Chapter 13: RESEARCH STUDY | Violence Against Sex Trafficked Women: Implications for Healthcare Settings

Contributing Authors

Jacquelyn C.A. Meshelemiah, PhD, Professor[1] | Sat Kartar Khalsa, MD, Resident[2]

Hannah R. Steinke, MSW, Doctoral Student, Graduate Research Associate[3]

Sharvari Karandikar, PhD, Professor, Associate Dean of Academic Affairs[4]

Ran Hu, PhD, Assistant Professor[5]

ABSTRACT

Sex trafficking severely impacts the overall health of victims both in the short- and long- term due to extreme interpersonal violence. This retrospective study aimed to examine how formerly sex-trafficked women presented in medical settings during their ordeals and to offer recommendations for improving healthcare experiences for women in similar situations. The research questions addressed were: 1) What are the medical histories of formerly sex trafficked women? and 2) What were their healthcare experiences?

Fifty survivors of sex trafficking from a large Midwestern state in the United States were interviewed about their healthcare experiences. Data were collected via telephone or Zoom using a semi-structured interview guide. The analysis employed reflexive thematic analysis, a stepwise analytical approach. Participants reported: 1) a wide range of chief complaints by organ system resulting from interpersonal violence, 2) varied feelings of being judged when seeking healthcare, 3) persistent drug use while trafficked, and 4) a lack of identification by healthcare providers. Although most participants felt providers should have recognized signs of trafficking, few were identified as trafficked patients by healthcare professionals. Recommendations for practice and policy include enhancing education for healthcare providers on sex trafficking, as well as implementing multidisciplinary teams in healthcare settings.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Define sex trafficking.

- Comprehend the various forms of violence experienced by trafficked women that necessitate healthcare visits.

- Recognize the significance of healthcare access for women who have been trafficked.

Key Words: sex trafficking, chief complaints, complications by organ system

Introduction

Sex trafficked persons are subjected to interpersonal violence. According to the World Health Organization (2024), interpersonal violence refers to the intentional use of physical force or power (threatened or actual) between individuals at the family/partner (e.g., child, partner, or elder) or community levels (e.g., acquaintance or stranger). It can be physical, sexual, or psychological in nature as well as involve deprivation or neglect. Trafficked people tend to experience violence on both levels and in oftentimes in serious forms—sometimes to the point of being life threatening or resulting in fatalities (Ricci, 2017). Outside of fatalities, some of the most extreme consequences of interpersonal violence include health consequences.

Health consequences of trafficking include traumatic injuries caused by weapons or other foreign objects (Zimmerman et al., 2011), dental disease (Macias-Konstantopoulos, 2016), mental disorders (Saunders & Harris, 2019), malnutrition (Lederer & Wetzel, 2014), gastrointestinal issues (Ertl et al., 2020), drug misuse (Meshelemiah et al., 2018), cardiovascular conditions (Ertl et al., 2020), neurological issues (Menaker & Franklin, 2015), and genitourinary problems (e.g., gynecological, reproductive, STIs, etc.) (Lederer et al., 2023). As seen here, the consequences of violence on the health of trafficked people include a range of psychological, drug-related, and physical conditions. Sex trafficking significantly affects the physical and mental health of victims, both in the short and long term, due to the violence and trauma inherent in these situations (Lederer & Wetzel, 2014). Additionally, delays in seeking medical care or untreated health conditions contribute to persistent health issues within this population (Ades et al., 2019; Lederer & Wetzel, 2014; Macias-Konstantopoulos, 2016). Yet, this group of individuals fail to receive equitable healthcare services.

According to the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), sex trafficking is the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, obtaining, patronizing, or soliciting of a person for the purposes of a commercial sex act, in which the commercial sex act by the adult is induced by force, fraud, or coercion (Pub. L. No. 106-386). It is these elements of force, fraud, and coercion that often result in the need for health services for trafficked people. Lederer and Wetzel (2014) found that 87.8% (n = 98) of the women in their 2012 sample sought healthcare while being trafficked. Similar findings have been reported among other trafficked populations (Lederer et al., 2023; Macias-Konstantopoulos et al., 2013; Rajaram & Tidball, 2018; Vo et al., 2023)—suggesting that healthcare providers have the potential to play a critical role in identifying sex trafficked women. To do this though, sex trafficked victims and survivors must be identified in healthcare settings, which often does not occur (Saunders & Harris, 2019; Shandro et al., 2016; Shekhar & Macias-Konstantopoulos, 2023).

Social Determinants of Health

According to the World Health Organization, biased social, economic, and political mechanisms result in socioeconomic apartheid whereby people are stratified by their income, education, job or occupation, gender, race/ethnicity and other factors. Consequently, these social hierarchal boxes result in specific determinants of health statuses that lead to differential exposures and vulnerabilities to health-compromising conditions (WHO, 2010). The consequences of these types of health inequities originating with social determinants of health (SDOH) can be far-reaching and long-term for trafficked persons. As a public health framework, social determinants of health, is appropriate and a needed narrative on marginalized women who are sex trafficked if health equity is to be achieved for this population. (See Box A for more details on health equity.)

Karandikar et al. (2024) utilized social determinants of health in their examination of women and children in India’s red-light brothel districts to contextualize the social (e.g., low caste, stigmatized profession), economic (indigence, food insecurity), and political (national lockdown during the most COVID-19 pandemic) devaluation of these groups of individuals and the inequities they face. Robichaux and Torres (2022) assert that a public health approach to caring for trafficked patients is critical to their equitable and just access to healthcare. They emphasize the importance of establishing therapeutic relationships with trafficked patients and utilizing interdisciplinary teams in healthcare settings. Last, they contend that human trafficking is a human rights violation that erodes one’s right to health.

