Ch. 1: Nature and Effects Sedative-Hypnotics and CNS Depressants

The topic of sedative-hypnotics and CNS depressants overlaps considerably with the topic of prescription drug abuse (more about this in Module 12). Whether used as prescribed or used without a prescription, a drug still has the same actions on the brain, body, and behavior. Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) made the following statement to the United States Congress on September 22, 2010:

CNS depressants, typically prescribed for the treatment of anxiety, panic, sleep disorders, acute stress reactions, and muscle spasms, include drugs such as benzodiazepines (e.g., Valium, Xanax) and barbiturates (e.g., phenobarbital)—which are sometimes prescribed for seizure disorders. Most CNS depressants act on the brain by affecting the neurotransmitter gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA), which works by decreasing brain activity. CNS depressants enhance GABA’s effects and thereby produce a drowsy or calming effect to help those suffering from anxiety or sleep disorders. These drugs are also particularly dangerous when mixed with other medications or alcohol; overdose can suppress respiration and lead to death. The newer non-benzodiazepine sleep medications, such as zolpidem (Ambien), eszopiclone (Lunesta), and zaleplon (Sonata), have a different chemical structure, but act on some of the same brain receptors as benzodiazepines and so may share some of the risks—they are thought, however, to have fewer side effects and less dependence potential.

CNS depressants, typically prescribed for the treatment of anxiety, panic, sleep disorders, acute stress reactions, and muscle spasms, include drugs such as benzodiazepines (e.g., Valium, Xanax) and barbiturates (e.g., phenobarbital)—which are sometimes prescribed for seizure disorders. Most CNS depressants act on the brain by affecting the neurotransmitter gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA), which works by decreasing brain activity. CNS depressants enhance GABA’s effects and thereby produce a drowsy or calming effect to help those suffering from anxiety or sleep disorders. These drugs are also particularly dangerous when mixed with other medications or alcohol; overdose can suppress respiration and lead to death. The newer non-benzodiazepine sleep medications, such as zolpidem (Ambien), eszopiclone (Lunesta), and zaleplon (Sonata), have a different chemical structure, but act on some of the same brain receptors as benzodiazepines and so may share some of the risks—they are thought, however, to have fewer side effects and less dependence potential.

This statement summarizes many of the key points relevant to Module 8 concerning the nature, effects, and use of sedative-hypnotic and CNS depressant drugs. Let’s look into these points in a little more detail.

What are Sedative-Hypnotics and CNS Depressants?

Sedative-hypnotic, tranquilizer, and central nervous system (CNS) depressant drugs slow down brain activity, calming brain excitability. This effect is typically mediated through enhancing the activity of GABA neurotransmitter activity (Begun, 2020)—GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) is one of the brain’s main inhibitory neurotransmitters and plays a key role in the regulation of anxiety (https://thebrain.mcgill.ca/flash/i/i_01/i_01_m/i_01_m_ana/i_01_m_ana.html). The result is a general calming influence on anxiety and acute stress reactions; sleepiness or drowsiness may also be induced. These types of drugs are often used medically in the treatment or management of conditions like anxiety or panic disorders (anxiolytics), acute stress, insomnia (sleeplessness/sleep disorder), epilepsy/seizure disorders, or muscle spasms (tranquilizers). Sedative compounds produce a calming effect, reducing excitability in the central nervous system, while hypnotic compounds induce sleep or intense drowsiness (Dupont & Dupont, 2005; NIDA, 2018)—switching off brain activity.

