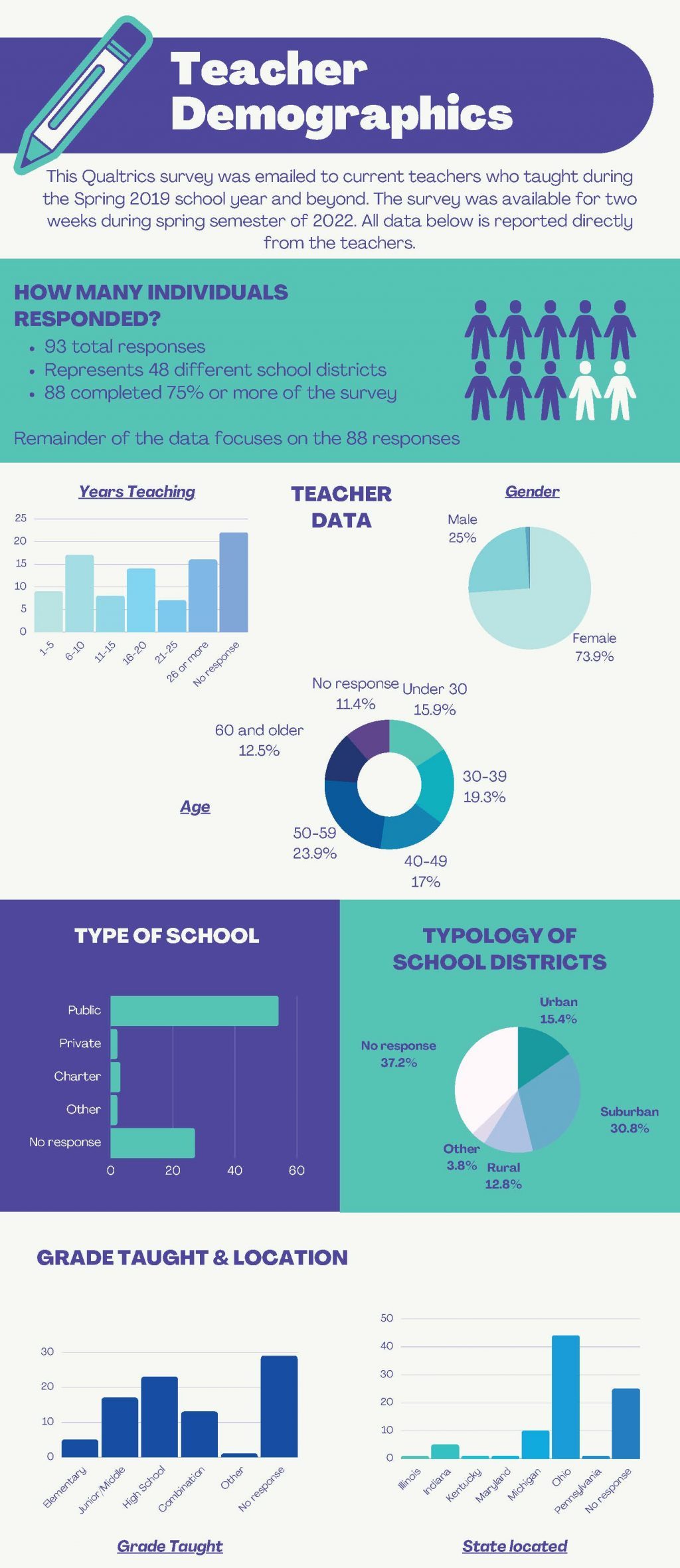

Our team conducted a survey for two weeks (March-April 2022) seeking teachers’ perspectives on their use of technology and learning management systems (LMS) at three points revolving around COVID-19. The survey collected demographic information about the situation before COVID-19 (pre-March 2020) to establish a baseline, information about the early period of COVID-19 (March 2020 – June 2020), and about the next phase of COVID-19 (2020- 2021 school year) regarding the impact on LMS, teaching and remote learning. Team members recruited teachers in several Midwestern states to answer the 32-question Qualtrics survey. Teachers in the survey represented 48 school districts in 7 states (Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania). Data presented throughout this chapter reflected the 88 teachers that completed 75% or more of the survey (see Appendix for full responses).

K-12 Teacher Use of LMS and Technology Before COVID-19

A learning management system (LMS) in school aids instruction by offering more options for face-to-face interaction with students through e-learning environments (Alserhan & Yahaya, 2021). As technology has continually advanced, so have the capabilities of learning management systems and how schools have utilized them. For a global history of LMS, including Sidney Pressey’s teaching machine (1920), SAKI (1956), PLATO (1960), Successmaker (1980), and Sharepoint (2007), please visit the “Learning Management System – Its Journey through time” infographic (Educational Technology Infographics, 2013). Now a LMS serves as “A web-based platform that enables educators to create and deliver online content to students, monitor what students are doing and how they are progressing through customized assessments and assignment completion, and use that information to grade student performance.” (Olson, 2020, p. 2).

Teachers can use the learning management system (LMS) with all stakeholders and encourage communication with students, including discussion and feedback (Olson, 2020). Although teachers have been encouraged to integrate technology into the classroom, limited technology has created some challenges (Dindar et al., 2021). While teachers strive to use technology and digital tools to save time and increase efficiency, training is critical for success (Schoology, 2020).

Learning management systems (LMS) and technology work together. A survey by the National Center for Education Statistics at IES showed the state of technology in schools before COVID-19. About forty-five percent of schools reported having a computer for each student, with 37% more having a laptop for each student in at least some grade levels (Lewis, 2021). Over 70% of schools reported teachers using technology for activities in the classroom to a moderate (47%) or large extent (24%) (Lewis, 2021). Half of the schools in the survey reported that teachers wanted to use technology for teaching, though only about 18% of teachers agreed that training was sufficient (Lewis, 2021). Challenges teachers faced with technology included staying up to date with technology (59% reported moderate or large challenges) and identifying high-quality technology resources to address learning needs (55% reported moderate or large challenges) (Lewis, 2021).

“The State of Digital Learning” report by Schoology looked at the situation before COVID-19 (August – September 2019), found that “Learning management systems are transforming how students learn, how teachers teach, and how institutions as a whole access, share, and store information.” (Schoology, 2020, pg. 4). The report found that “Learning management systems positively impact digital learning and, in turn, student achievement” (Schoology, 2020, p. 7). Of the 16,906 respondents to the survey, 47% used an LMS, though almost 40% more didn’t know if they used one or not. Of those, 35% identified as using Schoology’s LMS. (Schoology, 2020, p. 29).

