Chapter 7: Child Brides and Mail Order Brides

Abstract

Arranged marriages are usually a cultural practice in which families will choose spouses for their children. Often, arranged marriages are not sinister in nature. Child marriages, however, are viewed by many as sinister in nature and a detriment to the child. Child marriage is a form of an arranged marriage whereby one or both of the individuals are less than 18 years of age. In the case of many girls, child marriages put young girls at risk for domestic abuse, pregnancy/child birth complications, and HIV. Mail-order brides are also a form of arranged marriage where a spouse is purchased through the internet with the aid of a marriage broker, generally by a person with means to do so or a wealthy person in general. Some of these arranged marriages result in forms of human trafficking and violate the rights of women and children who are a part of them. This chapter will explore the injustices and exploitation within these forms of matrimony.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Define child bride and child marriage

- Define mail order bride

- Understand how child brides and mail order brides may be viewed as human trafficking in some instances

- Identify efforts to prevent or stop arranged marriage practices that fall under human trafficking

Key Words: Child Bride, Child Marriage, Arranged Marriage

GLOSSARY

Child Bride: A child under the age of 18 who is married, or is to be married, to an older person (usually a man); generally child brides’ marriages are arranged by their parents for the girls’ financial safety or to take the financial burden off the family

Child Marriage: Any marriage where at least one of the people to be married is under the age of 18

Arranged Marriage: A marriage in which the family, usually parents, of each of the spouses decide and agree upon the marriage

Mail Order Bride: A woman ordered over the internet through a broker for a fee to be married to a man in a foreign country

