7 Chapter 3 – Comparative study on technology inequity between China and US during COVID

Comparative study on technology inequity between China and US during COVID

Seymour Papert some three decades ago wrote, ” we are at a point in the history of education when radical change is possible, and the possibility for that change is directly tied to the impact of the computer.” (Papert, 1980, p.36). Technology in education these days has become part of a regular procedure rather than for special reasons. According to Bruder (1989), ” for years, the microcomputer was cited as the vehicle for overcoming a wide array of inequities. Today, interactive televisions, electronic mail, and expanded telecommunication networks are promoted as avenues to improve resources for underserved students.

Biased or unfair policies, programs, practices, and situations contributed to a lack of inequity in educational performance, results, and outcomes (Education reform,2016). This chapter focuses on technology inequity in K-12 education. We will explore technology inequity in K-12 education during COVID-19 by comparing two countries, China, and the US. This is important because China and USA have been one of the hardest-hit countries by COVID-19 where school closures compelled education systems to devise and employ different modes of remote learning and various other types of online tools.We will be answering the questions:

What are the similarities and differences between China and US?

How did Covid-19 increase the technology inequity gap?

What can be done to decrease the gap and increase access?

How does COVID-19 create Inequity in K-12 Education?

What is Technology Inequity?

Over the past few years, technology has become a major tool used in just about every career field and has provided educators with a valuable resource to support teaching and learning (MacCallum, Jeffrey, &Kinshuk,2014). Educational technology (Edtech) represents efforts to design, develop, and use technology to achieve a never-ending array of desirable educational outcomes, including improving learning, increasing retention rates, enhancing teaching effectiveness, reducing costs, and increasing access. Throughout its history, Edtech proponents have assumed positive impacts, promoting optimistic rhetoric despite little empirical evidence of results and ample documentation of failures. Technologically savvy students often have a better chance of getting a job and excelling in their careers (Savage & Brown, 2015).

When used effectively, technology can greatly contribute to creating equity in schools. It removes barriers to learning materials, supports students where they are across varied learning contexts and needs, and gives educators more insight into the learning environments they’re creating (Anderson,2019). However, the task of integrating technology into classroom instruction in a meaningful and state-of-the-art way remains challenging (Pittman & Gaines, 2015). Although classrooms may have access to many technology devices, several external and internal factors affect the proper implementation of technology in some of these classrooms due to biased and unfair policies resulting in a lack of equality in educational performance and outcomes (the desire results in teachers and stakeholders want students to achieve).

These biased or unfair practices could be implicit or explicit. Implicit bias could be an unconscious racial or socioeconomic bias toward students. For instance, Instructors can hold assumptions about students’ learning behaviors and their capability for academic success which are tied to students’ identities and/or backgrounds, and these assumptions can impede student growth (Staats, et.al, 2017). An example could also be how learners engage with a technology product based on how the product was designed. Some factors may also include, low teacher self-efficacy, poor infrastructure, teacher perceptions, effective professional development, lack of sufficient technology, and inadequate technology. Whiles equity is complex and requires addressing multiple dynamics such as socioeconomic, cultural, familial, staffing, linguistic, instructional, and assessment. In this chapter, we will focus on the comparison of access and its impact during the pandemic.

Image credit: https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3076954/hong-kong-must-address-deeper-digital-inequalities-exposed

Illustration: Craig Stephens

Technology inequity in China during Covid-19

Technology inequity in the US during Covid-19

With the unprecedented worldwide outbreak of COVID-19, most k-12 schools in the U.S. abruptly transitioned from traditional classrooms to emergency remote learning (ERL) classes in the middle of the 2020 spring semester. This was intended to reduce the risk of contracting the deadly virus within academic communities, making online learning the only choice for students to continue their studies for the remainder of the academic year. The switch to ERL not only changed the learning setting from a face-to-face context to a virtual remote context, but it also changed how students engage in the classroom, as students were abruptly required to be in online learning settings with little or no proper preparation or technical support. This quick and somewhat chaotic transition has been a substantial deviation from the norm, especially considering that a regular shift to online learning requires multidimensional preparations and adjustments (Redmond et al., 2018) and also access to different types of technologies such as digital devices, software, internet, etc.