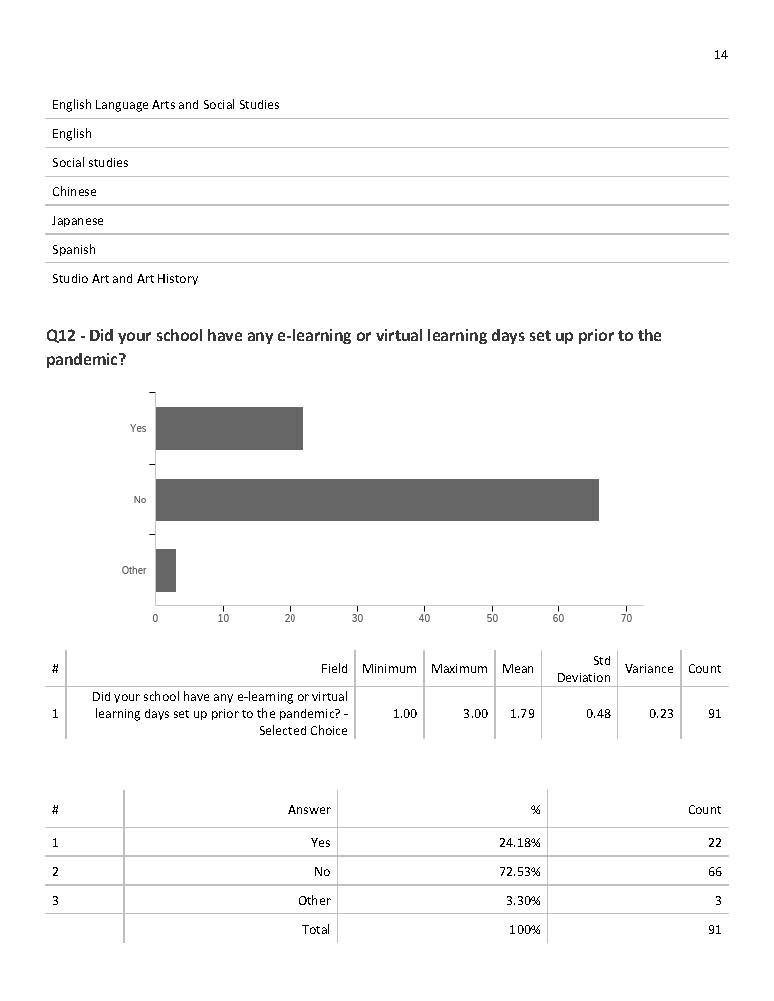

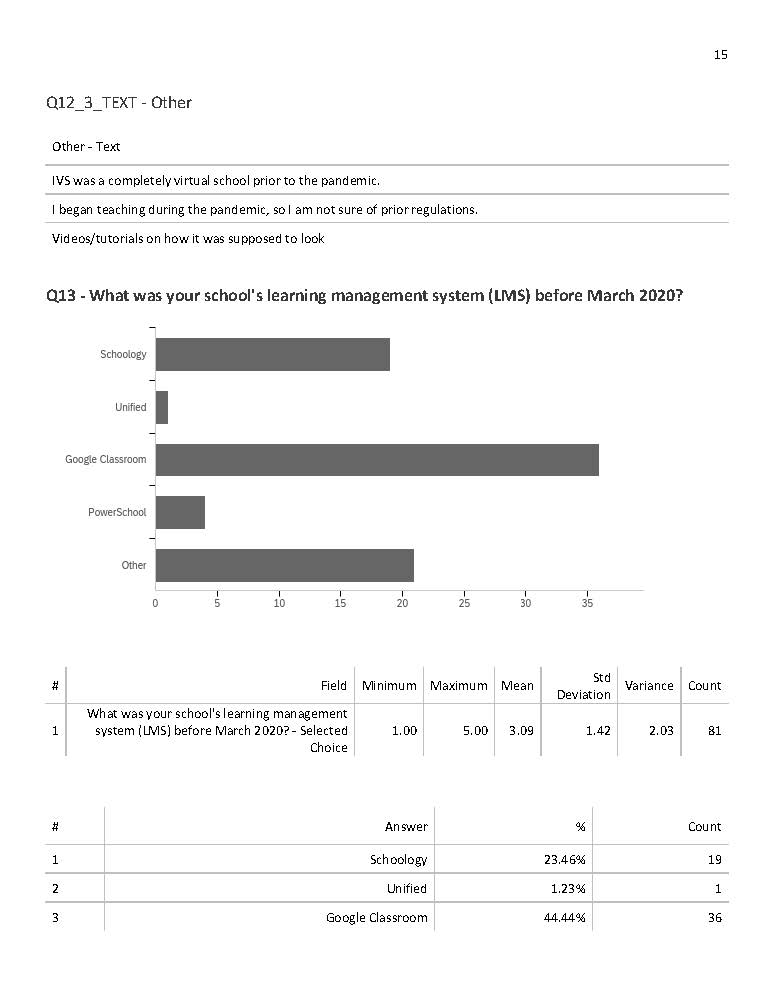

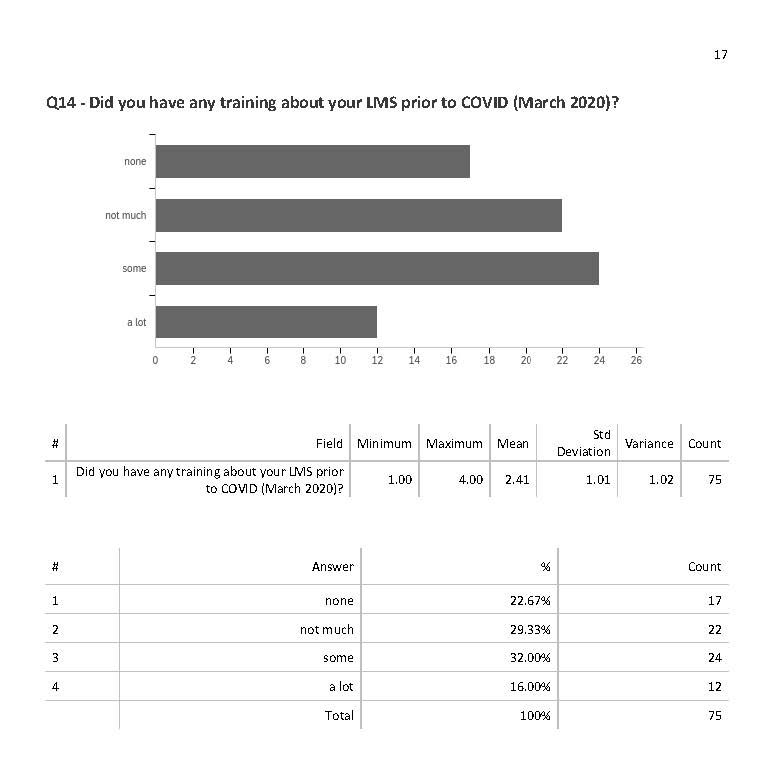

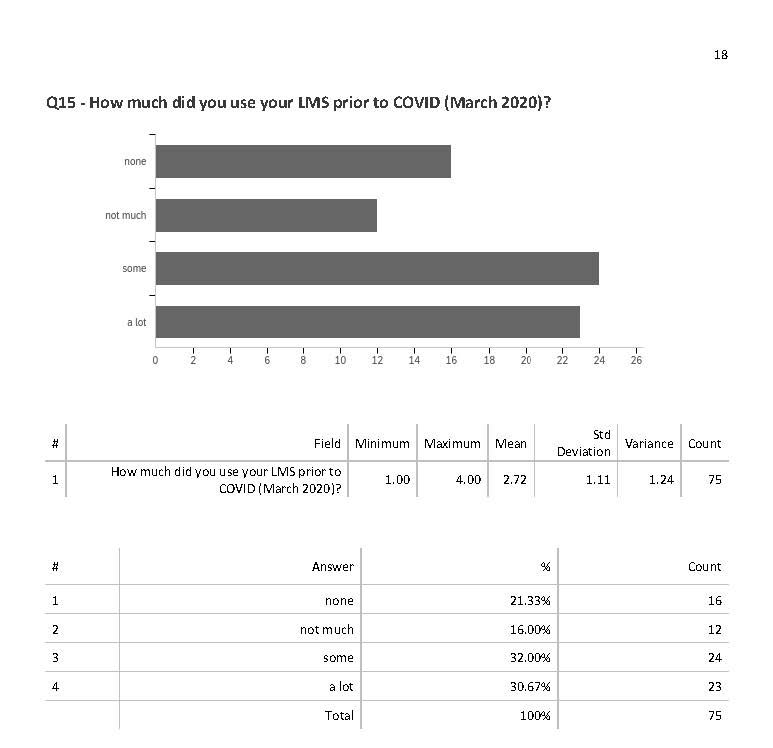

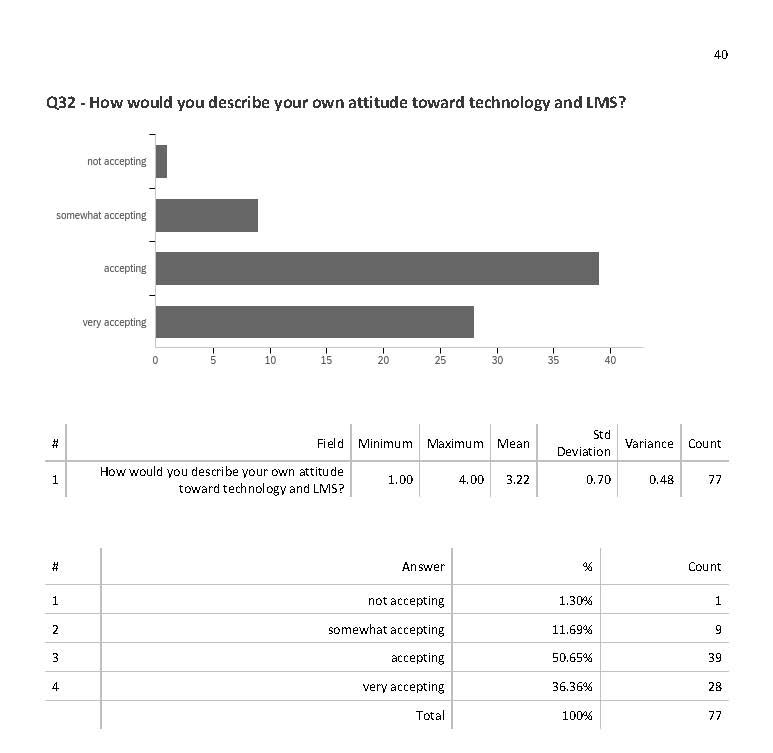

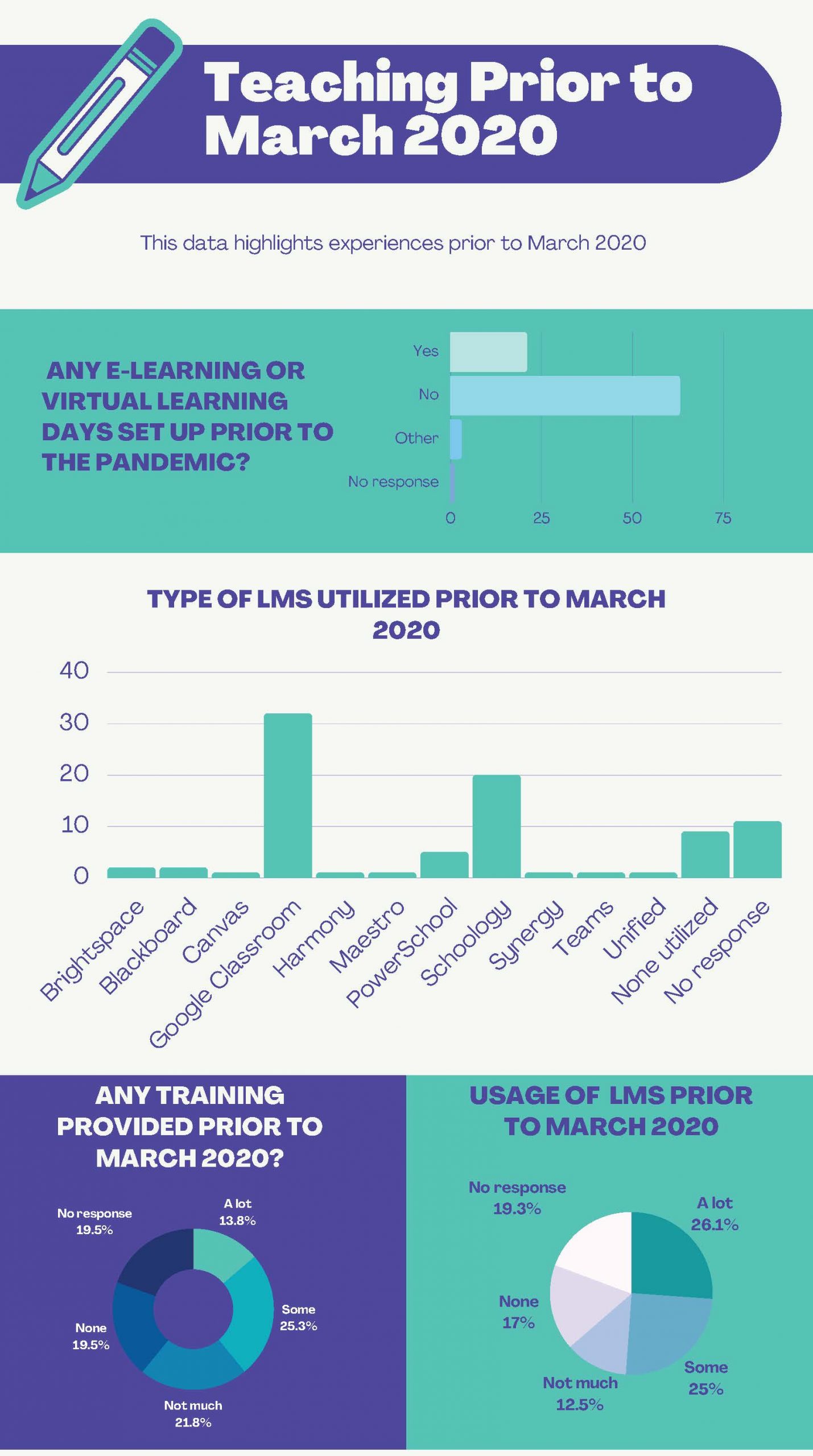

Just as the learning management system varies between school districts, the curriculum materials, including textbooks and digital materials, and supplemental materials used in each school come from many sources and vary widely (Polikoff, 2022). Our survey of teachers in 7 states and 48 school districts in the Midwest found that before COVID-19 (March 2020), 73% of schools did not have an e-learning day (See Appendix). Though not as extensive as the Schoology survey in 2019, our survey also found that 23% of respondents identified using Schoology while 44% used Google Classroom (See Appendix). Also, 52% reported receiving “none” or “not much” training about the LMS. Only 30% reported using their LMS a lot, while 47% reported using the LMS none or not much (See Appendix). The video, Google Classroom vs Schoology: an LMS Comparison, provides more background about the two LMS cited the most by respondents of our survey (Sweeney, 2019).

