4 Chapter 5: The transition of place-based learning communities for K-12 STEM teachers to social media

Professional learning communities before and during COVID-19

jolley63; moore4676; and evans2464

Introduction

Face-to-face learning communities have a long history in education. In the last decade, and most recently due to the shift online brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic many of these communities have transitioned to various online platforms. In this chapter, we will explore the history of learning communities and how learning communities and professional development (PD) has evolved prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. This chapter shows how social media learning communities such as Twitter’s #edchat can be used by K-12 Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) teachers in the mid-western United States as they explore various opportunities to enhance their professional development.

Research Question

How have learning communities (face to face and on social media) developed and evolved prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic to help K-12 STEM teachers access opportunities to enhance their professional development?

What are Learning Communities (LCs)?

Learning Communities are defined as a group of educators or professionals working together to achieve a shared goal and create knowledge (Trust, Krutka, & Carpenter, 2016). Learning communities go by many names such as Personal Learning Networks and Professional Learning Communities and they exist in many different modalities (e.g., face to face (F2F), online, synchronous, or asynchronous). In these communities, knowledge creation is often achieved through dialogue, evaluation, and reflection as community members identify and share strategies to solve problems faced. Members share resources such as lesson plans and teaching strategies and collaborate across departments (Flanigan, 2011). These communities offer new spaces for teachers to learn and grow as professionals as they access a diverse network of people and resources who are able to provide support (Trust, 2012). K-12 STEM Teacher LCs are often used to describe every imaginable combination of individuals with an interest in K-12 STEM education. The infographic below presents more descriptions of LCs and their variations.

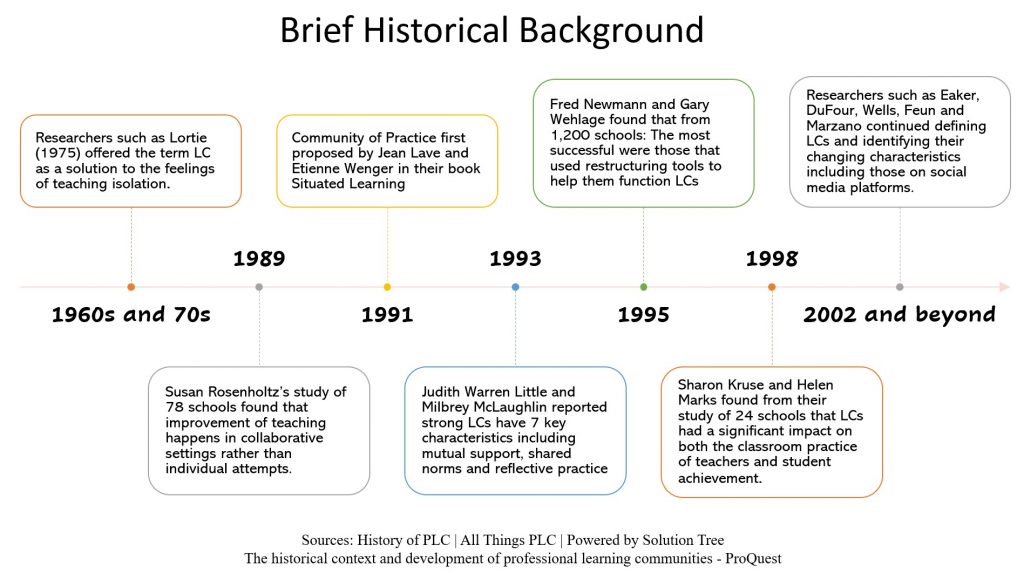

As LCs purpose and location change over time, educators participating in LCs are guided by the following principles: 1) Ensuring that students learn; 2) A culture of collaboration; and 3) A focus on results. LCs require hard work and the commitment of members in establishing and sustaining them as sustained participation has the potential to change the perception and future actions of members positively or negatively and can be a great asset for use in teacher education (DuFour, 2007). When K-12 STEM teachers use LCs to access strategies and a support system to improve teaching and learning they also encounter various challenges. These include: 1) It requires a great deal of time towards effective training (which is often not done) and 2) matching schedules for community members to meet is difficult given the types of everyday distractions of school issues (Fleck, 2012; Smith 2001). With these challenges in mind, LCs tend to struggle to be established and sustained however as seen in the timeline below they have a long history in education and are always seen as having significant impact on K-12 teacher’s development and student achievement.

Figure 3. Timeline showing development of learning communities since the 1960s. Click image to zoom.

As K-12 teachers continue using LCs to improve professional practice, one approach to addressing challenges faced with LCs and creating widely accessible and sustainable learning communities is forming and using LCs on social media platforms such as Twitter or Reddit (Xing and Gao, 2018; Goodyear, Parker, and Casey, 2019). The use of social media learning communities for teachers will be discussed in the next section.

Social Media Learning Communities (SMLCs)

What are Social Media Learning Communities?

