7. Communicate Constructively when Community Tensions Rise

This chapter begins several chapters devoted to divisive events – both preparation and responding during these times. When unrest threatens, the leaders’ first communications can frame and shape how events unfold. Without intensified and timely listening and messaging, trust may plummet, immediate needs go unmet, and misinformation take hold. Conflict can escalate. Preparing in advance allows leaders to delegate tasks quickly and communicate constructively at this pivotal moment.

This chapter begins several chapters devoted to divisive events – both preparation and responding during these times. When unrest threatens, the leaders’ first communications can frame and shape how events unfold. Without intensified and timely listening and messaging, trust may plummet, immediate needs go unmet, and misinformation take hold. Conflict can escalate. Preparing in advance allows leaders to delegate tasks quickly and communicate constructively at this pivotal moment.

This chapter is divided into two parts:

A. Check in with each part of the community.

B. Communicate with residents with the speed and the content they need during community conflict, using trusted messengers and communications methods that will reach them.

A. Check in with Each Part of the Community

Consider asking staff to check in with key parts of the community while other staff are working on communications, problem-solving, and demonstration preparations. The check-in is in equal parts to listen, to meet immediate needs to the extent feasible, and to identify messengers trusted by each part of the community.

Why take this step?

The simple act of checking in with various parts of the community has several constructive effects. When the results are given to leaders and communications staff, this allows leaders to demonstrate their appreciation for how residents are experiencing the event and to offer compassion when they learn that residents are suffering. By accurately summarizing community reactions, a leader also helps a divided community begin to understand why others have deeper concerns than they do. Because reactions to an event might have a “this is the last straw” character, it’s also important to make an accurate assessment because doing so both allows leaders to identify such residents’ needs as safety risks and respond to them quickly. Leaders’ abilities to reflect this assessment in communications with the broader community may help other residents understand the history or related concerns that explain their fellow residents’ more intense feelings.

In addition to these benefits, checking in may avert a major misstep. For example, suppose antisemitic events are rising nationally and someone projects a swastika on several city buildings. To point out the added emotional toll this takes for Jewish residents but fail to mention that the swastika historically has also been a hate symbol targeting persons of color might cause the latter to wonder if their leaders have even a clue about their circumstances.

Checking in allows you to communicate with those who have not read official messages or have been misled by false rumors. It affords an opportunity to establish rapport and to identify individuals (e.g., influencers and allies) who might be willing to issue constructive statements themselves (e.g., importance of pursuing goals peacefully) or help to disseminate messages.

National groups with an interest in the conflict may arrive with different goals and plans than the local groups with similar interests. Thus, checking in with them may expose additional fault lines and scenarios important to preparation.

During local mass crowd events, state and federal public officials may be asked about what is occurring on the ground. Keeping in touch with them about plans may enable them to answer the media questions with current and accurate information. That may also avert their need to promise to send in additional law enforcement or take care of the situation in ways that might conflict with local plans.

CHECKLIST: How to Take this Step

A number of approaches might be helpful:

- Contact those most affected – both directly and indirectly – to listen and offer empathy, help, and ways to stay in touch.

- Engage with those persons who are influential with the groups involved in the conflict, hearing interests and offering ways to express themselves safely.

- Listen to those with a finger on the pulse of each part of the community to gain an understanding of how they are experiencing the conflict and offer to stay in touch with them. These contacts might include, for example, leaders from the business, law, civil rights, and faith communities; from nonprofit and youth organizations; social media and other influential individuals. Your city officials and law enforcement may already have citizens advisory committees that can make this easier.

Other staff might engage in research:

- Watch the news and social media on an ongoing basis for reactions, emotion levels, false narratives, and proposed actions.

- Reach out to experts with third-party neutral intervention and dispute resolution expertise, such as the Community Relations Service,[1] regarding goals and strategies of any national groups likely to engage in the conflict.