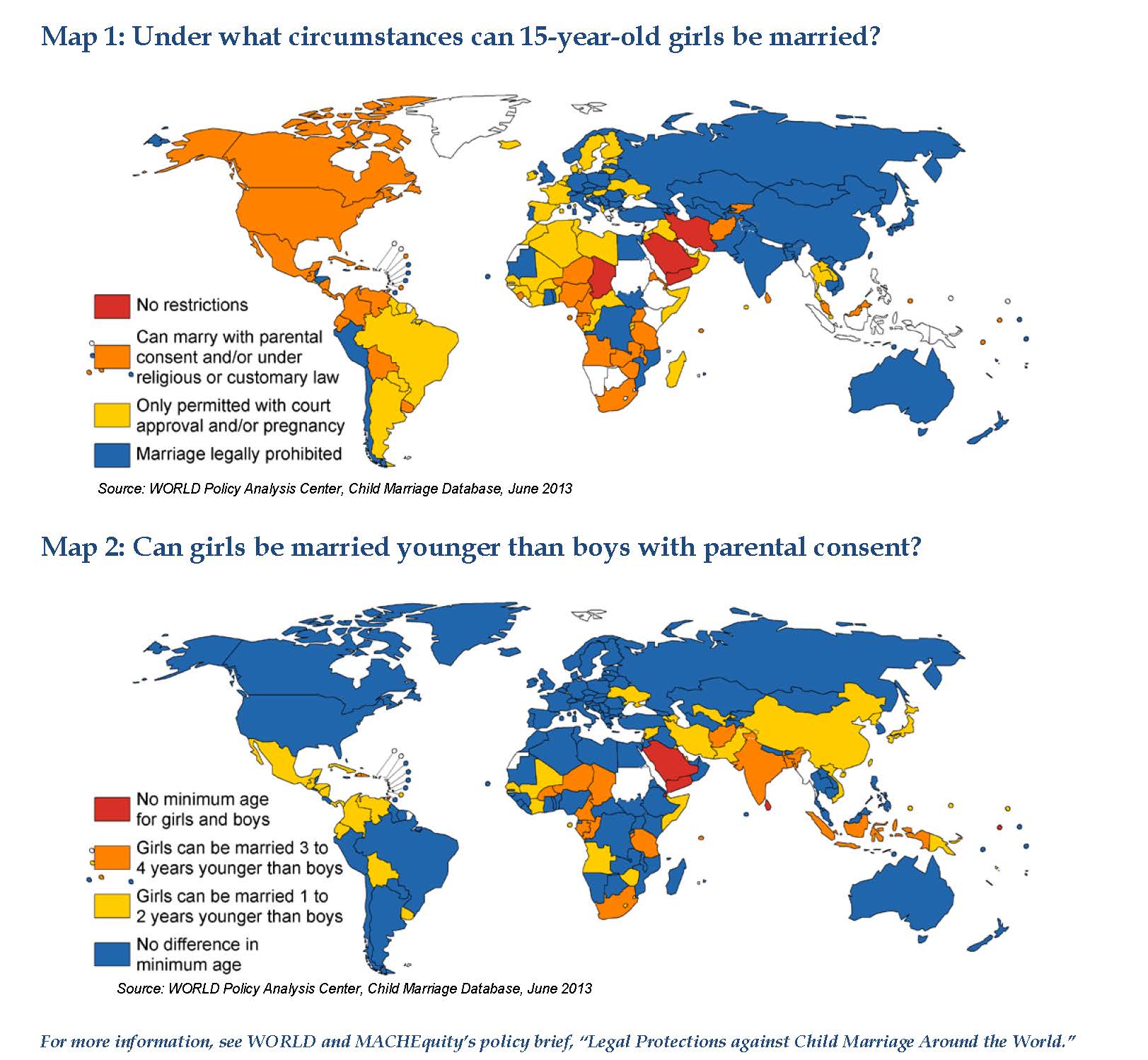

Child marriages most often involve girls and include matrimonies that take place before the girl turns 18. In general, a child marriage is a marriage in which one or both of the people to be married are under the age of 18. Some child marriages are formally arranged by family members within a cultural context, and others may be more informal (Chakraborty, 2019; Selby & Singer, 2018; United Nations, 2013). Most often, child brides are girls who marry much older men. Many brides are under the age of 15 (Selby & Singer, 2018; United Nations, 2013). The practices of child brides and child marriages are a global issue, with an estimated 12-18 million girls being married before the age of 18 every year (Girls Not Brides, 2019; Selby & Singer, 2018; United Nations, 2013). One of the reasons why child brides are so prevalent is because, despite 88% of countries worldwide having laws that forbid marriage before the age of 18, exceptions can be made if the parents of the child consent to the marriage (World Policy Analysis Center, 2015). Twenty-seven percent of the countries that do have laws that require parental consent also have legal loopholes where parents can consent for girls two to four years earlier than for boys (World Policy Analysis Center, 2015). See Figure A. Maps 1 and 2 that illustrates the number of countries with lax laws about 15 year old’s getting married and boys vs girls getting married.)

Figure A. Maps 1 & 2

Source: https://www.worldpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/WORLD_Fact_Sheet_Legal_Protection_Against_Child_Marriage_2015.pdf

Marrying children is a worldwide problem crossing cultural, regional, and religious lines. Though it is more common in developing countries in the Southeast region of Asia and Africa, it still happens in developed countries like the United States (Selby & Singer, 2018; United Nations, 2013; United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), 2018). Globally, 21% of girls are married off before the age of 18, which is tens of thousands of girls every single day, and that number doubles to 40% in developing countries with 12% of those girls being under the age of 15 (UNICEF, 2018; United Nations Population Fund, 2018). Areas with high poverty levels and lax (if any) laws surrounding child marriage typically produce more child brides, along with areas where young girls marrying older men is a cultural norm (International Center for Research on Women (ICRW), n.d.; Selby & Singer, 2018; United Nations, 2013). Due to gender inequality in many regions of the world, girls are not always considered wage-earners, but instead a drain on family funds. Therefore, especially in regions with unstable political climates and where war and conflict are prominent, families will marry off their daughters to ensure that she is taken care of financially by her husband instead of them (Selby & Singer, 2018; United Nations Population Fund, 2018). Again, despite being more common in developing countries, child brides are prevalent in the developed world as well. In the United States, over 200,000 children were married between 2000 and 2015, with 86% of them being married to adults (Tahirih Justice Center, 2017). In many cases, the girl to be married was pregnant, the soon-to-be husband was decades older, and the girl was marrying her rapist in a case of statutory rape (Tahirih Justice Center, 2017). If current worldwide trends continue uninterrupted, more than 140 million girls will become child brides in the next decade alone (International Women’s Health Coalition, n.d.).

Reasons for Child Marriages

The context for child marriage varies across cultures and regions. In poverty and war-stricken countries, parents may marry off their children for her financial security or protection, or because they cannot afford to care for her (Chakraborty, 2019; United Nations, 2013). One mother reported knowing it was wrong to marry off her daughter but believed she would be safer and more respected when married than not, given the state of their community and the fact her daughter could not attend school (Selby & Singer, 2018). There are also some parents who believe that marrying off their children will protect them from sexual violence, because they will be protected by their partners. This is not always the case, however, given that sexual violence is often exacerbated by child marriage as the children are physically underdeveloped and vulnerable (United Nations Population Fund, 2018; United Nations, 2013). In some cultures, the value of a girl’s dowry to be paid goes up as she ages because her childbearing years are decreasing, therefore family members will try to marry her off younger (Selby & Singer, 2018; United Nations Population Fund, 2018).

The Dangers of Child Marriages

Girls who are married young are at risk of sexual violence, physical abuse, HIV, pregnancy complications, and even death (Chakraborty, 2019; End Child Prostitution and Trafficking (ECPAT), 2015; ICRW, n.d.; International Women’s Health Coalition, n.d.; United Nations, 2013; United Nations Population Fund, 2018). Some girls are forced to make themselves sexually available not only to their husbands but also other male family members at any time (ECPAT, 2015). Girls who resist advances from their husbands are at a high risk of sexual violence and verbal or physical abuse from their husbands who may force them into submission (ECPAT, 2015). Moreover, as a result of their lack of physical maturity, child brides are at a high risk for pregnancy complications like obstetric fistula and early or still births, which can sometimes result in death (United Nations Population Fund, 2013). Because of some religious and cultural beliefs, there is a lot of pressure on girls to prove their fertility. Therefore, despite pregnancy complications, girls may be pressured or forced to have frequent or close pregnancies (indicating little control over their family planning) (ECPAT, 2015; United Nations Population Fund, 2013). Finally, when girls are married young and take on wife and mother roles, they no longer have access to education and are put in a place where systems of inequality, poverty, and low levels of education are perpetuated with their female children (ECPAT, 2015; United Nations, 2013; United Nations Population Fund, 2013, 2018; Selby & Singer, 2018).