SMLCs are learning communities accessed on platforms such as Twitter, Facebook or Reddit. SMLCs show great potential as they align with the need for using multiple tools outside of the formal classroom that can open the door for other forms of collaboration not yet explored in a place based setting (Greenhow et al., 2021). SMLC design suggests that purpose, scope, motivations to participate, and topics discussed range across communities and are essential in SMLC growth, maintenance, and sustainability (Hwang and Foote 2021). Exposure to the benefits of how these communities can increase member’s satisfaction, connection and create authentic knowledge that may help them take productive action in their real-life experiences is often stated as a benefit of moving and using LCs to social media platforms (Borge & Mercier, 2019). Initially, K-12 STEM teachers in SMLCs, may not be used to utilizing online tools to uptake information, and work with others to create new ideas in a public forum but the satisfaction they find in engaging in such flexible online interaction to create authentic knowledge may help them in completing their daily activities (Borge & Mercier, 2019). SMLCs serve many purposes for K-12 STEM teachers. SMLCs can accommodate a wide variety of artifacts (technological, instructional; Stahl et al. 2014) to stimulate collaborative learning and create a space where teachers can learn as a group while they build networks through shared meaning and artifact construction (Scardamalia and Bereiter, 2021) in a technology rich environment. SMLCs encourage collaboration leading to the creation, improvement, sharing, and advancing of ideas as K-12 teachers act or become expert-like and work on artifacts as they aim to achieve knowledge advancement (Scardamalia and Bereiter, 2021). SMLCs which prioritize knowledge building by all teachers/members, aim to demonstrate that created knowledge and artifacts is not the cognitive property of individuals but an outcome of group collaboration and can impact both individuals and all members (Stahl et al. 2014).

Benefits and Drawbacks of SMLCs

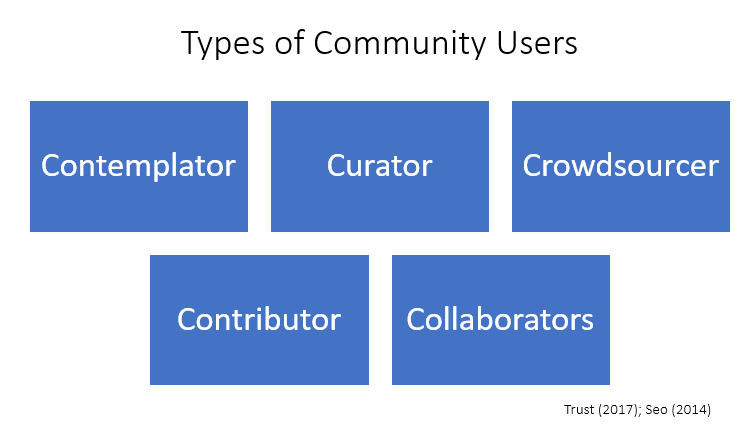

SMLCs with sustained group interactions looks to invite K-12 teachers who do not feel a strong sense of membership or feeling disconnected (Croft et al., 2010) create a sense of emergent online collective efficacy (Glassman et. al. 2021). In SMLCs K-12 STEM teachers can work with each other in non-hierarchical, non-linear fashion, creating new knowledge to address critical problems (Wagner, 2010). Other benefits of SMLCs for K-12 STEM teachers include: 1) SMLCs offer an open anywhere/anytime resource to members to share information and discuss problems synchronously and asynchronously which is often needed and important to the busy teacher; 2) SMLCs can allow K-12 STEM teachers to connect with peers or content experts by simply logging in compared to the difficulties faced accessing peers in face to face settings; 3) SMLCs offers a platform to reach out, quickly and easily, when they need help and 4) schools can offer PD and or meetings asynchronously on SMLCs which encourages greater completion/access at the convenience of the teacher (Trust & Prestidge, 2021; Seo, 2014). While there are clear benefits to well-constructed SMLCs, not all educators are on board with connecting and learning in the digital realm or navigating the fluid engagement amongst digital and in-person interfaces. The potential for social disconnection in SMLCs which merely provide information to users suggests the need for more active participation of K-12 STEM teachers in keeping the community engaging. In the figure below, we see the types of SMLC users that can exist in a community of K-12 STEM teachers and how their roles impact sustaining an active support system. Addressing the activities of each member with various requirements such as posting for continuing education credits can improve the impact of SMLCs for teachers. Some of the members we see in SMLCs are the contemplator or observers (read and think about posts), curator (collect and organize ideas), crowdsourcer (asks for information), contributor (write and responds), collaborators (reply and participates), and contributors (shares resources). These community users impact the development of SMLCs in various ways and proper training and active involvement by each creates a supportive and sustainable community which is needed for K-12 STEM teachers (Trust, 2017; Seo, 2014).

Figure 4. Types of learning community users as identified by Trust (2017) and Seo (2014).

Other challenges faced in SMLCs when K-12 STEM teachers are not actively engaged include members uptake (such as the curator) to take new ideas to try out in their practice rather than to share their experiences or collaborate with others in the community (Krutka, Carpenter, & Trust, 2016; Tsiotakis & Jimoyiannis, 2016). There is also 1) lack of time – K-12 STEM teachers must carve time out from their own personal schedules to participate in self-directed learning in SMLC compared to in-person settings, where participating in online spaces requires training; 2) confidence – teachers who were not confident interacting in online spaces tend to limit their actions to reading posts and observing others; 3) relationships – when teachers felt as though they had not developed strong relationships with individuals in a particular setting, they limited their interactions (Koslow & Pina, 2015), and 4) space dynamics – every space has unique members and features, including tools, activities, and user interfaces (for digital spaces), that influence the types of interactions that occur. Oftentimes, these features evolve based on changes in membership or members’ needs (Hernandez et al, 2017; Trust & Prestidge, 2021). Lastly, the presence of spam, like tweets promoting commercial products, can increase the signal to noise ratio among online learning communities, like those on Twitter #edchat, that can detract from their usefulness (Carpenter et al., 2020).

