8. Plan with Law Enforcement and Community Leaders for Potential Unrest Scenarios

While most demonstrations are peaceful and do not result in arrests, mass crowd events carry the risk of serious incidents, even tragedy. Reports following the latter often recommend better planning in advance of unrest.[1] Ideally, planning should be extensive, but even a brief meeting—such as a two-hour session on the eve of a protest—can significantly improve leadership response.

While most demonstrations are peaceful and do not result in arrests, mass crowd events carry the risk of serious incidents, even tragedy. Reports following the latter often recommend better planning in advance of unrest.[1] Ideally, planning should be extensive, but even a brief meeting—such as a two-hour session on the eve of a protest—can significantly improve leadership response.

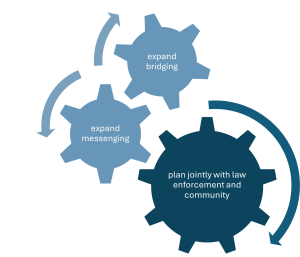

This chapter draws on lessons from these reports to offer guidance for planning across a range of conflict scenarios. It also recommends establishing an Emergency Operations Center to adapt plans in real time as unrest unfolds. It emphasizes the benefits of joint planning by law enforcement (all agencies that might be involved in a worst-case scenario, such as city, campus, county, and state police and, more recently, military that might be sent by state or federal officials), city officials, leaders of any colleges or universities that might become protest sites, and community leaders.

Why take this step?

Community unrest shares a critical feature with natural disasters like hurricanes and wildfires: lives can be saved and damage minimized through rapid, coordinated action. Planning ahead enables leaders to respond wisely and swiftly.

In an independent “after-action” report of the tragic 2017 Charlottesville “Unite the Right” demonstrations, the first conclusion was: “Better preparation is critical.”[2]

With time to prepare, planning groups can develop tailored checklists for various scenarios—such as counter-protester arrivals, hunger strikes, or encampments. These checklists help ensure readiness and reduce confusion during high-pressure moments.

Preparation also provides time to develop communication checklists tailored to specific scenarios (see Chapter 7). These tools help leaders stay in touch—quickly and constructively—with residents, demonstrators, officials, and the media during crisis moments.

The planning process also makes it possible to incorporate ideas from community leaders, who can then explain and defend the rationale when plans are implemented during unrest. Planning enables those who will participate in the decision-making during protests to be designated in advance, receive training, and practice possible responses through tabletop simulations. It also makes it feasible to brief all officers on plans before they arrive to work at the demonstration site.

Another important outcome of proactive planning is building familiarity, relationships, and trust that speeds coordinated responses by and between siloed leaders, agencies and communities.

Recent changes underscore the benefits of taking into account:

- Joint planning: Even more now, it will help to include all relevant law enforcement agencies (city, campus, county, state police, and potentially federal law enforcement and military troops), city officials, university leaders, and community representatives.

- Campus-specific strategies: Protests often begin on or spread to college campuses, where dynamics differ. City police may not be familiar with students, who may not anticipate consequences. Campus administrators may need guidance on planning, rapid decision-making, and coordination with law enforcement.

- Changing protest dynamics: Current protests more often:

- Address national or international issues,

- Last multiple days,

- Attract counter-protests quickly via social media,

- Lack formal leadership, though influential individuals may emerge.

- Need for coordination: Planning and timely response has become more critical because of greater likelihood that:

- A governor deploys the state patrol or National Guard

- Federal military personnel arrive without a local or state request

- Note that the military may have different rules of engagement (including arrest and confrontation policies). In addition, upon the arrival of military troops, surprised demonstrators might escalate tactics, especially if they perceive the troops to be treating them as an enemy in battle. Working ahead allows exploration of the feasibility of including representatives of state and federal troops and law enforcement in the planning and even in the Emergency Operations Center during a mass crowd event.

- A campus within the community becomes a site of protest and campus safety forces become involved. As one university police chief pointed out:

“Campus public safety partnerships with area law enforcement, students, campus leadership, neighboring communities and the business sector are essential for effective preparedness and response to large-scale protests and hate incidents. No public safety department has unlimited resources for most large-scaled incidents and the need for effective partnerships regarding intelligence, training, and resource sharing is essential for all communities. Effective communication and cooperation between public safety stakeholders during the training and planning process serves to build trust and coordination of resources before, during and after a critical incident or crisis.” – Daryl Green, Associate Vice President for Public Safety and Chief of Police University Alabama Birmingham Police and Public Safety

How to take this step

Joint planning involving all pertinent law enforcement agencies and other public officials, even if held only a few hours before an expected event, can:

A. identify possible responses to particular scenarios.

B. clarify and address organizational issues (e.g., who should be involved, how prepared).

If there is time, the agenda might be broadened:

C. conduct contingent planning for likely scenarios.

A rough agenda for a joint city administration and law enforcement meeting might include discussion of how each task below will be done.