Source: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2015/08/28/the-saddest-bride-i-have-ever-seen-child-marrige-is-as-popular-as-ever-in-bangladesh/?utm_term=.c9d2924c92fd

Mail Order Brides

A quick google search of “mail order bride” will pull up dozens of websites where a person can find a woman to marry from a foreign country for a fee. The International Marriage Brokers industry is composed of profit driven facilitators of arranged marriages and are often characterized as vectors of harm for unsuspecting women looking to marry (Tahirih Justice Center, 2025). The idea of mail order brides has become mainstream and romanticized through shows like TLC’s 90 Day Fiancé without a proper context for the origins and disparities (i.e., gender, age, class, nationality, violence, immigration challenges, etc.) associated with such arrangements. A mail order bride is a woman “ordered” for marriage by a usually more affluent man. The man pays a broker a fee for the match, and then pays for the travel expenses for the woman to come to him to be married. The brides (or occasionally husbands) are often leaving financially unstable families and/or politically unstable countries in search of a more stable life, which is expected to be found with the husband (Jackson, 2002; Jones, 2011). As the new spouse usually pays for the travel arrangements for the incoming bride (or husband in some cases), the immigrant spouse

Immigration into the United States is complex, expensive, time consuming, and out of reach for many. For those who are privileged enough to access immigration opportunities to the United States and other high income countries, immigration can also place immigrants in vulnerable situations especially as a mail order bride. For instance, the mail order bride is often financially reliant dependent, relocated to a country they do not know the language or customs of (Tyldum, 2013), or worst yet are subjected to threats of violence and actual abuse (sexual, physical, emotional). For instance, a woman who enters into the United States on the fiancée visa (K-1), must legally marry within 90 days after arrival, apply for the Green Card, and remain in the marriage for at least two years before they are granted final permanent resident status (i.e., green card or lawful permanent residence card). (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, 2018). Failure to marry within 90 days of arrival or a divorce before the issuance of a final permanent resident status places the spouse in a precarious legal status (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, 2018), even if abuse is alleged in the relationship.

Precariousness states of existence during the immigration process seems to be inherently embedded in the process–especially in the United States. In 1999, the United States recognized the inherent potential for abuse in arranged marriages through mail order bride companies. Six years later, the International Marriage Broker Regulation Act (IMBRA) of 2005 was enacted. Mail order brides are primarily ordered by men in the U.S., Australia, and Western Europe, and also in areas of Asia that include Taiwan, Korea, and Japan–areas where affluent men can be found (Tyldum, 2013; Yakushko & Rajan, 2017). “Many foreign fiancées or spouses come from Russia, Eastern Europe, Central America, and Asia, the majority coming from the Philippines, through IMBs” (Interiano, 2018, para 3). Exoticism and cultural stereotypes of women from these parts of the world appear to be fueling the International Marriage Brokers (IMB) profitable industry (Interiano, 2018).

