Ch. 2: Focus on OTC and Prescription Drug Misuse

Let’s begin with debunking a myth commonly held in the general public: that over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, sold in general drug and grocery stores, are safe because they do not require a prescription to purchase. The simple truth is that ANY drug, whether OTC or prescription, is potentially dangerous if misused. All drugs have potential side effects. This is a common feature of both prescription and OTC drugs. It is also of concern with many herbal remedies and dietary supplements marketed as health or mental health promoting products. Consider, for example, the scientific debate concerning the effectiveness and safety of St. John’s Wort for treating depression—in some studies it was no better than placebo, in others it was equally beneficial as prescription medications, and it is clearly dangerous to use in combination with other medications (or substances), including other anti-depressants, birth control pills, pain medication, heart medication, cancer and HIV treatments, and others (NCCIH, 2018). OTC treatments often lack strong evidence of effectiveness, may not be thoroughly evaluated for negative side effects, and may delay a person seeking evidence-supported treatment options.

So, what is the difference between OTC and prescription products? The main difference goes back to what we previously learned about the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) controlled substance schedules for classifying drugs. The federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA) defines regulations for the manufacture, importing, possession, use and distribution of different drugs. In some cases, the major difference in classifying a substance as needing a prescription versus being accessible as an OTC medication lies in the concentration of active ingredients the product contains. Thus, when taken as directed, there is little risk involved. That does not mean there is NO risk, only that the risk level is in a tolerable range for the general population. Risk levels, however, are considerably more difficult to judge for:

So, what is the difference between OTC and prescription products? The main difference goes back to what we previously learned about the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) controlled substance schedules for classifying drugs. The federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA) defines regulations for the manufacture, importing, possession, use and distribution of different drugs. In some cases, the major difference in classifying a substance as needing a prescription versus being accessible as an OTC medication lies in the concentration of active ingredients the product contains. Thus, when taken as directed, there is little risk involved. That does not mean there is NO risk, only that the risk level is in a tolerable range for the general population. Risk levels, however, are considerably more difficult to judge for:

- Children

- Adolescents

- Individuals with certain types of physical or mental conditions (including pregnancy)

- Individuals with a pre-existing substance use disorder.

What Is OTC Misuse About?

OTC abuse is not as large on the public radar as the topics of prescription misuse and misuse of illicit drugs or alcohol. But OTC products can be just as problematic when misused. This means use beyond or outside of the recommended dosing and/or to experience psychoactive effects with the product alone or mixed with other products (NIDA, 2017b). There are three types of OTC products commonly misused for psychoactive purposes for us to consider in greater detail; many other OTC products are misused for other physical or mental health effects.

Decongestants. Until relatively recently, pseudoephedrine (e.g., Sudafed®) was easily purchased as an OTC for managing cold, flu, and allergy symptoms of nasal congestion. Since 2005, it has become more tightly controlled. Although these medications are still available without a prescription, they are no longer fully OTC products in the United States. Their status is as a behind-the-counter (BTC) medication in some countries. BTC policy (in the U.S.) means that a person can purchase the substance without a prescription, but only through interacting with a pharmacist and only in small, designated amounts. The reason: pseudoephedrine can be used as an ingredient in the illegal manufacturing of methamphetamine. (We learned about this in a previous module). However, medications containing pseudoephedrine may abused on their own for other purposes: to promote weight loss or as a stimulant performance enhancer by athletes.

