Job Search Communications

Employment Access, Equity & Opportunity

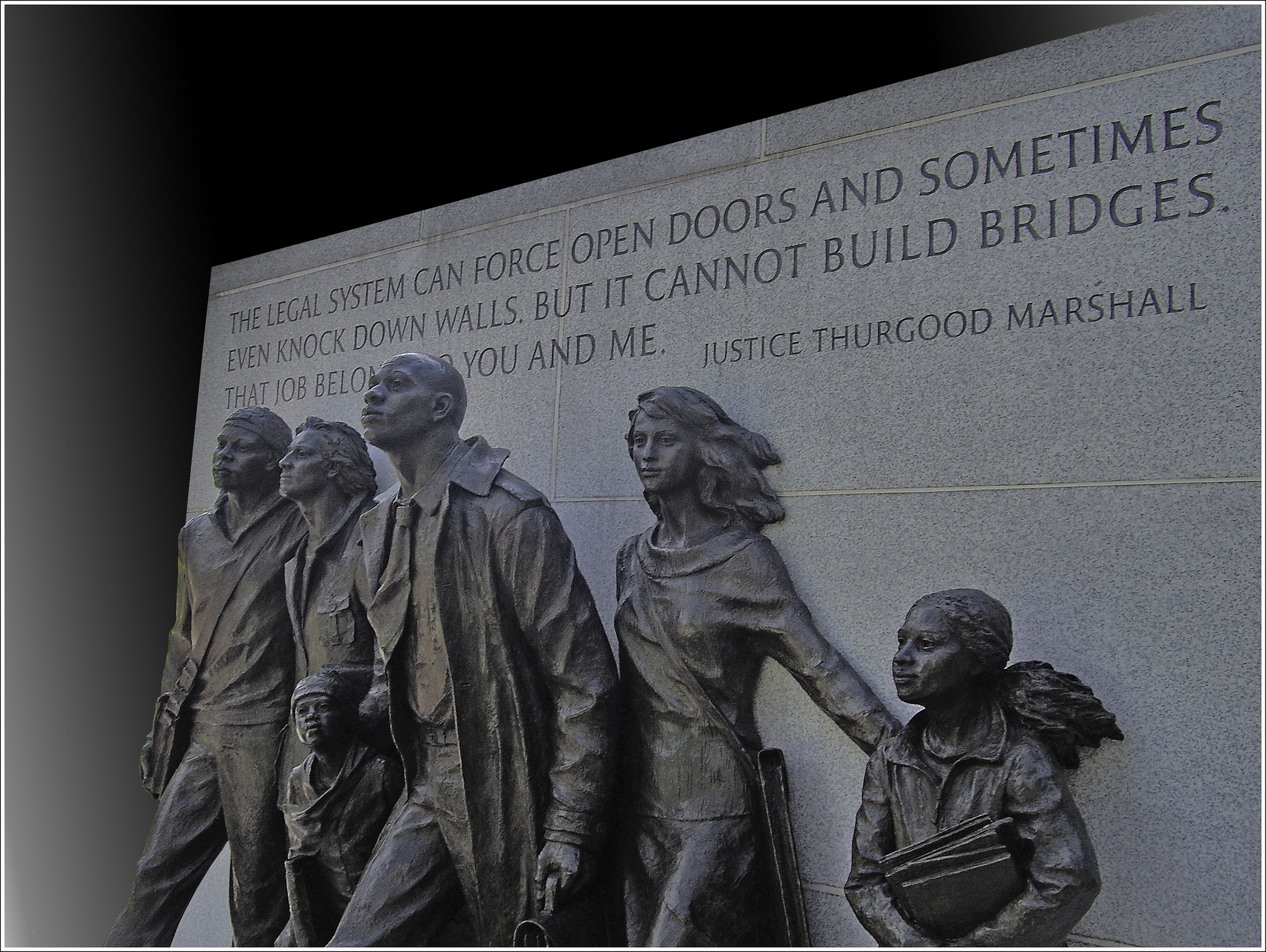

“Virginia Civil Rights Memorial — State Capitol Grounds Richmond (VA) 2012” by Ron Cogswell / CC BY

In this section, we turn our attention to social issues that affect the workplace—specifically, questions of social diversity and the importance of equitable employment opportunities in the United States.