K-12 Teacher Use of LMS and Technology During COVID-19 Phase I (March 2020 – June 2020)

As previously described in the chapter introduction, COVID-19 first arrived to the United States in late January of 2020, and schools began to rapidly and suddenly close by mid-March. With schools abruptly shut down, teachers were left to figure out how to continue to educate and support their students virtually and from a distance. Francom et al. (2021) describes that while “School closings for localized catastrophic events such as weather events, protests, and disease outbreaks are unfortunately somewhat common… a review of the literature reveals that many K-12 institutions are not prepared for academic continuity in the face of a pandemic” (p. 589-590). Yet, it was crucial for school districts to figure out a way to provide distance learning opportunities for students because school is important to “…help to sustain mental and physical well-being and offer stability and hope for the future” (Francom, et al., 2021, p. 589)

Going into this sudden shift in education, most teachers did not have any e-learning or virtual learning days set up by their school prior to the pandemic (see Appendix). Teachers and students were thrust into the world of distance learning. Polikoff (2022) reminds us of “There were countless news reports early in the pandemic about teachers scrambling to assemble or implement packets of materials or lessons drawn from online lesson-sharing repositories like Teachers Pay Teachers” (p. 5). A video by Education Week, Teaching in the Time of Cornonavirus: Meet the Teachers features teachers from various states discussing the challenges of online learning (Education Week, 2020a).

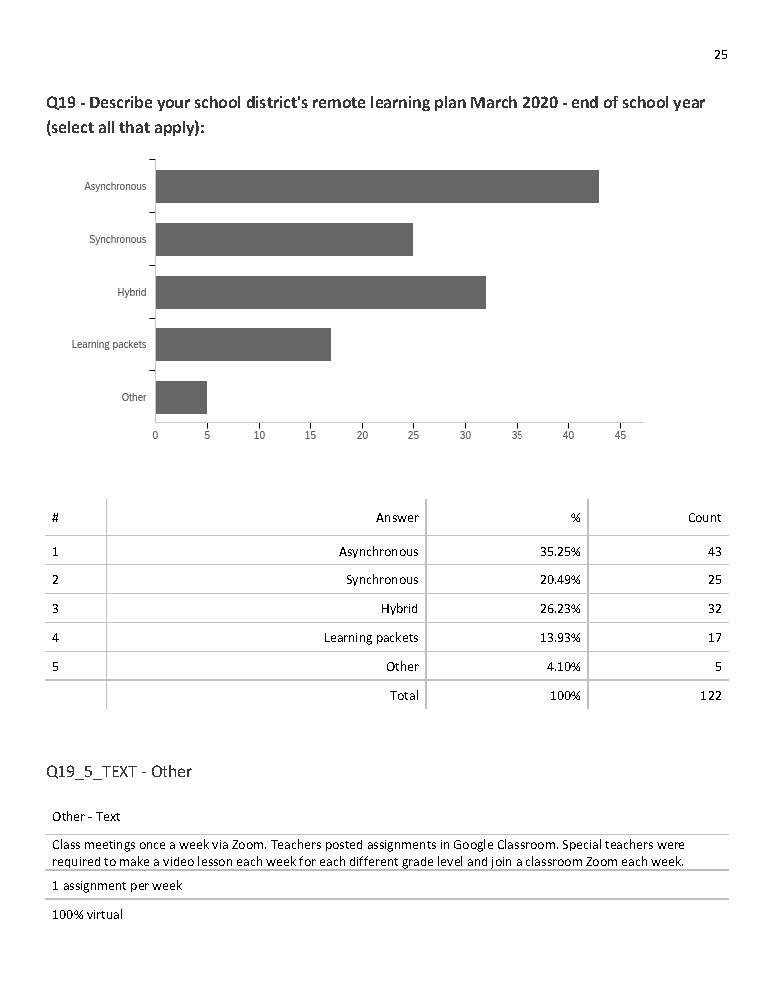

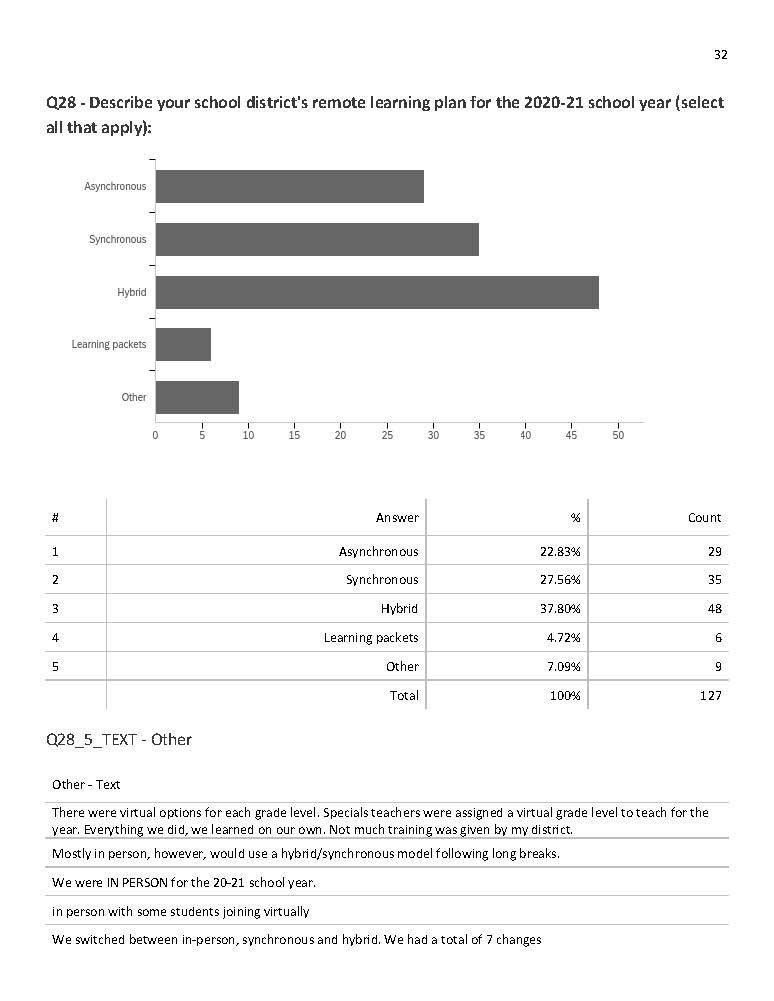

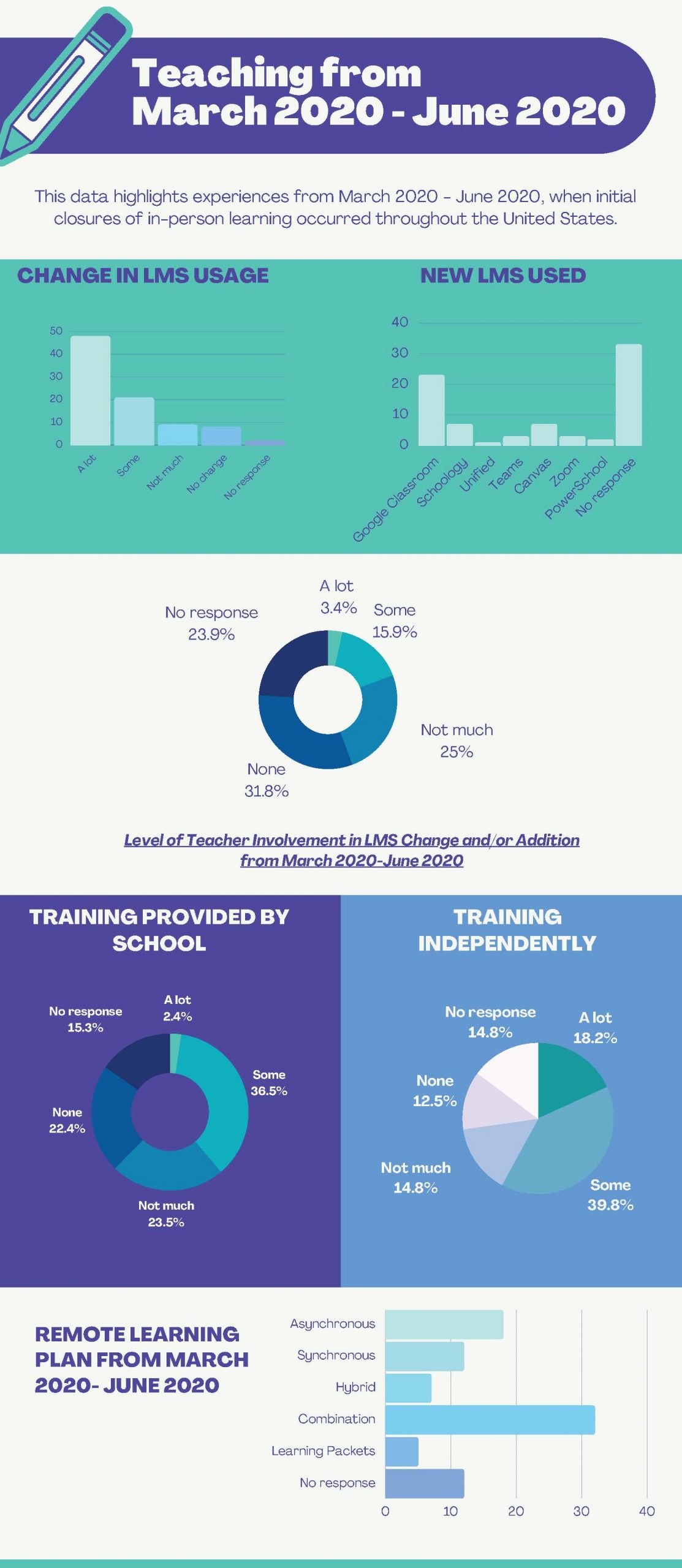

According to our survey, 21% of teachers had an asynchronous learning plan, 14% had a synchronous learning plan, 37% had a combination of the two, 6% used learning packets, and 14% did not respond to this question (see Appendix). It was interesting how a small percentage of teachers reported using learning packets during this time (see Appendix). While the data was not collected on why these districts chose to use learning packets rather than digital learning, perhaps this was related to lack of computer and Internet access.

One teacher described their school’s learning plan by saying, “[We had] class meetings once a week via Zoom. Teachers posted assignments in Google Classroom. Special teachers were required to make a video lesson each week for each different grade level and join a classroom Zoom each week” (see Appendix). Another teacher explained, “There was not a plan when we went into lockdown; every teacher chose whatever they were comfortable with” (see Appendix). Lastly, one of the respondents commented on their school’s asynchronous learning plan as “1 assignment per week” (see Appendix).