Common forms of sedative-hypnotic and CNS depressants, other than alcohol, identified by NIDA (2018) include:

- benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam/Valium®, clonazepam/Klonopin®, alprazolam/Xanax®, lorazepam/Ativan®, triazolam/Halcion®, estazolam/Prosom®/, chlorodiazepoxide/Librium®) [street names include: candy, downers, tranks/tranqs] [note that “bennies” are not benzodiazepines, they refer to a brand of amphetamine] [other names for Xanax®: bicycle parts or bicycle handle bars; for Konopin®: benzos, K, K-Pin, Super Valium https://ndews.umd.edu/sites/ndews.umd.edu/files/dea-drug-slang-terms-and-code-words-july2018.pdf]

- barbiturates (e.g., mephobarbital/Mebaral®, phenobarbital/Lumninal®, pentobarbitol sodium/Nembutal®, amobarbital/Amytal®, butabarbital/Butisol®) [street names include: barbs, phennies, reds, yellows, yellow jackets]

- non-benzodiazipine sedative hypnotics/sleep medications (zolpidem/Ambien®, eszopiclone/Lunesta®, zaleplon/Sonata®) [street names include: sleep medications or references to sleep/forgetting]

Since these drugs are most often prepared in pill, capsule, or liquid form, they are most often swallowed. However, a form of misuse involves crushing the pills or emptying the contents of a capsule and either inhaling (“snorting”) or injecting the contents. These modes of administration bypass the digestive system and produce a more immediate and possibly more intense response. They also involve additional health risks—such as, risk of infection and communicable disease transmission (HIV, hepatitis) from shared needles. Less commonly used outside of medical/hospital settings are anesthetic drugs, such as propofol (contributing to the death of singer Michael Jackson). Anesthetics used in medical (and veterinary) settings may be in an oral form or a form to be injected, administered intravenously (IV; e.g., propofol), or inhaled as a gas (e.g., nitrous oxide).

Epidemiology

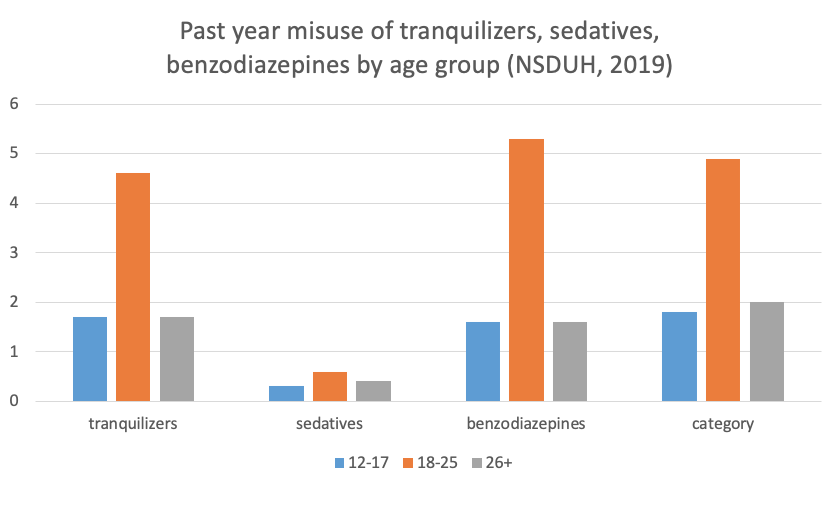

In the United States, the misuse of tranquilizers or sedatives is less common than for many other types of psychoactive substances. According to data from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH, 2019), an estimated 0.7% of individuals aged 12 and older engaged in the current (past month) misuse of these types of substances during 2018. However, in the past year, 2.0% reported benzodiazepine misuse, 2.1% reported tranquilizer misuse, and 0.5% reported sedative misuse. The age group most likely to report past year misuse of these substances occurred among emerging adults aged 18-25 years.

Effects

The CNS effects of sedative-hypnotic compounds occur on a continuum, “depending on the dose, beginning with calming and extending progressively to sleep, unconsciousness, coma, surgical anesthesia, and, ultimately, to fatal respiratory and cardiovascular depression” (Dupont & Dupont, 2005, p. 219). The effects at low doses are not unlike the effects of alcohol—impaired cognitive and motor functioning—and the sedating effect of many antihistamines. Use as prescribed or misuse can be accompanied by the following effects (NIDA, 2018):

- slurred speech

- poor concentration

- confusion

- memory problems

- headache

- light-headedness/dizziness

- dry mouth

- uncoordinated movements

- low blood pressure

- slowed breathing rate.