Cough Medicines. Dextromethorphan (DXM) is an ingredient commonly found in many OTC products intended as a cough suppressant. At recommended doses, DXM works on the part of the brain region that controls coughing. However, at extremely high doses (10-50 times the recommended), it becomes a psychotropic drug causing euphoria (sometimes referred to as “robotripping” or “skittling”—see NIDA, 2017b). The effect is dissociative and/or hallucinogenic, like with PCP or ketamine, and also a depressant effect (NIDA, 2017b). (We learned about this in a previous module.) Thus, it may not be alcohol content in cough medicine that leads someone to abuse these products (many forms are alcohol free, including tablets and capsules); it may be about the DXM. These medications are often misused in combination with other substances, like alcohol or cannabis (NIDA, 2017b). DXM misuse is largely a young person’s behavior. One reason is that DXM is legal, easily accessible, and relatively inexpensive. Policies have been enacted in many areas requiring purchasers to provide proof that they are over 18 years of age in an effort to curtail adolescent misuse of DXM. Another reason that adolescents might engage in DXM misuse, rather some other substances, is that it may be easier to hide from parents who are unaware that it represents a form of substance misuse.

Cough Medicines. Dextromethorphan (DXM) is an ingredient commonly found in many OTC products intended as a cough suppressant. At recommended doses, DXM works on the part of the brain region that controls coughing. However, at extremely high doses (10-50 times the recommended), it becomes a psychotropic drug causing euphoria (sometimes referred to as “robotripping” or “skittling”—see NIDA, 2017b). The effect is dissociative and/or hallucinogenic, like with PCP or ketamine, and also a depressant effect (NIDA, 2017b). (We learned about this in a previous module.) Thus, it may not be alcohol content in cough medicine that leads someone to abuse these products (many forms are alcohol free, including tablets and capsules); it may be about the DXM. These medications are often misused in combination with other substances, like alcohol or cannabis (NIDA, 2017b). DXM misuse is largely a young person’s behavior. One reason is that DXM is legal, easily accessible, and relatively inexpensive. Policies have been enacted in many areas requiring purchasers to provide proof that they are over 18 years of age in an effort to curtail adolescent misuse of DXM. Another reason that adolescents might engage in DXM misuse, rather some other substances, is that it may be easier to hide from parents who are unaware that it represents a form of substance misuse.

One hazard related to DXM misuse is the potential for acquiring the drug in a highly concentrated form meant for pharmacies to use; this “raw” or “pure” form may easily be taken in much higher doses than intended and usually comes from outside of the U.S. (thus, may not be quality controlled). The risks of DXM misuse include impaired judgment and mental function (thus, impaired driving and risky decisions about engaging in other high risk behaviors), irregular/rapid heart rate, increased blood pressure (increasing the risk of stroke), vomiting (with the risk of aspiration/choking), and coma or death from overdose.

One hazard related to DXM misuse is the potential for acquiring the drug in a highly concentrated form meant for pharmacies to use; this “raw” or “pure” form may easily be taken in much higher doses than intended and usually comes from outside of the U.S. (thus, may not be quality controlled). The risks of DXM misuse include impaired judgment and mental function (thus, impaired driving and risky decisions about engaging in other high risk behaviors), irregular/rapid heart rate, increased blood pressure (increasing the risk of stroke), vomiting (with the risk of aspiration/choking), and coma or death from overdose.

Another hazard lies in using DXM along with other substances. and many formulations that contain DXM also contain other medications, too. For example, OTC cold/flu medications often contain acetaminophen, which can cause liver damage, heart attack, or stroke in overdose amounts. These formulations also may contain antihistamines and other substances intended to relieve cold/flu symptoms and that are dangerous at high doses. If a person is taking enough of the combination medications to “get high,” there may be enough of these other substances to cause irreversible or deadly damage.

Moving beyond the subject of OTC cough medications, many prescription cough medicines include codeine. (We learned about codeine in the module focusing on opioids.) These prescription cough medications may be abused by individuals because codeine shares the same neurotransmitter receptor sites as opioids and heroin. These are potentially addictive medications because of their impact on the increased dopamine released in the brain’s reward system, hence they are Scheduled drugs requiring a prescription for legal distribution.

Weight Loss Aids. You learned about a variety of types of stimulant substances in a previous module, including amphetamines, methamphetamine, cocaine, nicotine, and caffeine. One reason for misuse of stimulant drugs relates to their tendency to suppress appetite, possibly contributing to weight loss. In the past, individuals may have been prescribed stimulant drugs to achieve a weight loss goal. However, this practice has diminished markedly as a result of growing awareness among health care providers of the high addictive potential associated with many stimulant prescription drugs.