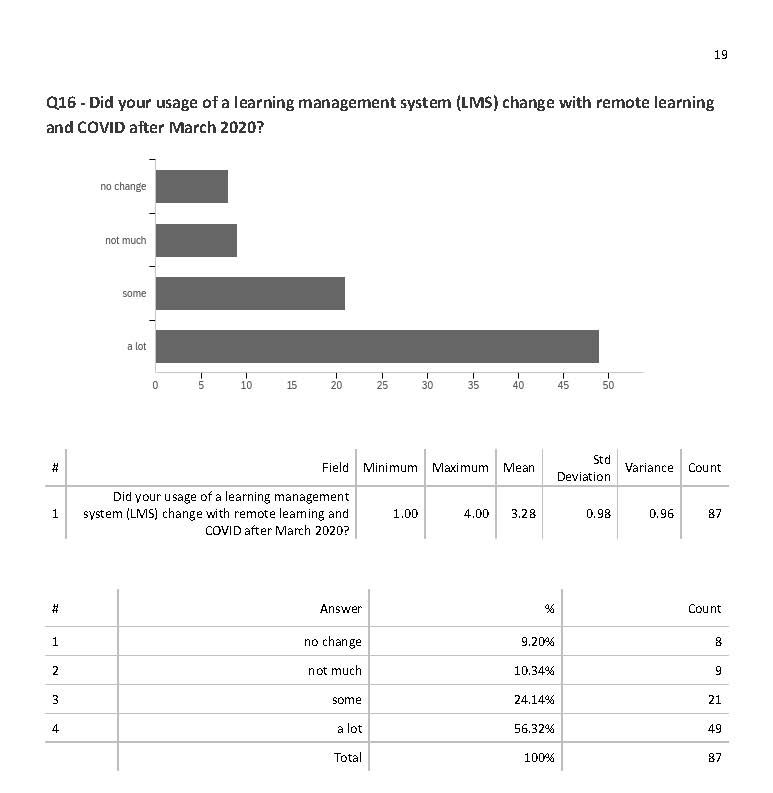

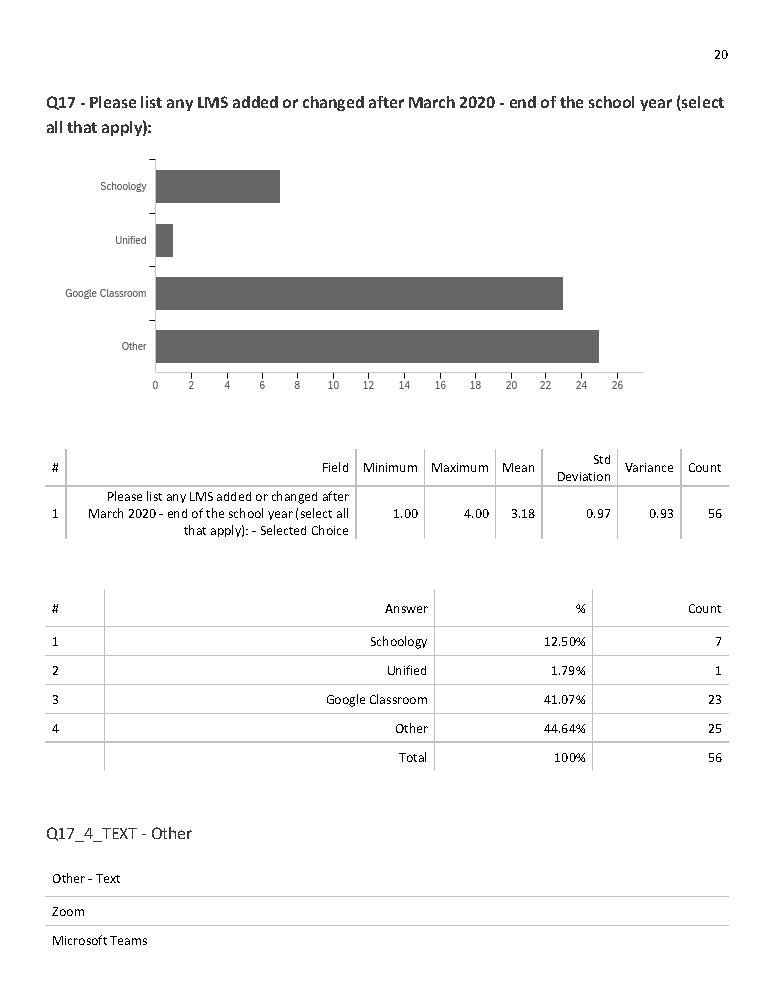

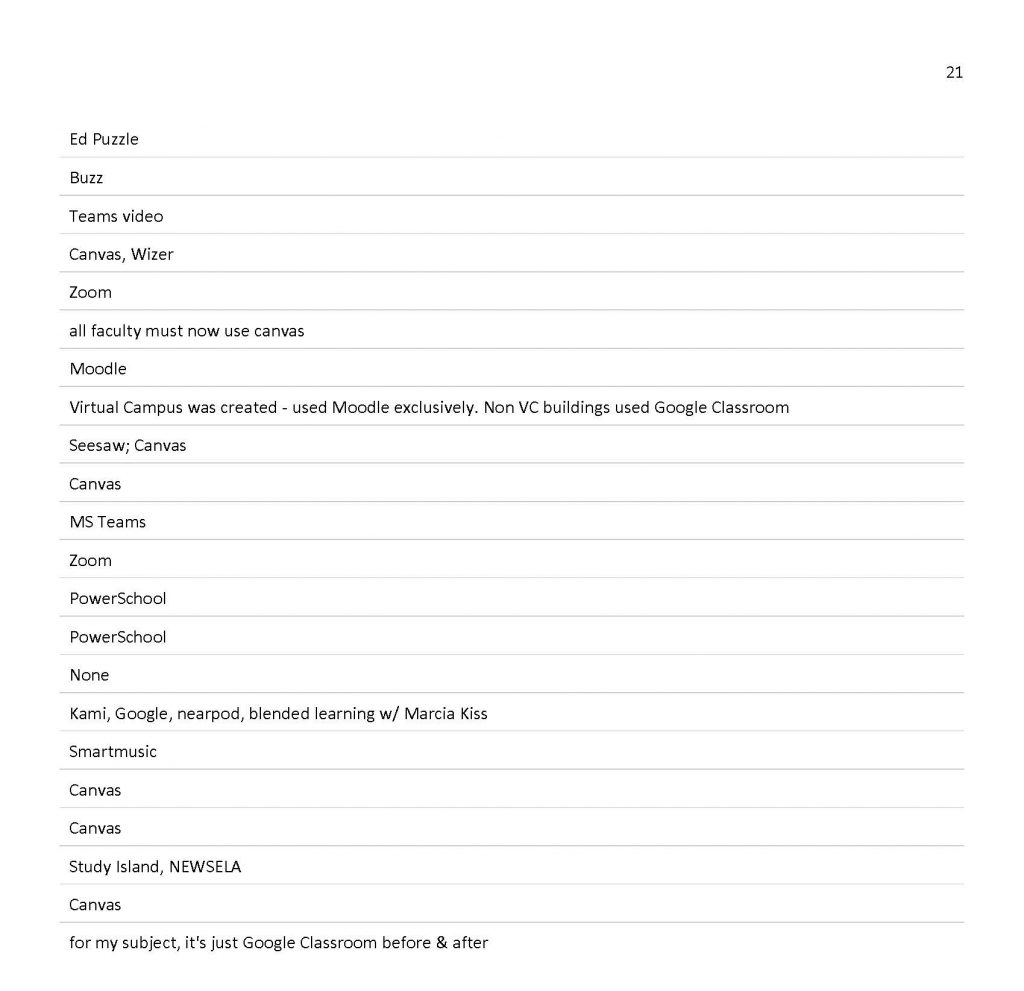

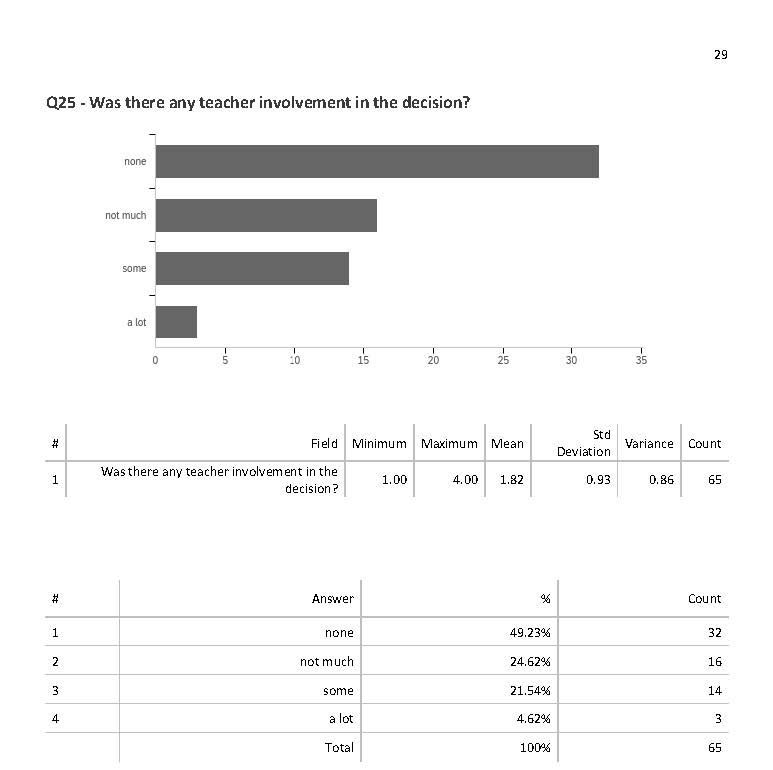

This shift to distance learning resulted in a large percentage of teachers greatly expanding their usage of learning management systems during this time (see Appendix). Herold (2022) describes how “Just two months after COVID-19 shut down the nation’s physical schools, 68 percent of survey respondents were telling the EdWeek Research Center that they were now using online learning management systems to collect and return student work.” In our survey, most teachers gravitated towards Google Classroom as their LSM during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (see Appendix). Herold (2022) writes that “One of the biggest shifts during those early months of all-remote learning…was that [Google] Classroom went from a supplementary tool to a central hub.” Other teachers turned to Schoology, PowerSchool, Blackboard, Unified, Harmony, Brightspace, Synergy, D2L, Maestro, Canvas, Seesaw, Zoom, Teams, Moodle, Kami, Nearpod, Study Island, NEWSELA, Wiser, and Virtual Campus (see Appendix). Ultimately, it should be noted that very few teachers were able to be involved in the decision-making related to which LSM were chosen during the March 2020 timeframe (see Appendix). Similarly, Polikoff (2022) noted that “teachers reported moderate to low levels of preparation and support to deliver remote curriculum early in the pandemic” (p. 6).