Designing SMLCs to support K-12 STEM teachers’ collaborative learning should focus on both individual agency and collective action in different learning contexts (Stahl & Hakkarainen, 2020). This will enable the formation of an active and successful community that can inform future pedagogies and practice to create more authentic classroom experiences and greater innovation (Scardamalia and Bereiter, 2021). One popular platform for SMLCs is Twitter, and this will be covered in the next section.

Introduction to Twitter and Twitter SMLCs

Twitter, an online news and social networking site, is among the top 3 social media platforms in the United States, with 206 million daily active users (Dean, 2022). The site was launched in 2006 after Jack Dorsey, co-founder, had the idea to create an SMS-based platform where users could share personal status updates, similar to texting (History.com Editors, 2021). Twitter is known as a microblogging platform due to its message size limitation of 280 characters or less and users can follow each other to expand their network and communicate with each other in real time using short messages called tweets. One unique feature of Twitter is the use of hashtags, words or phrases preceded by the pound symbol (ex. #edchat, #edtech, #STEM). Hashtags serve as indicators that content belongs to specific categories and makes content discoverable for users and algorithms (Olafson, 2021). Hashtags are a way to organize content into specific topics, themes, or conversations, as can be seen in the embedded tweet below, and can help build communities around those same topics, themes, or conversations. For example, teachers interested in STEM education may tag their tweets with #STEM to keep conversations related to STEM as one topic. Anyone interested and searching #STEM would have access to those tweets and ideas.

1st question of February's #InnovatingPlay slow chat on the topic We Love Coding!!

Q1 What are the benefits of giving our little learners the opportunity to explore computer science through coding?#satchat #satchatwc #edchat #gafe4littles #edtech #K2canToo #TwitterEDU #STEM pic.twitter.com/EE5DOWlgAt

— Christine Pinto (@PintoBeanz11) February 5, 2022

Twitter communities can be impactful in education as educators can learn more about teaching, professional development, technology, education policy, or any other interests they may have. In the next section we cover the popular Twitter learning community #edchat.

Introduction to Twitter #Edchat

In teacher education, very few well known successful, technology driven communities exist. This has been especially problematic, recently, as teachers look to navigate students/community educational needs in the COVID pandemic. Currently, there are tools promoting educational online communities for sharing information such as #edchat on Twitter, where educators can come and share information and experiences. Twitter chats afford educators with opportunities to connect with other educators, exchange ideas, get advice, find novel resources, and learn about innovative practices (Zaino, 2016). #Edchat is the hashtag for a weekly moderated Twitter chat where educators and other individuals interested in education meet virtually to discuss all things education. #Edchat was founded in July 2009, by education professionals Shelly Terrell, Tom Whitby, and Steven Anderson (Anderson, 2012). It started out as a series of educational conversations between the three professionals that grew into a larger conversation between educators all over the country. To learn more about and explore various aspects of #edchat, click the image below (Figure 5).

The video below, with Alec Couros, is an excellent resource that further describes Twitter’s role in education. Twitter chats are live conversations on Twitter focused on specific topics where educators meet online to engage in conversations by sending out tweets using a designated hashtag. Twitter chats occur during designated times on designated days and most chats last for an hour. Educators can participate in conversations that have a broad focus on education or a narrower focus on certain subjects, grade levels, and teaching strategies. Some popular education hashtags include: #edchat, #edtechchat, #edmodochat, #hseduchat, #kidsdeserveit, #teacherprepchat, #educoach (Zaino, 2016).

Evolution of #Edchat Due to COVID-19

Twitter #Edchat use by Teachers Before COVID – 19

Twitter is one of the most used social media platforms for teacher professional development (PD) and hashtags like #edchat, commonly used for PD, consistently sustains a high volume of participants with more than 100,000 tweets monthly (Bruguera et al., 2019, Staudt Willet, 2019). Although research suggests that the three primary uses for Twitter in education in pre-pandemic years are communication with students and families, class activities, and professional development, PD has been found to be the most popular (PD; Carpenter & Krutka, 2014). Teachers prefer Twitter for PD because it provides immediate support where teachers can ask questions and react to others in real time; it can be personalized to meet a teacher’s professional needs through hashtags specifying topics, and it allows teachers to connect with each other regardless of time and space (Carpenter & Krutka, 2014).

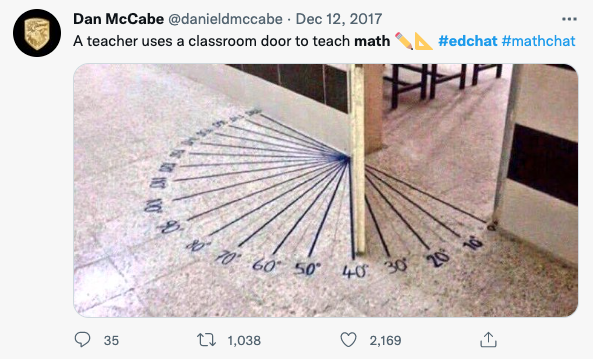

In addition to professional development, teachers reached out to Twitter #edchat for various other reasons in the pre-pandemic years. First, teachers used Twitter #edchat to battle isolation (Staudt Willet, 2019). This was especially true for teachers who were located in rural areas or were the only educator within a subject in their school. One high school math teacher reported using Twitter to create a mentoring network of teachers to help support career development (Risser, 2013). Twitter #edchat was also used by teachers to find innovative ideas or resources to help with lessons (as shown in the Twitter thread below). Lastly, it was used to connect and network with other teachers around the country and world (Staudt Willet, 2019).