This study sought to examine the medical history and healthcare-seeking experiences of women who were sex trafficked in the United States. The goal of this retrospective study was to examine the ways in which formerly sex-trafficked women presented in medical settings while being trafficked to provide recommendations to improve the healthcare experiences of similarly situated women—starting with identification. Specifically, the research questions in this study were: 1) What are the medical histories of formerly sex trafficked women? and 2) What were the healthcare experiences of these women? Additionally, the authors of this study propose a comprehensive approach to healthcare access and treatment for trafficked women, taking into account social, economic, and political barriers rooted in social determinants of health.

Methods

Procedures

The study protocol for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Ohio State University. Recruitment for this study took place using a purposive sampling method whereby women were recruited from a safehaven for formerly trafficked persons using a flyer. This method allowed the researchers to target participants who would be good sources of information (Krysik & Finn, 2013; Rajaram & Tidball, 2018). This nonprobability snowball sampling method involved starting with known participants in the safehaven who met eligibility criteria and then asking for referrals to other women who met eligibility criteria (Dane, 2011; Krysik & Finn, 2013). Verbal informed consent was acquired prior to interviews. Interviews were conducted between November 2020 and January 2021 via Zoom or telephone. Interviews lasted approximately 90 minutes. Women were compensated $100 for participating and assigned pseudonyms to protect their identities.

Participants

Inclusion criteria for the study included being 18 years or older, self-identifying as a sex-trafficked woman according to the Trafficking Victims Protection Act and being English-speaking. Participants also had to have a history of seeking out healthcare and/or social services.

Measures

For the purposes of this study, survivors were asked 15 sociodemographic questions related to age, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, marital status, education, employment status, help-seeking histories, age first trafficked, and years trafficked. They were also asked 14 questions related to their experiences of violence and medical history, and 14 questions related to healthcare experiences. Sample questions included, 1) Have you ever been knocked unconscious (“knocked out”)? What happened?; 2) Were you ever threatened or physically hurt because you wouldn’t perform a sexual act?; 3) What medical conditions have you had in the past?; 4) Overall, what ailments, medical conditions, or injuries were directly tied to being a trafficking victim?; 5) How many times did you see a healthcare provider while you were trafficked?; 6) Were there any times that you avoided going to a healthcare provider out of fear or any other reason? Why?; and 7) Did anyone ever detect or become suspicious that you were a victim at the time of healthcare utilization?

Data Analysis

The data in this study were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis. This approach was used because it provided a flexible approach to understanding the lived experiences of survivors while obligating the researcher to acknowledge their subjectivity, reflect on their positionality, and engage repeatedly with the data. According to Braun and Clarke (2022), reflexive thematic analysis includes a stepwise approach that includes 1) data familiarization; 2) coding; 3) generating initial themes; 4) developing and reviewing themes through an iterative process; 5) refining, defining, and naming themes; and 6) producing the report through a contextual analysis based on one’s insights. In step 1, one researcher listened to and transcribed all the taped interviews, which resulted in 618 single-spaced pages of content. Three of the researchers’ first-read of the entire data set took 37+ hours each, whereby notes were taken while reflexively immersing in the data. Researchers then re-read their notes subsequently with the intent of critical engagement with the data. Coding during stage 2 included entering semantic as well as latent code labels throughout each researcher’s version of the dataset. During this stage, the researchers moved between electronic copies and Microsoft Excel versions of the data. In stage 3, broad candidate themes were first identified based on the cluster of codes. These themes were associated with the focus on this study, which was to examine the medical histories of formerly sex trafficked women and their healthcare experiences while they were trafficked. During the “develop and review theme” phase in stage 4, the themes went through several iterations after three coders read and re-read the data in detail. This included analyzing the entire constellation of data. This resulted in deleting or collapsing themes until three of the researchers felt the candidate themes best reflected the shared meaning of the respondents in the study, as illustrated in rich, thick extracts by respondents. In other words, the researchers felt the information power of the data had reached its peak. In stage 5, a synopsis of the four candidate themes was written to capture their meaning. Last, stage 6 is reflected in the reporting of the findings.

Results

Sample

Fifty (n = 50) sex trafficking survivors participated in this study. All participants identified as cisgender women, with one participant identifying as a transgender woman. Nearly 70% (n=34) of the respondents identified as White, while 26% (n=13) identified as being Black/African American. The remaining 6% (n=3) identified as multiracial or Native American. The mean age of participants was 42.6 (SD = 11.6), with a range of 24 to 70 years of age. Of note, nearly half (46%; n = 23) were under the age of 18 years old at the time of entry into sex trafficking. The median age of the participants’ exit from sex trafficking was 32.5 years old. The duration of trafficking among participants varied widely, from 6 months to 32 years. Many participants (43.2%; n=19) sought healthcare at least once per year. An equal number of participants (43.2%; n=19) sought healthcare at least once every 5 years. A minority of participants (6.8%; n=3) sought healthcare once every 10 years, and one participant waited longer than 10 years to seek healthcare. See Table 1 for additional sociodemographic characteristics.