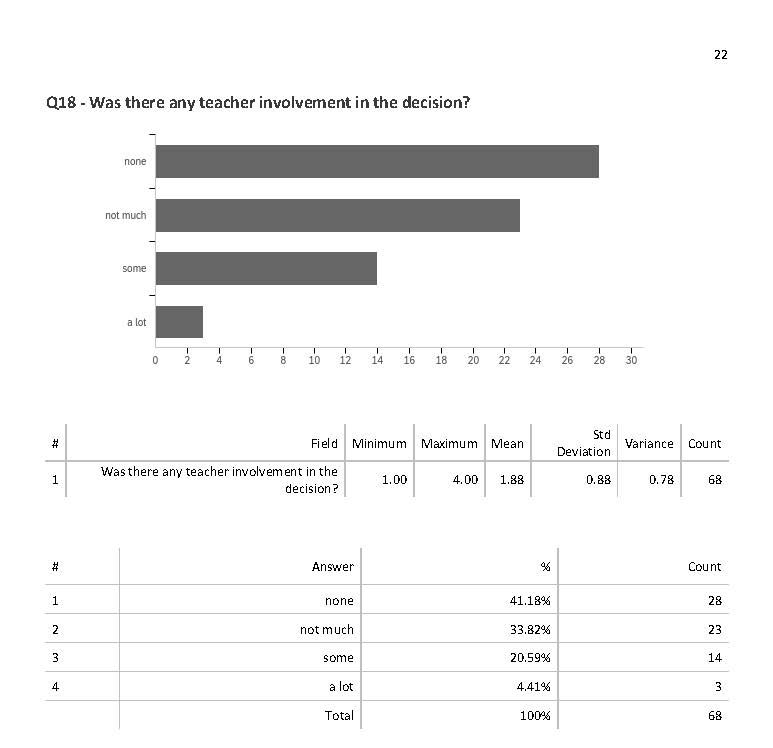

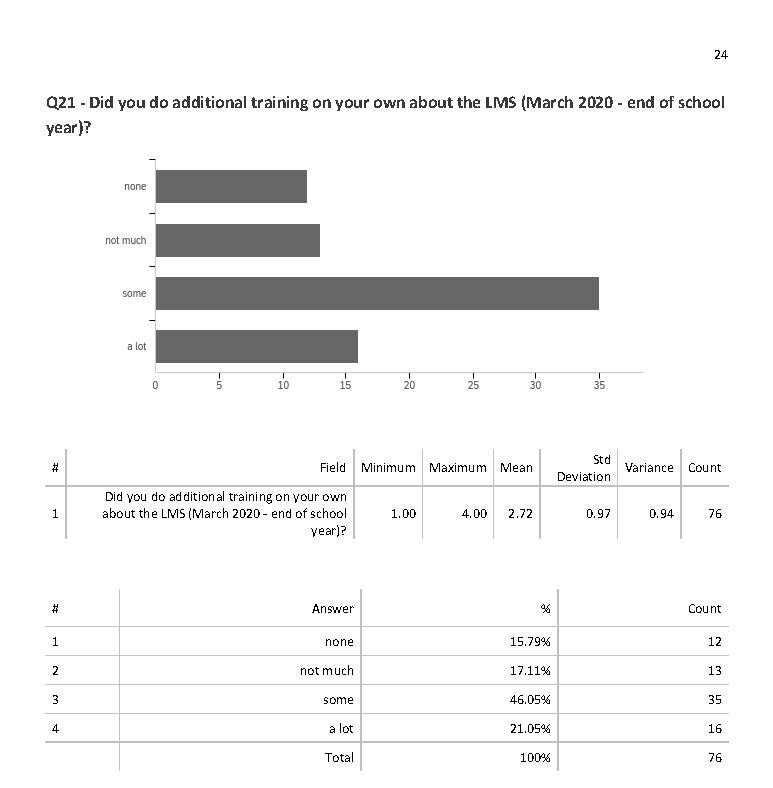

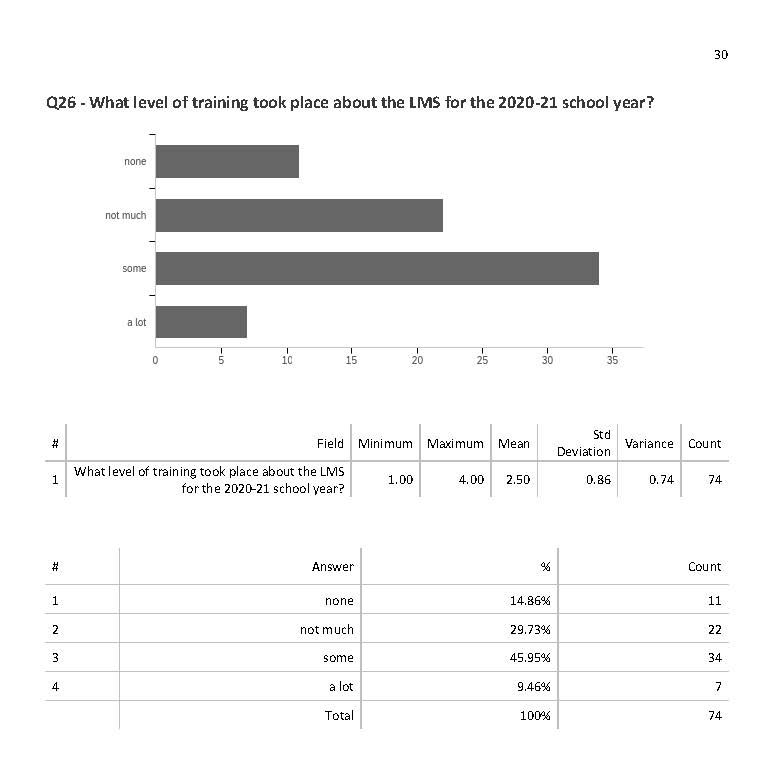

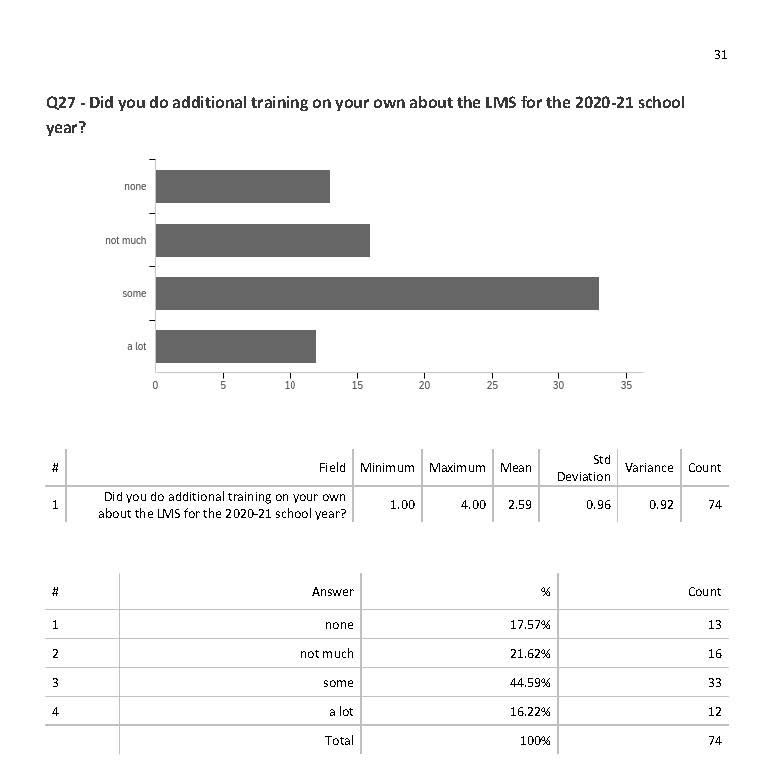

Among the great change in usage of LMS, in our survey, more than half of teachers reported that “none” to “not much” training took place to support teachers during the March 2020-June 2020 time while the remaining percentage experienced “some” training (see Appendix). As a result, half of these teachers sought out “some” additional training on their own about the LMS, while approximately 20% sought out “no” additional training, 20% “not much” additional training, and 20% “a lot” of additional training (see Appendix). Perhaps this lack of training can explain why teachers “…were primarily [using their LMS] to facilitate the submission and grading of assignments, followed by sharing learning materials, sharing videos and providing announcements and updates” within this timeframe (Francom et al., 2021, p. 594). Herold (2022) notes that “By the summer of 2020, three-fifths of principals and district leaders said they had provided teachers training on how to do such basic tasks.”

In addition to the increased reliance and usage of LMS, teachers used “technology-supported solutions and self-teaching” such as YouTube tutorials, searching for information online, trial-and-error, and contacting other teachers for help as strategies during this time (Francom et al., 2021, p. 594). In preparing educational activities for students, many teachers chose to review concepts that had already been taught rather than teach the remaining curriculum. In one survey, only 12% of teachers reported that “…they were covering all or nearly all of the curriculum they would have covered if school remained open…” (Polikoff, 2022, p. 6). Polikoff (2022) notes that “Fifty-three percent of teachers indicated they needed academic lesson plans to use with students while their school building was closed” (p. 6). Therefore, Francom et al. (2021) indicate that most teachers focused on providing learning activities and assignments using “…videos, journals, projects, research papers, and quizzes/tests to continue with the learning” (p. 592). During this March 2020-June 2020 timeframe, teachers reported an extreme decrease in instructional time (Polikoff, 2022, p. 6). Despite lack of core curriculum materials, “…teachers actually reported greater curricular needs in areas like social/emotional learning and hands-on learning opportunities (types of materials that may be less available or lower quality in online repositories)” (Polikoff, 2022, p. 6). Ultimately, Polikoff (2022) states that “… it was clear that students were far less able than pre-pandemic to have access to a quality curriculum” (p. 5).

Francom et al. (2021) describes multiple challenges that teachers faced during this unprecedented time of education. Teachers struggled to contact and communicate with students as well as “… get them participating and motivated, keep them engaged, and make them accountable for their learning” (Francom, et al., 2021, p. 595). Similar to the findings in the TeamLMS survey where teachers had very little training and support on their LMS in the transition to distance learning during March 2020, Francom et al. (2021) also notes that teachers struggled with “…setting up a distance learning course, finding and creating online resources, monitoring student progress and providing instructional support…” (p. 595). Furthermore, teachers faced challenges with student Internet and computer access and overall lack of parental involvement and support (Francom, et al., 2021, p. 596).