Journell (2007) believes that technology inequity has remained its presence throughout history. During the COVID-19 pandemic, technology inequity increased dramatically (Beaunoyer, 2020). Researchers have shown different reasons why COVID-19 had a big and negative influence on technology inequity.

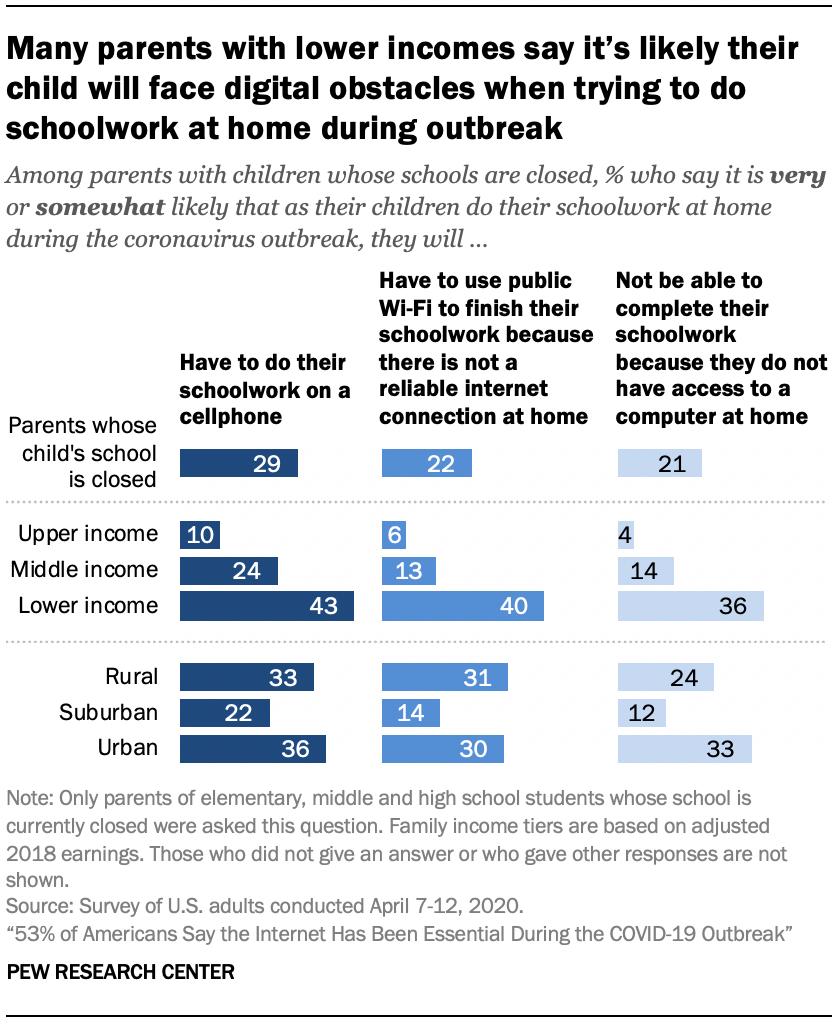

Low-income households with many children couldn’t afford multiple digital devices for their children to attend classes online (Beaunoyer et al, 2020a, Vogels et al., 2021). They had to share limited digital devices and sometimes their class schedules conflicted therefore they couldn’t attend class on time and missed class. In addition, many low-income parents asked their children to use public Wi-Fi to finish their homework during COVID-19 due to non-reliable internet connections at home (Vogels et al., 2021). However, it was comparably difficult for them to find a public Wi-Fi during COVID-19 than in the past.

