Main Body

Ch. 1: Social Context and Physical Environment

The first reading presents a general overview of theories concerning the role of social contexts and physical environments in substance use, substance use disorders, and opportunities for prevention or treatment. These are often referred to as sociocultural theories, but that label does not provide sufficient emphasis about the role of environmental factors. Evidence points to many relevant social and environmental factors that play a role, such as:

- Family and family system dynamics

- Peer groups

- School and workplace

- Neighborhood and community

- Policy and enforcement

- National and global forces

In this first chapter you will read about:

- Social systems, the physical environment, and the social ecological model;

- Social norms theory;

- Social structure influences, culture/subculture and deviance theory, the impact of “isms,” and labeling theory; and,

- key terms used in relation to the social context of substance use and addiction.

Social Systems

Anthropologists argue that the use of substances can only be properly understood when placed within a social context: the family, social, school, work, economic, political and religious systems (Hunt & Barker, 2001). An obvious physical environment aspect of context that is important to consider has to do with a person’s access to alcohol or other drugs. In general, the physical environment produces opportunities and obstacles that shape the behavior of people living or functioning in those spaces and places. For example, a person who grows up in a warm southern climate may not have an opportunity to learn snowboarding. Someone living in a dangerous neighborhood may not build outdoor exercise into his or her regular daily routine. And, the nutritional value of a person’s diet is influenced by living in a “food desert” versus in an area where healthful foods are easily accessed and affordable. Specific to our discussion of substance use, we need to consider how difficult or easy it is to gain access to alcohol, tobacco, or other substances in the family home, school, workplace, peer group, or neighborhood.

One set of questions tracked over time in the U.S. national survey of middle and high school students called Monitoring the Future concerns how easy or difficult the students believe it is to obtain various substances. As you can see from Table 1, the 12th graders believed they had easier access to all of the substances (cigarettes not reported) than did 8th and 10th graders. We have no way of knowing for certain if access actually increased with age, only that belief in access increased; however, the belief may be based on reality.

Table 1. Percent of students responding “fairly” or “very” easy to obtain substances, 2016*

|

substance |

8th graders |

10th graders |

12th graders |

|

alcohol |

52.7 |

71.1 |

85.4 |

|

cigarettes |

45.6 |

62.9 |

— |

|

marijuana |

34.6 |

64 |

81 |

|

LSD |

6.9 |

15.2 |

28 |

|

heroin |

8.9 |

10.6 |

20 |

|

other narcotics |

8.9 |

16.8 |

39.3 |

|

cocaine |

11.0 |

14.9 |

28.6 |

*Table created from data presented in Monitoring the Future report for 2016.

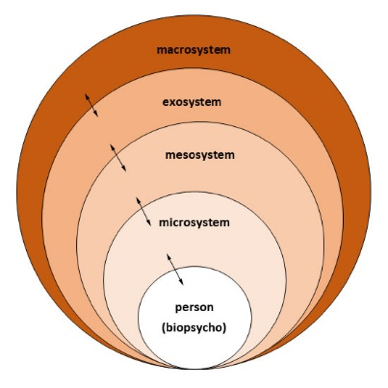

Social Ecological Model. The social ecological model presents a framework with great applicability for understanding human development and behavior within social systems and contexts. To consider how the social ecological model might apply to the problems of substance use, misuse, and addiction, we can start with the central sphere that represents the individual person. This innermost sphere contains what we have studied so far in relation to a person’s biological and psychological makeup—the biopsycho components from our earlier course modules. This is what the person brings to any interactions with the social or physical environments in which he or she functions. Next, we look at the many spheres of influence that form that individual’s social ecology: the micro, meso, exo, and macro systems with which individuals interact (see Figure 1). These systems influence us, we influence them, and they influence each other, which explains why there are arrows between the system levels in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Diagram representing social ecological model’s multiple system levels

Microsystem components include those social systems with which we directly interact on a regular basis: partners, immediate family members, close friends and others in our most personal, intimate sphere of daily living.