Students and teachers were not the only ones struggling with the educational experience during this onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Distance learning resulted in an increase for at-home instructional support (Polikoff, 2022, p. 7). Many parents grappled with how to best help their learners at home. However, Polikoff (2022) notes that “Despite the lack of confidence among parents that they could provide adequate instructional support, there was clearly high demand among parents for educational resources to support their children” (p. 8). This was evident via “one national study of parents’ web searches [that] indicated substantial increases in parents’ searches for both school-centered resources (e.g., Google Classroom, up 95%; Khan Academy, up 50%) and parent-centered resources (e.g., “online school”, up 50%; “online classes,” up 67%)” (Polikoff, 2022, p. 8).

With all of these challenges that administrators, teachers, students, and parents experienced, there was hope that the 2020-2021 academic year would bring a fresh start and a return to normalcy in schools. However, the COVID-19 pandemic would not be finished by the fall of 2020 and would continue to alter the traditional face of education.

K-12 Teacher Use of LMS and Technology During COVID-19 Phase II (2020 – 2021 School year)

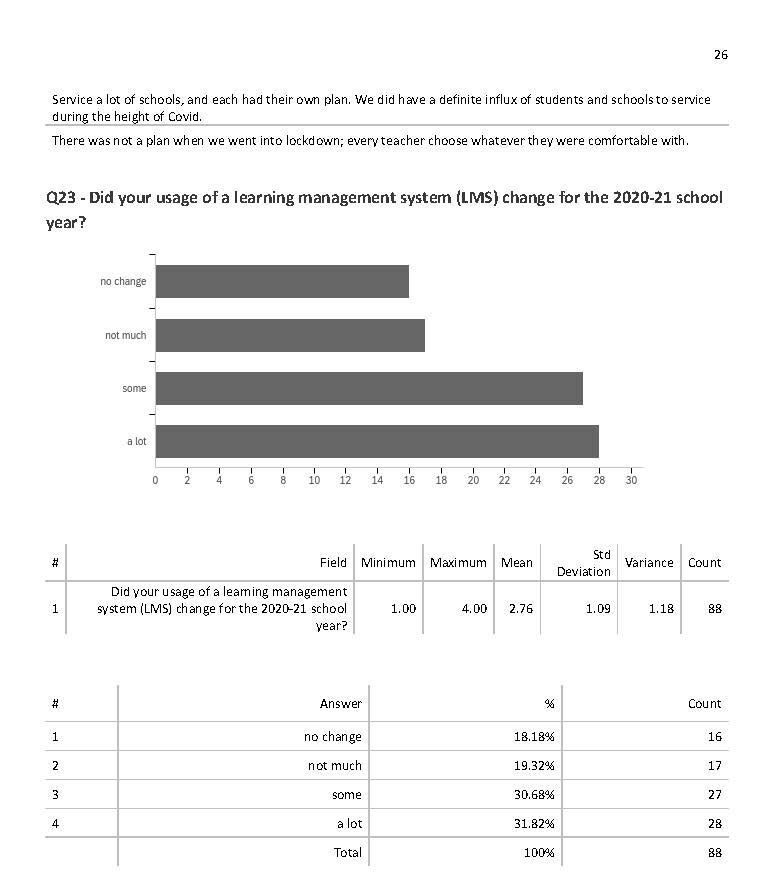

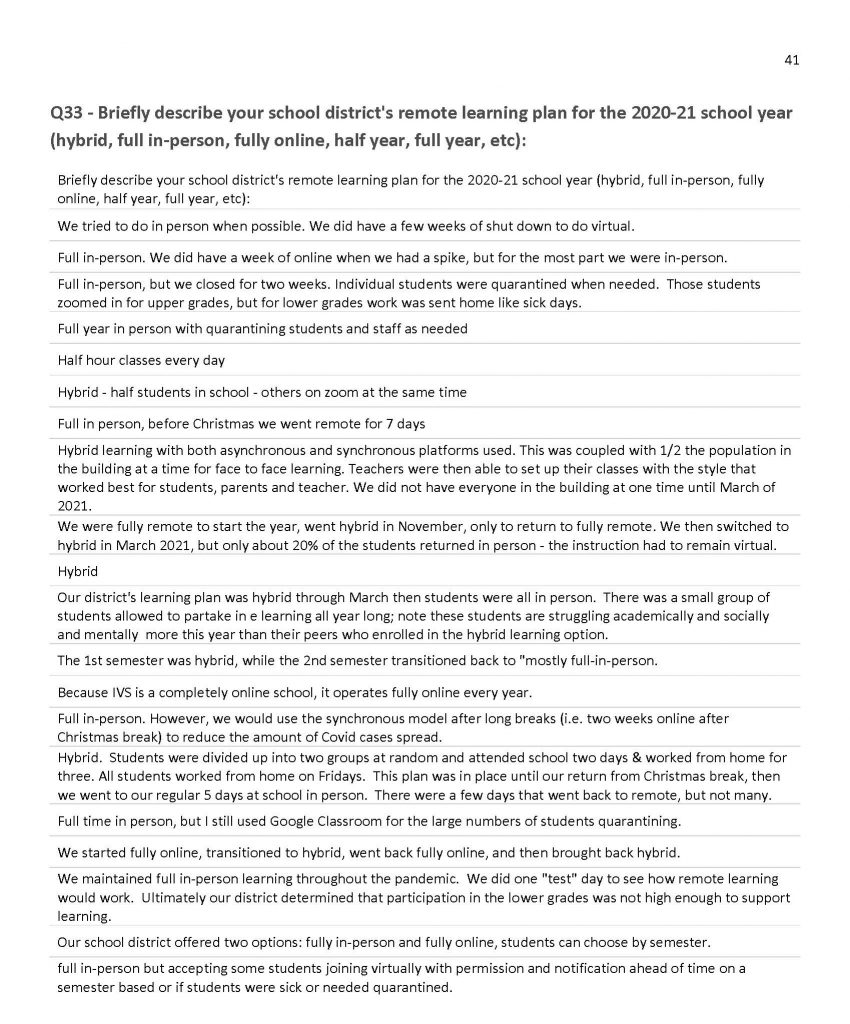

As many know, COVID-19 changed the way education is currently conducted. In the midst of this pandemic, there was definitely an unknown approach to how schools were going to reopen in phase two. Our survey looked at the second phase of COVID-19 during the 2020-2021 school year. As previously mentioned with COVID-19, the usage of LMS changed and was the main platform for education outreach for teachers and students. This transition can be seen with the data that was collected for our survey (see Appendix).

The “Teaching Method-Time Lapse” from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) gives a visual representation on the entire United States and how their school districts approached the 2020-2021 school year. When watching the time lapse, there is a majority of the school district unknown with their back-to-school approach for the 2020-2021 school year even in early August (MCH Strategic Data, 2022). With most schools going to school at some point in August, the time lapse shows just how much uncertainty there was with school districts as they were trying to navigate the unknown (MCH Strategic Data, 2022). As the time lapse progressed forward throughout the 2020-2021 school year, a majority of the schools had some type of hybrid approach to learning (MCH Strategic Data, 2022). This means there were students learning in person and some virtually. This was usually due to quarantines and exposure of kids and staff in the school system.

“Even in the 2020-2021 school year, just under a third of teachers (31%) in a national survey agreed that their curricula were easy to adapt for distance learning” (Polikoff, 2022. p. 6). When considering what teachers had to do from March 2020 to the start of the 2020-2021 school year, there was a lot of transition. The curriculum needed to be reinvented and redesigned for the new school year. As just mentioned, many school districts did not know what their 2020-2021 school year was going to look like until weeks or even days heading back to school either via in person or virtual (MCH Strategic Data, 2022). Even with an approach of hybrid learning, teachers were able to find ways to interact and connect with their students through the 2020-2021 school year through technology. According to CBInsights, virtual realities (VR) became a more utilized way of teaching (Education in a Post COVID World). Virtual realities are 3D environments that allow students to engage in learning from a specific location without needing to be onsite. This allowed students to participate in learning such as the Great Barrier Reef by participating in the online virtual realities (Education in the Post-COVID World: 6 Ways Tech Could Transform How We Teach and Learn, 2020).