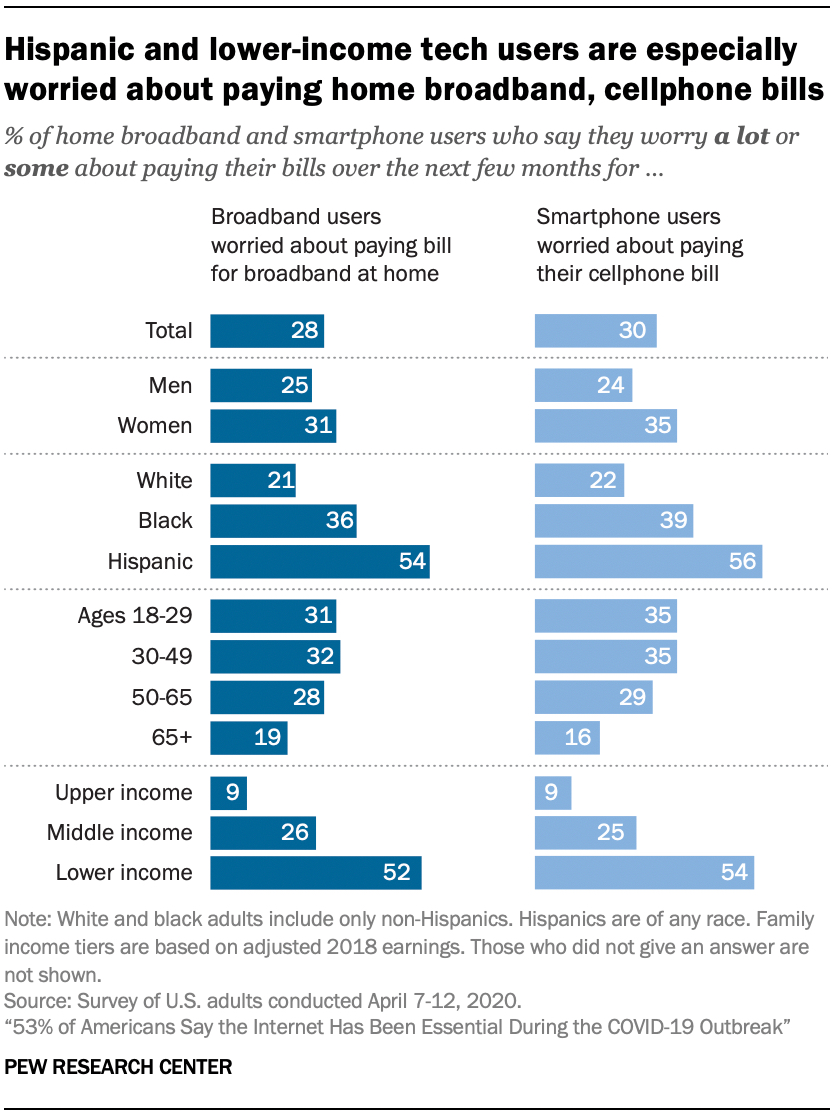

In terms of the accessibility of digital devices within different ethnic groups, researchers have found that digital devices were available to white people more than to other races during this pandemic (Collis and Vegas, 2020). According to Vogels et al. (2021), low-income households were concerned more about their tech-related bills, such as internet bills, cellphone bills, etc. More specifically, Hispanic households reported the most concerns among all ethnic groups.

What are the similarities and differences between China and US?

- Political System: In China, there is only one party “the Communist Party of China”. All the provinces must follow the central committee and conduct the same policy. While in US, there are Democratic Party and Republican Party. They have different policies in dealing with the pandemic. In Blue states, students are required to wear masks and take online classes. As the public service is not available during Covid, students who don’t have access to digital devices cannot participate in class. Whereas in red states, students can take in-person classes. They are less affected with digital access problems.