Dan McCabe [@danielmccabe].(2017, December 12) A teacher uses a classroom door to teach math. Twitter. https://twitter.com/danieldmccabe/status/940778111871934464?s=20&t=WD-8LR4vxXfxSYYtixjORQ

Twitter #Edchat use by Teachers During COVID – 19

The worldwide COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 resulted in large scale disruptions with business closures, emergency remote learning, and physical distancing in public locations. To navigate the transition to remote learning and teaching, K-12 teachers in the United States turned to social media for support (Carpenter et al., 2020). Due to the educational system disruptions caused by the pandemic and the move to remote instruction, districts did not have enough time to professionally prepare teachers for the challenges they were about to face in emergency remote teaching (Greenhow et al., 2021). The pandemic increased demands for just-in-time teacher professional development (PD) but social media, including Twitter, provided some relief to those demands (Carpenter et al., 2020).

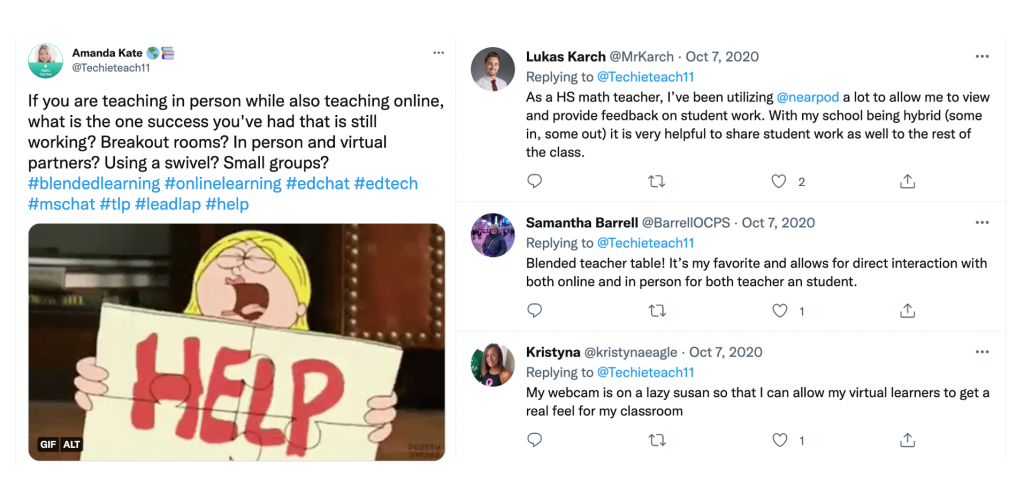

As mentioned previously, professional development was one of the most popular uses of Twitter #edchat before the pandemic (Carpenter & Krutka, 2014) and the pandemic increased demands for it (Carpenter et al., 2020). So, what differences were there with teachers’ use of Twitter #edchat between pre-pandemic and pandemic years? In their study Greenhow et al., (2021) did a quantitative analysis of over a half million Twitter #edchat tweets, content analysis of 1054 question tweets from teachers and 4 interviews and found that the overall the number of tweets did not change between pre-pandemic and pandemic years, but the content within #edchat did. During the pandemic, more novel hashtags were introduced relating to current events, like #remotelearning and #distancelearning alongside #edchat (Greenhow et al., 2021) compared to the online voting on current issues done before COVID-19 (Britt & Paulus, 2016). This change in content suggested a shift in conversation took place, as needed, and reflected a form of PD flexible to teachers’ professional needs, interests, and goals. Another significant difference in social media use during the pandemic was that teachers began asking for help and access to free classroom resources from other teachers whose schools were further along into the transition to teaching remotely (Greenhalgh, 2021; Greenhow et al., 2021). Lastly, topics dealing with remote learning and math in the sense of distance learning became dominant during COVID-19 as compared to pre-pandemic years (Greenhow et al., 2021).

Overall, teachers reached out to Twitter #edchat for PD needs before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The main difference being in content, where teachers reached our specifically for help with remote learning or COVID-19 related topics during the pandemic. Twitter #edchat provided them with insights into what other teachers were implementing during COVID-19 (Figure 4), support for any challenges or concerns they tweeted about, and collaboration opportunities with individuals beyond their school, state and cities (Greenhalgh, 2021; Greenhow et al., 2021).

Professional Development on SMLCs

LCs can both improve student learning and the professional growth of teachers leading to improved teaching and learning (McLaughlin & Talbert, 2006). In 1996, the U.S. Department of Education recommended that school districts set aside 30 percent of their technology budgets for staff training and development. As the department noted at the time, “If there is a single overarching lesson that can be culled from research about teacher professional development and technology, it is that it takes more time and effort than many anticipate.” (Consortium for school networking, 2001). Many student deficits arise with teachers who are unaware and unlearned in proper situational pedagogies needed for online engagement (as needed in the COVID-19 pandemic) and improving students’ knowledge and retention. Some teachers are also unknowledgeable of how to integrate instructional resources available for improving students’ knowledge and retention and for many schools, technology difficulties is often marred by six general barriers such as , scarce resources and inadequate knowledge and skills (Hew & Brush, 2007).

Teachers alienation and feeling unprepared (Hassall & Lewis, 2017) can incite teacher resistance from implementing best practices in new online spaces (Kelly, 2014). In a perfect world, teachers can use various approaches to create effective instructional content (Tang, 2020) that make lessons engaging and interactive as they aim to increase students’ interest and academic achievement. They can also transform any curriculum to accommodate their individual contexts regardless of school culture (Lin & Tang, 2017; Tang & Bao, 2020). These approaches are still needed in this new era of schooling and can be addressed with access and use of PD available on SMLCs (Trust & Prestidge, 2021).