- Consider outside capacity as necessary, including from local community mediation and conflict resolution centers,[2] academic institution dispute resolution programs like the Divided Community Project,[3] some state agencies, peacebuilding organizations, and civic engagement facilitators.

Still other staff might brief state and federal public officials about plans, hear any concerns, and continually stay in touch as events unfold.

To make sure that all persons who need the information will have it in a timely way, develop a contact point – someone who will regularly share the information learned from contacts with other staff working on these issues. Checklists that can be distributed to staff assigned to each contact follow below.

CHECKLIST: Touching Base During Community Conflict

As you touch base with each person and record what you learn, please also offer nonjudgmental empathy for the ways that they have been affected and consider whether there are resources to meet any immediate needs they raise. Feel free to offer public information about the situation and correct false rumors. If they plan to take action, such as a march, can you interact with them in ways that contribute to increasing participants’ safety?

For those members of the group directly impacted by the triggering incident or conflict, you might ask them the following questions that focus on their reactions:

- Concerns (and do they feel safe?).

- Type and intensity of emotions.

- How recent concerns relate to past ones.

- What change (if any) they seek.

- Others who have been affected by this.

- What they wish other residents understood about this situation.

- How they might want to be involved with community leaders or others seeking safe and impactful ways to achieve change.

For members of groups who, though not personally impacted, seek to influence how the conflict is resolved:

- Ask the questions above, plus:

- Why they care about the conflict.

- What plans they have formed to express their views.

For those who are influential with or in touch with a portion of the community:

- What they are hearing about this group (leaders, needs, concerns, emotions, plans).

- What they recommend that local leaders do.

- Whether they would be open to staying in touch and consider joining community leaders in joint statements on matters on which they agree (e.g., safety, keeping protests peaceful, reaching their groups with information).

CHECKLIST: Scanning Social Media to Keep a Finger on the Pulse of the Community

Areas of concern and intensity of emotions can change quickly, be redirected or amplified by a new incident, an influential voice, or even a false narrative. As you scan social media, please be attentive to the moods and needs of the community.

- Identify keywords and hashtags used by those concerned with the current conflict (and which you might use to get information to them):

- Consider categorizing posts in terms of —

- Types and intensity of emotions.

- Changes in emotion.

- Any concerns about safety or other distress and any resources they may need.

- What they are most upset about.

- What change they would like to see.

- Any plans they are making to achieve the changes they seek.

- What types of social media are used most frequently by particular groups (young people, etc.), so that leaders can use the same platform to communicate information related to the conflict.

- Any indications that national groups or groups with unrelated causes may be getting involved.

- Off-shore interests that are posting about the conflict.

- AI-generated or manipulated audio, videos and images (“deepfakes”) that appear authentic but are malicious attempts to deceive.

- False narratives or conspiracy theories circulating.

ILLUSTRATION | A western community

Identifying, contacting, and engaging key groups in anticipation of mass crowd events

In a medium-sized city with changing demographics, a video of police officers hitting and pushing a hand-cuffed Black teen triggered outrage. Community leaders worried about not only violent reactions as the criminal case proceeded against the two police officers but also, due to tensions between Black and Latino gangs located in various neighborhoods, the escalation of inter-gang violence. The then-Community Relations Service (CRS) regional director, Ron Wakabayashi, working with eight CRS conciliators, conducted a community assessment with the goals of identifying the range of possible reactions and assessing those persons or groups with whom to engage in preparations for and communications about efforts to manage mass crowd events or gang fighting. Their list of persons and groups whom they identified included: those reacting in grief, hurt, or anger to the police incident; groups likely to make demands or organize protests; the gangs; community and national organizations who advocated for law enforcement change or for a particular community; and opportunists who might seek to use the event for ideological, economic, or personal objectives. CRS conciliators were then assigned to contact a particular individual or group based on the conciliator’s likely ability and credibility to connect with them.