- Government Control: Chinese government is a centralized government. They published the “Disrupted classes, undisrupted learning” policy. Though the Chinese Ministry of Education (MOE) provide autonomy to the local government to arrange school activities, it is still the governments to take the responsibility. On contrast, US federal government only have a limited control. Each state has their own policies to deal with the pandemic.

- Social Background: China and US have different social issues.

- In China there is a unique phenomena called “left-behind children“. Left-behind children refer to children who are left behind in their hometowns or boarding with relatives because one or both parents are working outside the home. It is a serious social phenomenon in China. In the case of left-behind families, the parents need to go out to the city to work to make ends meet, but are unable to take their children because they cannot afford the high cost of living in the city. Lack of enough parental support, these kids need more concern to assist their learning during pandemic.

- Racial issue is a prominent concern in US. It is comprehensive, systemic and persistent. The minority group is facing with more inequity during pandemic. Black and Hispanic families with school-age children are 1.3 to 1.4 times more likely than white families to have limited access to computers and the Internet, and more than two-fifths of low-income families have limited access to devices. Racial minority group deserve more concern in the US.

- Value: Chinese parents and US parents also hold different value toward students academic performance. Most Chinese parents have high expectation on their children’s academic performance. They value the effort and diligence that students put into the academic tasks. While American parents value children’s overall wellbeing and development. Academic only takes a small part. Therefore, Chinese parents are more actively cooperate with school to support students learning.

Image credit: https://onlinedegrees.sandiego.edu/what-is-educational-technology-definition-examples-impact/

Even though there is some progress in the technological presence, teacher education is still a long way to go. The difference between online and offline is much more than the difference brought by an internet cable and a screen, but the essence of education, changing the Prussian education method that has never changed in 100 years of human history. With the dramatic development of technology, students should be provided with more personalized learning experience. The Summit school uses screens and technology to tailor learning to student’s needs, uses the best resources in the world to find master teachers in various fields, while offline teachers become the role of supporting students and answering questions and solving problems. It may shed some light on what future education looks like.

How did Covid-19 increase the technology inequity gap?

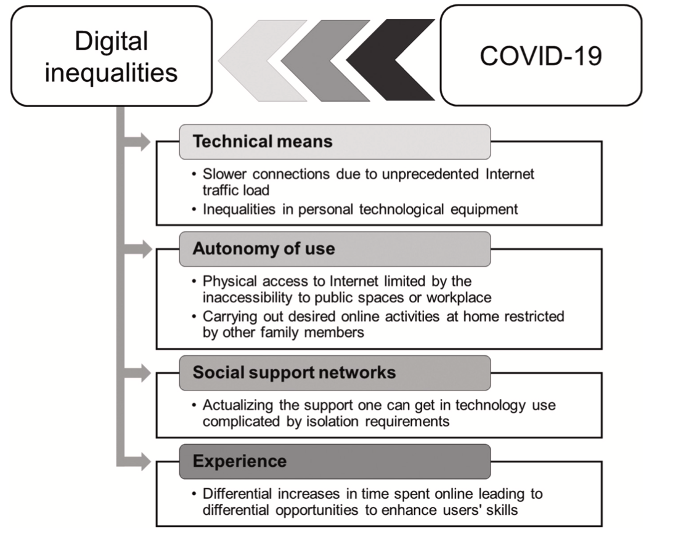

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, technology wasn’t necessarily a priority because, in daily life, people could function normally with little or no help from technology because of many reasons. (Beaunoyer et al., 2020a). However, the COVID-19 had changed the “status quo” and technology inequity became a serious issue, especially among certain groups. Salha et al. (2021) point out that technology inequity had been widened by COVID-19. Beaunoyer et al. (2020a) proposed a framework for how COVID-19 had impacted technology inequality and then how technology inequality has in return worsened the COVID-19 pandemic. In this framework, Beaunoyer et al. (2020a) summarized four factors that were deepened by COVID-19 and they are: technical means, autonomy of use, social support networks, and experience

- Technical means

The differences between low-income households and economically favored households widen the pre-existing equipment-based technology inequity due to limited access to technology equipment or upgrades to better technology equipment (Beaunoyer et al., 2020a). Fast internet was also an important factor during this pandemic. The faster and more stable the internet was, the faster one could get their online resource. However, that means more expensive internet bills. In addition, households with many children needed to share their internet together which could result in slower and unstable internet connections (Bergman & Iyengar, 2020).

