Ch. 2: Additional Challenges That Co-occur With Substance Misuse

The topics explored in this chapter are not necessarily distinct from those discussed in the first chapter: they often co-occur in multiples, complicating one another and compounding vulnerability and risk for initiation or worsening of substance misuse, as well as a host of additional physical and mental/behavioral health concerns. In this chapter we focus on a variety of situational circumstances: violence (intimate partner violence, sexual assault, and child maltreatment), employment/unemployment concerns, human trafficking and sex work, housing insecurity, and criminal justice system involvement/incarceration. These issues are often significantly intertwined in a person’s life, along with some of the issues previously discussed (e.g., mental and physical health concerns, violence exposure). For these reasons, scholars recommend substance-related interventions and programs integrate case management into their design to better meet the complex, dynamic needs participants experience (Zweben & West, 2020).

Violence Exposure and Perpetration

Thinking about a person’s exposure to violence or perpetration of violence against others is an example of why it is important to consider the broader range of co-occurring problems rather than limiting attention to comorbid, dual diagnosis, or co-occurring disorders: violence has no diagnostic category, but certainly has a strong relationship to substance misuse. The relative risk of injury related to alcohol use is remarkably greater for intentional injury by someone else (RR=21.50) compared to other sources of alcohol-involved injury, and the odds ratio for violence-related injury increased as a function of amounts of alcohol consumed (WHO, 2009):

| Number of Drinks | Odds Ratio |

| 0 | 1.00 |

| 1 – 2 | 11.14 |

| 3 – 4 | 13.76 |

| 5 or more | 35.57 |

This leads to an examination of the relationship between alcohol or other substance misuse and intimate partner violence, sexual assault, and child maltreatment

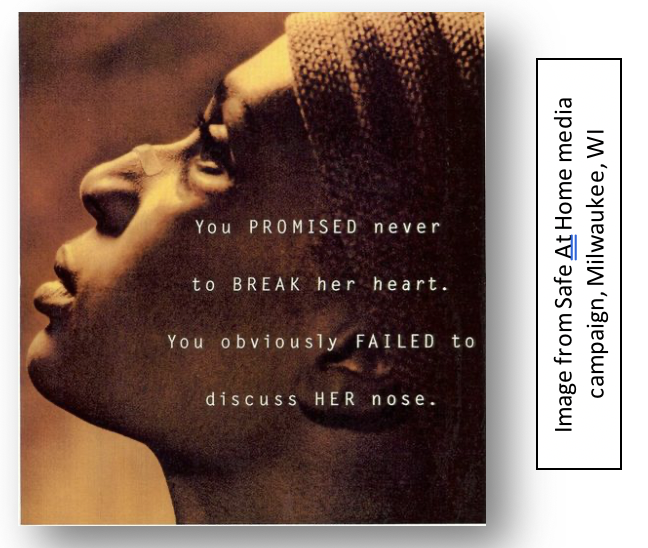

Intimate partner violence. A great deal of evidence indicates that alcohol and other substance misuse are related both to perpetrating and experiencing intimate partner violence (Mengo & Leonard, 2020). On the subject of intimate partner violence (IPV) perpetration, half of men engaged in programs to address their IPV behaviors (“batterer” treatment) also engaged in alcohol or other substance misuse, and half of men with partners who entered substance-related treatment perpetrated IPV events during the past year; furthermore, the two groups of men were 8 or 11 times as likely (respectively) to perpetrate IPV on a day they had been drinking (Bennett & Bland, 2008). Men’s alcohol misuse consistently has been shown to be “one of the most consistent risk factors for IPV” (Mengo & Leonard, 2020, p. 547). Furthermore, “violence is more severe when one or both partners (most often the male partner) has been drinking” (Wilson, Graham, & Taft, 2014, p. 1). Intoxication by or withdrawal from certain substances might increase a person’s overall aggressiveness to anyone in the immediate vicinity, with intimate partners likely being in proximity. Different reviews have specified cocaine and amphetamines/methamphetamine misuse as factors in IPV perpetration, but results are mixed concerning the relationship of IPV with marijuana, sedatives, hallucinogens, and opiates (Begun, 2003; Mengo & Leonard, 2020); withdrawal symptoms from some substances may also be related.