There exists a wide range of OTC stimulant products on the market, many with questionable levels of risk and benefit. Until recently banned, OTC products sold in the United States might have included ingredients like ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, ephedra, or phenylpropanolamine. Like other stimulants, these ingredients and others, like bitter orange and ma huang (acting like ephedra), can cause nervousness/anxiety, tremor, rapid/irregular heart rate, increased blood pressure, and stroke, as well as being potentially addictive (Cohen, 2013).

Relatively recently, a new approach to serious weight loss medication has emerged: prescription medications that influence the brain chemistry (serotonin and norepinephrine) of appetite and craving (thus helping reduce caloric intake) without the stimulant effects on heart rate and blood pressure. They largely operate on the serotonin neurotransmitter systems of the brain. These are prescription medications because of their potential risks. Another prescription medication approach works instead on the gastrointestinal (GI) system to reduce fat absorption (thus, calories) from foods consumed.

Anti-diarrheal medication. An OTC opioid medication, loperamide (e.g., Imodium®), has the effect of slowing down the lower GI track, like other opioids. It does not, however, have psychoactive effects at recommended doses since it is designed not to enter the brain (NIDA, 2017b). However, consuming it in large quantity and/or combining it with other substances may cause psychoactive effects experienced with other opioids (NIDA, 2017b); combined with alcohol, the effect of both is amplified (https://www.addictioncenter.com/drugs/over-the-counter-drugs/loperamide-addiction-abuse/). It is unclear whether misuse of loperamide is common (NIDA, 2017b), but may have increased over the past decade in conjunction with the nation’s “opioid epidemic” (https://www.addictioncenter.com/drugs/over-the-counter-drugs/loperamide-addiction-abuse/).

Anti-diarrheal medication. An OTC opioid medication, loperamide (e.g., Imodium®), has the effect of slowing down the lower GI track, like other opioids. It does not, however, have psychoactive effects at recommended doses since it is designed not to enter the brain (NIDA, 2017b). However, consuming it in large quantity and/or combining it with other substances may cause psychoactive effects experienced with other opioids (NIDA, 2017b); combined with alcohol, the effect of both is amplified (https://www.addictioncenter.com/drugs/over-the-counter-drugs/loperamide-addiction-abuse/). It is unclear whether misuse of loperamide is common (NIDA, 2017b), but may have increased over the past decade in conjunction with the nation’s “opioid epidemic” (https://www.addictioncenter.com/drugs/over-the-counter-drugs/loperamide-addiction-abuse/).

What Is Prescription Drug Misuse About?

In earlier modules you learned a bit about the problem of prescription drug misuse—for example, when we learned about opioids, CNS depressants (like benzodiazepine), amphetamines (like Ritalin® and Adderall®), and others. As cannabis becomes increasingly accepted for medicinal use, it too may become a subject of prescription misuse. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA, 2018b) defines prescription drugs as:

“…taking someone else’s prescription, even if for a legitimate medical complaint such as pain; or taking a medication to feel euphoria (i.e., to get high). The term nonmedical use of prescription drugs also refers to these categories of misuse.”

It is difficult to determine the extent to which prescription drug misuse involves engaging in polydrug misuse, either concurrently or sequentially. In other words, an individual may not stick to just one type of substance and may either combine them or move from one to another. As we have discussed elsewhere in this course, the safety of combining prescription, OTC, and/or illicit substances is questionable and depends on the type of substances being combined—they may potentiate (heighten or enhance) each other’s effects and side-effects which increases overdose risks, or one may block the effectiveness of another leading either to a loss of therapeutic advantage of a medically prescribed treatment or a person taking higher doses than safe in order to achieve a desired effect.