Designing PD for SMLCs

High-quality professional development is a central component in improving K-12 STEM education. What attracts teachers to professional development, is their belief that it will expand their knowledge and skills, contribute to their growth, and enhance their effectiveness with students (Guskey, 2002). K-12 STEM teachers want specific, concrete, and practical ideas that directly relate to the day-to-day operation of their classrooms (Fullan & Miles, 1992). There are, however, many facets to PDs that make it difficult to execute well. PD especially those online and asynchronous, need continuous revision as they become outdated and irrelevant quickly. Another issue that poses a challenge regarding what K-12 STEM teachers learn in PD sessions is consistency for what is translatable as practical application in the classroom (Xing & Gao, 2018; Davis, 2015; Rosell-Aguilar, 2018). PD designed for SMLC should be proactive and situational, not reactive. PD modules created for K-12 STEM teachers on SMLCs can make a successful model for integration in schools and districts ad they are personalized, updated, maintained, 24/7 accessible, and that opportunities exists to reach teachers across a variety of contexts and improve professional practice on a large scale (Xing & Gao, 2018; Davis, 2015; Rosell-Aguilar, 2018). PD content, implementation, outcomes, and evaluation are pursuant to local teaching practices and district policies.

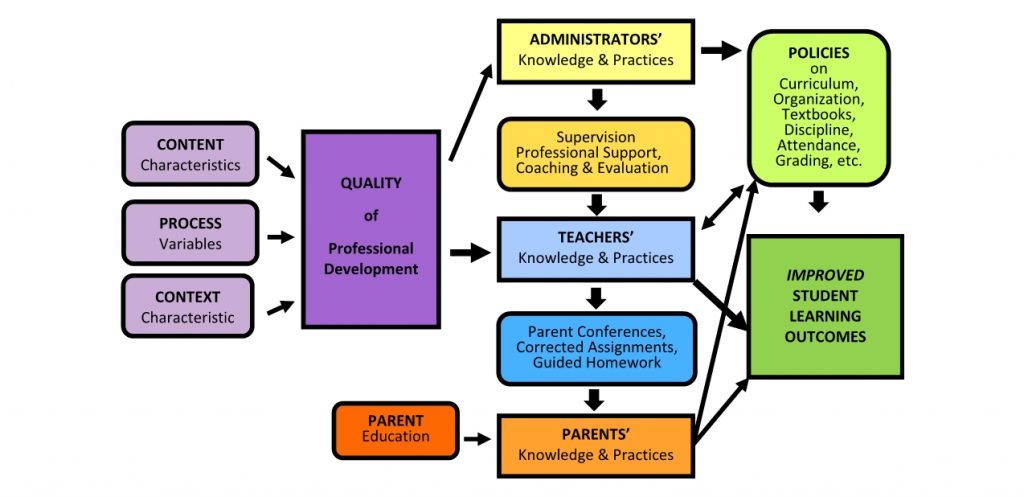

The figure below, based on Guskey’s (2002) model, shows the relationship between the different areas such as content and learning outcomes and the many persons involved in the planning, implementation and evaluation of PD. These relational elements should evolve as PDs transition from physical spaces to SMLCs. These include the consideration of self-paced or asynchronous learning as seen on alternative platforms and how K-12 STEM teachers access these PDs on SMLCs and these will be discussed in the next sections.

Figure 8. A representation of the relationship between the different areas and persons involved in the executing PD. Click image to zoom.

Alternative Platforms prior to COVID-19

Observations within face-to-face classroom settings has been a traditional format for pre- and in-service teacher PD. Additionally, PD workshops can be periodic, collective for specific groups such as only STEM K-12 teachers, or as single sessions where teachers review pedagogical practices to improve their professional practice and teaching and learning (Avalos, 2011). Emerging with the need for new approaches to PD, multimedia has garnered attention for more customized situational andragogy as they also prove effective for K-12 educators and their professional learning. In response, prior to COVID-19, many PDs have been integrated into schools Learning Management Systems (LMS) and they increase accessibility for teacher engagement, training and facilitation between scheduled face to face workshops (Avalos, 2011). Utilizing these platforms enables teachers to review traditional methodologies, gain exposure to new techniques, and engage these new techniques within their classrooms according to respective district policies. These have worked well in the past however the COVID-19 pandemic and the closure of schools has made this approach more difficult especially for new teachers, those in challenging fields like STEM or in areas of the mid-west USA with limited access to resources. Prior to COVID-19, an internet alternative was mostly offered for attending learning sessions. But since the pandemic, teachers facing disparities in rural communities and districts, because of limited broadband capability, are challenged with connection and access issues. Broadband and Wi-Fi service are the key mediums for teachers to connect and collaborate in any virtual PD session. This is one example of why some teachers started translating their PD learning of traditional pedagogies to SMLCs and other approaches. Expanding broadband access, improving internet speeds, and reducing baseline plan price to improve affordability are important visons for education and are covered in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act or H.R. 3684, which was signed into law in November, 2021.