Intimate partner violence. A great deal of evidence indicates that alcohol and other substance misuse are related both to perpetrating and experiencing intimate partner violence (Mengo & Leonard, 2020). On the subject of intimate partner violence (IPV) perpetration, half of men engaged in programs to address their IPV behaviors (“batterer” treatment) also engaged in alcohol or other substance misuse, and half of men with partners who entered substance-related treatment perpetrated IPV events during the past year; furthermore, the two groups of men were 8 or 11 times as likely (respectively) to perpetrate IPV on a day they had been drinking (Bennett & Bland, 2008). Men’s alcohol misuse consistently has been shown to be “one of the most consistent risk factors for IPV” (Mengo & Leonard, 2020, p. 547). Furthermore, “violence is more severe when one or both partners (most often the male partner) has been drinking” (Wilson, Graham, & Taft, 2014, p. 1). Intoxication by or withdrawal from certain substances might increase a person’s overall aggressiveness to anyone in the immediate vicinity, with intimate partners likely being in proximity. Different reviews have specified cocaine and amphetamines/methamphetamine misuse as factors in IPV perpetration, but results are mixed concerning the relationship of IPV with marijuana, sedatives, hallucinogens, and opiates (Begun, 2003; Mengo & Leonard, 2020); withdrawal symptoms from some substances may also be related.

IPV perpetration. Relationships between substance misuse and intimate partner violence (IPV) are complex, and no single mechanism explains it. Possible models related to alcohol or other substance misuse and IPV perpetration include (Begun, 2003; Mengo & Leonard, 2020):

- Certain substances may stimulate biological arousal of a person’s “fight or flight” response which becomes cognitively interpreted as calling for “fight.”

- Alcohol myopia theory specifies that intoxication distorts cognitive interpretation of situations—neutral events may be interpreted as hostile or threatening, dictating an aggressive response that would not be expressed in a sober state.

- Substance use may dampen or suppress a person’s learned inhibitions against acting aggressively (disinhibition).

- Expectancy theory suggests that an individual who believes alcohol (or other substance use) “causes” aggression may use alcohol (or other substances) as an “excuse” for acting aggressively toward others/intimate partners, in anticipation of acting this way.

- An intimate partner may be viewed as interfering with or standing in the way of a person’s access to or use of “needed” substances and/or the couple may argue about the substance misuse.

- Antisocial personality and adults’ antisocial behavior are associated with both substance misuse and perpetration of intimate partner violence—in this model, substance misuse is not a causal factor in perpetrating intimate partner violence but is correlated with it through this third “externalizing” factor.

IPV victimization. In terms of the association between a person’s substance use and being the target of intimate partner violence, substance misuse may have preceded the violence or it may have only developed afterward, in response to the traumatic experience or injuries: “substance use may be a response to the effects of IPV and/or render individuals more vulnerable to ongoing abuse” (Mengo & Leonard, 2020, p. 551). What we explored earlier about trauma/PTSD and “self-medicating” physical or emotional pain/stress apply to this discussion concerning IPV survivors. Having alcohol problems was reported by 29% of women who experienced intimate partner violence, and ¼ to ½ of women receiving IPV victim services also experienced problems with substance misuse (Bailey & Stewart, 2014; Bennett & Bland, 2008). From 55% to 99% of women who experience substance misuse/use disorder also have experienced IPV during their lives (Bennett & Bland, 2008 ).

IPV victimization. In terms of the association between a person’s substance use and being the target of intimate partner violence, substance misuse may have preceded the violence or it may have only developed afterward, in response to the traumatic experience or injuries: “substance use may be a response to the effects of IPV and/or render individuals more vulnerable to ongoing abuse” (Mengo & Leonard, 2020, p. 551). What we explored earlier about trauma/PTSD and “self-medicating” physical or emotional pain/stress apply to this discussion concerning IPV survivors. Having alcohol problems was reported by 29% of women who experienced intimate partner violence, and ¼ to ½ of women receiving IPV victim services also experienced problems with substance misuse (Bailey & Stewart, 2014; Bennett & Bland, 2008). From 55% to 99% of women who experience substance misuse/use disorder also have experienced IPV during their lives (Bennett & Bland, 2008 ).

Intervention. History and data show that if we require a person to successfully complete substance treatment and remain abstinent before engaging them in batterer treatment programming, there is poor follow through: their intimate partners remain at risk for ongoing abuse. On the other hand, it is very difficult to effectively engage a person in the kind of cognitive behavioral interventions commonly employed in programs designed to stop intimate partner violence perpetration: the person’s memory, perceptions, and judgment may remain substance impaired. The current line of thinking is that it is preferable to address both problems simultaneously and integratively, rather than sequentially, but not all communities have this capacity available (Begun, 2003; Mengo & Leonard, 2020). Screening for substance misuse is advised for anyone engaged in IPV interventions—whether they are the perpetrator or survivor. Similarly, anyone engaged in substance-related intervention should be screened for IPV perpetration and/or victimization/survivorship (Mengo & Leonard, 2020).