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics (N=50)

| Characteristics | n | % |

| Race/Ethnicity

White Black/African American Other (Native American or multiracial) |

34 13 3 |

68 26 6 |

| Length of Trafficking

6 months-4 years 5-9 years 10-19 years 20+ years |

17 6 14 13 |

34 12 28 26 |

| Age First Trafficked (x=12; SD = 9.1)

5-9 10-17 18-24 25-35 35+ |

3 20 15 10 2 |

6 40 30 20 4 |

| Current Age (x=42.6; SD = 11.6)

20-29 30-39 40-49 50-60 60+ |

8 15 13 9 5 |

16 30 26 18 10 |

| Sexual Orientation

Gay or Lesbian Bisexual Heterosexual Other |

2 10 36 2 |

4 20 72 4 |

| Marital Status

Divorced Married Separated Single/Never Married Widowed |

13 9 4 21 3 |

26 18 8 42 6 |

| Employment Status

Parttime Fulltime Other |

7 20 23 |

14 40 46 |

| Income

<$10,000 $10,000-$20,000 $20,001-$30,000 $30,001-$40,000 $40,001-$50,000 $50,001+ Missing |

3 7 10 1 5 2 22 |

6 14 20 2 10 4 44 |

| Education

Some High School High School Diploma/GED Vocational Training Some College College Degree (undergrad) Master’s |

13 13 1 20 2 1 |

26 26 2 40 4 2 |

| Healthcare Seeking Habits

1x a year Once every 5 years Once every 10 years Over 10 years |

19 19 3 1 |

43.2 43.2 6.8 2.3 |

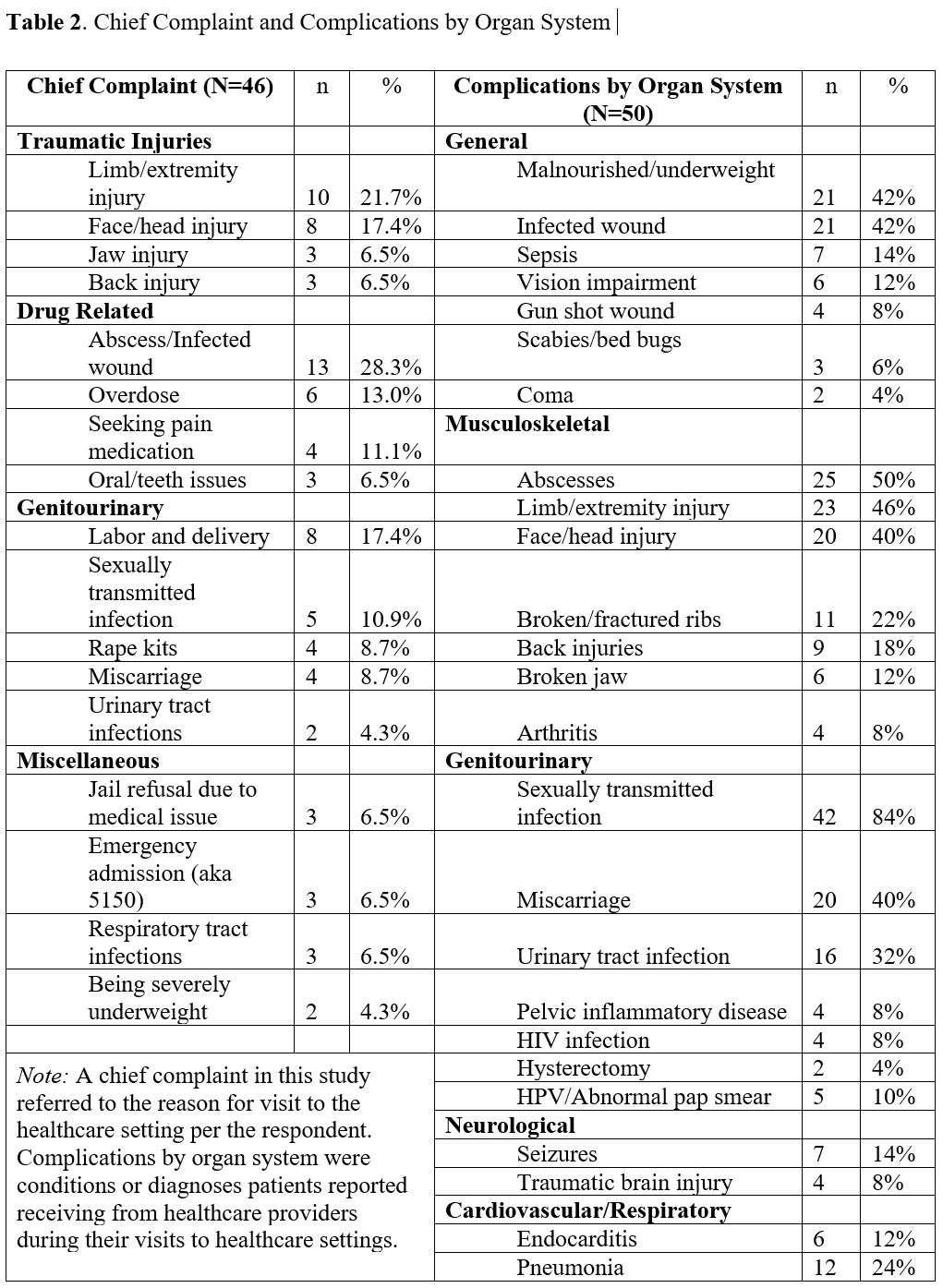

In this study, a variety of chief complaints and complications by organ system were identified as listed in Table 2. Related to the healthcare experiences of formerly trafficked women, three themes resulted after an extensive reflexive coding process. They include A) drug use, B) judgment by healthcare providers, and C) lack of identification by healthcare providers. (See Table 3 for a description of the themes.)

Chief Complaints and Complications by Organ System

Participants reported a variety of chief complaints. As shown in Table 2, the most common chief complaints were related to traumatic injuries. Many of the participants reported seeking out healthcare for injuries they sustained at the hands of their trafficker or a buyer. The location of injuries varied, and gravity of each injury ranged from minor to severe. Limb/extremity injuries were the most common location, and some examples included broken bones, lacerations requiring stitches, and burns. Face/head injuries were the next most common and some examples included orbital fracture, broken jaw, and lacerations to the face, lip, and scalp requiring stitches. Tanya, for instance, described having been knocked unconscious on several occasions by various perpetrators. She reports, “I think I might’ve had five, seven stitches in my head” after a violent assault. Prior to this assault, Tanya also reported being “busted” in the head and suffering from a “broken jaw.” Jaw injuries were reported among a few of the respondents as a chief complaint. While back injuries, which included spinal or vertebral injuries were less frequent than many other injuries, back injuries were also some of the most severe and life-threatening. Leticia described how she sustained her back injury:

“He opened the window, and he threw me out. And I landed on my feet, and it just snapped my spine and like exploded three vertebrae and it like shot all through … I was bleeding internally. My spine was snapped in half. I was paralyzed. I could not move from the waist down, so I was crawling through the grass in the back of the hotel like on my elbows and screaming for help.”