Establishing Principles to Multifaceted PD during COVID-19

In the 1980s, educator and practitioner, Malcolm Knowles (shown in photo), popularized Andragogy, “the art and science of helping adults learn,” (Teal Center, 2019) with a six-principled approach. These principles or assumptions include, self-direction, utilizing prior experience for learning, are ready to learn, wanting to apply knowledge immediately, learn best through problem-based learning, and have intrinsic motivations for learning. Knowles contrasts andragogy as a process model for adult learning to pedagogy, a content model for teaching children. It is through this lens that current PD modules are designed for educators as they aim to improve professional practice. From traditional structures that use in-class observation, to LMS’s integration of technology and now virtual workshops on Zoom’s multimedia platform or learning ecosystems as a multifaceted approach, PD is a necessary construct, that must continue evolving toward management of situational learning by establishing multidimensional strategies to address problems in this current educational environment.

Early in 2012, the Office of Education Technology released a seventy-six-page brief with a small acknowledgment, that current research does not explain in an exact definition of how practitioners can effectively navigate online interactions with instruction. Ineffective budgeting projections affecting PD, and the non-uniformity of Andragogy for online learning, continued to challenge educators because of the rapidly increasing demands for online PD sessions. In the Handbook of Research on Transforming Teachers Online Pedagogical Reasoning, Teachers College researchers, Ellen Meier and Caron Mineo, discuss “Pedagogical Challenges During COVID”, highlighting PD design and transforming professional engagement practices as the top two challenges (2021, pp. 88-93). It is within their discussion that contextual teaching designs are presented on how pedagogy should transform to become more reflective of classroom realities or situations and how PD should adapt accordingly. Likewise, a critical analysis of a STEM workshop sponsored by the National Science Foundation (NSF), explains the multiple solutions approach and how, “real-world problems can be solved through multiple solutions, not just one” but this week long PD allowed teachers to practice integrating contextual teaching design into K-12 STEM courses as it relates to real-world problems and student life experiences outside of school but this became a rather difficult goal to achieve during the COVID-19 pandemic (Dare & Ring-Whalen, 2021).

In addition to the inconsistent use of principles, ineffective designs, and costs, other factors affecting face to face PD and requiring the transition to SMLCs are an evolving set of constructs, which vary between districts and states. The Federal STEM Education Strategic Plan released in October 2019, adds that authentic learning experiences should be created with a well-prepared workforce having lifelong access to proper resources (Droegemeier, 2019). These and other implications became more apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic, as the norms were stressed and stretched, through forced transitions to online learning, and the subsequent requirements of hybrid learning situations. In this next section, a learning ecosystem is explained through a K-12 STEM program which engages PD for teachers, using SMLCs to discuss pre-pandemic constructs and COVID-19 adjustments.