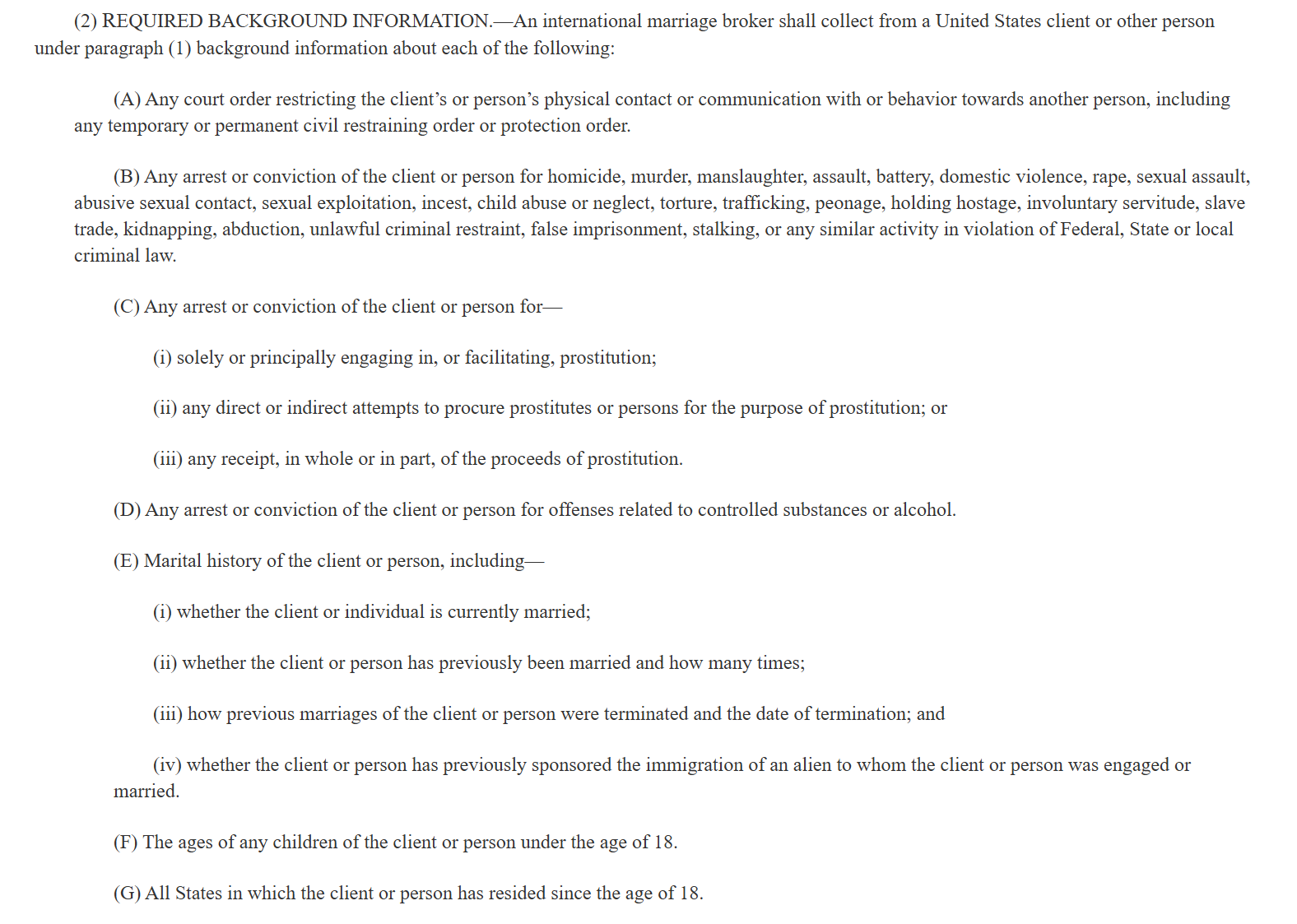

The practice of mail order brides is centuries old, but is more prevalent in the modern day because of the ease of access through the internet (Jones, 2011; Minervini & McAndrew, 2005; Yakushko & Rajan, 2017). In some cases, brides and grooms are genuinely looking for life partners on their own. Yakushko and Rajan (2017) highlight the existence of self-described mail order brides who are older and educated and sought out foreign spouses because cultural norms deemed them undesirable. One study found that women were choosing to date men internationally because they did not like the attitudes toward women from men in their own cultures and believed the values and attitudes toward women from American men would be different (Minervini & McAndrew, 2005). Ironically, the men interested in purchasing brides are often looking for women who embody the exact stereotypes and attitudes the women are trying to escape (Minervini & McAndrew, 2005; Starr & Adams, 2016). Some men are drawn to mail order brides because they feel the women available to them domestically have a lack of traditional family values, are spoiled, and will not be good, caring wives; some also believe Asian women will be timid and caring, Latina women exciting and fiery, and European women refined (Jones, 2011; Starr & Adams, 2016). In many cases, the situation of mail order brides is similar to that of child brides. Both groups of brides are often place in precarious predicaments because of their loss of agency in the process. For instance, the mail-order bride industry is completely unregulated in most places in the world–leaving brides to the mercy of the their sponsoring husbands regardless of their backgrounds (Lloyd, 2020). In the United States, however, the International Marriage Broker Regulation Act (IMBRA) of 2005 requires that a petitioner for a K nonimmigrant visa for a fiancé/fiancée or spouse disclose in-depth information to their international marriage broker about their backgrounds as shown below in Table 1. This type of information on the part of the petitioner (U.S. citizen) is in an attempt to protect immigrating persons from unknown histories, violence, and even death at the hands of those who sponsor their visas. Per IMBRA guidelines, the petitioner sponsoring the mail order bride must offer responses or details related to all of the following items as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Required Background Information IMBRA

International Marriage Broker Regulation Act (2005)–Required Background Disclosures

International Marriage Broker Regulation Act (2005)–Required Background Disclosures