Sexual violence. As many as 36% of women and 1 in 6 men in the U.S. experienced sexual assault during their lifetimes and “at least 50% of sexual assaults involved alcohol consumption by the victim, perpetrator, or both” (Davis, Kirwan, Neilson, & Stappenbeck, 2020, p. 561). Alcohol or other substances may be consumed either voluntarily or involuntarily—when a perpetrator administers them to a victim (e.g. “date rape” drugs). Either way, a sexual assault victim may be severely intoxicated, incapacitated, unconscious, or otherwise unable to consent—these are termed incapacitated or alcohol/drug facilitated sexual assaults or rapes (Davis et al., 2020). Drinking settings are relevant in that the majority of alcohol-involved sexual assaults occur either around bar and party contexts (Cleveland, Testa, & Hone, 2019) or within the context of intimate partner relationships; much less is known about drug-involved sexual assault (Davis et al, 2020).

Among college men, those with higher bar and party attendance had a greater probability of perpetrating sexual assault than other college men, particularly when they engage in greater number of “hook ups” (Testa & Cleveland, 2017). Alcohol-involved sexual assaults often are of a more severe form, with assault severity increasing as alcohol consumption increases, up to the point of heavy intoxication, and often have more severe outcomes than assaults not involving alcohol (Davis et al., 2020; Testa, Vanzile-Tamsen & Livingston, 2004). Sex-related alcohol expectancies, increased impulsivity/disinhibition, slowed information processing/situational interpretation, and generally increased inappropriate behavior/aggression may play a significant role in sexual assault perpetration (Davis et al., 2020; Pegram et al., 2018). The alcohol myopia theory previously described regarding IPV may also be relevant to sexual assault perpetration and tendency to ignore or misinterpret the victim’s social cues (Davis et al., 2020).

Among college men, those with higher bar and party attendance had a greater probability of perpetrating sexual assault than other college men, particularly when they engage in greater number of “hook ups” (Testa & Cleveland, 2017). Alcohol-involved sexual assaults often are of a more severe form, with assault severity increasing as alcohol consumption increases, up to the point of heavy intoxication, and often have more severe outcomes than assaults not involving alcohol (Davis et al., 2020; Testa, Vanzile-Tamsen & Livingston, 2004). Sex-related alcohol expectancies, increased impulsivity/disinhibition, slowed information processing/situational interpretation, and generally increased inappropriate behavior/aggression may play a significant role in sexual assault perpetration (Davis et al., 2020; Pegram et al., 2018). The alcohol myopia theory previously described regarding IPV may also be relevant to sexual assault perpetration and tendency to ignore or misinterpret the victim’s social cues (Davis et al., 2020).

Heavy drinking in bar/party settings place a woman in a context where sexual assault is more common, and “being intoxicated can impair a victim’s ability to mitigate or thwart an attempted sexual assault” (Davis et al., 2020, p. 565). Heavy intoxication increases the risk of penetrating sexual assault (Testa et al, 2004); among college women, “heavy episodic drinking (HED) increases risk for sexual assault victimization, particularly incapacitated rape” (Testa & Cleveland, 2017). Intoxication may diminish a person’s sexual assault risk assessment (Melkonian & Ham, 2018) and increase self-blame for an experienced assault (Norris, Zawacki, Davis, & George, 2018). The fallout from sexual assault victimization can be traumatic—prior discussions of trauma and PTSD are applicable—and may involve physical as well as significant mental health and social relationship consequences. “Women with sexual assault histories may consume alcohol in part to regulate emotional distress and cope with negative affect states” (Davis, et al., 2020, p. 566). Thus, alcohol and other substance misuse may precede, follow, or both precede and follow a sexual assault experience.

Sexual assault prevention interventions include risk reduction programs—preparing potentially vulnerable individuals with protective behavior strategies, situational awareness, and self-defense skills, as well as efforts to change community norms surrounding violence against women (Davis et al., 2020). Prevention programs may be designed to intervene with potential perpetrators of sexual assault or to increase bystander awareness and willingness to intervene. Both types of prevention programs too rarely include information about alcohol or other drug involvement (Davis et al., 2020).