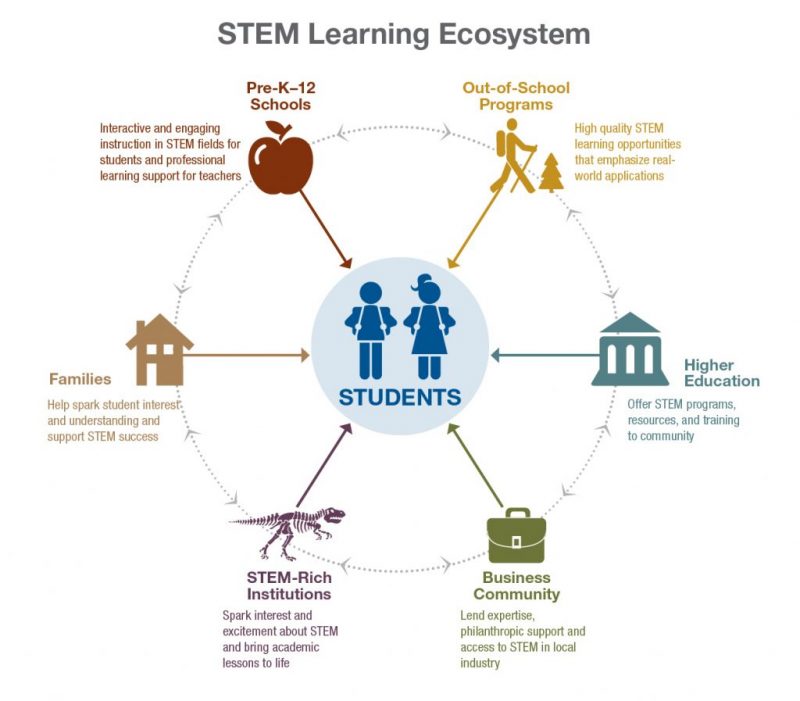

The future of K-12 STEM PD: Learning Ecosystems

Prior to the pandemic, LCs were utilized by STEM supporters to mirror how a STEM Learning Ecosystem makes PD accessible, and collaborative for teacher participants. K-12 STEM educators are specifically the focus of many legislators and administrators in this decade, as they aim to prepare students for a technologically advancing workforce. STEM Learning Ecosystems was launched and hosted at the White House in 2015 and it was anchored through twenty-seven groups to create virtual learning communities for individuals, STEM rich establishments like museums, PK-12 school systems, higher education entities and community learning centers. The video below shows, teachers convened, collaborated and became empowered with a structured ecosystem of peers and resources. They had access to online resources to establish outreach and support and had open-access to STEM providers, supporters and interested groups to build and engage ongoing collaboration opportunities. With this approach, STEM teachers are able to glean from a pool of resources and essentially broaden their own PD proactively or as needed. The STEM learning Ecosystem Community of Practice (SLECoP) maintains an online presence since 2016 using #SLECoP on Twitter which also links directly to their community website, stemecosystems.org. #SLECoP community members share links for webinars and virtual meetings with professional activities, legislation and convention discounts and this has been very relevant and active since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Having a relevant and relatable ecosystem of information and accessible opportunities improves PD interests for teachers and could direct the future of SMLC PDs. For example, a teacher may read a tweet about the NSF and how it is helping support and promote science interests into award-winning products, then link to the website, and webinar for the most current details. Professional supporters from community colleges share resources as do SLECoP partners while discussing State Policy issues which affect teachers and PD and this can not only improve access but overall professional practice of K-12 STEM teachers. Teachers are also able to keep updated in these SMLCs as PD sessions are made available by SLECoP where their team updates their Twitter page regularly with the latest legislative efforts to increase STEM funding and PD to boost STEM workforce and job training. In the figure below, the Department of Education uses this design model to show how a learning ecosystem works to help support professional development within and outside STEM K-12 classrooms.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic and its overwhelming impact on engagement, educators using SMLCs are making strides to boost professional development, Heutagogical content (improving self-paced study and asynchronous learning), and broaden established frameworks (Meier, 2018). Professional Development interests and emerging strategies are aligning, from the most traditional settings to multifaceted approaches such as PD on SMLCs, to prepare teachers, and improve their professional growth. Expanding to one hundred individual communities in forty states (also in Kenya, Israel, Mexico, Canada) the current #SLECoP is an approach that continues to engage its members as the possible future of PDs in SMLCs and now that COVID-19 restrictions are reducing, SLECoP continues to share learning pedagogies for various K-12 STEM settings which cover traditional and/or virtual engagement. Community and business partnerships that create networking opportunities for teachers on SMLCs can only help improve teachers’ professional practice as they work to meet needs of their students.

Conclusion

In this chapter we identified how the need to support teachers was the catalyst for creating learning communities initially face to face as early on record as the 1960’s. PDs have evolved tremendously since then and there has been the inclusion of new and innovative methodologies and technologies now as teachers in different regions around the world use platforms such as Twitter to access peers and the resources to improve professional practice as well as teaching and learning. PDs on SMLCs established prior to the COVID-19 pandemic were presented as alternative resources and a boost to embrace technology but since COVID-19s and the continued navigation of this pandemic, SMLCs have become established platforms for PD, educational resources, and networking opportunities to build multidimensional partnerships for teachers and administrators. From this chapter we hope readers can see the potential of PDs on SMLCs and the impact access to resources, peers, content experts and a strong support system on these platforms can have on their professional careers.

References

Anderson, S. (2012, March 14). A brief history of #Edchat. A Brief History Of #Edchat. Retrieved April 27, 2022, from http://blog.web20classroom.org/2012/03/brief-history-of-edchat.html

Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teaching and teacher education, 27(1), 10-20.

Borge, M., & Mercier, E. (2019). Towards a micro-ecological approach to CSCL. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 14(2), 219-235.

Britt, V. G., & Paulus, T. (2016). “Beyond the four walls of my building”: A case study of# Edchat as a community of practice. American Journal of Distance Education, 30(1), 48-59.

Bruguera, C., Guitert, M., & Romeu, T. (2019). Social media and professional development: a systematic review. Research in Learning Technology, 27, 1-18. 10.25304/rlt.v27.2286.

Carpenter, J. P., Krutka, D. G., & Kimmons, R. (2020). # RemoteTeaching &# RemoteLearning: Educator tweeting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 151-159.

Carpenter, J.P., & Krutka, D. G. (2014). How and Why Educators Use Twitter: A Survey of the Field. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 46(4), 414-434. 10.1080/15391523.2014.925701.

Carpenter, J.P., Staudt Willet, K.B., Koehler, M.J. et al. Spam and Educators’ Twitter Use: Methodological Challenges and Considerations. TechTrends 64, 460–469 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-019-00466-3

Consortium for school networking (2001). A Briefing Paper on School District Options for Providing Access to Appropriate Internet Content

Croft, A., Coggshall, J. G., Dolan, M., & Powers, E. (2010). Job-Embedded Professional Development: What It Is, Who Is Responsible, and How to Get It Done Well. Issue Brief. National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality.

Dare, E. A., & Ring-Whalen, E. A. (2021). Eliciting and refining conceptions of STEM education: A series of activities of professional development. Innov. Sci. Teach. Educ, 6, 1-19.

Davis, K. (2015). Teachers’ perceptions of Twitter for professional development. Disability and rehabilitation, 37(17), 1551-1558.

Dean, B. (2022). How Many People Use Twitter in 2022? [New Twitter Stats]. Backlinko. https://backlinko.com/twitter-users.

Droegemeier, K. (2019). (rep.). 2019 Stem Progress Report. U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved March 17, 2022, from https://www.ed.gov/sites/default/files/documents/stem/2019-stem-progress-report.pdf.

DuFour, R. (2007). Professional learning communities: A bandwagon, an idea worth considering, or our best hope for high levels of learning?. Middle school journal, 39(1), 4-8.

Flanigan, R. L. (2011). Professional learning networks taking off. Education Week, 31(9), 10–12.

Fleck, J. (2012). Blended learning and learning communities: opportunities and challenges. Journal of Management Development.

Fullan, M. G., & Miles, M. B. (1992). Getting reform right: What works and what doesn’t. Phi delta kappan, 73(10), 745-752.

Glassman, M., Kuznetcova, I., Peri, J., & Kim, Y. (2021). Cohesion, collaboration and the struggle of creating online learning communities: Development and validation of an online collective efficacy scale. Computers and Education Open, 2, 100031.