Human Trafficking Connection

As can be seen in the required disclosures from U.S. sponsors, activities regarding trafficking, slave trading, peonage, involuntary servitude, unlawful criminal restraint, and a host of other violent activities often associated with human trafficking are noted as required areas of disclosure. Even with these guardrails in the place in the United States, human trafficking, exploitation and intimate partner violence can still occur and place the unknowing fiancé/fiancée in danger. In fact, this is why the IMBRA was put into place in the first place. The IMBRA is the result of two women as marriage green card holders who were violently killed by their husbands (Moodie & Modine, 2025). As a preventive measure to prevent others from meeting the same fate, IMBRA requires that the U.S. government provide information on the legal rights of the immigrant (via a pamphlet is one way to do this), a criminal background check of the U.S. citizen, and guidance to the immigrant on how to access help if the relationship becomes abusive (Moodie & Modine, 2025). In a compelling testimony by a Georgetown Law Professor, Suzanne H. Jackson writes…

I will refer to the companies as international matchmaking organizations or IMOs rather than “mail-order bride” agencies, even though the term IMO inaccurately conveys gender neutrality and a “match” or some level of equality between the parties. Nothing could be further from the truth: IMOs exist for the benefit of their paying customers: men from wealthy nations, including the United States, Japan and Germany, who want access to women who, most often, have neither economic nor social power. Marketing strategies used by IMOs advertise women as generic to their ethnicity – all Russian women are X, all Asian women are Y, all Latinas are Z – and emphasize that the women they offer (women who are in fact hoping to leave their home countries) will all be “home-oriented” and “traditional” wives. Some companies guarantee women’s availability, others guarantee marriage within a year of subscribing to their service, one even allows a man to remove a woman from the website to prevent competition during a courtship: “Select One, She’s Yours,” promises this company.

IMOs have been linked to criminal trafficking in several ways. They can be nothing more than fronts for criminal trafficking organizations, in which adults and girls are offered to the public as brides but sold privately into prostitution, forced into marriage (including marriages to men who then prostitute them), or held in domestic slavery. Police in the United Kingdom found organized criminal gangs from Russia, the former Soviet Union and the Balkans using the Internet to advertise women for sale to brothels in Western Europe and also to men as “internet brides.” A study by Global Survival Network (GSN) found that most mail-order bride agencies in Russia have expanded their activities to include trafficking for prostitution. European embassies have reported that a number of matchmaking agencies conceal organized prostitution rings victimizing newly arrived Filipina women. Asian groups have used fiancée visas and marriage with a so called “jockey” (an escort bringing women across the U.S. border) to bring women into the U.S. for purposes of prostitution; jockeys have even included U.S. military personnel posted abroad.

IMOs are almost completely unregulated, advertise minors for marriage, and fail to screen their male clients for criminal histories. IMO practices exacerbate problems with false expectations: they require women to complete long questionnaires asking intrusive personal questions, encouraging disclosure by implying or stating that false answers could lead to cancellation of any ensuing immigration benefits. Women are also subjected to medical and background checks, and may assume that participating men are evaluated with the same level of scrutiny. Women from other countries often assume that all governmental agencies in the United States – a country with extraordinary resources and technology – have access to information held by other agencies, that facts asserted in applications for immigration benefits would be checked, and that a man who had been convicted of serious violent crimes would not be permitted to bring a spouse or fiancée into the U.S. from abroad. The industry does nothing, however, to screen male customers: no detailed questionnaire, no check for a criminal record for spousal or child abuse, no formal inquiry as to whether men are already married. Until recently, the U.S. government also did not conduct these inquiries….One commentator in an Internet discussion of the pros and cons of paying for a “mail-order” bride, pointed out that it can be much less expensive to purchase a wife than to pay for prostitution services, which don’t also include free housekeeping and cooking. Men have also used imprisonment and vicious violence to sexually exploit and prostitute young women. One Honduran woman was kept a prisoner – together with the U.S. citizen’s wife – in a man’s home by bars on the windows; another was kept in the house on an ankle chain; one 17-year old from the Philippines was abused, sexually exploited, and then pimped into prostitution.

Testimony of Suzanne H. Jackson, Associate Professor of Clinical Law, George Washington Law School. Human trafficking: Mail Order Bride Abuses. Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate, One Hundred Eighth Congress, Second Session, Tuesday, July 13, 2004

Some researchers argue that there is a disproportionate amount of scholarship dedicated to comparing the mail order bride industry to human trafficking (Yakushko & Rajan, 2017). However, in many cases, brokers are selling people for profit, the girls or women do not know their soon-to-be husbands or the lived reality they are marrying into, and there is a power differential between the bride and her husband (Jackson, 2002; Jones, 2011; Tyldum, 2013). As seen above in Suzanne H. Jackson’s testimony, some mail order brides are indeed victims of human trafficking. Additionally, sometimes the international marriage broker sites are covers for prostitution rings, and act as sites where pimps can buy new girls or women and sell girls and women who are no longer of use to them (Jackson, 2002). Additionally, a precarious immigration status is often used by some husbands and buyers as a way to control their mail order brides, stating that if they report abuse, try to leave the relationship, or do not comply with orders, they will be deported (Narayan, 1995; Jackson, 2002; Weller & Junck, 2014). In the case of child brides, the trafficking is a bit more obvious: families are being paid for the possession of their daughters, and/or children are being sold into dangerous and sexually controlling relationships. In both cases (child brides and/or mail order brides), some women and children are placed in a vulnerable position that involves being sexually exploited through fraud, deception, and coercion, or forced to engage in commercial sex activities, respectively, which are legal elements of human trafficking according to the Trafficking Victims Protection Act. Sex trafficking is a human rights violation in the United Nations’ definition of trafficking and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 2003; United Nations, 1948).