Following traumatic injuries, the second most common chief complaint was abscesses/infected wounds. Abscesses and infected wounds were primarily related to intravenous drug use. Many participants reported having abscesses at some point while they were trafficked, but only roughly half of these participants received healthcare for their abscesses. Julia described her experience with abscesses:

“I’ve had several abscesses…like I had one…that I did have to go to the hospital for it and have it cut open because it was like on my left side like right above my collarbone because I was shooting into my neck at one point—I couldn’t find a vein anywhere else…I’ve had abscesses on my arms that I cut open myself with box cutters, I think, to get the infection out because I didn’t want to go to the hospital.”

Other participants reported cutting open their abscesses themselves with box cutters too or with razor blades. Still others like Ivy relied on home remedies that would “pop” the abscess and make “this stuff just come gushing out.”

Participants were also surveyed about health complications that incurred while being trafficked. These results are organized by organ system as shown in Table 3. The most reported health complications were sexually transmitted infections (STI), abscesses, limb/extremity injuries, malnourishment, infected wounds, face/head injuries, and miscarriages. The most common gynecologic healthcare access point was labor and delivery. Most participants reported giving birth at least once in their lifetime, but many chose to give birth where they were living at the time. Similarly, most participants reported contracting an STI while being trafficked, but few reported STIs as their chief complaint when receiving healthcare. Oftentimes, participants sought out healthcare for other reasons, and an STI was incidentally found in their workup. The more severe health complications participants reported were sepsis, endocarditis, and gunshot wounds. For instance, Lissette described a gunshot wound to the foot. “They didn’t do sh#t! They cleaned it, wrapped it and that’s it. The bullet went through everything so there wasn’t much that they could do.” She was admitted to the hospital that day, however, but for a more serious medical condition. Last, all participants endorsed being diagnosed with a mental disorder at some point after being trafficked, while a few reported being taken to the Emergency Department (ED) for psychiatric related issues via an involuntary hold or a 5150.

When asked to describe their health care experiences as sex trafficked women, respondents’ remarks clustered around three themes that include drug use, judgment by healthcare providers, and the lack of identification by healthcare providers. (See Table 3 for descriptions of each theme.)

Table 3. Themes

| Themes | Characteristics |

| Drug Use | This theme relates to illicit substance use by the sex trafficked woman and its impact on her body and life. |

| Judgment by Healthcare Providers | Judgment was expressed in the context of a provider appearing to critique and condemn the respondent on moral grounds related to her drug use and/or participation in the sex trade. |

| Lack of Identification by Healthcare Providers | This theme encompassed the missing red flags (e.g., symptoms, behaviors, mannerisms, etc.) that survivors presented with during healthcare visits. |

Drug Use

Drug use in this theme relates to illicit drug use and its effect on the sex trafficked woman. All but one respondent in this study used illicit drugs while being trafficked. Crack was the most commonly used drug among the participants. Other common illicit drugs reported include marijuana, heroin, cocaine, and meth. Many participants stated that drug use and trafficking frequently co-exist. As Shannon explained:

So even if a woman is introduced into the lifestyle and she doesn’t have a drug addiction, I find it very rare in my experience and from what I’ve seen that they don’t turn to it, eventually. So, it kind of goes hand in hand. And then especially at a street level, most women are already using and are introduced into the lifestyle.

Leah reports early drug use as drinking alcohol at age 15, smoking marijuana at age 17, and then moving on to pills, crack, heroin, and meth later. She reports, “I’ve never done LSD, but I’ve done like K2 acid. I’ve done ecstasy. And then I’ve drank that codeine drink or whatever blue drink.” Polysubstance use was common in this sample population. In a life-threatening case of chronic drug use, Ivy reported, “I weighed, say 71 pounds…I had the flu, pneumonia, HIV, MRSA, Hep C; I had abscesses in my stomach…I was so on drugs… I hadn’t showered probably in a month and a half.” In this case, Ivy almost died and was forced into care by family members.

Judgment by Healthcare Providers

While it was common for women in this study to seek a healthcare provider while being sex trafficked, participants endorsed many barriers to accessing healthcare during their sex trafficking victimization due to a complex interplay between factors. For instance, the most common reason participants avoided accessing healthcare was due to judgment on moral grounds—especially when drug use was a contributor to the health complaint. As an illustration, Lauren shared she felt like she was treated “…like I’m just a worthless drug addict, which is often the case if I were to go to the emergency room or something and come across a doctor that’s not educated in addiction. They’re often very judgmental.” As a result of this, many participants reported leaving against medical advice because they felt judged. Constance explains, “There were a lot of different people who were just like… you brought this on yourself. I’m not going to do anything to make you comfortable, you’re a drug addict”. Penelope agreed and shared that she felt judged based on perceived identities as “a drug addict, a prostitute, [and] scum of the world.” Reportedly, she felt shame and embarrassment and did not feel comfortable disclosing that she was under the control of a trafficker whom she referred to as her “God.” Women in this study reported experiencing a form of judgment or bias where they were made to feel as though they were at fault or had overstepped by seeking treatment for their injuries or illnesses. This perception implies that their seeking of help was somehow inappropriate or unjustified, possibly due to assumptions that they were somehow complicit in their own suffering.