The agenda items listed in A, B, and C overlap to accommodate quick reference.

A. How will each of the following actions be conducted and who has responsibility for them?

Release communications for residents and protestors that set a positive tone for any demonstrations and explain what is permitted and prohibited in this context.

Contact representatives of the groups likely to engage in a protest[3] to:

- Set a positive tone about their expressing their views and ask about:

- The anticipated number and characteristics (children or elderly involved? victim/family members? leaders?) of protestors to aid with safety and accessibility.

- Anticipated counter demonstrations and whether counter demonstrators will embed themselves in the crowd.

- Expected participant emotions, including those with respect to law enforcement.

- Helpful actions to keep participants safe.

- Their plans to support participants (water, first aid, transportation, etc.).

- Means to communicate with participants if dangers arise, such as from counter protesters.

- Let these representatives know about:

- Safety, medical, and emotional support resources that the city will provide.

- Suggestions about safety for participants, including routes to/from protests.

- Ways to contact police.

Augment, as warranted – even contracting with outside groups — advisors, mediators, law enforcement/dialogue team, and communications assistance.

Contact the media with suggestions for safe sites for their work and ways to stay in touch.[4]

Organize alternative ways for those seeking a safer way to express views than a mass crowd event (see Chapter 7).

Jointly discuss what more can be done to reduce the chances of violence during the demonstrations, such as de-escalation trained police, marshals, ambassadors, alternate events, and more, by reviewing the ideas listed under the Emergency Operations Center, below. In the case of a controversial speaker, can the event be moved inside where a shooter might be easier to stop?

Jointly draft “incident action plans establishing the criteria for arrests, use of chemical irritants, rubber bullets, or other forcible actions (“rules of engagement”). Include instructions for officers to intervene to prevent fellow officers from using force in violation of the protocol.[5] Designate who makes arrest or forcible actions in various contexts (on a campus, in the city, on state or federal property, etc.).

Determine the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) participants who will coordinate and make decisions as the mass crowd event unfolds and make sure that all involved will use the same official emergency channels to communicate. To increase the information available and quick decision-making, it will be important to include the mayor, communications staff, law director/prosecuting attorney, emergency medical and fire personnel, representatives of every law enforcement agency that might be involved in worst case scenarios, and perhaps a civil rights mediator and neighborhood outreach staff. Both campus administrators and campus police might be asked to join the Center if the protest might ultimately move to campus or attract a substantial number of students. Designate back-up personnel for each EOC role by allowing rotation of shifts if protests last for multiple days.

In addition, assign responsibilities for:

- Communications with participants and with the public.

- Watching for known antagonists and others bent on violence or destruction and developing a strategy to respond to them while protecting the safety of those demonstrating peacefully.

- Assessing the goals and intensity of emotions of each part of the crowd and communicating with the EOC, especially watching for counter protesters and developing plans to separate them.

- Observing the routes people are taking coming to and, especially, leaving the event to be certain they have needed transportation, protection, and information on how to do so safely.

- Directing passing motorists and pedestrians to keep them safe and keep demonstrators safe from them.

- Providing medical, sanitation, and counseling resources.

Train EOC participants and practice plans with a tabletop simulation or at least talk through what will be done in a variety of scenarios, if time permits.[6]

Brief officers who will be working at the demonstration site (including on arrest protocols),[7] as well as municipal department leaders.[8]

Consider committing to contract for an after- action report to help inform the city leaders’ management of future mass crowd events.[9]

B. How will the following potential tasks be allocated and accomplished in the Emergency Operations Center?

Communicate frequently and through a variety of messengers/media with the public and demonstrators to explain procedures and limitations while speaking with respect for demonstrators as fellow community members, support for their freedom to express their viewpoints, and an interest in protecting safety.

Attempt to stay in touch with those participating in the crowd:

- Use the contacts with demonstrators that you acquired ahead of time.