Drugs in this group are potentially addictive, some with much greater addictive potential than others. These drugs have different DEA scheduling assignments depending on their addictive potential and approved medical uses in the U.S., ranging from Schedule I to IV (see https://d14rmgtrwzf5a.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/nida_commonlyabuseddrugs_rx_final_printready.pdf).

Combining CNS depressants with other substances is potentially dangerous. For example, both alcohol and benzodiazepines have the effect of slowing/suppressing respiration. Thus, if these two substances are combined, the risk of someone’s breathing being dangerously slowed or stopped increases since the respiratory effects are additive.

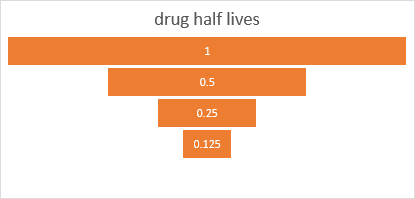

Different forms of sedative-hypnotic and CNS depressant drugs have different half-lives, meaning that some are longer-acting than others. Consider, for example, the news media coverage of celebrities reporting sedating, confusion, coordination, and amnesic effects of non-benzodiazepine sleep medications 8 hours after these drugs were consumed for insomnia (e.g., Tiger Woods, Charlie Sheen, Elon Musk, Sean Penn). Some others in this category of drugs wear off in 2-4 hours.

Tolerance and withdrawal. Tolerance is relatively quickly developed with repeated administration of barbiturates, contributing to a person’s likelihood of increasing the dose used over time (Dupont & Dupont, 2005). Tolerance can develop to any of the sedative hypnotic and CNS depressant drugs (NIDA, 2018. In addition, individuals using barbiturates may also develop cross-tolerance to benzodiazepines and to alcohol (Dupont & Dupont, 2005)—meaning that a person who switches type of drug within this type may already experience tolerance to the new drug. This, too, contributes to the risk of overdose. Overdose with these drugs is dangerous because of the drugs’ effects on breathing—slowing it down or stopping breathing to the point of brain damage from hypoxia (lack of sufficient oxygen to the brain), coma, or death (NIDA, 2018). Overdose from benzodiazepines can be treated as an emergency situation with a benzodiazepine receptor antagonist drug (e.g., flumazenil injection). Withdrawal symptoms from CNS depressants include (NIDA, 2018):

- intense cravings

- seizures

- anxiety/agitation

- insomnia

- overly active reflexes, shakiness

- increased heart rate

- increased blood pressure

- increased body temperature

- hallucinations.

Medically managed withdrawal and detoxification from these drugs (particularly barbiturates), just as in the case of alcohol withdrawal, is recommended given the potential severity of acute withdrawal symptoms (including seizures). Ideally, the dose is gradually reduced over time (“weaning” form of detoxification) or safer substitute medications are used to taper off the primary drug.

Fetal Exposure

The evidence concerning teratogenic effects of benzodiazepines is somewhat unclear and inconsistent, possibly due to variations in study methodology and study participants. An early review indicated that the majority of prenatally exposed infants developed normally and that the few showing neurodevelopmental deficits “caught up” by 4 years of age (McElhatton, 1994). However, a subsequent study demonstrated a behavioral effect (increased internalizing behavior) among toddler/pre-school aged children experiencing long-term prenatal exposure to benzodiazepines compared to unexposed siblings—an effect unlikely to be attributable to environmental factors (Brandlistuen et al., 2017). The authors indicate that these drugs do cross the placental barrier, meaning that there is a potential for affecting fetal development. The greatest health and developmental risks of prenatal exposure to these drugs appear to occur late in the final trimester and during birth with babies exhibiting listlessness (“floppy infant syndrome”), apnea (interrupted breathing), and/or neonatal withdrawal symptoms (McElhatton, 1994).