These people have a powerful effect on behavior through a number of mechanisms, including the way that they influence learning through delivering consequences (reinforcing or punishing) behaviors that we exhibit, as well as serving as the models for behavior related to social learning theory. They also shape our immediate environments. For example, they may make it easy to access alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs. While the microsystem influences our experiences, we have an influence on the microsystem, as well. Consider how a person’s substance use affects behavior, which in turn has an influence on his or her parenting, relating to an intimate partner, or interacting with friends.

These people have a powerful effect on behavior through a number of mechanisms, including the way that they influence learning through delivering consequences (reinforcing or punishing) behaviors that we exhibit, as well as serving as the models for behavior related to social learning theory. They also shape our immediate environments. For example, they may make it easy to access alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs. While the microsystem influences our experiences, we have an influence on the microsystem, as well. Consider how a person’s substance use affects behavior, which in turn has an influence on his or her parenting, relating to an intimate partner, or interacting with friends.

The microsystem influences and is influenced by the mesosystem, as well. The mesosystem components include those elements in the relatively immediate environment with which we routinely interact in ways that are less intimate than what happens within our microsystem. For some people this includes extended family and peers/friends with whom we are close but not as intimate. It might include the people with whom we work or go to school and it might include neighbors. For some people this might be a religious community. Health care providers might be part of the mesosystem if a person needs health or mental health care related to substance use.

The microsystem influences and is influenced by the mesosystem, as well. The mesosystem components include those elements in the relatively immediate environment with which we routinely interact in ways that are less intimate than what happens within our microsystem. For some people this includes extended family and peers/friends with whom we are close but not as intimate. It might include the people with whom we work or go to school and it might include neighbors. For some people this might be a religious community. Health care providers might be part of the mesosystem if a person needs health or mental health care related to substance use.

The exosystem is one more step removed in terms of regular interactions and direct impact. This includes social institutions with which we directly engage less frequently. Depending on the nature of our interactions, social institutions designed to provide services might be in the mesosystem or exosystem for a particular person or family. For example, this might distinguish between the office where someone works (mesosystem) and the company for whom the person works (exosystem). Or, it might distinguish between the person providing recovery treatment (mesosystem) and the agency where treatment is being provided (exosystem). The practices and policies of these social institutions (e.g., zero tolerance policies) influence the individual’s experience in the social environment through indirect interactions, often filtered to us through our intervening systems (mesosystem and microsystem). A significant component of the exosystem involves community policing and law enforcement around substance-related activities. For individuals involved with drug court by virtue of their substance-related activities, the team of intervention professionals might be part of the mesosystem. Social service delivery systems are part of the exosystem for many people.

The exosystem is one more step removed in terms of regular interactions and direct impact. This includes social institutions with which we directly engage less frequently. Depending on the nature of our interactions, social institutions designed to provide services might be in the mesosystem or exosystem for a particular person or family. For example, this might distinguish between the office where someone works (mesosystem) and the company for whom the person works (exosystem). Or, it might distinguish between the person providing recovery treatment (mesosystem) and the agency where treatment is being provided (exosystem). The practices and policies of these social institutions (e.g., zero tolerance policies) influence the individual’s experience in the social environment through indirect interactions, often filtered to us through our intervening systems (mesosystem and microsystem). A significant component of the exosystem involves community policing and law enforcement around substance-related activities. For individuals involved with drug court by virtue of their substance-related activities, the team of intervention professionals might be part of the mesosystem. Social service delivery systems are part of the exosystem for many people.

Finally, we have the macrosystem to consider. While few of us directly interact on a routine basis with the elements shaping the cultures and societies in which we live, they do have a powerful (though indirect) influence on our experience. Consider, for example, how change in the legal status of certain substances occurs, and how that change influences behavior at the individual level. Popular media provides an interface between what happens at the macrosystem (and exosystem) level and the more intimate levels of our social environments. It helps shape attitudes, values, beliefs, stereotypes, and stigma about substance use that are expressed by our mesosystem and microsystem members. Social workers and other professionals cannot afford to ignore the impact of policy, laws, and law enforcement patterns at the exosystem and macrosystem levels on the social context of substance use. For example, in many communities there exists a reciprocal relationship between the two problems of heroin use and the abuse of prescription pain medicines: as communities crack down prescription abuse, making the substances more difficult to obtain, problems with heroin seem to explode.