It is difficult to determine the extent to which prescription drug misuse involves engaging in polydrug misuse, either concurrently or sequentially. In other words, an individual may not stick to just one type of substance and may either combine them or move from one to another. As we have discussed elsewhere in this course, the safety of combining prescription, OTC, and/or illicit substances is questionable and depends on the type of substances being combined—they may potentiate (heighten or enhance) each other’s effects and side-effects which increases overdose risks, or one may block the effectiveness of another leading either to a loss of therapeutic advantage of a medically prescribed treatment or a person taking higher doses than safe in order to achieve a desired effect.

“Multiple studies have revealed associations between prescription drug misuse and higher rates of cigarette smoking; heavy episodic drinking; and marijuana, cocaine, and other illicit drug use among U.S. adolescents, young adults, and college students” (NIDA, 2018b).

Data from the 2018 NSDUH survey (SAMHSA, 2019) indicate the following regarding past-month prescription drug misuse among individuals aged 12 and older:

- Over 5.4 million (2.0%) are estimated to have engaged in misuse of psychotherapeutic drugs;

- Over 2.8 million (1.0%) engaged in misuse of pain relievers

- Almost 1.7 million (0.6%) engaged in misuse of stimulant drugs

- Almost 1.8 million (0.7%) engaged in misuse of tranquilizers or sedatives (including benzodiazepines).

The demographic breakdown of survey participants indicates that:

- Emerging adults aged 18-25 reported past month pain reliever misuse at higher rates (1.4%) than adults aged 26 and older (1.0%) or adolescents aged 12-17 years (0.6%);

- Emerging adults aged 18-25 reported past month (prescription) stimulant misuse at higher rates (1.7%) than adults aged 26 and older (0.4%) or adolescents aged 12-17 years (0.5%);

- Emerging adults aged 18-25 reported past month tranquilizer or sedative misuse at higher rates (1.2%) than adults aged 26 and older (0.6%) or adolescents aged 12-17 years (0.4%);

- Past month misuse of pain relievers was almost equally divided between men (1.1%) and women (1.0%);

- Misuse of (prescription) stimulants during the past month was somewhat more often reported by men (0.7%) than women (0.5%);

- Tranquilizer or sedative misuse during the past month was reported somewhat more often by men (2.5%) than women (2.2%);

- Misuse of pain relievers during the past month was most commonly reported by individuals self-identifying as being of two or more races (1.4%) or American Indian/Alaska Native (1.4%), slightly less frequently by White (1.1%), Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander (1.1%), Black and African American (1.0%), or Hispanic/Latino (0.9%) individuals, and least often by Asian (0.3%) individuals;

- Past month misuse of (prescription) stimulants was most commonly reported by individuals of two or more races (1.0%), and Asian (0.7%) or White (0.7%) individuals, and less often by individuals self-identifying as Black or African American (0.3%), American Indian/Alaska Native (0.3%), or Hispanic/Latino (0.3%)—no data were provided for Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander individuals;

- Tranquilizer or sedative misuse during the past month was more often reported by individuals of two or more races (3.0%) and those self-identifying as American Indian/Alaska Native (3.0%), White (2.7%), Hispanic/Latino (2.3%), or Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander (2.1%) compared to Black or African American (1.1%) and Asian (0.7%) individuals.