After synthesizing the results of their having made these contacts, CRS conciliators were able to identify key influencers and the ways that people received and trusted information. Their findings included, for example, the influence of: a Black-owned radio station; faith institutions and their outside signage; gangs; and schools. They learned of special concerns in the event a protest occurred, including businesses that might close or add security if they knew in advance that a protest might occur, and schools that would want to time the release of students from school buildings and guide them to various exit routes to keep students safe if marches were occurring.

CRS was able to help these groups develop relationships with one another, such that a group of community representatives, including both gang members and law enforcement, began meeting regularly, staying in touch, and finding ways to contribute to a peaceful resolution. This group could identify and share key dates for mass crowd events, such as the day the jury returned its verdict in the trial of the police officers. They could organize alternative ways for various affected persons to reach their goals, such as engaging in planning a vigil or acting as ambassadors before and during protests.

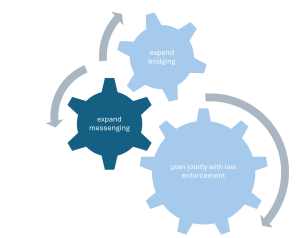

B. Communicate with Residents with the Speed and the Content They Need During Community Conflict, Using Trusted Messengers and Communications Methods that Will Reach them.

When unrest threatens, people grasp for information from the sources they trust or are easily accessible to them. Being ready to communicate quickly and to be in touch with their usual information sources requires some preparation.

Why take this step?

Checking in with various parts of the community, as just discussed, will help to get the right tone, content, and messengers for communications. Unfortunately, it may not always be feasible to wait for this process to be concluded before acting. Residents may want information urgently and will likely lose trust in leaders who do not provide that for them. Also, false narratives that circulate broadly will be more difficult to dislodge later. So, within minutes, not days, leaders can communicate what they know at that time, but indicate that as more information arrives, their communications with residents will continue.[4] Continuing communications will be reassuring to those anxious to know more about what is going on and serve to help them realize that leaders are competently and thoughtfully managing this crisis. Moreover, additional messages will reach a broader audience. Underlining the importance of not treating a deep concern as “business as usual, Norton Bonaparte, City Manager, Sanford Florida, noted, “People don’t care what you know, until they know that you care.”

During a conflict, people may not trust official sources or take time to read information from traditional news sources. This suggests considering not only the substance of the message but also the variety of messengers who might be engaged to convey at least part of the message. For example, while disagreeing with officials on the matter at issue, leaders of various non-governmental groups may be willing to urge protestors to engage in heart-felt, but nonviolent methods of expression and to transmit to their group members facts about where and how people can demonstrate safely.

Another way to expand those reached is to broaden the ways that the message is distributed. Social media may reach more residents much more quickly.

How to take this step

A number of people may be drafting communications and doing so quickly. You might hand out the checklist below, or one you adapt to the circumstances, to such people.

CHECKLIST: Communicating About an Incident or Issues of Deep Concern to Community Residents

Regarding the substance of the communications:

- What has happened, to the extent known (with attention to what the public would want to know), and how updates will be communicated.

- What has been done to ensure the public’s safety and reassurance in the face of unnecessary anxiety.

- What has been done to support those most directly affected.

- Explanations of how some people have been affected and what related history might be considered by these persons, with the aims of showing compassion and helping residents understand and support each other. These explanations need to be done authentically, perhaps setting aside the official way of speaking.

- What decisions have been made and who is accountable for implementing them.

- Who will be consulted and what values will be applied in making future decisions (e.g., “In interacting with large demonstrations, we will always maximize the opportunities for expression and the convenience of other residents to the degree consistent with the safety of all.”).

- Frames the issues in reference to community values (e.g., “a community of people who care about each other….”) and in terms of longer-term underlying issues as well as immediate concerns (e.g., “This attack targeting an Asian American understandably revives fears stemming from several attacks on our Asian American fellow residents during the pandemic…”).

- Affirms freedom of expression while underscoring expectations that residents will act with regard to others’ desires to be respected, feel safe, and express themselves.

- Counters exaggerated or untrue narratives that are circulating, using specificity about the facts and offering the true narrative.