Lack of Identification by Healthcare Providers

Most participants (89.1%) received healthcare in the Emergency Department (ED). Only 26.2%, however, reported being identified as a trafficked patient by a healthcare provider. Being identified meant that patients were either directly asked if they were sex trafficked or were offered resources for sex trafficked persons. Almost all participants believed there were red flags that indicated sex trafficking (e.g., physical exam findings), however. Examples include repeated STIs, signs of drug use (e.g., intoxication, withdrawal, +drug screen, abscesses), signs of homelessness (e.g., extremely poor hygiene), malnutrition, signs of physical abuse (e.g., bruises, broken bones, lacerations), and atypical behavior (e.g., lack of eye contact, refusing treatment, avoiding answering questions). Noelle reported that it was obvious that she was lying to doctors during a visit, but no one challenged her story, “I assumed that because these doctors were professional…They’re experts, they know what a knife wound looks like… I said I fell on a fence.” Anna reported other signs that she felt providers should have flagged, “Bruises, um poor hygiene, burn marks. I mean burn marks alone…I guess there are people who burn themselves but like there was no eye contact.” Given the constellation of symptoms and behaviors, many participants felt that healthcare providers should have picked up on their precarious situations especially when they presented as fidgety or skittish or not wanting to be touched. In a few situations, participants reported that their trafficker was with them during the healthcare encounter, and no one took note of their companion.

Discussion

Based on the findings of this study, it is crucial for society to undergo a paradigm shift in how we address chief complaints and complications resulting from interpersonal violence in healthcare settings, particularly in cases involving victims of sex trafficking. Sex trafficking is not only a severe form of interpersonal violence, encompassing physical, sexual, and psychological abuse, but it also imposes significant emotional and physical exhaustion on its victims. The phenomenon of sex trafficking is complex and nuanced, often accompanied by a range of seemingly unrelated adverse events and circumstances that contribute to its misunderstanding—especially the role of illicit drug use.

Sex trafficking, by definition, involves force, fraud, or coercion (Pub. L. No. 106-386). Empirical evidence highlights its associations with a variety of severe outcomes, including traumatic injuries, psychological disorders, gastrointestinal issues, drug misuse, cardiovascular conditions, neurological problems, and genitourinary issues (Ertl et al., 2020; Menaker & Franklin, 2015; Meshelemiah et al., 2023; Lederer et al., 2023; Saunders & Harris, 2019; Zimmerman et al., 2011). In this study, respondents reported 1) a range of chief complaints and complications by organ system, 2) pervasive drug use, 3) feelings of being judged when seeking healthcare, and 4) lack of identification by healthcare providers. These issues and challenges are consistent with the plight of those who have been relegated to the periphery and denied equitable access to healthcare.

Judging sex-trafficked women who seek healthcare reflects a passive and reactive approach to modern medical practice. It is inadequate to attribute their diverse symptoms and complications solely to self-abuse or their involvement in the sex trade. Instead, it is crucial to delve deeper and develop a more compassionate and comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay of factors contributing to their health issues and vulnerability to extreme forms of interpersonal violence. The social determinants of health framework is a public health approach that captures the complexities and systemic factors contributing to the challenges faced by trafficked women. In this study, 32% of the women were racialized, and over 70% of those who reported their incomes earned less than $30,001 annually. Additionally, 52% had education levels at or below the high school diploma. These sociodemographic factors further marginalize their experiences and identities, compounding their vulnerability. A shift toward a more nuanced understanding of sex-trafficked women, their sociodemographic backgrounds, and the full range of their health concerns will enhance the quality of care and support provided to this marginalized and vulnerable population.

Sex Trafficking and Healthcare

The findings of this study highlight that sex-trafficked patients endure severe interpersonal violence and often seek healthcare, particularly in emergency departments, consequently (Schwarz et al., 2016; Shekhar & Macias-Konstantopoulos, 2023). Lederer and Wetzel (2014) interviewed 107 sex trafficking victims and survivors in 12 focus groups across several cities in the U.S. They also surveyed them using a comprehensive tool on violence victimization, healthcare experiences, and symptoms post-trafficking. These researchers found, post trafficking, that 99.1% reported at least one physical health problem, and 96.4% reported at least one psychological issue. During the trafficking ordeal, 84.3% reported forced drug use or drug use because of traumatic circumstances. In a follow-up study in 2023, Lederer et al. (2023) found that 90% (n = 28) of trafficking survivors had at least one gynecological issue and that 81% sought healthcare in hospitals or emergency rooms. Additionally, only 12.9% agreed that medical professionals delivered care with excellence and only 9.7% agreed that medical professionals were trauma-informed.

While sex trafficked patients frequently have gynecologic and reproductive health complications (Lederer et al., 2023; Shandro et al., 2016), these are not typically the health issues that bring them to healthcare settings but rather are incidental findings when seeking care for other conditions. For instance, women in our study reported widespread traumatic injuries, mental health challenges, and illicit drug use too—further supporting research that asserts that sex trafficking is very complicated and results in a myriad of consequences for the victim/survivor (Lederer et al., 2023; Macias-Konstantopoulos, 2016; Zimmerman et al., 2011). Integrative services or interagency coordination of services are critical for this population due to the duplicity of their victimization. Researchers from a 9-site SAMHSA funded study on co-occurring disorders and violence recommend trauma-informed alcohol and other drugs (AOD) and mental health services to women with violent experiences in their backgrounds (Markhoff et al., 2005). This recommendation is important for sex trafficked women because the approach may minimize re-traumatization and may help to break down barriers between the victim and healthcare provider. For instance, drug use was widespread among women in the current study and many times served as a source of judgment, and even health complications. Some survivors even reported lacking transparency with healthcare providers about the source of their injuries or conditions because of it. If the emergency healthcare provider better understood trauma and drug use, the healthcare environment may be more conducive to building rapport and making immediate referrals to team members to address complex biopsychosocial needs, especially when sex trafficking is involved.