- Autonomy of use

As many public services shut down during the pandemic, people who previously went to get a public internet connection couldn’t continue to do so. This made it extremely difficult for people who rely on public service to go online and study (Beaunoyer et al., 2020a). According to Fernandes (2020), COIVD-19 also brought a wave of unemployment which caused many people couldn’t access home internet connections. This in return limited people searching for jobs because they don’t have the equipment and internet to look for jobs online.

- Social support networks

For people who lack digital literacy, it was difficult for them to find support, especially during COVID. During this pandemic, many needed to learn how to use new technologies, or upgrade their current technologies. However, getting support from professionals was extremely difficult for those who didn’t have supportive social networks. Those who had lower digital literacy also faced obstacles when they were referring to help (Beaunoyer et al., 2020a).

- Experience

Previous experience in using technology also was an important factor during the COVID-19 pandemic. The more experience you had in the past of using the internet and digital devices, the better you could adapt yourself in this transition to online learning. People who weren’t in a technology-heavy environment might adapt to the new normal as fast as people who were using technology all the time in the past (Beaunoyer et al., 2020a).

What can be done to decrease the gap and increase access?

Technology in education is supposed to create opportunities for all, not just a few and specific groups of people. The National Center for Education Statistics conducted a survey that found only 61 percent of school-aged children had internet access at home, and yet a majority of students reported requiring the internet to complete assignments. Educational Inequity has been an issue in education for a very long time. The United States for instance faces technological segregation based on access, digital literacy, and cultural limitations. These social problems extend into public education, where one can see the beginning of a digital divide as far back as 1905 with the advent of school museums that housed forms of educational technology (Reiser, 2001). When covid -19 took the world by storm, schools had no option but to devise strategies for remote learning amid a lack of equipment, teachers, money, and structures. This exposed further the technology inequity that has existed for years by highlighting the inefficiencies in the current educational system.

According to Global Citizen, there exists a digital divide worldwide, and 40% of rural African American citizens don’t have broadband access at home compared to 23% of white Americans in the same area. The only way to bridge this inequity gap to attain the desired success is through Equity. This section looks into some measures to adopt to remove these disparities.

- Develop a Systematic Technology Plan: To build, implement, plan and provide equitable access to technology for students, schools should have a plan. Schools should be encouraged to develop a technology plan which will outline all the learning styles and characteristics of students, allowing leaders to work towards that goal.

- Liaise schools with local libraries: One simpler and considerably cheaper solution to take advantage of is involving the cooperation of school districts and neighboring communities. Schools could partner with local libraries to facilitate student computer access or even act as technology centers themselves after school hours (Brown et al, 2001). Servon & Nelson (2001) advocate the use of community technology centers that provide a place for those lacking computer access to use the Internet for information and recreational purposes. Currently, two-thirds of all technology centers are located in urban areas, most of them providing programs that improve digital literacy as well as delivering content, such as General Educational Development (GED) programs.

- Implement and Invest in Digital Tools that are Easily Accessible Offline to Promote Inclusiveness: According to The Tech Edvocate, 40% of students from low-income households were able to access remote learning once a week or less. When tools are easily accessible offline, these students who are at a disadvantage due to lack of internet connectivity will be able to download, read, and do other things even though there is no internet.

-

Ensuring Access for Digital Learning: When traditional teaching and learning went remote during the pandemic, digital learning became the talk of the day. To ensure digital learning occurs at home, schools and communities must ensure that every student has access to devices and reliable internet. There are many ways to do so, but the district and school leaders should also do what they can to advocate for sustainable digital access for all families. This can be accomplished through:

- Supporting families to identify free or low-cost internet service.

