5. Offer Forums Where Community Issues Can Be Identified and Addressed.

Offering problem-solving forums that engage community members can be a powerful strategy — especially when offered during calmer periods, when people are more likely to participate candidly, but respectfully. A number of organizations have created models for doing so.[1]

Why take this step?

People may escalate their actions when they perceive that no action was taken – nothing changed – after they had made their concerns known. In some cases, this perception may be inaccurate—public officials may have taken action but failed to communicate it effectively to those who raised the concern.

The shape of the forum will depend both on its goal and the level of emotions of those who will attend. For example, a large town hall may be vulnerable to disruption by groups seeking publicity rather than solutions or by speakers who tend to insult rather than explain. A series of small groups or an assembly of invited participants might work in such situations. Planners who have been listening to residents can work with seasoned facilitators to design a format that encourages thoughtful engagement and constructive dialogue.[2] Research suggests that well-planned facilitated dialogues can build understanding and empathy across both religious and political divides, thus reducing polarization.[3]

Of course, it takes courage to acknowledge that an issue or problem – particularly a complex one – might exist. But doing so can sometimes form the foundation for participants to engage in a sustained, detailed discussion that enables a community to address underlying issues effectively and to develop a more comprehensive, pro-active plan to ameliorate their recurrence.

“The following sequence is typical of [unmanaged] public disputes: One or more parties choose not to acknowledge that a problem exists. Other groups are forced to escalate their activities to gain recognition for their concerns. Eventually everyone engages in an adversarial battle, throwing more time and money into ‘winning’ than into solving the problem.” – Susan Carpenter & W.J.D. Kennedy, public policy mediators.[4]

Problem-solving can also continue during times of unrest. For example, public officials might make decisions—such as relocating a monument—that address underlying concerns and reduce protest intensity. Mediators can convene groups, or act as intermediaries to bridge groups, that include both those with resources and those with deep understanding of the issues to engage in collaborative problem-solving.

People may take to the streets because they seek more attention or effort to resolve a problem. Their demands may also reflect an attempt to attract and motivate a crowd through requests that can be embodied in a short slogan. When public officials and community leaders engage with them to address the underlying interests that led them to seek attention, these initiatives may alleviate tensions and reduce the need for continued unrest.

Experienced community-wide mediators—such as those formerly with the U.S. Department of Justice Community Relations Service—can play a vital role. They often have connections to national organizations aligned with local concerns and to community leaders who have navigated similar conflicts elsewhere.

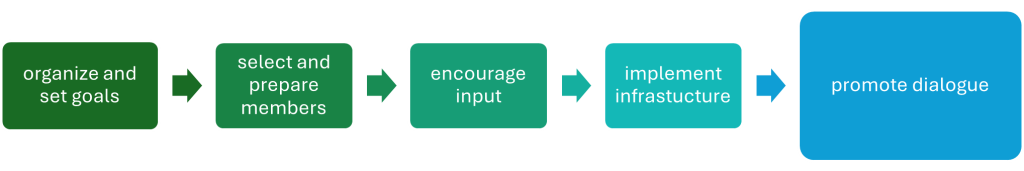

How to take this step

CHECKLIST: Offer Forums to Identify and Address Community Concerns

- Regularly convene meetings of the advisory groups with key public officials.

- Provide deliberative forums in which people can raise concerns with public officials and explore possible actions to be taken. Developing the location and timing for such forums to enable broad-based community accessibility may require holding multiple sessions in different locations and at various times of the day and evening, with the logistics for all such gatherings being widely and effectively publicized. The National Civil League has developed suggestions for “Better Public Meetings.”[5]

- Conduct a citizen assembly, using a lottery process that identifies a random and representative sample of community residents who are then invited to share experiences and suggest ideas or possible actions to members of the planning committee. The National Civic League offers resources for shaping an effective citizen assembly and other community meeting formats, Civic Genius.[6]

- Utilize experienced and diverse mediators, facilitators, or moderators to organize and execute public conversation forums, since those persons then take charge of handling administrative matters regarding meeting logistics (time, locale, microphones, use of technology such as smartphone polling, and the like), develop and monitor compliance with acceptable ground rules for engagement, and, during the session, support, reframe and in other ways assist people to talk about challenging issues in constructive ways. Meeting organizers should arrange for conducting resident/participant evaluation of such meetings, using such methods as paper surveys, on-line evaluations, and the like. The facilitators –- or other persons so designated during the forum –- can develop a written report summarizing the meeting processes, results (including areas of agreement and disagreement), and actions to be taken. The report can be made available in some form for public review.

- Announce any decisions related to concerns raised, including any process created to hear the community members’ concerns.

- Offer meaningful ways for those engaged to pursue their interests, such as taking training to serve as parade marshals,[7] engaging in substantive discussions about how resolve the issues underlying the unrest or planning a vigil.