- Communicate through neutral sources if protest leaders do not trust and therefore are not willing to stay in touch directly with city officials; protest leaders might view mediators or trusted civic organizations as reliable sources and allow them to act as intermediaries in communications.

- Assign responsibility to watch and assess public social media sources during the demonstration to convey to the group the mood and concerns that are circulating.

- Suggest to demonstrators ways to remain safe, such as changing location to avoid counter demonstrators or safe routes to their cars when leaving the demonstration.

To reduce the risks of trouble:

- Stay in touch with any community members acting as parade marshals,[10] working on the perimeter of the demonstration, and any trained de-escalators, either from the community or police, or faith leaders, who are working in the crowd.[11]

- Tell nearby residents or pedestrians how to avoid unsafe situations.

- Consider whether law enforcement should be in view of demonstrators and, if in view, presented in non-threatening ways (baseball caps, no riot gear, etc.).

- Prepare designated protest or event space to make it safer (removing trash cans that might be set on fire, having security cameras in place, guarding potential target areas such as places of worship or federal properties, etc.).

- Separate demonstrators from counter demonstrators, placing officers so that they do not appear to favor one group over the other, such as having every other officer face a different group, remembering that the presence of opposing protestors increases the risks of violence.

- Consider the rules of engagement, including whether officers should be instructed not to arrest for minor offenses that do not threaten safety and what other non-lethal methods might be employed to move members of the crowd.

- Monitor stress levels of officers and offer replacements and peer support.[12]

- Watch for a need to position firefighting and medical emergency resources at particular locations.

- Provide guarded paths for demonstrators returning to their cars, as this may be a more dangerous moment for them than the demonstration itself.

“Recognize always that the extent to which the cooperation of the public can be secured diminishes proportionately the necessity of the use of physical force and compulsion for achieving police objectives. Use physical force only when the exercise of persuasion, advice and warning is found to be insufficient to obtain public cooperation to an extent necessary to secure observance of law or to restore order, and to use only the minimum degree of physical force which is necessary on any particular occasion for achieving a police objective.” – Sir Robert Peel, 1829, Principles 4 and 6 from his statement of the proposed nine principles for governing the conduct of England’s first police force.[13]

- Observe various parts of the crowd and individuals within the crowd to determine if any members threaten the safety of others or are moving to destroy property. Advise those on the ground to whenever feasible, arrest or move against only the individuals offending, who may have tried to hide among peaceful demonstrators. When officers might take substantial risks by entering the crowd to arrest particular individuals, there might be plans to station officers in protective gear nearby, but out of sight, to use when that is only safe way.

“[B]y treating entire crowds as dangerous and indiscriminately denying participants the opportunity to express themselves, police can inadvertently lead moderate members of a crowd to align with more radical members against the police. A better approach is for police to focus enforcement actions on only those whose violent, destructive, or otherwise illegal conduct requires immediate attention. In a protest setting, the police should make it clear that they are continuing to facilitate the rights of other participants to continue expressing their views as long as they behave in a peaceful and law-abiding manner.”[14] – Reporting on research generally and a review of the “Occupy Movement” and Ferguson, Missouri demonstrations.

C. If there is more time, scenario-specific planning ahead can build on the foundation of the organizational planning and include decisions on who will handle each of the following matters in each potential scenario.

Planning for some of the items above in each foreseeable scenario will help react more quickly and effectively. Topics that warrant deeper and more specific preparation include:

- What are potential likely scenarios in the months ahead and how is each likely to unfold? Creation of and periodic meetings with a subset of the Emergency Operations Center might focus on what is occurring elsewhere, stirring locally, or key events such as anniversaries of an invasion or the jury verdict related to a police use of force. Planners might review approaches that have been used locally by the affected groups, whether counter protests are likely, and what experts such as the U.S. Department of Justice Community Relations Service have learned about protests in other communities and any new approaches to keeping demonstrators and the community safe.[15]

- Should marshals and/or de-escalation teams be trained and employed? Both the U.S. Department of Justice Community Relations Service and Princeton University’s Bridging Divides Initiative offer information on this training.[16] The option of receiving training and serving as a parade marshal might be attractive to those who want to help to keep members of the crowd safe.