Legislation

Child marriage not only meets the United Nations’ definition for human trafficking, but it is also a human rights violation in the context of several international rulings, such as: Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948); Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery (1956); Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage, and Registration of Marriage (1964); International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (1966); the Inter-American Convention on Human Rights (1978); Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (1981); Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989); and Vienna Declaration on Programme and Action (1993) (Girls Not Brides, n.d.). Reviewing the years of some of these documents shows how long child marriage has been an international issue. The United Nations, UNICEF, and the world YWCA have initiated efforts to end child marriages by 2030 by promoting proven practices in reducing child marriages like: increasing girls’ access to education and healthcare, ensuring parents are informed on the risks and dangers associated with child marriage, fighting poverty, and strengthening minimum age of marriage laws (United Nations, 2013; UNICEF, 2018; United Nations News, 2016). Additionally, as of June 2019, the deputy grand Iman of Al Azhar, the highest authority in Sunni Islam, issued a fatwa (a formal ruling in Islamic law) that all children, especially girls, must be at least 18 years of age and consenting before being married (Mogoatlhe, 2019). Sunni Islam accounts for about 75-90% of Muslims globally (Mogoatlhe, 2019), which means the fatwa has the potential for a widespread impact. Unless there is a significant increase in not only efforts but also efficacy, however, it is unlikely that the 2030 goal will be met (UNICEF, 2018).

Mail order brides legislation is a bit more difficult because the human rights violations within it are more covert, especially with the growth of the internet being a tool in partner-finding and the romanticizing of transnational relationships through shows like TLC’s 90 Day Fiancé. The United States included provisions specific to mail order brides in the Violence Against Women Act and enacted the International Marriage Broker Regulation Act in an effort to prevent exploitation of international brides by American men (National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV), 2019). Reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act expired in February 2019, and, as of March 2019, was awaiting approval from the Senate. It was later renewed in late March 2022 and is in effect until fiscal year 2027 (Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2022). The efficacy of the International Marriage Broker Regulation Act is difficult to assess (NNEDV, 2019; Sims, 2015) and still has not been fully implemented since its 2005 enactment. For instance, the one provision of the legislation is that the content would be available in several languages so that it is understood by those who speak languages other than English. At this time, it is only available in English (Interiano, 2018). The Philippines enacted an anti-mail-order-bride law too, in which it is illegal to facilitate the marriage of Filipina women and foreign men as a business (Sims, 2015). The law has largely been ineffective with the use of the internet for marriage brokering, and for lack of designation of an enforcement agency by the Philippine government (Sims, 2015). Alternatively, Taiwan’s legislation has been effective. Since 2003, Taiwan has enacted strict laws controlling advertisements of mail order brides, setting minimum age requirements and spousal age difference limits, and began closely monitoring marriages with foreign brides in an effort to combat human trafficking and prostitution (Sims, 2015). As a result, marriages involving foreign brides has dropped 40%, mail order bride industry profits have been affected by the age limits, and Taiwanese police have begun offering trainings to recognize human trafficking (Sims, 2015).

Action

Social workers are charged with advocating for social, economic, and political justice (National Association of Social Workers, 2017). Therefore, in the case of child brides, it is imperative that micro-practice social workers engage in educating individuals, parents, and communities on the warning signs of intimate partner abuse, the physical and emotional consequences of child sexual abuse, and the dangers of pregnancy and child birth on young, underdeveloped girls (Sossou & Yogtiba, 2009). On a macro level, social workers must advocate for girls’ rights to pursue education, 18 and over marriage laws, sex and reproductive health education, and domestic violence prevention. UNICEF (n.d.) also highlights the importance of: more research on this topic to create a strong evidence base for policy, programming, and tracking progress; shifting social expectations of young girls; strengthening services offered to victims of child marriage or those at risk; and tackling the challenges that perpetuate child marriage like gender inequality, lack of education, and poverty. All of these are areas where a social work presence and practice lens can be beneficial. For mail order brides, it is important that the Violence Against Women Act is renewed in 2019 and continually renewed in the future. Additionally, social workers working with immigrant women need to know the signs of abusive relationships, sex trafficking, and prostitution, and know resources to assist women in leaving abusive relationships while protecting their immigrant status.

Quiz

Now, let’s shift gears and turn to a case study.