- What residents might do related to their concerns in a way that has impact and is in a safe environment.

Regarding potential messenger(s) for each message:

- Who is trusted and influential with each group?

- Who will convey the importance of the matter?

- Will these persons join together or speak in a series to convey a positive community-wide attitude?

- Are there trusted experts who might help explain?

Regarding the manner for conveying the message:

- Consider a method other than a press conference-type statement[5] (e.g., a vigil attended by city officials, civil rights, business, faith leaders, etc. and with photos published afterward; a Q & A with various leaders).

- Consider using various social media and other sources of news used by residents.

- Identify and use a website that will be frequently updated with information needed by residents and to post statements.

- Repeat messages to reach people who consult their media infrequently.

Special issues that may arise with drafting statements to the public include:

Targeted hate incidents? It’s important in terms of safety and community trust to:

- be candid about what occurred and the harm that it has caused,

- reaffirm community values when condemning it,

- reference the incident while trying not to provoke additional violence by providing too much publicity to the perpetrators or blaming a group with a similar ideology as the perpetrators,[6] and

- announce what is being done to keep safe those who might now be anxious.

Anticipate and pre-bunk potential lies? Think about people with a motive to circulate false information. The motive might be political, gaining attention to a social media site, or greed. After a divisive incident, attempts to escalate the conflict even come from off-shore accounts. Warning the community in advance can be even more productive than trying to counter afterward.

Counter Inaccurate rumors? If not addressed immediately and with credible detail, bad actors and social media bots will amplify the false narratives. (One possible response: “We are hearing XYZ. That is false. Here are the facts….. which you can read more about here.”) People are drawn to narratives (thus, to conspiracy theories), so place the accurate facts within an accurate narrative.

Residents demonizing those on the “other side”? It is valuable to model and encourage respectful interaction, thereby, for example, avoiding calling an entire crowd “criminal,” attacking individuals by disclosing criminal records, etc. While the latter is an understandable human reaction after violence, a more constructive response that helps people view each other as fellow residents might be: “In among the hundreds of our fellow community members, including families with small children, who walked peacefully to express their earnest views, there were about a dozen persons who threw rocks at police, placing others at risk of harm and violating the law. These persons were arrested.”

Fear that mistakes in using particular framing or words will promote backlash? If not accustomed to describing something (for example, a demonstration related to the violence in the Middle East), you might ask an expert in the field to quickly look over the proposed wording (e.g., “war?” “aggressor?”).

Defending past decisions? Take care not to seem defensive, as it creates a public versus community feel to the communication. Emphasizing that public officials serve and are part of “our community” might be better received. Seek feedback for improving.

Discuss advocates’ “demands”? In general, it may be helpful to focus on identifying and discussing underlying interests rather than voiced positions. Nonetheless, if you can explain why it is simply not possible to grant a particular demand and you believe that the readers will understand that is the case, you can explain that (e.g., “Protesters have asked that [insert public entity] sell all investments in [insert nation]’s companies, but doing so is prohibited by state law.”).

ILLUSTRATION | Boise, ID

A public statement that includes candor about targeted violence, reminder of values and peaceful actions of most people, condemnation of the violence.

“Last night our community witnessed – and many of our residents experienced – physical violence and intimidation by counter protesters…. Peaceful protest was the goal of the protesters who gathered…. In recent weeks on Tuesday evenings, protesters have assembled at City Hall…. I’ve stepped into the crowd to listen when I can…. I condemn those who showed up in our community under the guise of ‘protection’ and instead intimidated, shouted epithets and white nationalist slogans, and in some cases physically assaulted protesters. There is no room for this in our city. There is no room for this in our democratic society that enshrines the right to protest peacefully, dialogue constructively, and come together to build a stronger and more just community.” –Mayor Lauren McLean Statement, July 1, 2020[7]

ILLUSTRATION | Charleston, SC

Use of multiple methods to reach through the information fog with influential messengers.