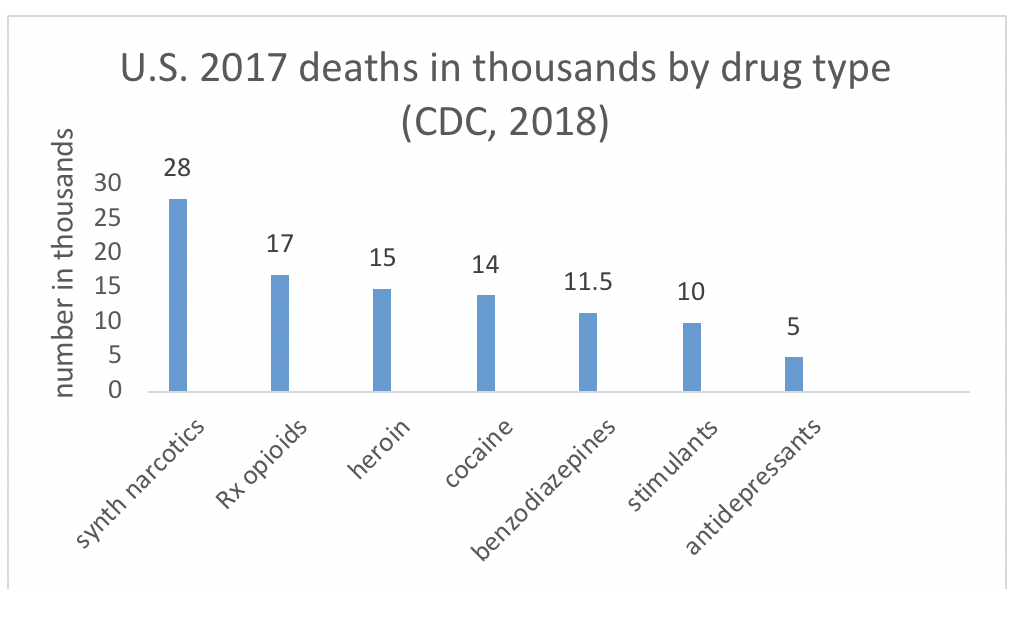

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) produced a report on deaths attributed to drug overdose in the U.S. during 2017 (CDC, 2018). While a great deal of public and policy attention has been directed to the 28,466 deaths reported from fentanyl and other synthetic narcotics (not including methadone), prescription opioids contributed to 17,029 deaths. This is compared to 15,482 deaths from heroin overdose or 13,942 from cocaine. Among the CNS depressants we have studied, benzodiazepines were responsible for 11,537 deaths. On the other hand, 5,269 deaths were from antidepressant overdose and 10,333 from psychostimulants (including methamphetamine). (Not depicted in this chart, note that over 33,000 deaths in 2015 were attributed to alcohol misuse; Lopez, 2016).

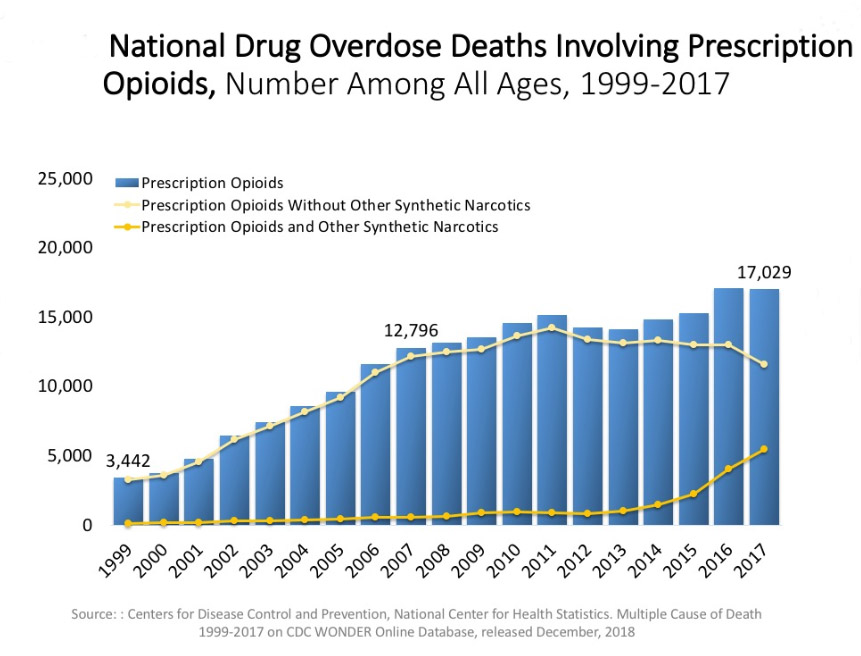

The next chart, produced from a 2018 CDC Wonder report and posted as a series of slides by NIDA (https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates), shows the rate of drug overdose deaths related specifically to prescription opioids from 1999 to 2017. Not only is the change in height of the bars (numbers of deaths in the thousands) showing a dramatic increase, the yellow line across the top dipping down since 2011 and the orange line curving upwards since 2014 show that these prescription opioid deaths increasingly often include other synthetic narcotics (like fentanyl).