- Partnering with local service providers to increase access for families in the providers’ communities.

- Providing digital learning devices and tools to all families and students who do not have access.

Covid-19 exacerbated an already existing disparity between availability and access to technology. China and the US are two very different countries, with different governments and different resources for dealing with Covid. They also had different availability to educational technology before Covid complicated the situation. The United States is 9th in GDP according to the World Bank. The Unites States Federal Government made decisions during COVID that were often times changed or ignored by individual States. This made dealing with COVID more difficult because there could not be one uniform plan for dealing with providing access to broadband internet, hardware and software the pandemic made necessary. China, on the other hand, is 81st in GDP according to the World Bank, but is the world’s most populous country. This means China is trying to get technology to 4 times as many people as the United States on 1/6th of the financial resources. Both countries had to deal with getting their students who were now learning remotely, usually from home, access to internet capable devices and an internet connection. Factor in some of the complications families had with connecting unfamiliar hardware with new software, and a lack of IT support, and there were a lot of students missing class time.

In China, TV stations provided “Classrooms on Air” via satellite where cell reception could not reach. With a bad combination of physical distance for some families from the nearest internet or cell connection, a lack of money for those families to pay for these resources even if they are available, and teachers responsible for large areas, 2 out of 10 rural students had no interaction with their teachers. (Li et al., 2020). US families, on the other hand had more resources in their neighborhoods but lacked money to purchase hardware, software or internet access. These families often resorted to public wifi for their children, but even that was an imperfect plan. Less places were open for seating due to COVID, and it meant the student was away from home most of the day. Younger children did not have that option to be left unsupervised for 8 hours a day. Teachers lack of preparedness was an issue for both countries. Teachers were used to teaching in-person with the student in the class. At home, the students were often distracted by other things in the house or on their phone. The style of presentation was also different and took some adjusting. Some teachers would teach a lesson, then set aside time to work individually with the students who needed help or had questions.

Despite online learning being used at the college level for over two decades, online education for K-12 was for most teachers and students, a completely new experience. Technology inequity is a two-fold problem. The first problem is access to the resources in the first place. The second problem is being able to afford these resources. The steps to providing equitable access to educational resources, both online and offline, is a four step process. 1. Develop a Systematic Technology Plan. 2. Liaise schools with local libraries. 3. Implement and Invest in Digital Tools that are Easily Accessible Offline to Promote Inclusiveness 4. Prioritize equity in Learning Initiatives..

Alhattab, S., & Thompson, G. (2021, March 2). Covid-19: Schools for more than 168 million children globally have been completely closed for almost a full year, says UNICEF. UNICEF. Retrieved April 16, 2022, from https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/schools-more-168-million-children-globally-have-been-completely-closed

Beaunoyer, E., Dupéré, S., & Guitton, M. J. (2020a). COVID-19 and digital inequalities: Reciprocal impacts and mitigation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 111, 106424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106424

Bergman, A. B., & Iyengar, J. I. (2020, April 8). How COVID-19 is affecting internet performance. Fastly. https://www.fastly.com/blog/how-covid-19-is-affecting-internet-performance

Brown, M.R., Higgins, K. & Hartley, K. (2001) Teachers and Technology Equity, Teaching Exceptional Children, 33(4), 32-39.

Bruder, I. (1989). Distance Learning: What’s Holding Back This Boundless Delivery System? Electronic learning, 8(6), 30-35.