- Who can arrange to have experts who can assess the crowd during the protest? Such an expert can communicate with the EOC about the intensity of emotions and identify those who threaten safety of others or who might become victims of violence. Sometimes separation or arrests of a few disruptive or violent individuals can keep the rest of the crowd peaceful and safe.[17]

- What can be done to keep law enforcement presence from escalating tensions and violence? Optional decisions might include, for example, not to wear riot gear, to situate parade marshals between the crowd and law enforcement,[18] to ride bicycles rather than horses or motorcycles, to divert the group if it heads toward military groups, and to find non-threatening ways to separate protests and counter-protests. (Because of risks to law enforcement if officers must go through a crowd to arrest a violent individual, officers in riot gear might be located out of sight, but nearby.)

- Who will support those involved in ensuring safety during the unrest? Law enforcement may need frequent substitutions and encouragement during a high stress situation.

- Who will issue statements to the public and public officials about what is occurring during the demonstration and then, afterwards, what occurred? Will it send the best message if all communications come from law enforcement alone as opposed to jointly with the mayor? What other community leaders or influencers might be willing to issue statements or join city leaders making the statements to amplify the message to their constituents or followers? Who will stay in touch with other officials, such as the governor, district representatives, or federal officials who might be contacted by the media for comments on what is unfolding during demonstrations?

- How will the Incident Management Team that will operate on the ground practice its plans? An hour or two of practice through a tabletop simulation and facilitated discussion afterward can confirm the workability of some plans and identify what additional plans or training should be in place.

- Who should be consulted during the planning process? Engaging community leaders (e.g., faith leaders, civil rights leaders, business leaders, bar association leaders) and considering their ideas for planning may provide valuable perspectives. In addition, it may help these community leaders understand what will be done and why, so that they will be willing to explain to their constituencies what to expect beforehand and explain the actions afterward. (There may be some security measures that should remain confidential and therefore discussed among decision-makers only.

- Who can develop a range of safe options for residents to publicize their views? These might include encouraging faith leaders and other community groups to hold events throughout the community, perhaps at a common time, with media coverage welcomed; encouraging small gatherings that together achieve the same effect as a single large gathering; talk with protest organizers about selecting sites that are not federal in nature and therefore less likely to result in the arrival of federal military; and work with various media (social media, radio, newspapers) that would welcome expression of viewpoints by groups or individuals and let residents know about the opportunities. Can they be encouraged to hold controversial speakers inside where the speaker’s safety can be better protected?

- Who should be on a task force to prepare ahead if a hunger strike occurs? Consider including people who can deal with the health, psychological, and comfort needs of strikers and the emotional needs of those who observe the strikers’ suffering, plus communications staff, mediators, and decision-makers. The task force can become familiar with the medical and psychological effects of hunger strikes at various stages and have a team ready to respond within hours. When a strike occurs, they can be ready to assess:

- Who is the audience for the strike? (e.g., Is it to influence those who want to stop their suffering? Is it to embarrass leaders? Is it to gain publicity for a cause?)

- What is the ask (not just the public demands, but also the interests underlying them)?

- Who decides for the strikers, including any external members who are not fasting and therefore may be in a better position to decide?

- Who will stay in touch with strikers and their representatives regarding their needs and safety?

- Who will be trusted by strikers or their representatives to stay in conversation about ways to resolve the strike?

- Who will prepare communications to those troubled about the strikers’ well-being?

- Who should be on a planning group to prepare for reactions to immigration enforcement actions? Community resistance to the recent increased ICE enforcement has become robust and organized. Vigilantes seeking to enforce immigration laws and individuals impersonating federal agents have added to an atmosphere of fear, anger and distrust — including distrust of local law enforcement.[19] As people do not react as rationally when emotions are raw, it may help for the planning group to include lawyers, law enforcement representatives, communications specialists, and community representatives. Such a group can teach the community about what the law permits and publicize safe ways for residents to express themselves and support each other.

- What training would be helpful for EOC participants? The planning group can anticipate and train regarding what EOC participants would need to know to participate in the moment.[20] Communications staff, for example, may be unaware of what information should remain confidential. Law enforcement may not be aware of all communications approaches available to reach demonstrators or those who might join them.

ILLUSTRATION | A southern community

Joint planning among four levels of government officials, a university, six law enforcement agencies, the Community Relations Service, and selected community leaders.

A local group announced that they would host a speaker on the campus of a large state university within this medium-sized city. The speaker’s views and past speeches had sparked protests and counter protests elsewhere. The university initially resisted and decided that it was required to permit the speech. The delay created a brief opportunity to plan ahead.