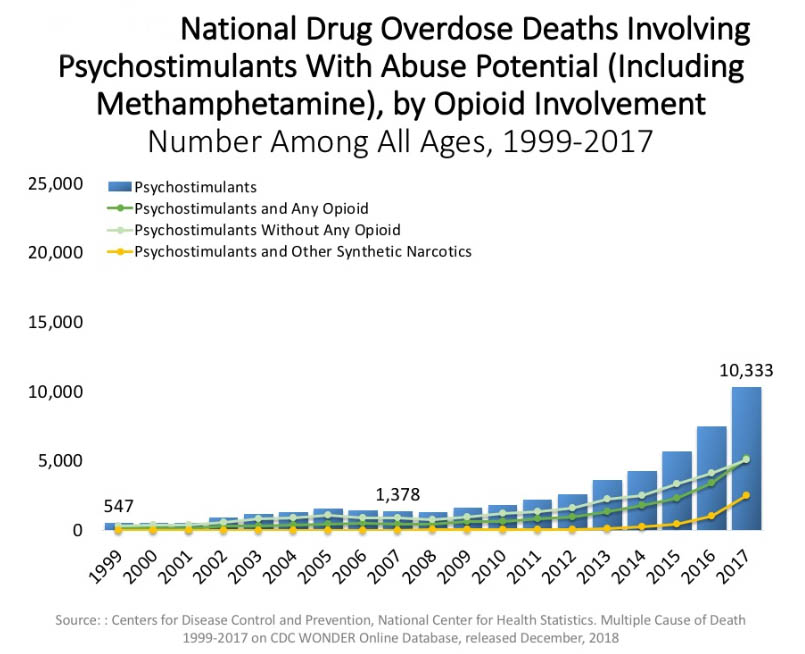

The trend in overdose deaths due to psychostimulants increased even more rapidly over the same time period (including methamphetamine deaths, not only prescription stimulants). The blue bars show the dramatic climb in deaths; the pale green line shows deaths due to psychostimulants alone, and the other two lines show the climb in deaths involving opioids or synthetic narcotics (like fentanyl) in combination with the stimulants.