After the 2015 murders of a prominent Black minister and eight other Black members of a Bible study group, major local, state, and national officials immediately issued statements of grief that reflected their understanding of how the tragedy also raised concerns about racism that needed to be addressed, but they also organized a televised memorial service where the President of the United States spoke. In a televised interview, U.S. Representative James Clyburn, a well-known civil rights figure, noted the diversity of the congregation for the service and attributed it to a community coming together, a positive indication for the nation as it addressed issues of racism in the future.[8] Soon after, the state legislature voted to remove the Confederate flag from the state capitol, taking a clear step in response to the deeper concerns that had been identified.

ILLUSTRATION | A western community

Tailoring for each group the messages, messengers, and means of transmission.

Based on the assessment that followed the community’s immediate adverse response to the reported incident of police officers hitting and pushing a hand-cuffed Black teenager, discussed previously (Part A of this chapter), community members, assisted by CRS conciliators, arranged for and conducted such activities as: issuing a weekly talking point for worship services drafted by the local ministerial alliance; developing a place of worship marquee sign statement, “Peace after Verdict,” to be posted during the police officers’ criminal trial; arranging for panel discussions in schools and on a Black-owned radio station in which panelists explained the law and procedures under which police operated; and having pamphlets distributed by gang members that both explained the situation and urged peaceful reactions.

Interest and attention regarding the criminal trial of the police officers was intense. Significantly, the court agreed that the announcement about a verdict would be staged, so those responsible for the safety of others, such as the schools and law enforcement, would be alerted in time to act before a public announcement triggered protests. As the jury deliberated, city communications staff let the media know about the intriguing story of gangs working together to urge peace. That, rather than the community tensions, became the focus of many post-verdict stories.

ILLUSTRATION | A community with a large state university

Offering alternative ways to communicate a viewpoint in advance of a mass crowd event.

Anticipating that an invitation for a speech by an outside speaker from a racist hate group to its university campus would prompt significant counter-demonstrations, and possible violence, city and university officials, along with student leaders, utilized a wide range of communication networks to urge students and others to attend university-planned events that would occur at the same time as the outside speaker’s presentation, thus offering them a way to avoid giving more publicity to the speaker’s hateful rhetoric.

- Community Relations Service, Find Your Local CRS Office, https://www.justice.gov/crs/locations. ↵

- The National Association for Community Mediation (NAFCM) is a hub for identifying community mediation centers. NAFCM, “Locate a Member,” https://www.nafcm.org/search/advanced.asp. ↵

- For example, the Divided Community Project at The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law offers impartial conciliators; Divided Community Project, “The Bridge Initiative at Moritz,” https://go.osu.edu/dcp. ↵

- See Divided Community Project. Tools for Building Trust: Designing Law Enforcement–Community Dialogue and Reacting to the Use of Deadly Force and Other Critical Law Enforcement Actions 6 (Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2024), https://kb.osu.edu/handle/1811/106216. ↵

- The illustration is included with permission from Brown University News from Brown; Palestinian, Arab, Jewish and Israeli Students at Brown Convene Vigil to Mourn Lives Impacted (Oct. 19, 2023); Sam Levine, New Multicultural Student Group Holds Candlelit Vigil for Palestinian, Israeli Deaths, Brown Daily Herald (Oct. 18, 2023). ↵

- Laura Dugan & Erica Chenowith, Threat, Emboldenment, or Both? The Effects of Political Power on Violent Hate Crimes, 58 Criminology 714 (2020); Karsten Müller & Carlo Schwarz, From Hashtag to Hate Crime: Twitter and Anti-Minority Sentiment (2020), https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/app.20210211 (both finding an association between statements attacking a group and violence against that group). ↵

- City of Boise, Mayor Lauren McLean Statement on July 1 Protest at City Hall (2020). ↵

- Divided Community Project, Key Considerations for Leaders Facing Community Unrest: Effective Problem-Solving Strategies That Have Been Used in Other Communities 22 (2nd ed. 2019), https://kb.osu.edu/handle/1811/106213. ↵