Given what had occurred elsewhere at this speaker’s events, and the large number of students on this particular campus, law enforcement from the campus, city, county, state, National Guard, and FBI might be engaged in responding to the protests. Administrators, legal counsel, communications, intelligence, fire and medical, at the campus, city, county, and state levels would be involved as well. All would need advice and help from other community and campus leaders, including students. The campus police chief convened these persons, assisted by Thomas Battles, then-regional director of the US Department of Justice Community Relations Service.

The planned Emergency Operations Center contained video and secure communications abilities. On the day of the speech, a chair for the leader of each these multiple agencies and stakeholders would be assigned (with the understanding that the seat might be filled by a representative in touch with the seat holder), including: the university president, mayor, a city commission member (usually the person in whose district the protests would likely occur), the heads of campus, city, county, state, National Guard, and state FBI offices, those responsible for fire and medical assistance at the city, county, and state levels, a representative in touch with intelligence officers at all agencies, a communications officer in touch with another group that included communication staff from all involved agencies, legal counsel for all involved entities, the US Attorney, a Community Relations Service conciliator, and three community leaders who had worked closely with these groups.

This group’s plans included:

Providing attractive alternatives to joining a protest (including student groups and bars hosting parties, marketing the events the week before the speech) and letting students know that they would not be penalized for not attending classes that day, thus reducing the number of students who would otherwise be on campus

Rules of engagement: University leaders told the group that they would not ask law enforcement to arrest or clear students who yelled during the speech. Operational level representatives of the five law enforcement agencies together proposed additional rules of engagement to the larger group, which the group reviewed and approved.

Preparation of site: Already scheduled inside (securing the perimeter for speakers outside may be more difficult), students would be told that they could not bring weapons or signs that were attached to sticks to the “free speech” area of campus near the site of the speech. Seats nearest the speaker would be filled ahead of time, with the front row being filled with associates of the speaker and the second row with plain clothes officers. Intelligence officers and a Community Relations Service conciliator would watch members of the crowd and relay information to the Incident Command Center, where members were also watching the crowd by video. Security for the speaker’s departure from the site would be provided by the law enforcement agency responsible for the jurisdictions transversed until the speaker reached the state border. Police in protective riot gear would be out of sight, near the site.

Counter protests: Recognizing the greater risks of violence when protestors and counter protestors converge, they made plans to separate protestors during the event and as they returned to their cars.

Communications: The university president urged students not to give the speaker the attention he sought and to attend counter-events. Student leaders joined their voices to his message, creating video messages to stay away.

After-action report: All supported having this analysis done by an independent group.

ILLUSTRATIONS | Gainesville, FL & College Station, TX

Using the time before the event to engage the community broadly in preparations.

Groups seeking attention may sponsor a speaker whose past speeches have insulted various identity groups. They may select a city with a large university and a speaking venue on campus, confident that tens of thousands of students will augment local residents in protesting the hate speech targeted at their fellow students and residents. Accompanied by provocateurs, these groups sometimes seek the national spotlight that crowd violence might focus on them. A part of the common strategy is to schedule the speech soon after it is announced, banking on the cities and universities not having a plan to avert violence that it is ready to deploy effectively.

Learning ahead of a divisive event, two campuses used the time to engage students and others in planning alternative events to avert violence and arrests. Photo: iStock.

Finding a way to plan ahead: In two instances, Gainesville, Florida in 2017[21] and College Station, Texas in 2016,[22] the universities (University of Florida and Texas A&M University) were able to delay the event (though they could not prevent it) while negotiating event protocols, and even in one case refusing to make a particular venue available until forced to do so through litigation. The cities and campuses took advantage of the few weeks before the speech to put plans in place that averted violence, resulted in only a few arrests, did not involve the use of officers in riot gear (though these were posted nearby in case needed), and left the communities feeling a sense of common purpose.

Planning logistics jointly: In Gainesville, logistical preparations included preparing the Emergency Operations Center with seats for representatives from: all of the law enforcement agencies that might be engaged in a worst case scenario, including their intelligence units; representatives of fire and emergency medical at all levels; the mayor; the University of Florida president; a communications person representing communications staff members for all of the above units; legal counsel for these units; a U.S. Department of Justice Community Relations Service conciliator; seats for particular public officials (governor, elected district representatives, etc.), and, in one, for several trusted community leaders. They agreed on rules of engagement – no arrests for yelling during the speech, for example. They prepared to separate counter protestors both during the event and afterward as they walked to their dorms or cars. They prepared the site, including perimeter screening for weapons, protection against vehicles, and assuring that officers or supporters of the speaker would be in the front rows for the speech. They assigned mediators and other specialists to watch individuals within the crowd and report to the EOC while the EOC members also watched the crowd through video connections. They monitored traffic into the city and within it, and law enforcement intelligence officers looked for opportunists seeking to incite or commit violence. They provided security escorts for the speaker.