The U.S. is a diverse and multifaceted country. And yet, social and historical forces combine to create an imbalance in the workforce—in the access groups of people have to educational and economic power and in the ways contributions to the workforce are viewed and valued.

As a society, we have realized that diverse teams, companies, and groups of people are better equipped to innovate and address the needs of the customers they serve. Companies of all sizes are working to address these issues in their hiring practices and in the ways they foster positive, inclusive work environments for their employees.

How will you work to make the U.S. workforce more equitable and inclusive?

Most importantly, we hope that you recognize this as unfinished business. We encourage you to think of this as a discussion and as a dynamic, ever-changing part of your professional life. The way things are now are not the way they will be in 20 or 30 years and you will be part of that change. How the workforce of 2050 looks like is, in part, up to you. The goal in this chapter is to give you the opportunity to think about your contribution to that future, where you fit into picture, the impact you will have in your own sphere of influence.

History & Context

Perhaps you have noticed that most employers include a statement about being and “equal opportunity employer” in their job advertisements and recruiting materials. The Ohio State University includes the following statement in the footer of their Careers website (jobsatosu.com):

The Ohio State University is an equal opportunity employer. All qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, disability status, or protected veteran status.

Statements such as this are so commonplace that you might not spend much time thinking about them, but they reveal something important about the history of employment law and practices in the United States.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 (CRA), originally introduced by President Kennedy and signed into law by President Johnson on July 2, 1964, was a major achievement of the Civil Rights Movement. The Act made discrimination illegal at the Federal level, outlawing practices like segregated schools, public restrooms and water fountains. Title VII of the Act specifically addressed the problem of employment discrimination, establishing the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, whose mission is investigating and enforcing anti-discrimination laws. Here, you can watch President Johnson’s Remarks on Signing the Civil Rights Bill:

Why was this legislative action necessary? In the decades before the CRA, decisions about recruiting and hiring were at times openly made on the basis of race, sex, nationality, etc. You could even see that the “help wanted” section of newspapers in the early 20th century were often separated jobs for men, women, and, in some cases, by race. Job ads might also specify marital status, as employers were looking for unmarried “girls” to fill certain roles. Low-paying and unskilled jobs were more likely to be reserved for women and minorities, greatly limiting their employment opportunities.

You can see some examples of segregated job advertisements here (from the Learn NC website).

One impact of the CRA was the establishment of “protected classes,” which are ways of classifying groups of people at risk of being systematically singled out for discrimination and explicitly prohibiting such discrimination. Initially, the protected classes identified were race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. Over time, anti-discrimination laws have evolved and the original Act has been amended to meet the evolving needs of the American workplace.

This timeline shows the dates and legislation that officially recognized the protected classes:

- 1964: Race, color, religion, sex, or national origin

- 1967: Age – 40 or older (Age Discrimination in Employment Act)

- 1974: Veteran status (Vietnam Era Veterans’ Readjustment Assistance Act of 1974 and Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act)

- 1990: Disability (Americans with Disabilities Act)

- 2008: Genetic information (Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act)

The laws also includes provisions for people who have filed charges to protect them from experiencing retaliation or stigma that might affect their careers.

As explained by the EEOC, “Every U.S. citizen is a member of some protected class, and is entitled to the benefits of EEO law. However, the EEO laws were passed to correct a history of unfavorable treatment [emphasis added] of women and minority group members” (National Archives, n.d.).

The ever-evolving nature of the laws and discourse in our society is evident in the status of the LGBT community as a protected class. The EEOC considers discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation (2012) or gender identity (2015) as part of the “sex” protected class. A number of state and local governments have passed specific anti-discrimination laws related to sexual orientation and gender identity. However, there are currently no explicit Federal protections in place.