Goodyear, V. A., Parker, M., & Casey, A. (2019). Social media and teacher professional learning communities. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(5), 421-433.

Greenhalgh, S. P. (2021). Differences between teacher-focused Twitter hashtags and implications for professional development. Italian Journal of Educational Technology, 29(1), 26-45.

Greenhow, C., Staudt Willet, K. B., & Galvin, S. (2021). Inquiring tweets want to know: # Edchat supports for #Remote Teaching during COVID‐19. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 1434-1454.

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and teaching, 8(3), 381-391.

Hassall, C., & Lewis, D. I. (2017). Institutional and technological barriers to the use of open educational resources (OERs) in physiology and medical education. Advances in physiology education, 41(1), 77-81.

Hernández, J. B., Chalela, S., Arias, J. V., & Arias, A. V. (2017). Research trends in the study of ICT based learning communities: a bibliometric analysis. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(5), 1539-1562.

Hew, K.F. & Brush, T. (2007). Integrating Technology into K-12 Teaching and Learning: Current Knowledge Gaps and Recommendations for Future Research. Educational Technology Research and Development, 55(3), 223-252. Retrieved March 1, 2021 from https://www.learntechlib.org/p/67598/.

History.com Editors. (2021). Twitter launches. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/twitter-launches.

Hwang, S., & Foote, J. D. (2021). Why do people participate in small online communities?. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(CSCW2), 1-25.

Kelly, H. (2014). A path analysis of educator perceptions of open educational resources using the technology acceptance model. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(2), 26-42. doi:10.19173/irrodl.v15i2.1715

Krutka, D. G., Carpenter, J. P., & Trust, T. (2016). Elements of engagement: A model of teacher interactions via professional learning networks. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 32(4), 150-158.

Koslow, A., & Piña, A. (2015). Using transactional distance theory to inform online instructional design. Instructional Technology, 12(10), 63–72.

Lin, Y. J., & Tang, H. (2017). Exploring student perceptions of the use of open educational resources to reduce statistics anxiety. Journal of Formative Design in Learning, 1(2), 110–125. doi:10.1007/s41686-017-0007-z

McLaughlin, M. W., & Talbert, J. E. (2006). Building school-based teacher learning communities: Professional strategies to improve student achievement (Vol. 45). Teachers College Press.

Olafson, K. (2021). How to Use Hashtags in 2021: A Quick and Simple Guide for Every Network. https://blog.hootsuite.com/how-to-use-hashtags/.

Risser, H. S. (2013). Virtual induction: A novice teacher’s use of Twitter to form an informal mentoring network. Teaching and Teacher Education, 35,25–33.

Rosell-Aguilar, F. (2018). Twitter: A professional development and community of practice tool for teachers. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 1.

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2021). Knowledge building: Advancing the state of community knowledge. In International Handbook of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning (pp. 261-279). Springer, Cham.

Seo, K. (2014). Professional learning of observers, collaborators, and contributors in a teacher-created online community in Korea. Asia Pacific journal of education, 34(3), 337-350.

Smith, B. L. (2001). The Challenge of Learning Communities as a Growing National Movement. Peer Review.

Stahl, G., Ludvigsen, S., Law, N., & Cress, U. (2014). CSCL artifacts. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 9(3), 237–245.

Stahl, G., & Hakkarainen, K. (2020). Theories of CSCL. To appear. International handbook of computer supported collaborative learning. London: Springer.

Staudt Willet, K. B. (2019). Revisiting how and why educators use Twitter: Tweet types and purposes in #Edchat. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 51, 273– 289. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391 523.2019.1611507

Tang, H. (2020). A qualitative inquiry of K-12 teachers’ experience with open educational practices: Perceived benefits and barriers of implementing open educational resources. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 21(3), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v21i3.4750

Tang, H., & Bao, Y. (2020). Social justice and K–12 teachers’ effective use of OER: A cross-cultural comparison by nations. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2020(1). doi:10.5334/jime.576

Teal center fact sheet no. 11: Adult learning theories. LINCS. (2019, April 8). Retrieved March 17, 2022, from https://lincs.ed.gov/state-resources/federal-initiatives/teal/guide/adultlearning

Trust, T. (2012). Professional Learning Networks Designed for Teacher Learning. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 28(4), 133–138.

Trust, T., Krutka, D. G., & Carpenter, J. P. (2016). “Together we are better”: Professional learning networks for teachers. Computers & education, 102, 15-34.

Trust, T. (2017). Using cultural historical activity theory to examine how teachers seek and share knowledge in a peer-to-peer professional development network. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33(1), 98-113.

Trust, T., & Prestridge, S. (2021). The interplay of five elements of influence on educators’ PLN actions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 97, 103195

Tsiotakis, P., & Jimoyiannis, A. (2016). Critical factors towards analysing teachers’ presence in on-line learning communities. The Internet and Higher Education, 28, 45-58.

Wagner, T. (2010). The global achievement gap: Why even our best schools don’t teach the new survival skills our children need-and what we can do about it. ReadHowYouWant. com.

Xing, W., & Gao, F. (2018). Exploring the relationship between online discourse and commitment in Twitter professional learning communities. Computers & Education, 126, 388-398.

Zaino, J. (2016). Teachers Join Education Twitter Chats to Learn, Collaborate, and Grow. Hey Teach!. https://www.wgu.edu/heyteach/article/teachers-join-education-twitter-chats-learn-collaborate-and-grow1612.html.