Planning alternatives to protest: At the same time, the presidents of both universities were candid with students about their opposition to hosting the speaker and explained that demonstrating students might increase the event’s profile in the national media – especially if violence occurred — thus unwittingly bringing more attention to the speaker’s cause that they sought to oppose. They told students that the best way to undermine the speaker’s cause was to stay away from the event entirely. Meeting with student leaders, both universities offered a variety of alternative events during the speaking event – a music group, parties at bars, sororities and fraternities, and more. At one university, the president told students that they would not be penalized for missing class that day – that they could stay home. Student leaders on one campus organized a social media site at which hundreds of students posted themselves making a heart shape with their hands and announcing that they would stay away from the hate. A university website told students what they could and could not do if they protested and advised on safety. A music professor at one university played the civil rights anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” on the campus carillon tower during the speech.

No injuries and a positive spirit: It was an expensive effort, but planning ahead worked. Thousands rather than tens of thousands protested the event. No one was hurt. The communications staff and the resulting publicity focused on the united efforts of these communities more than the speaker’s rhetoric.

ILLUSTRATION | St. Louis, MO

Communicating can project positive expectations, respect, support, and interests in safety.

Excerpts from the St. Louis mayor office’s public statement:

“On Wednesday, May 1, 2024, a peaceful protest occurred on the campus of St. Louis University. No arrests were made by the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department. As part of the protest was on city streets, the SLMPD was on hand to direct traffic to ensure the safety of demonstrators, pedestrians, and drivers.

“’I’m proud of St. Louis City,’ said Mayor Tishaura O. Jones. ‘Demonstrators on Wednesday night participated in a peaceful protest, and Chief Tracy and the SLMPD kept our city safe. Peace was met with peace.’

“This was not the first protest on the issue of the Israel-Hamas war to occur in the City of St. Louis, and will likely not be the last. It remains the top priority of Mayor Jones and the City of St. Louis to ensure that all members of the community are safe.

“The administration and the SLMPD are aware of another planned protest for today, Friday, May 3, that will begin in Forest Park….

“We are hopeful that both the protesters and university administration can emulate the precedent set by Wednesday night’s protest. It is our belief that there were two essential factors that helped to ensure the safety of all in the community:

1) The community centered the rejection of violence in their demonstration.

2) St. Louis University’s administration provided clarity to members of the SLU community regarding their expectations for the protest well before the scheduled start time.

“Our city and our region will continue to have difficult conversations about our community and its part in world events. Our hope is to continue to engage one another in a respectful and productive dialogue.”[23]

– Mayor Tishaura O. Jones Administration “Statement on Planned Protest Friday,” released on May 3, 2024

ILLUSTRATIONS | Seattle, WA & Columbus, OH

Police dialogue teams can reduce arrests and facilitate peaceful demonstrations

Trained police dialogue teams in Seattle and Columbus establish rapport with protesters and focus on encouraging peaceful expression. Identified by their brightly colored vests, police on the dialogue teams do not focus on enforcement but instead on de-escalating tension, problem-solving, and bolstering peaceful methods. A social scientist studying their actions found early indications that dialogue teams enhance safety and public trust of police and reduce the widespread arrests that can encompass peaceful protesters as police pursue violent individuals within the demonstration.[24]

ILLUSTRATION | Gainesville, FL

Operating an Emergency Operations Center during the event.

As the time of the potentially divisive campus speech in Gainesville discussed above approached, the state highway patrol and intelligence units from various agencies reported to the EOC on those making their way toward the city. City officers reported on traffic within the city and sought the EOC’s approval to shift traffic resources. Given that the traffic patterns suggested an increased participant presence at the protest site and accompanying safety concerns, the intelligence officers, following the EOC plan, escorted the speaker to a room off the stage at the speaking site, to protect him while crowd developments could be monitored. Both local and EOC members watched the crowds inside and outside, keeping in touch with each other. Once the speaker began, audience members yelled throughout the speech.