AMIRA

Amira was a 14-year-old, oldest child of four. Amira’s parents were married when her mother was 13 and her father was 20 years old; similar to each of their parents. Amira’s mother never attended school and had her first child, Amira, at the age of 15. Unlike her mother, Amira was able to attend school until she was 13 years old. At about the age of 12 or 13, Amira hit puberty, and her parents were concerned about her walking to school and attracting male attention because of her developing body. Since Amira was then just staying home, her parents felt it was time for her to learn wifely duties and to start a family of her own. Amira’s parents had known Adeel’s parents since they were young, and knew Adeel would be able to care for Amira financially, as he was in his 20’s and taking over his family’s business. Amira and Adeel’s parents arranged for the marriage of Amira to Adeel before her 15th birthday. Amira met Adeel a few times with both of their families before their marriage, but did not know him well. After their marriage, Amira moved in with Adeel and took care of their home until she became pregnant with their first child shortly after turning 15. Amira, now 21, and Adeel, in his early 30’s, are about to have their third child.

Summary of Key Points

- Child brides and child marriage are persistent issues in violation of several international and national legislation efforts affecting millions of girls every year. Initiatives have begun to end child trafficking by 2030, but will need to increase exponentially if this goal is to be achieved.

- Mail order brides is a covert and hotly debated form of human trafficking. Some scholars claim there is an over emphasis on the trafficking and prostitution cases and not enough on the instances of educated women entering into international marriages willingly. Nonetheless, there are instances of mail order brides that are trafficking, therefore attention and prevention efforts need to be directed toward this issue.

- Both child brides and mail order brides are often coerced into forced relationships, have limited protections in place for their safety, and are sold for profit into relationships.

Supplemental Learning Materials

Books

A True Story: A Father’s Betrayal by Gabriella Gillespie

American Child Bride: A History of Minors and Marriage in the United States by Nicholas Syrett

Films

Tall as the Baobab Tree (2012); Dukhtar (2014)

Websites

Globalcitizen.org

Girlsnotbrides.org

Care.org

Stopthetrafik.org

Articles

Aptel, C. (2016). Child Slaves and Child Brides. Journal of International Criminal Justice, 14(2), 305-325. DOI: 10.1093/jicj/mqv078

Greene, M. (2014). Ending Child Marriage in a Generation: What Research is Needed? Ford Foundation. https://www.fordfoundation.org/media/1890/endingchildmarriage.pdf

Hedayat, N. (2011). What is it like to be a child bride? BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-15082550

International Center for Research on Women. (2013). Solutions to End Child Marriage: Summary of the Evidence. https://www.icrw.org/publications/solutions-to-end-child-marriage-2/

Naveed, S. & Butt, K. (2015). Causes and consequences of child marriages in South Asia: Pakistan’s perspective. South Asian Studies, 30(2), 161-175. http://pu.edu.pk/images/journal/csas/PDF/10%20Khalid%20Manzoor%20Butt_30_2.pdf

Peyton, N. (2017). 27 African Countries Just Met and Agreed to End Child Marriage. Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/african-child-marriage-ending-meeting/

References

Chakro, R. (2019). Child, not bride: Child marriage among Syrian refugees. Harvard International Review. https://hir.harvard.edu/child-not-bride-child-marriage-among-syrian-refugees/

End Child Prostitution and Trafficking. (2015). Thematic Report: Unrecognised Sexual Abuse and Exploitation of Children in Child, Early and Forced Marriage. https://www.ecpat.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Child%20Marriage_ENG.pdf

Girls Not Brides. (n.d.). Provisions of International and Regional Instruments Relevant to Protection from Child Marriage. https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Intl-and-Reg-Standards-for-Protection-from-Child-Marriage-By-ACPF-May-2013.pdf

Girls Not Brides. (2019). Child Marriage Around the World. https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/where-does-it-happen/

Interiano, G. (2018). Domestic violence and the “mail order bride” industry. Immigration Prof Blog. https://lawprofessors.typepad.com/immigration/2018/04/domestic-violence-and-the-mail-orde

International Center for Research on Women. (n.d.) Child Marriage Facts and Figures. https://www.icrw.org/child-marriage-facts-and-figures/

International Women’s Health Coalition. (n.d.). The Facts on Child Marriage. https://iwhc.org/resources/facts-child-marriage/

Jackson, S. H. (2002). To honor and obey: trafficking in “mail-order brides”. George Washington Law Review, 70(3), 475-569. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/gwlr70&i=487

Jones, J. (2011). Trafficking internet brides. Information & Communications Technology Law, 20(1), 19-33. DOI: 10.1080/13600834.2011.557525

Lloyd, K.A. (2020). Wives for sale: The modern international mail-order bride industry. Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business, 20(2), 341-367.