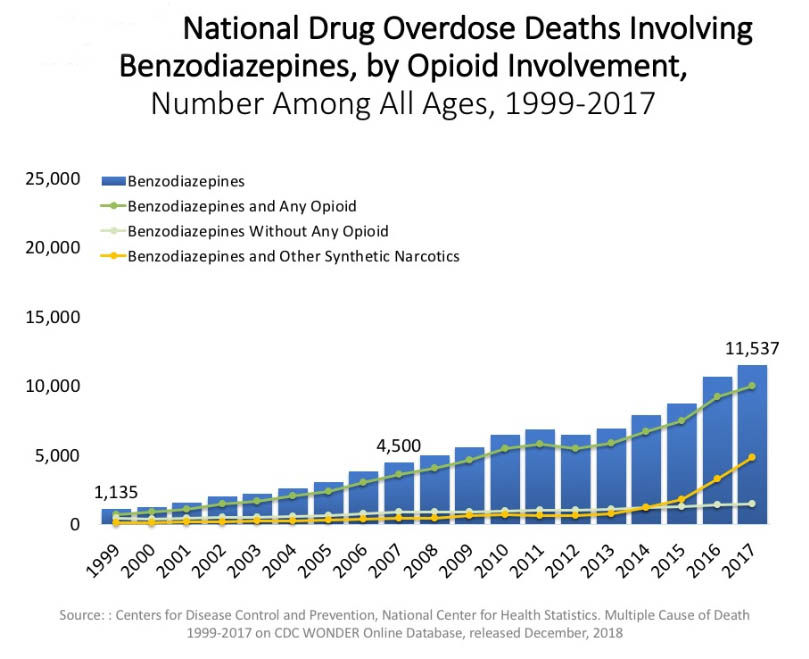

Not to be ignored, as the rates do surpass the stimulant-related deaths, are deaths from benzodiazepine overdose. This graph and the corresponding lines lead to parallel conclusions regarding benzodiazepine deaths over time, including those involving only benzodiazepines and those involving opioids or other synthetic narcotics.

The data do not distinguish between accidental overdose death and suicide by overdose. A review of literature led to the conclusions that: (1) benzodiazepines promote both aggression and impulsivity among individuals who use or misuse them, (2) impulsivity and aggression are both mediators of suicide risk, and (3) there exists a distinct positive correlation, and probably a causal relationship, between prescribed benzodiazepine use and suicide risk (Dodds, 2017). The concern appeared both during the period in which these drugs were used and the period of withdrawal from benzodiazepine use.

Addressing Prescription Drug Misuse

The United Stated Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) produced a report in 2013 containing a list of recommendations for addressing the massive problem of prescription abuse in the United States. Here is a copy of their summarized findings (CDC, 2013):

As described in this report, current HHS prescription drug abuse activities fall within the following eight domains: 1) surveillance, 2) drug abuse prevention, 3) patient and public education, 4) provider education, 5) clinical practice tools, 6) regulatory and oversight activities, 7) drug abuse treatment, and 8) overdose prevention. Each of these areas contributes to ensuring the safe use of prescription drugs and the treatment of prescription drug dependence. Although significant efforts are already underway, a review of current activities along with a review of the prescription drug abuse literature, identified opportunities to enhance policy and programmatic efforts as well as future research are presented. Below are the overarching opportunities to enhance current activities identified in this report.

- Strengthen surveillance systems and capacity

- Build the evidence-base for prescription drug abuse prevention programs

- Enhance coordination of patient, public, and provider education programs among federal agencies

- Further develop targeted patient, public, and provider education programs

- Support efforts to increase provider use of prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs)

- Leverage health information technology to improve clinical care and reduce abuse

- Synthesize pain management guideline recommendations and incorporate into clinical decision support tools

- Collaborate with insurers and pharmacy benefit managers to implement robust claims review programs

- Collaborate with insurers, and pharmacy benefit managers to identify and implement programs that improve oversight of high-risk prescribing.

- Improve analytic tools for regulatory and oversight purposes

- Continue efforts to integrate drug abuse treatment and primary care

- Expand efforts to increase access to medication-assisted treatment

- Expand Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment services

- Prevent opioid overdose through new formulations of naloxone

Described more fully in Section III of the report, the opportunities listed above serve to strengthen programs and policies to reduce prescription drug abuse and overdose in the U.S. HHS has been at the forefront of the response to this serious public health issue and is committed to working with our federal, state, local governmental and non-governmental partners to further the actions included in this report.

You can see from this report that no single, simple solution or strategy will solve the problem of prescription drug misuse. The complex nature of the issues involved dictates applying complex, integrated strategies.

Take a few minutes to conduct a complete inventory of your household:

- What OTC substances are present and what is their potential for misuse by household members or visitors? How might you best secure any that might be problematic? (While you’re at it, check for expiration dates and learn how to dispose of them properly using online resources for your community.)

- What prescription substances are present and what is their potential for misuse by household members or visitors? How might you best secure any that might be problematic? (While you’re at it, check for expiration dates and learn how to dispose of them properly using online resources for your community.)

- What potential inhalants are present and what is their potential for misuse by household members or visitors? How might you best secure any that might be problematic? (While you’re at it, check for expiration dates and learn how to dispose of them properly using online resources for your community.)