According to the precision medicine philosophy of “target the right treatments to the right patients at the right time” (U.S. FDA, 2018, para 1), one-size-fits-all medical approaches is not ideal. This is especially true for sex trafficked women. Personalized medicine that evokes prioritized integrative care would allow the healthcare provider and team members to address traumatic injuries, physical health, mental health challenges, and illicit drug use in safe spaces. It is critical to note that among sex trafficked women, barriers to healthcare utilization are situated in the victim’s lived experiences of pervasive and often long-term loss of agency due to extreme victimization, trauma coerced attachment to the trafficker (Doychak & Raghaven, 2020), as well as the pharmacodynamics of their addiction (McCoy et al., 2001). Such factors impact the patient’s behavioral and physical presentation, willingness to receive treatment, and compliance with medical providers. Knowledge of the victim’s perception, which is altered through their survival-based attachment to their trafficker and illicit drugs, is critical to addressing the complex physical and mental health needs of this population (Meshelemiah et al., 2018). Sequential or separate care for these issues is a lost opportunity to better serve victimized women.

Breaking Down Barriers: Implications for Practice and Policy

Healthcare settings have unique challenges when serving sex trafficked women (Elliott et al., 2005). To overcome these challenges, recommendations include 1) implementing practice and policy protocols around increased education and training on sex trafficking, and 2) utilizing multidisciplinary teams. Specifically, implementing protocol that requires education and training on sex trafficking for healthcare providers during one’s formal training and throughout one’s professional practice is recommended (Chang et al., 2022). Shekhar and Macias-Konstantopoulos (2023) report that when providers receive human trafficking education, they are better equipped to recognize, care for, and interact with trafficked persons. For instance, receiving training on a sex trafficking screening tool is a good first step in the identification process (Eickhoff et al., 2022; Mumma et al., 2017; Unertl et al., 2021) and sets the stage for good practice. Two trafficking questionnaires that have been validated for use in healthcare setting include one for minors (see Greenbaum et al., 2018) and one for adults in the Emergency Department (see Chisolm-Straker et al., 2021). Providers must also become educated on the intersection of drug use, psychological disorders, health challenges, and sex trafficking violence in an effort to avoid diagnostic overshadowing. Diagnostic overshadowing is “a well-described clinically and ethically problematic phenomenon in which clinicians ignore patients’ general health concerns because of that patient’s mental illness” (Stoklosa et al., 2017, p. 29). In this study, some health concerns were ignored and judged due to their drug use (classified as a psychological disorder in the DSM-5-TR) and involvement in the sex trade. Stoklosa et al. (2017) assert that these types of biases result in clinical errors and unmet healthcare needs.

Trained multidisciplinary teams or “flash teams” that come together as needed (Murphy et al., 2019, p.1) are also important when providing healthcare services to trafficked persons because of the complexity, and sometimes life-threatening needs of these individuals (Jain et al., 2022; Jones & Mitchell, 2022; Shandro et al., 2016). Multidisciplinary teams (MTDs) composed of diverse members (e.g., receptionist, social worker, nurse, physician, peer support, chaplain, radiology technician, care coordinator (aka case manager), law enforcement officer, etc.) may result in increased sensitivity and improved efficiency for a patient (Jones & Mitchell, 2022; Long et al., 2015; Macias-Konstantopoulos, 2016; Markhoff et al., 2005; Saunders, 2015; Shandro et al., 2016; Subramaniyan et al., 2017; Vaughn, 2023). Jones and Mitchell’s (2022) study with 171 professionals indicated that multidisciplinary teams’ work with child sex trafficking cases was met with greater success when team members were properly trained on trafficking indicators. Levine (2017) advocates for healthcare organizations to establish protocols for both short- and long-term interventions through a multidisciplinary approach. This approach should address the full spectrum of needs associated with sex trafficking, including psychological trauma, physical injuries, drug addiction, and safety concerns arising from the extreme nature of the exploitation. Effective intervention requires collaboration among various professionals: psychiatrists to manage psychological trauma, social workers to address social and environmental issues, law enforcement officers to handle legal matters, and healthcare providers to treat physical health concerns. No single discipline can comprehensively address the multifaceted needs of sex-trafficked women due to the profound and varied impacts of their experiences.

Limitations

Snowball sampling was effective in reaching potential respondents for this study. This form of recruitment, however, self-selects for respondents who know each other and may have similar experiences, potentially leading to similar responses. The respondents in this study were also predominately White. A more racially diverse group of respondents may yield specific experiences related to racialization that were not explored in this study. Additionally, this is a retrospective study, and this may have affected participants’ recollection depending on how long ago it was since last trafficked. Last, this study focused on the healthcare experiences of women during the trafficking ordeal. Given the wide range of trafficking durations and the diverse frequencies in which women sought out healthcare, it is quite possible that healthcare interactions with providers are much improved in non-emergency room settings or when the sex trafficked woman is an established patient in a practice. These elements should be explored in a future study.

Conclusion

Women seek healthcare services while being sex trafficked. Providers have the responsibility to detect and address the complexity of their conditions, which requires competence, sensitivity, and knowing what to do and where to go to for assistance. Formal education and training are important. A shift in protocol in healthcare settings would require healthcare providers to have the capacity to properly identify sex trafficked women who present with varied presentations and atypical chief complaints. This includes acquiring an in-depth understanding of what sex trafficking is and its relationship with interpersonal violence, drug use and multilayered health (physical and mental) consequences. Last, the use of multidisciplinary teams is a critical first step to better serving sex trafficked women due to the complexity of the violence associated with sex trafficking.

