1. Organize a Planning Process for Contributing to the Resiliency of the Community.

Communities often begin planning in response to a specific catalyst — such as issues raised by anticipated population growth, debates over statues or monuments,[1] efforts to improve mass transit, or concern about local reactions to international or national conflicts. Sometimes, the motivation is broader: a desire to enhance residents’ quality of life and prepare for future challenges. Whatever the immediate focus, one can expect that a thoughtfully organized planning initiative will also contribute positively to the community’s resiliency.

Why Take This Step?

Resilient communities are built on collaboration, meaningful engagement, and broad cooperation. These interwoven relationships help communities address problems constructively and often prevent unrest. Proactive planning can also reduce the significant costs associated with inadequate responses to conflict — both tangible (e.g., property damage, injuries, arrests, canceled events, overtime expenses) and intangible (e.g., distrust, lasting bitterness, harm to community identity).

Developing a plan is most effective when it’s a shared responsibility. Public officials can initiate the process by allocating personnel and resources, then convening leaders from across the community. Official support lends credibility and signals a commitment to implementation, encouraging busy community leaders to participate meaningfully.

Still, if collaborative initiatives to develop a plan are not launched by public officials, non-governmental civil society organizations and community leaders have sometimes seized the initiative to suggest to officials that such a process is warranted and to advocate for its broad-based design. In fact, initiation by a community entity – e.g. the local chamber of commerce, bar association, or civil rights organization — might encourage broader participation from those who might be worried that the public officials have political motives for initiating the planning.

The planning and implementation may require public funding. To assist public officials in the cost-benefit analysis, it helps if organizers assess the costs of the initiative as well as the likely costs if the initiative is not undertaken (the fifth bullet below).

How to take this step

The first of the steps covered by this guide is planning to plan. Public officials can establish a small organizing group whose task is to design an initial process for engaging multiple stakeholders to constitute the planning committee that would thereafter develop an action plan. This involves assessing the issues that the community faces and setting the goals for the initiative, as a background to selecting, recruiting, preparing, and providing resources for the Planning Committee, as detailed in this checklist.

CHECKLIST: Organizing a Planning Process

- Adopt principles to shape the organizing effort that foster stability between leading public officials and community members that include:

- Transparency,

- Accountability,

- Open communications with all constituents,

- Public visibility.

- Set overall goals, such as methods to assess and respond to community concerns and prepare for major conflicts.

- Develop a planning checklist that, among other things, identifies:

- Community groups and interests that could be included in the process,

- Municipal agencies that may have expertise that is not generally included in community planning activities,

- Community resources whose support can be engaged to support the planning,

- Research to conduct.

- Attempt to frame (i.e. name) the effort in a positive manner, which is accurate and inviting.

- Assess what might occur if no planning takes place, by examining history of past community unrest; the costs, including human ones, of community unrest experienced in comparable communities across the nation; and recent local changes that have had negative impacts for religious, racial, ethnic, or other groups in contexts such as school safety, unemployment, health services, or law enforcement practices.

- Evaluate the community’s ability to strengthen its resiliency. For example, examine its past effectiveness in dealing with division, whether decision-makers have a variety of lived experiences that represent the community broadly, the existing public agency processes and informal practices to address long-term, sustained divisions, and perspectives of key spokespersons for varied community interests regarding the overall health of the community. The National Civic League offers a useful assessment tool, the Civic Index, for this evaluation.[2]

- Determine whether community leaders from multiple sectors — business, civil rights, faith, foundation, nonprofit and neighborhood associations — have adequate communication channels with public officials and with one another during times of both tranquility and unrest.

- Make initial determinations regarding categories of planning participants, including:

- Local public officials and their staff to whom the work will be delegated,

- Law enforcement officials,

- Emergency management staff,

- Community leaders, including persons from the neighborhoods, faith, bar association, business, education, youth organizations, and “local celebrity” (tv/radio hosts, athletes, etc.).

ILLUSTRATION | Brookhaven, GA

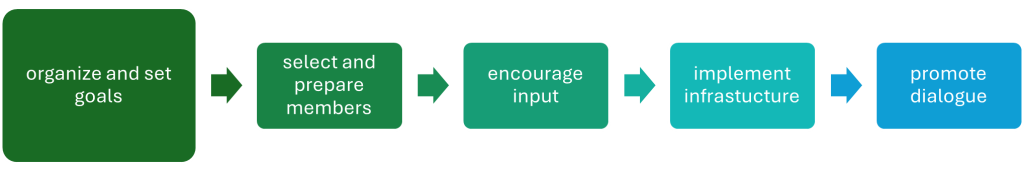

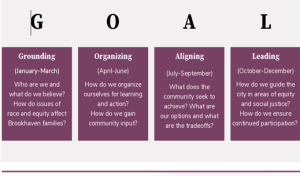

In 2021, city leaders in Brookhaven, Georgia sought help to examine and pursue greater fairness across races in their community. They contracted with a nonprofit facilitator, the Chrysalis Lab, and arranged for consulting from the Kettering Foundation to advise them as they began. The consultants, listening to the planners, developed the following visual of goals and plans that could be used to reassure the community about how it would move forward.

The organizers’ work paid off once the planning committee – called the “commission” — was organized and continued to work with consultants to prioritize both a schedule and listening that was closely tied to the goals. The commission was then in a solid position to implement the steps outlined in the next few chapters.[3]

The commission also developed and implemented a path for encouraging interactions with and among residents and city officials. By the end of 2021, the Commission made recommendations to the Brookhaven City Council, a number of which have been adopted.

By 2024, a commission-recommended survey of city residents indicated considerable satisfaction with progress in terms of relationships among residents and with the police, and optimism about the future.[4]

- For a guide specifically for this issue, see Divided Community Project and Mershon Center for International Securities Studies, Symbols and Public Spaces amid Division: Practical Ideas for Community and University Leaders (2nd ed. 2025). ↵

- National Civic League, Civic Index - 4th Edition, https://www.nationalcivicleague.org/resources/civicindex/. ↵

- The illustrations come from the commission’s final report, Building Community. Kindling Hope. Seeding Change. Social Justice, Race & Equity Commission Recommendations (Presented to the Brookhaven City Council, December 14, 2021), https://www.brookhavenga.gov/media/14701. ↵

- 2024 City of Brookhaven Diversity, Equity, Inclusion & Belonging Survey Presented by Etc. Institute, June 2024. ↵