Diversity & Inclusion in the U.S. Workplace

It is important to remember that making discrimination illegal does not mean that it no longer happens. The purpose of the EEOC and the legal system in the United States is to continue to refine the protections and defend people’s right to work and thrive in their professional lives.

Even if the law levels the playing field, historical and social realities can have real consequences on an individual’s access and equity. As an example, we might examine the impact of the CRA on education achievement and income levels. As Beasley (2012) articulates in Opting Out,

“[The Civil Rights] act, coupled with the initiative of a number of colleges and universities across the country, produced a significant rise in black college attendance. By 2000, nearly 18 percent of African Americans aged 25 to 54 had received at least a bachelor’s degree compared with only 7 percent in 1969 (US Census Bureau 1973, 2001). While college education is inarguably a key factor in the upward mobility of African Americans, blacks with college degrees still face considerable hurdles. Indeed, over this same period of time, the difference in average earnings of black and white college graduates dropped by only one percentage point (US Census Bureau 1973, 2001). Thirty-five years after racial discrimination was legally banned, the question remains: what continues to hold African Americans back, if not the law?”

So, if the CRA “resolved” issues surrounding employment discrimination, why aren’t hiring practices fair and completely unbiased? Why worry about how underrepresented groups of people fair in the workplace?

Let’s consider an oft-cited example involving professional orchestras. Up until the 1970s, musicians in symphony orchestras were almost entirely white males. Arguing that the decisions about who was qualified were entirely merit-based, the decision makers agreed to a new process of blind auditions, where the musicians would perform behind a screen, removing race, gender or any other visible factors from the evaluation process. The result was that women were between 25 and 46 percent more likely to be hired than men than they were during the old audition process; a shift that has radically altered the demographics of professional orchestras (Miller, 2016). This example asks us to consider how simply removing sex or gender from the process of evaluating an applicant could change the outcome.

Disparities in employment combined with shifts like the blind auditions have raised important questions about the ways in which social perceptions, stereotypes, and biases impact hiring and job performance related decisions. If a screen changes hiring outcomes for orchestras, how are these forces playing out in other parts of the job market?

The causes and effects of discrimination are varied and multidimensional, so researchers working in a variety of fields have conducted studies to better understand the impact that bias can have on workforce demographics and power structures. Following are just a few examples of studies that demonstrate the impact of social biases in the workplace.

Racial Bias

In a significant study conducted in Chicago and Boston in 2001–2002, researchers submitted résumés to a variety of advertised jobs, but some used “white-sounding” names and some “black-sounding” names, which were selected based on census data for common names in the white and black communities. They found résumés with names like Emily Walsh and Greg Baker received about 50% more callbacks for interviews than those with names like Lakisha Washington or Jamal Jones. Further examination of the difference between how better quality résumés were received by employers revealed that those with the “white-sounding names” benefitted significantly more from a higher quality résumé than those presumed to come from black applicants (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004).

Gender Bias

In a different study researching names and gender, Moss-Racusin, et al. (2012), asked science faculty to evaluate identical resumes for the position of lab supervisor. The candidate named “John” was overwhelmingly ranked as more qualified than the candidate named “Jennifer” in spite of their identical credentials. The candidate perceived as male was also offered a higher starting salary.

A number of studies have shown that perceptions of women’s abilities can affect how they are treated in the workplace. In a study that examined how candidates’ competency was rated, male candidates were given preference over women for a job that required skills in mathematics, even when data shows equal competence between genders (Reuben, Sapienza, & Zingales, 2014). In both of the aforementioned studies, it is important to note that bias was present regardless of participant gender.