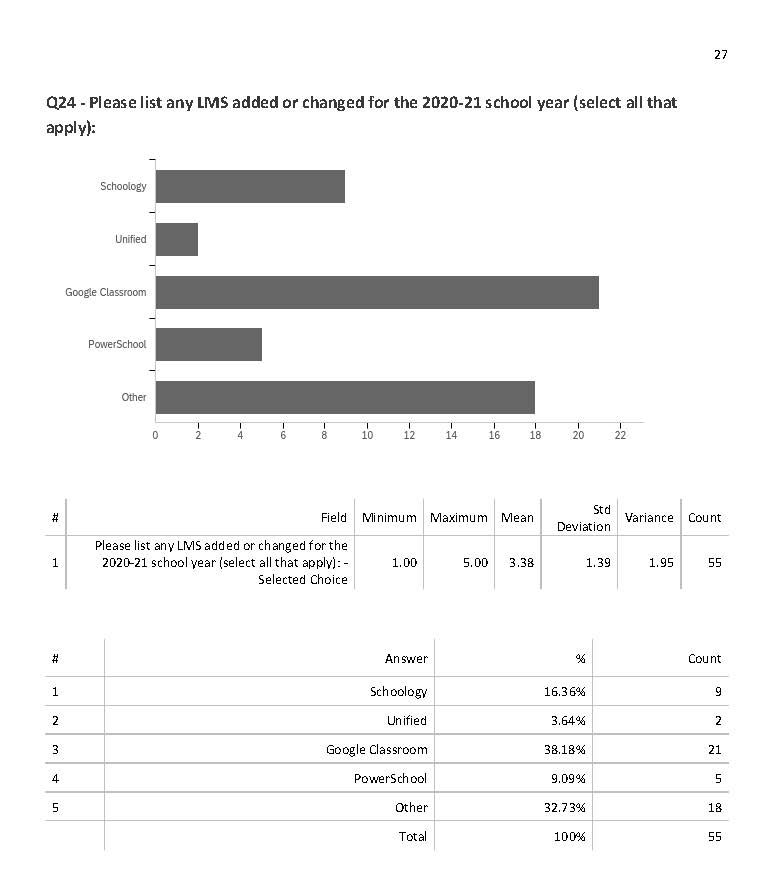

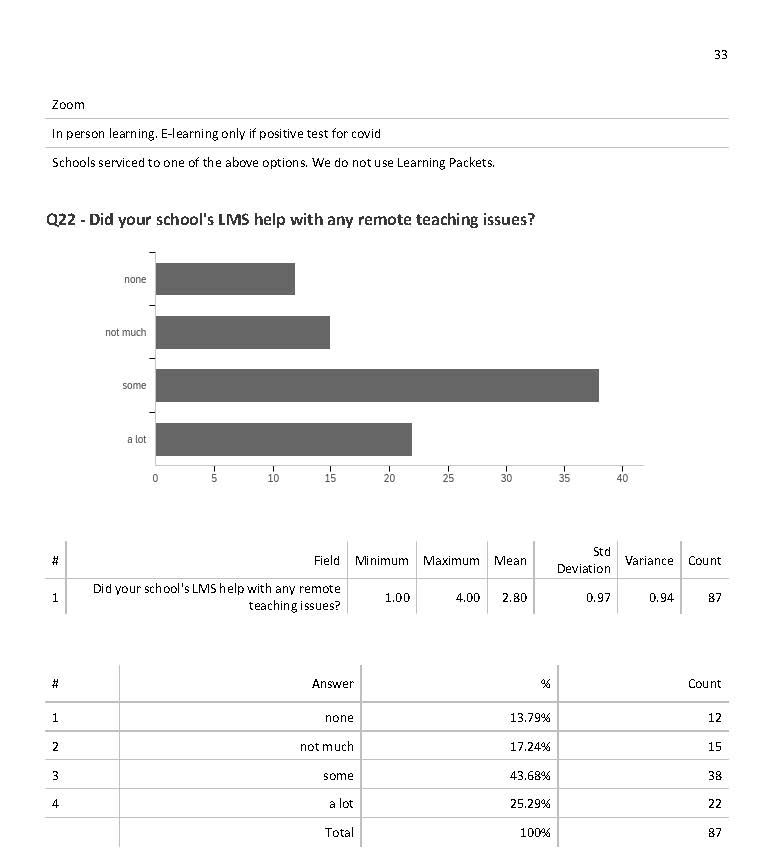

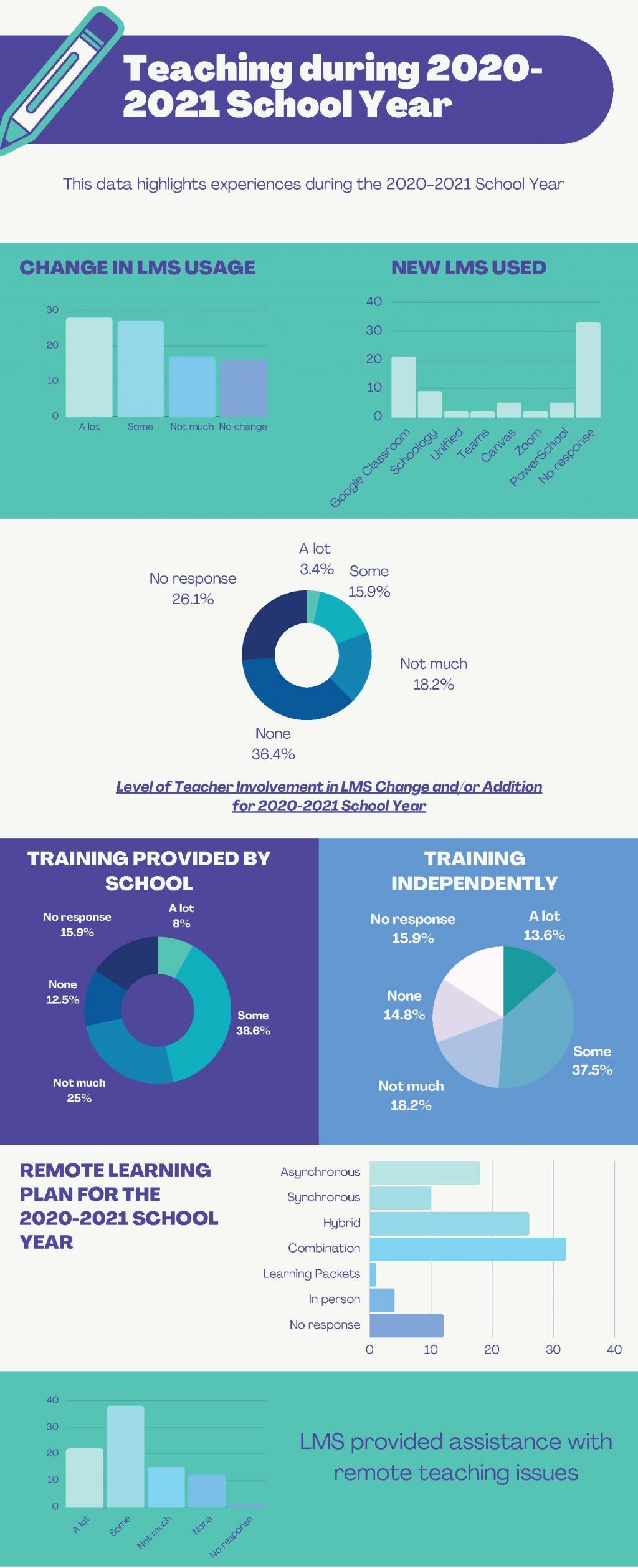

With the transition into the 2020-2021 school year, there was much uncertainty on how to approach education. With the transition, there was an adaptation of the HyFlex (Hybrid Flexible) or hybrid model of education. This included both virtual online learning and face-to-face instruction. In many cases, this approach has occurred simultaneously. Teaching instruction this way has brought about its own challenges as teachers had to be flexible and prepared for a flip in instruction at any given moment. According to our survey, the majority of the participants had indicated google classroom was the most used LMS (see Appendix). Once the pandemic occurred, the participants of the survey indicated their usage of their LMS increased (see Appendix). With this adaptation, it is clear to see teachers had to adjust their way of teaching with the usage of technology.

Herold (2022) noted that “By the start of the 2021-2022 school year, 48% of survey respondents told the EdWeek Research Center they started using Google Classroom during the pandemic and planned to continue on, the highest such figure among all the products asked about by name.” Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was reported in our survey that 44% indicated that their school LMS was Google Classroom, 23% with Schoology, 5% with PowerSchool, and 26% utilized some other LMS platforms (see Appendix). When addressing the comments in the survey, there was mention of LMS platforms such as Moodle, Harmony, Teams, and Canvas (see Appendix). There were also several mentions of a multitude of LMS platforms being used together, such as Google Classroom and PowerSchool (see Appendix). As progression was made into the 2020-2021 school year, there was 63% who reported their LMS platforms changed to some degree or larger with the new school year (see Appendix). With the transition to more of a hybrid model in 2020-2021, teachers reported there was additional training on LMS. When looking at the survey, 61% indicated they received some to a lot of additional training on LMS for the 2020-2021 school year (see Appendix).

Lessons Learned and Reflections

This chapter analyzed how teachers evolved their use of learning management systems to adapt to remote learning due to COVID-19. This shift to remote learning with little warning highlighted the adaptability and versatility of teachers across the nation. With various levels of experience, teachers utilized learning management systems to the best of their abilities to continue to educate their students. However, questions still remain of what lessons were learned and what teaching will look like in the future (Li & Lalani, 2020).

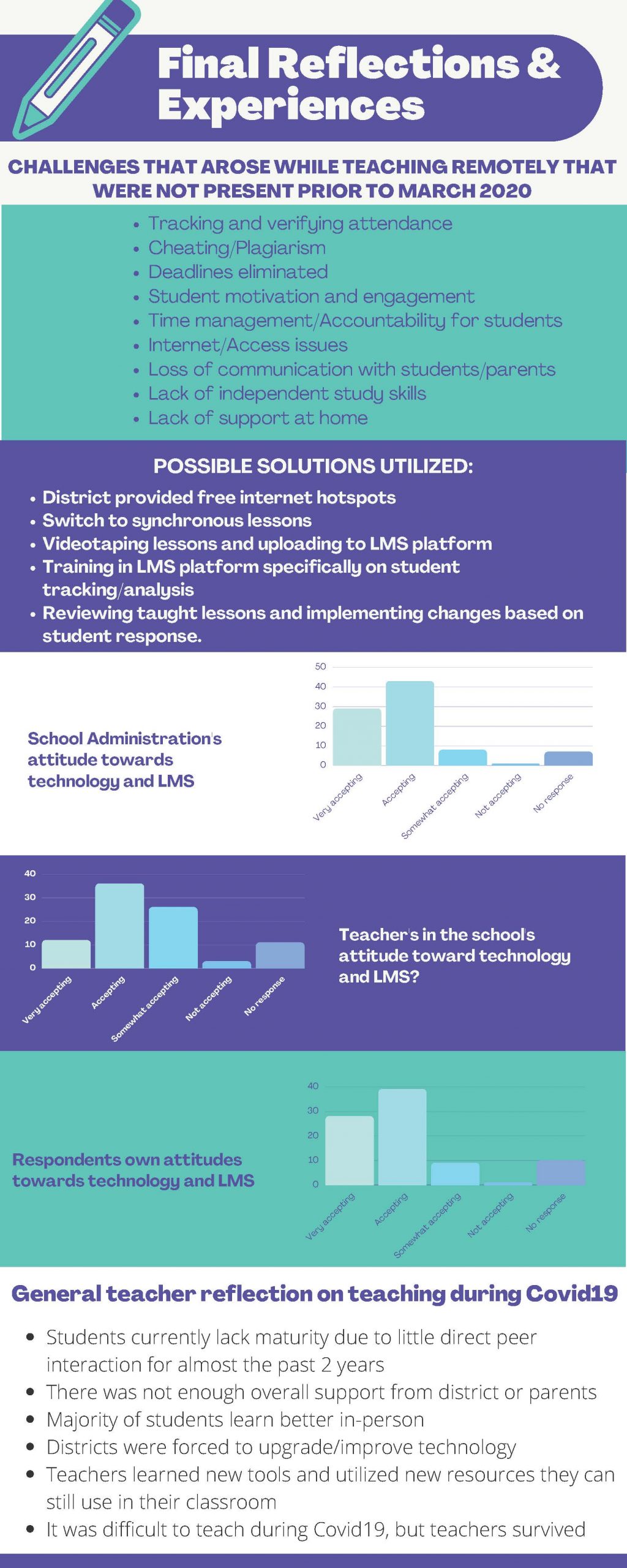

With the quick transition to remote learning, challenges were numerous, with some including administrative (tracking attendance), student engagement, cheating/plagiarism, and overall accountability for students who were now responsible for monitoring their own time management and communication (see Appendix; Olson, 2021). Additionally, there were numerous challenges that students and teachers couldn’t control, such as reliable internet access (see Appendix). These challenges highlighted weaknesses in remote learning, but also showed school districts and communities where they could improve.

Some solutions that were identified through the Team LMS survey to these challenges included:

-

-

-

- School districts provided free hotspots to students

- School districts moved away from asynchronous lessons to synchronous through video conferencing platforms

- Teachers adaped lessons based on student feedback and self-reflection

- Teachers recorded and uploaded their lessons to their LMS platform for students to learn on their own time/availability if they couldn’t make it to the synchronous class

- School districts provided extensive professional development for LMS platforms to learn how to track/analyze student progress

-

-

In contrast to the challenges, the quick transition to remote learning resulted in a fast rise of numerous online learning resources for students, teachers, and even parents (Herold, 2022). With numerous platforms offering free or discounted resources, teachers were able to try different LMS platforms along with supplemental platforms for specific needs, such as literacy or math (Li & Lalani, 2020). The transition also encouraged a focus on education tools, such as Google improving their videoconferencing and developing an “offline mode so that students struggling to find a reliable WIFI signal on their mobile device could still access their assignments” (Herold, 2022). The Economist discusses COVID-19 and the effect of technology on education in this video: Covid-19: how tech will transform your kids’ education (The Economist, 2021). Also, this video by NBC4i asks three Ohio teachers to look back on the past year and their experiences with the pandemic: One year later: Teachers reflect on remote learning, return to class (NBCi4, 2021).

