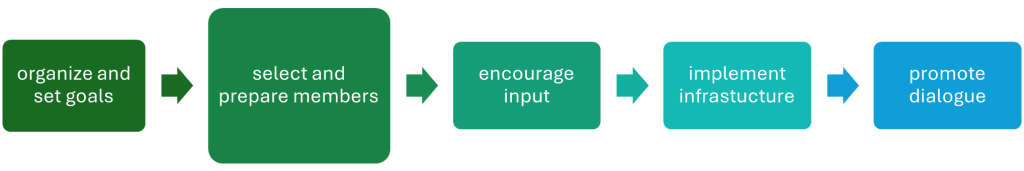

2. Select Participants for the Planning Committee, Persuade Them to Become Involved, and Prepare Them.

The success of a planning initiative depends heavily on the thoughtful selection, engagement, and preparation of its chair and members. While these choices don’t guarantee success, neglecting them slows and complicates the process and may lead to failure. Public support for the planning outcomes will hinge on whether residents feel their perspectives were represented, whether they trust the judgment of the group, and whether the group modeled respectful, constructive dialogue.

Because planning committee members will reflect a wide range of experiences and concerns, it may be challenging for them to demonstrate the kind of collaborative interaction that builds public trust. That’s why it’s essential to engage individuals who have shown they can work effectively across differences—and to appoint a capable, respected leader as chair. Early opportunities for participants to get to know one another and understand their roles can also foster trust and cohesion.

Why Take This Step?

Selecting and preparing the right participants is pivotal. Decisions that affect the community benefit from input across multiple constituencies. Experienced and respected leaders may not volunteer without being invited into a credible process, and their involvement can lend legitimacy and momentum.

Research on procedural justice shows that people are more likely to support decisions—even those they disagree with—when they feel meaningfully involved in the process.[1] Moreover, those who help shape the process are more likely to support its implementation.

While it may seem democratic to announce a committee, solicit self-nominations, and allow members to elect a chair at the first meeting, our experience analyzing planning initiatives suggests that this method rarely yields positive results. A more intentional approach to selection and leadership tends to foster stronger outcomes.

How to take this step

It may be challenging for the members of the organizing group to engage public officials and busy community leaders to establish and participate in a planning committee to address conflict within the community while concurrently planning in advance for community unrest. Personal invitations will help. Other potentially helpful ideas include: pointing out how each plays an important and unique role, emphasizing what a difference the planning may make, and extending personal invitations to leaders that need to be persuaded to join.

All recruiting need not be achieved at once. There may be successive stages at which more representatives of constituencies with different viewpoints, expertise, and lived experiences are brought into the process. Youth group participation, for example, may become critically important (and even seen as uniquely legitimate and mandatory), when there have been conflicts in the schools. You might assign a member to be responsible for adding new members to the planning committee as the process moves forward.

Preparation for members might include lessons from other communities engaged in planning, such as:

- The community will need to adapt the planning process to address its distinctive challenges, but it can benefit from the processes and lessons learned by other communities that have experienced community unrest.

- Disagreement and debate are predictable, desirable features of democratic societies, but community polarization in which persons demonize others is not.

- Planning to resolve divisive issues is neither a strategy to avoid addressing conflicts nor a suggestion that efforts will not be contentious; rather, it is supportive of focusing attention proactively on issues that matter.

- When unrest does occur, if the planning committee has developed a set of communication protocols guiding various parts of government and law enforcement about who does what – and, where appropriate, keeping community leaders informed – community stability can be reinforced, and helps to build trust.

- Most people want to live in a community in which collaborative problem-solving occurs before tensions erupt and polarizations develop.

For these members to act as a group and to remain engaged, establishing relationships and gaining insights and understandings regarding one another’s tasks and experiences can be built incrementally through multiple types of gatherings and encounters. These gatherings might include activities such as law enforcement ride-alongs; community “speak-outs” to public officials from law enforcement, housing, or economic development; and community festival celebrations. The Brookhaven, Georgia planning committee, referenced in Chapter 1, held periodic book discussions. Public meeting laws in some states may require these preliminary meetings to be open to the public. Sometimes, though, attorneys may advise that learning or social activities can be exempt, particularly if non-members are also included.

Planning committee participation in a “table-top exercise” that simulates a crisis situation[2] can support initial planning committee member interactions, trust-building, and confidence in their being comparable in ability to participate effectively in the planning sessions. Participating in such an activity can be time focused –- so it can be conducted to fit multiple persons’ daily work/life schedules; reflective of a realistic situation with which all participants can identify, thereby reinforcing the seriousness and value of the planning effort; and supportive of strengthening group cohesion (and, if participants occupy other roles, developing empathy for those member’s roles).

CHECKLIST: Engaging Planning Committee Participants

- Select and recruit initial participants, who have the personal characteristics and who:

- understand and are respected by each part of the community, so that the result will reflect the aspirations and concerns of the community as a whole,

- serve as bridgebuilders in the community (faith leaders, etc.),

- convey the importance of the planning initiative (perhaps the vice mayor, bar association president, etc.),

- have needed expertise,

- will help to implement plans,

- are well-connected, so that they can engage others in the work, will bring credibility, and have ability to implement, and

- are able and experienced in working personably and collaboratively to resolve differences, so that their work, accomplished within the public view, does not deadlock and gains community respect.