Finally, we have the macrosystem to consider. While few of us directly interact on a routine basis with the elements shaping the cultures and societies in which we live, they do have a powerful (though indirect) influence on our experience. Consider, for example, how change in the legal status of certain substances occurs, and how that change influences behavior at the individual level. Popular media provides an interface between what happens at the macrosystem (and exosystem) level and the more intimate levels of our social environments. It helps shape attitudes, values, beliefs, stereotypes, and stigma about substance use that are expressed by our mesosystem and microsystem members. Social workers and other professionals cannot afford to ignore the impact of policy, laws, and law enforcement patterns at the exosystem and macrosystem levels on the social context of substance use. For example, in many communities there exists a reciprocal relationship between the two problems of heroin use and the abuse of prescription pain medicines: as communities crack down prescription abuse, making the substances more difficult to obtain, problems with heroin seem to explode.

Within this framework, we can look more closely at theories concerning the mechanisms by which these social ecology elements have their impact, and at evidence concerning these different elements.

Social Norms Theory

Social norms are a key aspect of the social processes involved in substance use—both in terms of initiating use for the first time and in terms of misusing and using to excess. For example, most cultures that accept the use of alcohol also have norms related to the boundaries of acceptable use—when, where, by whom, and how much. Social norms also come into play because a person who believes that everyone else using alcohol or another substance, or at least approves of that substance’s use, is far more likely to use than a person who believes that it is not common or accepted in their social context.

Here is an interesting thought: if our public education messages suggest that way too many people binge drink or drive under the influence of substances or use marijuana on a regular basis, are we actually providing a social norm supporting these behaviors? Perhaps, instead, we need to tailor our messages differently. For example, consider the way anti-smoking campaigns have helped to reshape the nation’s social norms about tobacco use.

Here is an interesting thought: if our public education messages suggest that way too many people binge drink or drive under the influence of substances or use marijuana on a regular basis, are we actually providing a social norm supporting these behaviors? Perhaps, instead, we need to tailor our messages differently. For example, consider the way anti-smoking campaigns have helped to reshape the nation’s social norms about tobacco use.

Looking at the Monitoring the Future study results again, we can explore middle and high school students’ level of disapproval toward people who use substances. As you can see, occasional and regular use of substances gains more disapproval than trying it once or twice, and the level of disapproval for marijuana and alcohol use declines among the older 12th grade students compared to the younger groups of 8th and 10th graders (see Table 2). What is interesting to note is that the 12th graders seem to make a greater distinctions between types of substances than do the younger students: they disapprove more strongly than the younger students about LSD and heroin, and equally strongly about cocaine, but less strongly about alcohol and marijuana.

Table 2. Percent of students disapproving or strongly disapproving of people who…*

|

substance use pattern |

8th graders |

10th graders |

12th graders |

|

try one or two drinks of an alcoholic beverage |

52.6 |

41.8 |

28.8 |

|

take one or two drinks nearly every day |

79.1 |

78.6 |

71.8 |

|

have five or more drinks once or twice each weekend |

84.9 |

80.8 |

74.2 |

|

try marijuana once or twice |

70.1 |

52.6 |

43.1 |

|

smoke marijuana occasionally |

77.5 |

61.9 |

50.5 |

|

smoke marijuana regularly |

82.3 |

73.5 |

68.5 |

|

try heroin once or twice without using a needle |

85.6 |

90.2 |

93.8 |

|

take heroin occasionally without using a needle |

86.7 |

90.9 |

94.0 |

|

try cocaine once or twice |

86.8 |

87.9 |

86.6 |

|

take cocaine occasionally |

89.3 |

90.8 |

90.6 |

|

take LSD once or twice |

55.2 |

69.5 |

82.4 |

|

take LSD regularly |

57.6 |

74.9 |

92.4 |

*Table created from data presented in Monitoring the Future report for 2016.