After experiencing the rapid switch to remote learning, teachers are now able to reflect on the experience as whole. From the TeamLMS survey, many teachers expressed concern about student maturity since many students went a full two years without in-person interactions with students their own age. Additionally, teachers observed that those students who struggled with self motivation and time management prior to Covid19 continued to struggle in a virtual setting and many students did not progress or learn the required content – rather they just did the bare minimum to pass. Finally, many teachers mentioned that in-person learning was still preferred as students benefited from the structure of a classroom where they could receive immediate feedback and assistance (and “not hide behind a screen”). However, this experience also had positive points as it forced many districts to update their technology and LMS platforms that had previously been postponed. Additionally, districts are utilizing remote learning for students who are absent over long periods of time and for calamity days that occur throughout the school year.

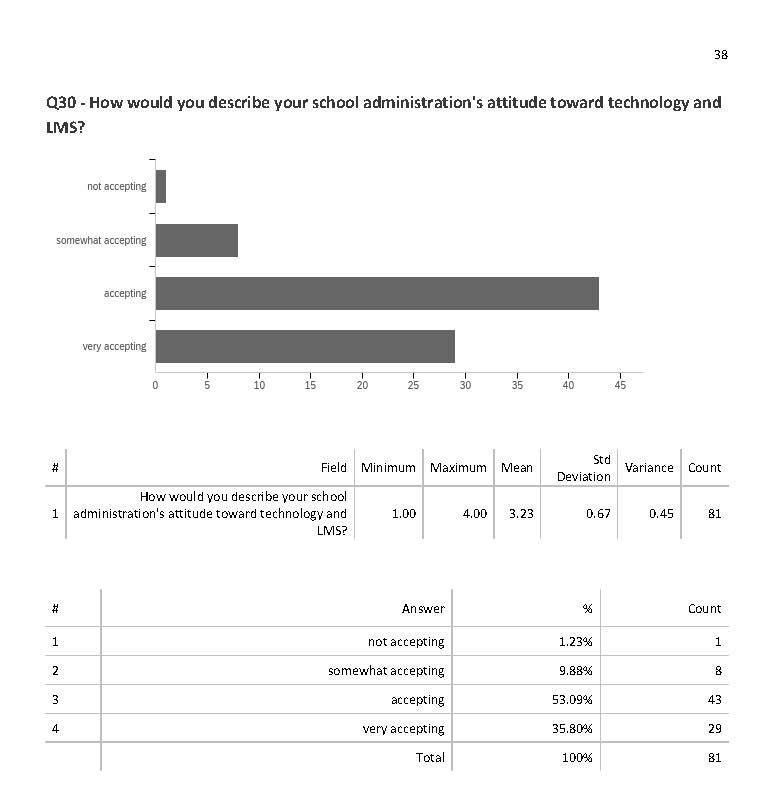

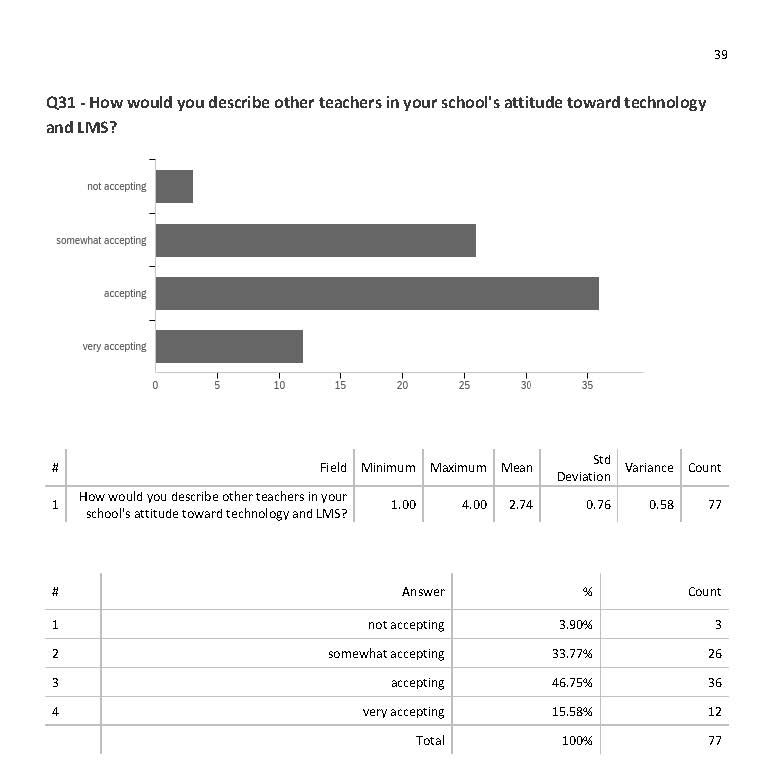

The challenges and benefits of remote learning were felt by all involved in education. However, both teachers and administrators rose to this unprecedented experience with accepting attitudes to take on the difficult task of learning new technologies and LMS platforms to best teach their students (see Appendix). In doing so, teachers and administrators worked to provide the best educational experience for students with the resources and knowledge available to them. Future researchers and educators will continue to reflect upon these experiences to continuously learn and improve upon the challenges that all faced and ultimately help to create a better learning environment for all students across the globe.

References

Aditya, D. S. (2011). Embarking Digital Learning Due to COVID-19: Are Teachers Ready? Journal of Technology and Science Education, 11(1), 104-116. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1303147

Alserhan, S., & Yahaya, N. (2021). Teachers’ perspective on personal learning environments via learning management systems platform. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (IJET), 16(24), 57–73. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v16i24.27433

Dindar, M., Suorsa, A., Hermes, J., Karppinen, P., & Näykki, P. (2021). Comparing technology acceptance of K‐12 teachers with and without prior experience of learning management systems: A Covid‐19 pandemic study. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(6), 1553–1565. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/10.1111/jcal.12552

EdSurge. (2017). Cracking the Code: How Practitioners Conceptualize and Implement Personalized Learning. https://d3btwko586hcvj.cloudfront.net/static_assets/pl/EdSurge_PL_Report_103117A.pdf

Education: From disruption to recovery. UNESCO. (2022, February 28). Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse#durationschoolclosures

Education Week. (2020, June 4). Teaching in the Time of Coronavirus: Meet the Teachers. Youtube. other. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://youtu.be/T8tQrh6IOVo.

Education Week. (2020, July 8). The coronavirus spring: The historic closing of U.S. Schools (a timeline). Education Week. Retrieved April 10, 2022, from https://www.edweek.org/leadership/the-coronavirus-spring-the-historic-closing-of-u-s-schools-a-timeline/2020/07

Educational Technology Infographics. (2013). (rep.). The History of Learning Management Systems Infographic. Retrieved April 12, 2022, from https://elearninginfographics.com/category/educational-technology-infographics/.

Fehely, D. (2020, March 30). Teachers, Students Embrace Technological Challenges As Coronavirus Sheltering Shifts Learning Online. YouTube. other, KPIX CBS SF Bay Area. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://youtu.be/Uj63uMyQq-Q.

Francom, G.M., Lee, S.J. & Pinkney, H. Technologies, Challenges and Needs of K-12 Teachers in the Transition to Distance Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. TechTrends 65, 589–601 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00625-5

Herold, B. (2022, April 12). How tech-driven teaching strategies have changed during the pandemic. Education Week. Retrieved April 13, 2022, from https://www.edweek.org/technology/how-tech-driven-teaching-strategies-have-changed-during-the-pandemic/2022/04

Hill, E. E., Jr. (2009). Pioneering the use of learning management systems in K-12 education. Distance Learning, 6(2), 47.

Lewis, C. G. and L. (2021, November 16). Use of educational technology for instruction in public schools: 2019–20. National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, a part of the U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved April 13, 2022, from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2021017

Li, C., & Lalani, F. (2020, April 29). The COVID-19 pandemic has changed education forever. this is how. World Economic Forum. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-education-global-covid19-online-digital-learning/

MCH Strategic Data. (n.d.). Covid-19 impact: School district operational status. updates for Spring 2022. COVID-19 IMPACT: School District Operational Status. Retrieved April 15, 2022, from https://www.mchdata.com/covid19/schoolclosings

NBCi4. (2021, March 19). One year later: Teachers reflect on remote learning, return to class [Video]. NBCi4. https://www.nbc4i.com/news/local-news/one-year-later-teachers-reflect-on-remote-learning-return-to-class/

Olson, L. (2020). How Can Learning Management Systems Be Used Effectively to Improve Student Engagement? Center on Reinventing Public Education, 2021-Jan. ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED610602

Pelletiere, N. (2020, October 8). Teacher’s tearful selfie video reveals challenges of online teaching amid COVID-19. other, GMA Digital. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.goodmorningamerica.com/living/story/teachers-tearful-selfie-video-reveals-struggles-online-teaching-73360489.

Polikoff, M. S. (2022). Lessons for Improving Curriculum from the COVID-19 Pandemic. CRPE Reinventing Public Education. https://crpe.org/wp-content/uploads/v2-Polikoff-working-paper.pdf

Schoology. (2020). (rep.). The State of Digital Learning 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2022, from https://info.schoology.com/rs/601-CPX-764/images/State_of_Digital_Learning_in_K-12.pdf.

Siu, Antoinett. (2016). A Timeline of Google Classroom’s March to Replace Learning Management Systems. EdSurge. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2016-09-27-a-timeline-of-google-classroom-s-march-to-replace-learning-management-systems

Sweeney, T. (2019). Google Classroom vs Schoology: an LMS Comparison. YouTube. Retrieved April 12, 2022, from https://youtu.be/rYQcyX_L8N4 .

The Economist. (2021, September 13). Covid-19: how tech will transform your kids’ education. Youtube. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://youtu.be/9vD0BYBh5c4.

Zara, C. (2022, January 10). Schools closing due to Covid: Track district updates as Omicron spreads. Fast Company. Retrieved April 15, 2022, from https://www.fastcompany.com/90711741/schools-closing-due-to-covid-track-district-updates-as-omicron-spreads

Appendix

Team LMS Survey

This appendix includes all of the raw data from our survey of 93 teachers. Data used in the chapter reflects the 88 respondents completing 75% or more of the survey.