Collis, V. C., & Vegas, E. V. (2022, March 9). Unequally disconnected: Access to online learning in the US. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/education-plus-development/2020/06/22/unequally-disconnected-access-to-online-learning-in-the-us/

China Internet Network Information Center. (2022). The 49th statistical survey report on Chinese Internet development. Accessed March 2022. https://www.cauc.edu.cn/jsjxy/upfiles/202203/20220318171634656.pdf

China Institute of Rural Education Development. (2020). Bridging the “digital divide” between urban and rural education, http://ire.nenu.edu.cn/info/1038/3274.htm

DRC. (2020). A survey on digital learning of students in less developed areas during the Covid-19. https://www.chinathinktanks.org.cn/content/detail/id/vdue1m37.

Fernandes, N. (2020). Economic Effects of Coronavirus Outbreak (COVID-19) on the World Economy. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3557504

Graham, M. (2011). Time machines and virtual portals: The spatialities of the digital divide. Progress in development studies, 11(3), 211-227.

Journell, W. (2007). The Inequities of the Digital Divide: Is E-Learning a Solution? E-Learning and Digital Media, 4(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2007.4.2.138

Khlaif, Z. N., Salha, S., Fareed, S., & Rashed, H. (2021). The Hidden Shadow of Coronavirus on Education in Developing Countries. Online Learning, 25(1).

Li, G., Zhang, X., Liu, D., Hao, X., Hu, D., Lee, O., … & Rozelle, S. (2021). Education and EdTech during COVID-19: evidence from a large-scale survey during school closures in China. Stanford REAP,https://fsi-live.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/education_and_edtech_during_covid-19-final-08032020.pdf

Liu, L., & zhao, H. (2020). Online education is abandoning poor students: an exploration of digital education inequality in China. DIGITAL CULTURE & EDUCATION, https://www.digitalcultureandeducation.com/reflections-on-covid19/abandoning-poor-students#

Liu, J. (2021). Bridging Digital Divide Amidst Educational Change for Socially Inclusive Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sage Open, 11(4), 21582440211060810.

Lynch, M. (2020, December 24). Remote learning is failing low-income and special needs kids. The Tech Edvocate. Retrieved April 12, 2022, from https://www.thetechedvocate.org/remote-learning-is-failing-low-income-and-special-needs-kids/

Macias, A., & Stephens, S. (2019). Intersectionality in the field of education: A critical look at race, gender, treatment, pay, and leadership. Journal of Latinos and Education, 18(2), 164-170.

MOE. (2020). Disrupted classes, undisrupted learning. January 30. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-01/30/content_5473048.htm

Nielsen, J. (2006). Digital divide: The three stages. Accessed 14th Jan 2021. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/digital-divide-the-three-stages/,

Papert, S. (1980). Chapter 1. In Mindstorms: Children, computers and powerful ideas (pp. 36–37). essay, Perseus.

Redmond, P., Heffernan, A., Abawi, L., Brown, A., & Henderson, R. (2018). An online engagement framework for higher education. Online Learning, 22(1), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i1.1175

Reiser, R.A. (2001) A History of Instructional Design and Technology: part I: a history of instructional media, Educational Technology Research and Development, 49(1), 53-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02504506

Servon, L.J. & Nelson, M.K. (2001) Community Technology Centers: narrowing the digital divide in low- income, urban communities, Journal of Urban Affairs, 23, 279-290. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/0735-2166.00089

The NCES Fast Facts. National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, a part of the U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). Retrieved April 11, 2022, from https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=46

Tiwari. P. (2021). COVID-19 and Online Learning in Rural China: Challenges, Impact, and Opportunities. Institute of Chinese Studies, 75. https://www.icsin.org/uploads/2021/08/02/a15b1f897867bf8d0089925c9f40d685.pdf

Van Dijk, J. A. (2006). Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings. Poetics, 34(4-5), 221-235.

Xinhua. (2020). This rural teacher walks 30 miles every day to collect and deliver homework during the epidemic period online classes. http://www.xinhuanet.com//mrdx/2020-04/24/c_139004337.htm

Zhong, R. (2020). Coronavirus Fight Lays Bare Education’s Digital Divide. The New York Times, https://cn.nytimes.com/technology/20200318/china-schools-coronavirus/dual/