Social norms about alcohol and other substance use also tend to be tied to ethnic identity. For example, there exist many drinking-related stereotypes about Irish Americans and Americans with Russian roots. These ethnic stereotypes can have a significant effect on a person’s decisions about drinking and drinking to excess. On the other hand, cultural prohibitions around drinking to the point of intoxication may be strong in a person’s cultural context. This social disapproval of excessive use (misuse) can be a protective factor against substance use becoming a substance use disorder.

Social Structure Influence Theories.

A number of theories draw from the science of sociology to explain the phenomena of substance use, misuse, and addiction. These theories “view the structural organization of a society, peer group, or subculture as directly responsible for drug use” (Hanson, Ventruelli, & Fleckenstein, 2015, p. 78).

Culture and subculture. Policy is a form of intervention heavily influenced by theories about the origin of the problems to which it is responding. To a large extent, policy also is influenced by a culture’s values and belief systems, such as the philosophy concerning whether the problem of substance use is better addressed through punishment or treatment. Cultural systems are even responsible for defining what is a drug in the first place. For example, in the majority culture of the United States, hallucinogenic substances like peyote are defined as drugs of abuse. However, according to anthropologists, peyote religion among certain Native American groups defines this substance quite differently (Hill, 2013).

Or, consider the argument that fast food has addictive potential—is a fast food burger to be considered a drug and the fast food restaurants responsible for causing an addiction like drug trafficking?

Subculture is about groups that form within a larger culture. The values, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors within the subculture group may complement or contradict those of the larger cultural context. When they are contradictory, deviance theory may come into play. According to deviance theory, a person (or group) elects to engage in behaviors disapproved of by the conventional “majority” culture specifically because of that disapproval. These individuals embrace their deviance identity—the label becomes an important aspect of identity. Why would someone want to belong to a deviant subculture or group? For many people, it is a matter of belonging somewhere, anywhere, being better than belonging nowhere. Participating in deviant behavior seems a small price to pay for admission to the group. For others it is a means of differentiating self from others—particularly from those who represent the conventional culture. For example, it is one way of making clear to yourself and the world that you are your own person, distinct from who your parents are. Having strong prosocial bonds with members of the conventional culture is a protective force against deviance—the extent to which a person desires approval and wishes to avoid disapproval of the people with whom they have these prosocial bonds helps them make choices that conform to convention (Sussman & Ames, 2008).

Labeling theory suggests that other people’s perceptions of us, the labels they apply to us, have a strong influence on our own self-perceptions (Hanson, Venturelli, & Fleckenstein, 2015). The individual then has the choice of acting in accordance with the labels (e.g., drinking to excess as an “alcoholic”) or acting differently so as to shed the label (e.g., quitting drinking ordrinking only in moderation). In addition, theory suggests that when individuals have weak bonds to conventional society, there is less motivation to conform to conventional social norms and expectations. Hence, they are more likely to deviate from those norms. They have less “stake in conformity” than others who choose to behave in ways that comply with conventional norms.

Labeling theory suggests that other people’s perceptions of us, the labels they apply to us, have a strong influence on our own self-perceptions (Hanson, Venturelli, & Fleckenstein, 2015). The individual then has the choice of acting in accordance with the labels (e.g., drinking to excess as an “alcoholic”) or acting differently so as to shed the label (e.g., quitting drinking ordrinking only in moderation). In addition, theory suggests that when individuals have weak bonds to conventional society, there is less motivation to conform to conventional social norms and expectations. Hence, they are more likely to deviate from those norms. They have less “stake in conformity” than others who choose to behave in ways that comply with conventional norms.