References

Ades, V., Wu, S.X., Rabinowitz, E., Chemouni, S., Goddard, B., Ayala, S.P., & Greene, J. (2019). An integrated, trauma-informed care model for female survivors of sexual violence: The engage, motivate, protect, organize, self-worth, educate, respect (EMPOWER) clinic. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 133(4), 803-809. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003186 Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage. Chang, K.S.G., Tsang, S., & Chisolm-Straker, M. (2022). Child trafficking and exploitation: Historical roots, preventive policies, and the pediatrician’s role. Current Problems in Pediatric Adolescent Health Care, 52(3), 1-20. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2022.101167.

Chisolm-Straker, M., Singer, E., Strong, D., Loo, G.T., Rothman, E.M., Clesca, C., d’Etienne, J., Alanis, N., & Richardson, L.D. (2021). Validation of a screening tool for labor and sex trafficking among emergency department patients. Journal of American College Emergency Physicians Open, 2(5), e12558, doi: 10.1002/emp2.1255

Dane, F.C. (2011). Evaluating research: Methodology for peope who need to read research. Sage Publications.

Doychak, K. & Raghavan, C. (2020). “No voice or vote”: Trauma-coerced attachment in victims of sex trafficking. Journal of Human Trafficking, 6(3), 339-357. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2018.1518625

Eickhoff, L., Kelly, J., Simmie, H., Crabo, E.M., Baptiste, D., Maliszewski, B, A., & Goldstein, N. (2022). Slipping through the cracks-detection of sex trafficking in the adult emergency department: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 32, 5948-5958. doi: 10.1111/jocn.16727

Elliott, D.E., Bjelajac, P., Fallor, R.D., Markoff, L.S., & Reed, B.G. (2005). Trauma-informed or trauma-denied: Principles and implementation of trauma-informed services for women. Journal of Community Psychology, 33(4), 461-477. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20063

Ertl, S., Bokor, B., Tuchman, L., Miller, E., Kappel, R., & Deye, K. (2020). Healthcare needs and utilization patterns of sex-trafficked youth: Missed opportunities at a children’s hospital. Child Care, Health and Development, 46(4), 422-428.

https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12759

Greenbaum, V.J., Dodd, M., & McCracken, C. (2018). A short screening tool to identify victims of child sex trafficking in the health care setting. Pediatric Emergency Care, 34(1),33-37. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000602

Jain, J., Bennett, M., Bailey, M., Liaou, D., Kaltiso, S.O., Greenbaum, J., Williams, K., Gordon, M.R., Torres, M.I.M., Nguyen, P.T., Coverdale, J.H., Williams, V., Hari, C., Rodriguez, S., Salami, T., & Potter, J.E. (2022). Creating a collaborative trauma-informed interdisciplinary citywide victim services model focused on health care for survivors of human trafficking. Public Health Reports, 137(Supplement 1), 30S-37S.

Jones, L.M., & Mitchell, K.J. (2022). Predictors of multidisciplinary team sustainability in work with child sex trafficking cases. Violence and Victims, 37(2), 222-243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/VV-D-19-00073

Karandikar, S., Dalla, R.L., & Casassa, K. (2024). The Women and children of India’s red-light brothel districts: An exploratory investigation of vulnerability and survival during a global pandemic. Community Health Equity Research & Policy, 0(0), 1-15. DOI: 10.1177/2752535X241280226

Krysik, J.L., & Finn, J. (2013). Research for effective social work practice (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Lederer, L.J., Flores, T., & Chandler, M.J. (2023). The pregnancy continuum in domestic sex trafficking in the United States: Examining the unspoken gynecological, reproductive, and procreative issues of victims and survivors. Issues in Law and Medicine, 38(1), 61-76. PMID: 37642454

Lederer, L.J., & Wetzel, C.A. (2014). The health consequences of sex trafficking and their implications for identifying victims in healthcare facilities. Annals of Health Law, 23, 61-91.

Levine, J.A. (2017). Mental health issues in survivors of sex trafficking. Cogent Medicine, 4. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205X.2017.1278841

Long, A.M., Mowery, N.T., Chang, M.C., Johnson, J.E., Miller, P.R., Meredith, W., & Carter, J.E. (2015). Golden opportunity: Multidisciplinary stimulation training improves trauma team efficiency. Scientific Forum Abstracts, 221(4S1), S57.

Macias-Konstantopoulos, W., Ahn, R., Alpert, E.J., Cafferty, E., McGahan, E., Williams, T.P., Castor, J.P., Wolferstan, N., Purcell, G., & Burke, T.F. (2013). An international comparative public health analysis of sex trafficking of women and girls in eight cities: Achieving a more effective health sector responses. Journal of Urban Health, 90(6), 1194-1204. doi:10.1007/s11524-013-9837-4

Macias-Konstantopoulos, W.L. (2016). Human trafficking: The role of medicine in interrupting the cycle of abuse and violence. Annals of Internal Medicine, 165(8), 582-588. doi:10.7326/M16-0094

Markoff, L.S., Reed, B.G., Fallot, R.D., Elliott, D.E., & Bjelajac, P. (2005). Implementing trauma-informed alcohol and other drug and mental health services for women: Lessons learned in a multisite demonstration project. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75(4), 525-539. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.4.525

McCoy, C.B., Metsch, L.R., Chitwood, D.D., and Miles, C. (2001). Drug use and barriers to health care services. Substance Use and Misuse, 36(6 & 7), 789-806. https://doi-org/10.1081/JA-100104091

Menaker, T., & Franklin, C. (2015). The diverse needs of sex trafficking survivors. Human Trafficking Series, 2(3), 1-3.