Similarity Bias

In a study published in the American Sociological Review, Rivera (2012) identifies the importance interviewers place on “cultural matching,” meaning that employers prioritized similarities like “leisure pursuits, experiences, and self-presentation styles” above productivity or job-related skills. This study illustrates the effect of similarity bias, in which factors like shared interests or communication style affect how potential employees are evaluated.

It is human nature to gravitate towards like people (thus the similarity bias mentioned above). In diverse group (or team) settings: “people tend to view conversations as a potential source of conflict that can breed negative emotions” and, as a result, “these emotions . . . can blind people to diversity’s upsides: new ideas can emerge, individuals can learn from one another, and they may discover the solution to a problem in the process” (Chhun, 2010).

We must, however, remember the perils of our tendency toward insularity: “Though people often feel more comfortable with others like themselves, homogeneity can hamper the exchange of different ideas and stifle the intellectual workout that stems from disagreements” (Chhun, 2010).

Benefits of Diversity

And, in addition to basic principles of fairness and equality, it turns out that a diverse workforce is more profitable. Researchers and companies have found that diverse teams improve outcomes, increase productivity, and innovate at higher rates:

- Forbes conducted interviews and distributed surveys to 321 executives of global companies and found that the vast majority agreed that diversity drives innovation. To that end, three-quarters of respondents planned to “leverage diversity for innovation and other business goals” (Forbes Insights, 2011).

- A McKenzie study demonstrated a correlation between diverse executive boards and higher returns on equity (Barta, Kleiner, Neumann, 2012).

Ultimately, research tends towards the benefits of a diverse and multi-talented workforce. More and more companies are recognizing the economic rewards of recruiting, retaining, and cultivating diversity in their ranks.

These are evolving issues that raise complex, difficult questions about what it means to have equal employment opportunities. It will be important for you to be aware of these issues and able to participate in discussions about diversity and inclusion, no matter who you are.

Discussion & Reflection

What does “diversity” mean to you? How do you think about, define or use the term?

Consider how often you find yourself interacting with people who “look like” you in terms of race, ethnicity, and gender. Do you have opportunities to work in diverse groups? Why or why not?

What made it possible for you to be where you are, in terms of your education and prospects for future employment? Consider both tangible (monetary, for example) and intangible (encouragement from family members, for example) forms of support. What pushed you down this path?

Consider the impact of having socio-economic opportunities for groups of people systematically limited. What are the systemic effects of job discrimination? What happens to communities if large numbers of its members have a similarly limited access to gainful employment (or education or fair housing)?

References

Barta, T., Kleiner, M. & Neumann, T. (2012). Is there a payoff from top-team diversity? McKenzie Quarterly. Retrieved from: http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/is-there-a-payoff-from-top-team-diversity

Beasley, M. (2011). Opting out: Losing the potential of America’s young black elite. Chicago: U of Chicago P.

Bertrand, M. & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review, 94, 991-1013. http://www.aeaweb.org/articles.php?doi=10.1257/0002828042002561

Chhun, B. (2010). Better decisions through diversity. Kellogg Insight. Retrieved from: http://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/better_decisions_through_diversity

Forbes. (2011). Global diversity and inclusion: Fostering innovation through a diverse workforce. Forbes Insights. Retrieved from: http://www.forbes.com/forbesinsights/innovation_diversity/

Miller, C. (2016, February 25). Is blind hiring the best hiring? The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/is-blind-hiring-the-best-hiring.html?_r=0

Moss-Racusin, C., Dovidio, J., Brescoll, V., Graham, M., & Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. PNAS, 109(41), 16474-16479. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211286109

National Archives. (n.d.). Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) Terminology. Retrieved from http://www.archives.gov/eeo/terminology.html

Reubena, E., Sapienzab, P. & Zingalesc, L. (2014). How stereotypes impair women’s careers in science. PNAS, 111(12), 4403-4408. doi:10.1073/pnas.1314788111

Rivera, L. (2012). Hiring as cultural matching: The case of elite professional service firms. American Sociological Review, 77(6), 999–1022. doi:10.1177/0003122412463213