The impact of “isms.” Issues of racism, classism, sexism, and other forms of “ism” have a powerful impact on individual’s experience of the social world, as well as on their physical environments. Thus, oppression, discrimination, and exploitation based on racial, ethnic, social class, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religious, disability, or national origin factors are integral to understanding the social context of substance use disorders. These forms of societal abuse fall along a complex continuum from the obvious and overt to the subtle and covert (Edmund & Bland, 2011). Exposure to repeated instances of microaggression may contribute to substance use, as well. Ethnic and racial microaggressions are events that leave the person on the receiving end feeling put down or insulted because of race or ethnicity—regardless of the intent by persons delivering the messages (Blume, Lovato, Thyken, & Denny, 2011). In a study of undergraduate college students, these microaggression experiences were associated with higher rates of binge drinking and experiencing more of the negative consequences associated with drinking (Blume, Lovato, Thyken, & Denny, 2011). Similarly, a study of college students demonstrated that the odds of regular marijuana use increased as a function of the number of microaggressions experienced (Pro, Sahker, & Marzell, 2017). And, again, the same relationship was observed in a study of Native American students and use of illicit drugs (Greenfield, 2015). Thus, it is important for social workers and other professionals to consider the heavy toll exacted on individuals who experience incidents of societal abuse, and how substance use may be related to these cumulative trauma experiences. Not only does this include those who experience it first-hand, but also those who witness it (second-hand)

The impact of “isms.” Issues of racism, classism, sexism, and other forms of “ism” have a powerful impact on individual’s experience of the social world, as well as on their physical environments. Thus, oppression, discrimination, and exploitation based on racial, ethnic, social class, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religious, disability, or national origin factors are integral to understanding the social context of substance use disorders. These forms of societal abuse fall along a complex continuum from the obvious and overt to the subtle and covert (Edmund & Bland, 2011). Exposure to repeated instances of microaggression may contribute to substance use, as well. Ethnic and racial microaggressions are events that leave the person on the receiving end feeling put down or insulted because of race or ethnicity—regardless of the intent by persons delivering the messages (Blume, Lovato, Thyken, & Denny, 2011). In a study of undergraduate college students, these microaggression experiences were associated with higher rates of binge drinking and experiencing more of the negative consequences associated with drinking (Blume, Lovato, Thyken, & Denny, 2011). Similarly, a study of college students demonstrated that the odds of regular marijuana use increased as a function of the number of microaggressions experienced (Pro, Sahker, & Marzell, 2017). And, again, the same relationship was observed in a study of Native American students and use of illicit drugs (Greenfield, 2015). Thus, it is important for social workers and other professionals to consider the heavy toll exacted on individuals who experience incidents of societal abuse, and how substance use may be related to these cumulative trauma experiences. Not only does this include those who experience it first-hand, but also those who witness it (second-hand)

“Isms” play a role in creating and maintaining marked disparities in opportunity and resources between social groups at the level of neighborhoods, schools, communities, workplaces, and populations. These include discrepancies in media portrayal, access or barriers to drugs, disparate exposure to advertising and media portrayals of drugs, access to desirable alternatives to drug use, availability and cultural competence of prevention and treatment options, and the consistency with which sanctions for drug-related activities are imposed (e.g., variable implementation of zero tolerance policies or criminal justice system sanctions). Recall from our Module 1 readings how the War on Drugs related to tremendous racial and ethnic disparities in the nation’s incarceration rates.

“Isms” play a role in creating and maintaining marked disparities in opportunity and resources between social groups at the level of neighborhoods, schools, communities, workplaces, and populations. These include discrepancies in media portrayal, access or barriers to drugs, disparate exposure to advertising and media portrayals of drugs, access to desirable alternatives to drug use, availability and cultural competence of prevention and treatment options, and the consistency with which sanctions for drug-related activities are imposed (e.g., variable implementation of zero tolerance policies or criminal justice system sanctions). Recall from our Module 1 readings how the War on Drugs related to tremendous racial and ethnic disparities in the nation’s incarceration rates.

Consider how social justice concerns and disparities function at the neighborhood and community level. For example, consider the difference between empowered and distressed neighborhoods to defend against the intrusion of illegal drug trafficking and the crime, violence, and exploitation that accompany drug trafficking. Also consider how difficult it becomes in many communities to gain access to evidence-supported prevention or treatment services that are accessible in terms of being affordable, close to home, culturally appropriate, and developmentally (age) appropriate.

What Comes Next?

Now you have been introduced to several theories and models concerning the ways that the physical environment and social contexts might play a role in substance use, misuse, and addiction. Let’s turn our attention to specific arenas where the social world has an impact. This would be the microsystem elements of family and peer group influences. But, let’s not forget the significance of the larger social systems and social institutions that are involved, as well.