Minervini, B. & McAndrew, F. (2005). The mating strategies and mate preference of mail order brides. Cross-Cultural Research, 5(X), 1-20. DOI: 10.1177/1069397105277237

Mogoatlhe, L. (2019). The Highest Authority in Sunni Islam Just Declared an End to Child Marriage in Africa. Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/end-child-marriage-sunni-islam-africa4girls/

Moodie, A., & Modine, H. (2025, February 4). International Marriage Brokerage Regulation Act (IMBRA). https://www.boundless.com/immigration-resources/imbra-explained/

Narayan, U. (1995). “Male-order” brides: Immigrant women, domestic violence and immigration law. Hypatia, 10(1), 104-119. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/stable/3810460

National Association of Social Workers. (2017). Code of Ethics. https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

National Network to End Domestic Violence. (2019). Violence Against Women Act. Policy Center. https://nnedv.org/content/violence-against-women-act/

Organization of American States. (1969). American Convention on Human Rights, “Pact of San Jose”. Costa Rica. https://www.oas.org/dil/access_to_information_American_Convention_on_Human_Rights.pdf

Selby, D. & Singer, C. (2018). Child Marriage: Everything You Need to Know. Global Citizen. https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/child-marriage-brides-india-niger-syria/

Sims, R. (2015). A comparison of laws in the Philippines, the U.S.A., Taiwan, and Belarus to regulate the mail order bride industry. Akron Law Review, 42(2), Article 7. Retrieved from http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol42/iss2/7

Sossou, M., Yogtibo, J. (2009). Abuse of children in West-Africa: Implications for social work education and practice. British Journal of Social Work, 39, 1218-1234. DOI: 10.1093/bjsw/bcn033

Starr, E. & Adams, M. (2016). The domestic exotic: Mail-order brides and the paradox of globalized intimacies. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture & Society, 41(4). DOI: 0097-9740/2016/4104-0010

Tahirih Justice Center. (2017). Child Marriage in the United States: A Serious Problem with a Simple First Step Solution. Retrieved from https://www.tahirih.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Tahirih-Child-Marriage-Backgrounder-2.pdf

Tahirih Justice Center. (2025). International marriage brokers: Brokers may put women at risk. https://www.tahirih.org/what-we-do/policy-advocacy/international-marriage-brokers/

Tyldum, G. (2013). Dependence and human trafficking in the context of transnational marriage. International Migration, 51(4), 103-115. DOI: 10.1111/imig.12060

UNICEF. (n.d.). Preventing Child Marriage. https://www.unicef.org/eca/what-we-do/child-marriage

United Nations. (2003). Protocol to prevent, suppress, and punish trafficking in persons. (Resolution 55/25). https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/what-is-human-trafficking.html#What_is_Human_Trafficking

United Nations. (2013). Child Marriages: 39,000 Every day – More than 140 million girls will marry between 2011 and 2020. Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth. https://www.un.org/youthenvoy/2013/09/child-marriages-39000-every-day-more-than-140-million-girls-will-marry-between-2011-and-2020/

United Nations Economic and Social Council. (1956). Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery. (608 [XXI]) https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/SupplementaryConventionAbolitionOfSlavery.aspx

United Nations General Assembly. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (217 [III] A). http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

United Nations General Assembly. (1964). Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage, and Registration of Marriage. (1763 [XVII] A). New York. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/MinimumAgeForMarriage.aspx

United Nations General Assembly. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. (2200 [XXI] A). https://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/unts/volume%20999/volume-999-i-14668-english.pdf

United Nations General Assembly. (1966). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. (2200 [XXI] A). https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cescr.aspx

United Nations General Assembly. (1979). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. (Resolution 34/180). https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/

United Nations General Assembly. (1989). Convention the Rights of the Child. (Resolution 44/25). https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx

United Nations General Assembly. (1993). Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. (Resolution 48/121). Vienna. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/Vienna.aspx

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. (2018). Child Marriage: Latest Trends and Future Prospects. https://data.unicef.org/resources/child-marriage-latest-trends-and-future-prospects/

United Nations News. (2016). New UN initiative aims to protect millions of girls from child marriage. https://news.un.org/en/story/2016/03/523802-new-un-initiative-aims-protect-millions-girls-child-marriage#.Vt8pqfkrK71

United Nations Population Fund. (2013). Motherhood in Childhood: Facing the challenge of adolescent pregnancy. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/EN-SWOP2013-final.pdf

United Nations Population Fund. (2018). Child Marriage. https://www.unfpa.org/child-marriage

United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2018). Visa for fiancé(e) of U.S. citizens. https://www.uscis.gov/family/family-of-us-citizens/visas-for-fiancees-of-us-citizens

Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2022. S.3623.Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2022

Weller, S. & Junck, A. (2014). Human Trafficking and Immigrant Victims: What Can State Courts Do?. A Guide to Human Trafficking for State Courts, pages 47-77. http://www.htcourts.org/wp-content/uploads/Full_HTGuide_desktopVer_140902.pdf

World Policy Analysis Center. (2015). Fact Sheet: Assessing National Action on Protection from Child Marriage. https://www.worldpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/WORLD_Fact_Sheet_Legal_Protection_Against_Child_Marriage_2015.pdf

Yakushko, O., & Rajan, I. (2017). Global love for sale: Divergence and convergence of human trafficking with “mail order brides” and international arranged marriage phenomena. Women & Therapy, 40, 190-206. DOI: 10.1080/02703149.2016.1213605