ILLUSTRATION | Fertile, MN

Mediators can convene and facilitate a broadly representative group in ways that address underlying interests, even if public officials will not accede to the demands.

In Fertile, Minnesota, in 2011 some community members hurled a series of slurs and engaged in acts of petty vandalism against members of an Amish community; those actions culminated in some individuals setting fire to a barn on an Amish farm and killing some of the calves housed within it. Amish leaders asked that the alleged arsonists not be prosecuted, as forgiveness was a central tenet of their religion, and the Amish community re-built the barn over the course of a week, using only manual labor and a chainsaw. While the Amish were unlikely to engage in community unrest, there was a possibility that they would not report crimes in the future if their request was not met, thus perhaps encouraging those who wanted to perpetrate crimes against this community to repeat the same or similar actions. Granting the Amish request posed a problem for law enforcement, however, as victims do not determine whether someone should be prosecuted. The U.S. Department of Justice Community Relations Service (“CRS”) convened a dialogue among the Amish community, police, and members of the broader community.

CRS reported:

“While the police did not accede to the request not to prosecute, the group suggested dealing with the underlying issues through increased police patrols near Amish farms as well as arranging events that helped non-Amish members of the community understand the Amish religion and way of life as a way to reduce future hate crimes. The ability to convene a problem-solving dialogue to deal with underlying interests, even when a demand cannot be granted, can be crucial to being responsive.”[8]

ILLUSTRATION | Costal Communities, TX

Using conciliation/mediation can help residents resolve the problems that led to unrest.

Former CRS administrators, Bertram Levine and Grande Lum, recount the role played by a CRS conciliator during unrest in Texas coastal towns in the 1980s. When the CRS conciliator arrived, ethnic tensions had already resulted in targeted deaths and fires. Marches by extremist white supremacist groups threatened. The governor had sent the National Guard to one community to restore peace.

The CRS conciliator listened to understand the underlying problems. A few years earlier, church organizations had settled Vietnamese refugees with shrimp fishing experience in Texas shrimp fishing communities. The refugees quickly enjoyed success, while long-time local shrimpers experienced decreased income. The refugees lived more frugally, shared resources among extended families, and worked longer hours than the long-time local fishers. Unable to speak English, the refugees used their Vietnamese fishing customs, which violated federal and state laws designed to protect from over-fishing and clashed with local norms.

The CRS conciliator began working on enhancing communication and assembling the resources needed to address the problems. He convened meetings with representatives of groups that, together, might contribute to the problem-solving as well as long-term and refugee fishers. Potential resource providers included the faith-based refugee organizations, law enforcement, state and federal regulators, and a state immigration task force. As the result of the resource group’s connections and contributions, explanations of regulations and fishing customs were published in Vietnamese, refugees were offered language instruction, and those seeking to leave the fishing industry were provided vocational training.

Through mediation spanning weeks, the CRS conciliator separately organized a council of old and new shrimpers. This council enhanced understanding between both groups of shrimpers, dealt with grievances, and addressed other community issues. Over time, tensions receded. CRS was able to help other shrimping communities where conflicts had not yet produced unrest, sharing the problem-solving and mediation approaches used in the first communities experiencing unrest.[9]

- The Kettering Foundation lists a number of these organizations and forum formats. https://deliberative-democracy.net/portfolio/kettering-foundation/. ↵

- An experienced community facilitator might help with the design of the process and be willing to facilitate the meeting. A local community mediation program might help locate the facilitator. The National Association for Community Mediators, (602) 633-4213, can connect you to a program near you. ↵

- Johanna Sullivan, Finding Identity Complexity Through Dialogue, 31(1) Peace and Conflict Studies Article 5 (2024) (noting the dialogue series between Jews and Muslims and between groups associated with different political groups helped group members see "the parts of other groups that are within themselves, developing inclusive relational identities that can allow for perspective-taking and empathy”). ↵

- Susan L. Carpenter & W.J.D. Kennedy, Managing Public Disputes 11 (2001). ↵

- National Civic League, Democracy Innovations for Better Public Meetings, https://www.nationalcivicleague.org/center-for-democracy-innovation/democracy-innovations-for-better-public-meetings/ ↵

- National Civic League, Civic Genius, https://www.nationalcivicleague.org/civic-genius/. ↵

- Community Relations Service, Event Marshals: Maintaining Safety During Public Events. (last modified September 5, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/crs/our-work/training/event-marshals. ↵

- Divided Community Project. Planning in Advance of Community Unrest 19 (2d ed. 2020), https://kb.osu.edu/handle/1811/106212. ↵

- Bertram Levine & Grande Lum, America’s Peacemakers 246-250 (2020). ↵