Several thousand people demonstrated, with counter protesters separated by officers. The nearby officers in riot gear did not need deployment; they remained out of sight. Law enforcement provided security until the speaker’s car reached the state line, in one instance heading off demonstrators who attempted to follow the speaker’s car. No one was injured, no property was damaged, and only five arrests were made, one for a non-student carrying a gun, one for an individual not following police directions, and three for driving up after the speaker had left and firing a shot toward protestors. The after-action report praised the preparation for the event.[25]

ILLUSTRATION | A western city

Supplementing the EOC with a command post for community representatives.

When the court declared a hung jury in the first criminal trial in which officers were charged with excessive force against a handcuffed Black teenager, sparking concerns about violence both against the police and between Black and Latino gangs, discussed in Chapter 7, community members had gathered in their own command post. It included representatives of the police, gangs, the ministerial alliance, city officials, chamber of commerce representatives, and Hollywood celebrities. Relationships had been building among the group as the result of the assessment process described in Chapter 7. Gang members had been trained as ambassadors and were distributing leaflets about a vigil that evening. Police members helped the gang members find parking as they moved around the city. About 20 media trucks were parked at the courthouse to cover the verdict, but many instead covered the work of this group. The day unfolded without violence, destruction, or arrests.

- See, e.g., Hunton & Williams LLP, Final Report: Independent Review of the 2017 Protest Events in Charlottesville, Virginia 7 (2017), https://www.huntonak.com/images/content/3/4/v4/34613/final-report-adacompliant-ready.pdf.); Neil & Harwell, Report of Independent Counsel Neil & Harwell, PLC to Daniel Diermeier, Chancellor, Vanderbilt University 21 (2024); After-Action Review Committee Report to the Wake Forest University Community 3-4 (2024), https://assets.wfu.edu/sites/84/2024/08/AARC-Report-to-the-Wake-Forest-Community.pdf. ↵

- Hunton & Williams LLP, Final Report: Independent Review of the 2017 Protest Events in Charlottesville, Virginia 7, 172 (2017), https://www.huntonak.com/images/content/3/4/v4/34613/final-report-adacompliant-ready.pdf (The independent report on the 2017 Charlottesville protests noted instances of lack of coordination and poor communication among local, state, and university law enforcement, and concluded, “Without a unified command and true integration of resources, the effectiveness of a multiagency response is severely handicapped.”). Sources for changes in protest activity are: the Task Force for 21st Century Policing and its webinars, https://www.21cpsolutions.com/, and the Bridging Divides Initiative at Princeton University, https://bridgingdivides.princeton.edu/. ↵

- Research conducted during campus “encampment” protests in 2024 indicated that opening “lines of communication early between administration and student protests leaders” tended to result in quicker resolutions and less extreme demands. Matthew J. Mayhew et al., Lessons from Campus Encampments, Columbus Dispatch 4E (Aug. 10, 2025). ↵

- Police Executive Research Forum, Police-Media Interactions During Mass Demonstrations: Practical, Actionable Recommendations 16 (2024), https://portal.cops.usdoj.gov/resourcecenter/content.ashx/cops-r1167-pub.pdf (“Police agencies may want to coordinate with news outlets to designate safe locations for members of the media to cover an event. Reporters still have the right to report from elsewhere if they choose, but they should recognize that this choice might reduce police officers’ ability to keep them safe.”). ↵

- See City of Columbia Police Department, Columbia Strong: Critical Incident Review 2020 (2020) (discussing how to improve “incident action plans”). See Hillard Heintze, Final Report: City of Minneapolis, Protecting What Matters: An After-Action Review of City Agencies’ Responses to Activities Directly Following George Floyd’s Death on May 25, 2020 (2022), https://lims.minneapolismn.gov/Download/RCAV2/26623/2020-Civil-Unrest-After-Action-Review-Report.pdf (discussing the value of Incident Action Plans). ↵

- Hillard Heintze, Final Report: City of Minneapolis, Protecting What Matters: An After-Action Review of City Agencies’ Responses to Activities Directly Following George Floyd’s Death on May 25, 2020 85 (2022), https://lims.minneapolismn.gov/Download/RCAV2/26623/2020-Civil-Unrest-After-Action-Review-Report.pdf. See CNA & Montgomery McCracken, Philadelphia Police Department’s Response to Demonstrations and Civil Unrest May 30-June 15, 2020 24, 81 (2020), https://www.cna.org/archive/CNA_Files/pdf/iaa-2020-u-028506-final.pdf (urging newly elected officials to participate in a tabletop exercise focused on emergency response within 30 days of appointment). ↵