- Select the chair, thereby assuring it is someone with leadership capabilities and avoiding an awkward first meeting at which people who do not know each other are forced to vote and perhaps oppose or offend each other at the start.

- Persuade each selected individual to participate, characterizing the time that will be required, the importance of the goal, and their special role in achieving it.

- Provide a method for adding members as new needs arise.

- Prepare the chair and members, supported by staff and resources to facilitate briefing on their roles, legal limitations, who will make decisions regarding any recommendations, and the opportunity to get to know and understand each other.

ILLUSTRATION | Bloomington, Indiana[3]

Forming a city-community planning committee, listening, forming special planning task forces, establishing an ongoing pattern for learning about and dealing with concerns.

The impetus: In 2019, Bloomington residents learned that one of the produce booths at the popular city Farmers’ Market was operated by individuals with connections to an organization promoting white nationalism. Public meetings were held to discuss the matter. Some demanded that values of inclusion and safety warranted banning the vendor in question. The mayor determined though that the city could not, consistent with the First Amendment, dismiss vendors based solely on their personal beliefs. A group named itself, “No Space for Hate,” and called for more protests at the market. The controversy became so volatile that the mayor closed the 45-year-old market for a two-week period, securing time for reflection and planning by all; when it re-opened, things were calmer, with the city having modified some street closures, added some security cameras, and increased its police presence in order to enhance safety for all participants. The meeting between the “No Space for Hate” leaders and city leaders had made clear to the mayor and others that the issues dividing the community were broader than those related to the market. Learning about the Divided Community Project’s three-day academy program, the city formed a planning team to attend.

Forming the planning team: The team for the academy was a group of knowledgeable and well-connected individuals from both government and the community. It included: the city’s community and family resources director, public engagement director, and police chief; Indiana University – Bloomington’s political and civic engagement program director, interim assistant dean of the education school, and assistant director of diversity initiatives for the business school; and a local artist, an activist, and a businessman. These were busy people, but the recent events in Bloomington and unrest in other cities made clear the importance of their charge. During their three days at the academy, they participated in a tabletop simulation of an unrest situation and learned from civil rights mediators and dispute resolution experts. They left comfortable working together and with a common set of concepts for involving both the city and the community in planning.

Doing the work: The planning team began meeting once or twice a month. They became a sounding board for city leaders when issues arose. As they learned of concerns in the community, they raised them with the rest of the group and consulted with leaders about them. For instance, during the pandemic, unhoused residents put up tents in parks because of potential contagion in the homeless shelter. The park officials took down the tents. After the planning team consulted with other city officials, the city was able to create an isolation area in a hotel for some and began coordinating meetings among shelter providers, health and hospital officials, and police to deal with pandemic issues and the unhoused.

“There are several features of the core team that made them effective. The team is a group of well-connected individuals representing the university, the city, and community voices, who are committed to improving community cohesion. Additionally, team members have made themselves available for consultation with community leaders, often on short notice.” – study of the Bloomington planning process.[4]

Helping community members understand each other: Concerns about racial inclusion that had been brought to the forefront by the farmer’s market issues were broader, though not all of the residents understood that. Working with the Divided Community Project, the mayor brought a former three-term mayor and former Urban League president from another city to listen to community members on these issues and summarize them in a public document. That report described and explained residents’ concerns related to the Farmers’ Market issues, including fears about safety, feelings of loss regarding a traditional meeting place, and more, but also that there were far weightier concerns within the community about housing, representation in public affairs, and policing.[5]

Creating task forces on particular topics: The planning group helped the city to create two task forces. The first related to opportunities for equal opportunity and the city’s policies, procedures, and practices. At the recommendation of that task force, another task force was created to examine the type of policing that would best serve the city and its residents. The city has released plans related to each task force’s work.[6]

- See, e.g., Rebecca Hollander-Blumoff & Tom R. Tyler, Procedural Justice in Negotiation: Procedural Fairness, Outcome Acceptance, and Integrative Potential, 33 Law & Social Inquiry 474, 477-78 (2008). ↵

- See Divided Community Project, Tools for Building Trust: Designing Law Enforcement–Community Dialogue and Reacting to the Use of Deadly Force and other Critical Law Enforcement Actions 38 (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2024), https://go.osu.edu/dcpbuildtrust. ↵

- See e.g., Sooyeon Kang & William Froehlich, Divided Community Project Academy Initiative Case Study #2: Bloomington, IN (2021). ↵

- Sooyeon Kang & William Froehlich, Divided Community Project Academy Initiative Report #2: Bloomington, IN 6 (2021). ↵

- Sooyeon Kang & William Froehlich, Divided Community Project Academy Initiative Report #2: Bloomington, IN (2021). ↵

- City of Bloomington, Plan to Advance Racial Equity ( https://bloomington.in.gov/sites/default/files/2020-10/Plan%20to%20Advance%20Racial%20Equity%20v.2.pdf; City of Bloomington, Future of Policing Task Force Initial Report (2022), https://bloomington.in.gov/sites/default/files/2022-05/Future%20of%20Policing%20Task%20Force%20Initial%20Report%20052022.docx.pdf. ↵