Meshelemiah, J.C.A., Gilson, C., & Prasanga, A.P.A. (2018). Use of drug dependency to entrap and control victims of sex trafficking: A call for a U.S. federal human rights response. Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence, 3(3), Article 8, 1-4. doi: 10.23860/dignity.2018.03.03.08

Meshelemiah, J.C.A., Thanises, A.C., & Yeboah, P.O. (2023). Sex trafficked women, drug dealers, and men who buy sex: A look at “Race”. Violence Against Women, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012231216711

Mumma, B.E., Scofield, M.E., Mendoza, L.P., Toofan, Y., Youngyunpipatkul, J., & Hernandez, B. (2017). Screening for victims of sex trafficking in the emergency department: A pilot program. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 18(4), 616-620. doi:10.5811/westjem.2017.2.31924

Murphy, M., McCloughen, A., & Curtis, K. (2019). Using theories of behavior change to transition multidisciplinary trauma team training from the training environment to clinical practice. Implementation Science, 14(43), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0890-6

Pub. L. No. 106-386 [Trafficking Victims Protect Act of 2000]

Rajaram, S.S., & Tidball, S. (2018). Survivor’s Voices—Complex needs of sex trafficking survivors in the Midwest. Behavioral Medicine, 44(3), 189-198. doi:10.1080/08964289.2017.1399101

Ricci, S.S. (2017). Violence against women: A global perspective. Women’s Health Open Journal, 3(1), e1-e2. http://dx.doi.org/10.17140/WHOJ-3-e007

Robichaux, K., & Torres, M.I.M. (2022). The role of social determinants in caring for trafficked patients: A public health perspective on human trafficking. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 86(Supplement A). https://doi.org/10.1521/bumc.2022.86.suppA.8

Saunders, C.B. (2015). Preventing secondary complications in trauma patients with implementation of a multidisciplinary mobilization team. Journal of Trauma Nursing, 22(3), 170-175. doi: 10.1097/JTN.0000000000000127

Saunders, P.J. & Harris, M. (2019). Poor understanding of modern slavery in the healthcare system. British Medical Journal, 365, 1449. doi: 10.1136/bmj

Schwarz, C., Unruh, E., Cronin, K., Evans-Simpson, S., Britton, H., & Ramaswamy, M. (2016). Human trafficking identification and service provision in the medical and social service sectors. Health and Human Rights Journal, 18(1), 181-191.

Shandro, J., Chisolm-Straker, M., Duber, H.C., Findlay, S.L., Munoz, J., Schmitz, G., Stanzer, M., Stoklosa, H., Wiener, D.E., & Wingkun, N. (2016). Human trafficking: A guide to identification and approach for the emergency physician. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 68(4), 501-508. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.03.049

Shekhar, A.C., & Macias-Konstantopoulos, W.L. (2023). Human trafficking and emergency medical services (EMS). Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 38(4), 541-543. doi:10.1017/S1049023X23005976

Stoklosa, H., MacGibbon, M., & Stoklosa, J. (2017). Human trafficking, mental illness, and addiction: Avoiding diagnostic overshadowing. AMA Journal of Ethics, 19(1), 23-34. 10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.01.ecas3-1701

Subramaniyan, V.K.S., Mital, A., Rao, C., & Chandra, G. (2017). Barriers and challenges in seeking psychiatric intervention in a general hospital, by the collaborative child response unit (a multidisciplinary team approach to handling child abuse): A qualitative analysis. Indian Psychiatric Society, 39(1), 12-20. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.198957

Unertl, K.M., Walsh, C.G., & Clayton, E.W. (2021). Combat human trafficking in the United States: How can medical informatics help? Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 28(2), 384-388. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa142

U.S. Food & Drug Administration [FDA]. (2018). Precision medicine. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/in-vitro-diagnostics/precision-medicine#:~:text=The%20goal%20of%20precision%20medicine,patients%20at%20the%20right%20time

Vaughn, J. (2023). Evidence-based pearls: How the healthy work environment effects multidisciplinary trauma teams. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America, 35, 101-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnc.2023.02.002

Vo, T., Scholar, J., & Purkayastha, B. (2023). Global health care experiences of female survivors who experienced trafficking: A meta-ethnography. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 68(2), 221-232. doi:10.1111/jmwh.13449

Walker, E.D., & Reid, J.A. (2024). On the overlap of commercial sexual exploitation and intimate partner violence: An exploratory exploitation of trauma-related shame. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 39(15-16), 3669-3686. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605241233268

World Health Organization [WHO] (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health: Debates, policy, & practice, case studies. Author.

World Health Organization. (2024). The VPA approach. https://www.who.int/groups/violence-prevention-alliance/approach

Zimmerman, C., Hossain, M., & Watts, C. (2011). Human trafficking and health: A conceptual model to inform policy, intervention and research. Social Science & Medicine, 73, 327-335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.028

Co-authorship

[1] Co-first author; The Ohio State University, College of Social Work, 325D Stillman Hall, 1947 North College Road, Columbus, Ohio 43210; email: meshelemiah.1@osu.edu; ORCID: 0000-0001-9840-9258

[2] Co-first author; University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Emergency Medicine Resident, San Francisco, San Francisco, California; email: khalsa.skk@gmail.com

[3] The Ohio State University, College of Social Work, 1947 North College Road, Columbus, Ohio 43210, email; steinke.86@buckeyemail.osu.edu, ORCID: 0009-0000-5596-0701

[4] The Ohio State University, College of Social Work, 325Y Stillman Hall, 1947 North College Road, Columbus, Ohio 43210; email: karandikar.7@osu.edu

[5] The Ohio State University, College of Social Work, 325E Stillman Hall, 1947 North College Road, Columbus, Ohio 43210; email: hu.2915@osu.edu