- CNA & Montgomery McCracken, Philadelphia Police Department’s Response to Demonstrations and Civil Unrest May 30-June 15, 2020 14, 45 (2020), https://www.cna.org/archive/CNA_Files/pdf/iaa-2020-u-028506-final.pdf. ↵

- Id. 74, 84. ↵

- National Police Foundation, How to Conduct an After Action Review (2020), https://www.policinginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/How-to-Conduct-an-AAR.pdf. ↵

- Community Relations Service, Event Marshals: Maintaining Safety During Public Events. (last modified September 5, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/crs/our-work/training/event-marshals. ↵

- Gabrielle T. Isaac & Robin S. Engel, Agency Implementation: Applied De-escalation Tactics (2024), https://portal.cops.usdoj.gov/resourcecenter/content.ashx/cops-r1162-pub.pdf. ↵

- City of Cleveland, May 30 After Action Report 38. (2020), https://ewscripps.brightspotcdn.com/42/d8/9b2886474d6294744b57ec11e0b4/cdp-after-action-review-10.pdf (urging the development of a “safety officer and employee assistance unit” during and after an event). ↵

- Sir Robert Peel, 9 Principles of Policing (1829), reported by the Law Enforcement Action Partnership, https://lawenforcementactionpartnership.org/peel-policing-principles/. ↵

- Edward Maguire & Megan Oakley, Policing Protests: Lessons from The Occupy Movement, Ferguson and Beyond.12 (2020), https://www.hfg.org/hfg_reports/policing-protests-lessons-from-the-occupy-movement-ferguson-and-beyond/. ↵

- Another source of what is occurring in other communities is the Bridging Divides Initiative at Princeton University. https://bridgingdivides.princeton.edu/. ↵

- Community Relations Service, Event Marshals: Maintaining Safety During Public Events. (last modified September 5, 2023),.https://www.justice.gov/crs/our-work/training/event-marshals; Bridging Divides Initiative, Elevating De-Escalation and Community Safety Approaches, https://bridgingdivides.princeton.edu/policy/elevating-community-safety-and-de-escalation-approaches; Gabrielle T. Isaza &Robin S. Engel, Agency Implementation: Applied De-escalation Tactics: Train-the-Trainer Program Final Report (2024), https://portal.cops.usdoj.gov/resourcecenter/Home.aspx?item=cops-r1162. ↵

- Divided Community Project. Tools for Building Trust: Designing Law Enforcement–Community Dialogue and Reacting to the Use of Deadly Force and Other Critical Law Enforcement Actions 19-20 (Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2024) (discussing advantages of reacting to members of the crowd as individuals). ↵

- Community Relations Service, Event Marshals: Maintaining Safety During Public Events. (last modified September 5, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/crs/our-work/training/event-marshals. ↵

- Meg Anderson, Police Say ICE Tactics Are Eroding Public Trust in Local Law Enforcement, NPR (March 30, 2025); https://www.npr.org/2025/03/30/nx-s1-5304236/police-say-ice-tactics-are-eroding-public-trust-in-local-law-enforcement. ↵

- See FEMA, ICS Resource Center, https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/is/icsresource/trainingmaterials/ (providing training resources). ↵

- See generally Jeremy Bauer-Wolf, Lessons from Spencer’s Florida Speech, Inside Higher Education (Oct. 22, 2017). ↵

- See generally Sahnnon Najmabadi, Texas A&M Spent More Than a Quarter-Million Dollars to Draw Attention from Richard Spencer’s 2016 Visit to Campus, Texas Tribune (March 9, 2018). ↵

- St. Louis, Missouri, Mayor Tishaura O. Jones.,Statement on Planned Protest Friday (May 3, 2024), https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/mayor/news/slu-planned-protest-may-3-2024.cfm. ↵

- Clifford Stott, Leveraging Crowd Psychology to Prevent Violence, Police Chief Online, September 18, 2024, https://www.policechiefmagazine.org/leveraging-crowd-psychology-prevent-violence/. ↵

- Jeremy Bauer-Wolf, Lessons from Spencer’s Florida Speech, Inside Higher Education (Oct. 22, 2017). ↵