Sexual assault prevention interventions include risk reduction programs—preparing potentially vulnerable individuals with protective behavior strategies, situational awareness, and self-defense skills, as well as efforts to change community norms surrounding violence against women (Davis et al., 2020). Prevention programs may be designed to intervene with potential perpetrators of sexual assault or to increase bystander awareness and willingness to intervene. Both types of prevention programs too rarely include information about alcohol or other drug involvement (Davis et al., 2020).

Child maltreatment/neglect. Many individuals engaged in alcohol or other substance misuse are parents or primary caregivers to children or adolescents, and vice versa, over 12% of children under the age of 18 years (over 8.7 million) live with at least one parent experiencing a substance use disorder (Straussner & Fewell, 2020). These children are at greater risk for neurological, psychological, developmental, and behavioral problems, as well for experiencing some form of child maltreatment (Straussner & Fewell, 2020). Additionally, they may live under conditions of dysfunctional family dynamics, housing, food, and economic instability, and/or unstable legal and custody status.

Child maltreatment/neglect. Many individuals engaged in alcohol or other substance misuse are parents or primary caregivers to children or adolescents, and vice versa, over 12% of children under the age of 18 years (over 8.7 million) live with at least one parent experiencing a substance use disorder (Straussner & Fewell, 2020). These children are at greater risk for neurological, psychological, developmental, and behavioral problems, as well for experiencing some form of child maltreatment (Straussner & Fewell, 2020). Additionally, they may live under conditions of dysfunctional family dynamics, housing, food, and economic instability, and/or unstable legal and custody status.

Estimates of the proportion of child welfare cases involving parental substance misuse range from 34% to 78% and include harms on a continuum, from a parent’s inability to function to children’s exposure to violence, hazardous environments, and substances (Kepple & Freisthler, 2020). For example, accidental ingestion of drugs leads to a high number of emergency department visits for children, especially among children aged 5 years or under (SAMHSA, 2013). Children are at risk when a parent is intoxicated, experiencing substance withdrawal, or engaging in the illicit manufacture or distribution of substances (Kepple & Freisthler, 2020). Neglectful parenting is generally more common than physical violence: among children who experienced maltreatment in 2015, neglect represented 75% of the cases, 17.2% involved physical abuse, and 8.4% involved sexual abuse (National Children’s Alliance, https://www.nationalchildrensalliance.org/media-room/nca-digital-media-kit/national-statistics-on-child-abuse/).

A parent or caregiver engaged in substance misuse may spend long periods of time unaware of or unresponsive to a child’s needs for food, protection, cognitive and language stimulation, discipline and guidance, comfort, health care, school attendance, supervision, and other critical developmental needs. Furthermore, resources that could be used to meet a child’s basic needs may be spent instead on substances. Harm may befall a child exposed to substance residue in their physical environment, or a child having access to alcohol, tobacco, or other substances with or without a parent’s knowledge/approval. A parent’s illegal dealing in drugs may involve a child’s exposure to weapons and threats of or witnessing violence. Some children also experience exploitation as they are enlisted by a parent in drug deals or other aspects of a lifestyle involving illegal substance activities.

A parent or caregiver engaged in substance misuse may spend long periods of time unaware of or unresponsive to a child’s needs for food, protection, cognitive and language stimulation, discipline and guidance, comfort, health care, school attendance, supervision, and other critical developmental needs. Furthermore, resources that could be used to meet a child’s basic needs may be spent instead on substances. Harm may befall a child exposed to substance residue in their physical environment, or a child having access to alcohol, tobacco, or other substances with or without a parent’s knowledge/approval. A parent’s illegal dealing in drugs may involve a child’s exposure to weapons and threats of or witnessing violence. Some children also experience exploitation as they are enlisted by a parent in drug deals or other aspects of a lifestyle involving illegal substance activities.

Among the physical, developmental, emotional and other harms resulting from child maltreatment, early drinking onset (preteen) was identified as three times more common among adolescents who had experienced one or more types of maltreatment, and 54% of adolescents who had experienced sexual abused engaged in substance misuse (Bailey & Stewart, 2014). The potential child maltreatment risks and harms are not equal across different types of substances; they differ somewhat by type of substance and how substances are misused (Kepple & Freisthler, 2020). It is important for anyone working in the field of substance-related treatment to learn how to recognize signs of child maltreatment, including neglect, and understand what they are legally obligated to do when it is suspected (i.e. mandated reporting policy and procedures).

Employment Concerns

Heavy and frequent alcohol or other substance misuse prior to or during work hours poses significant employment problems, including absenteeism and frequent job changes (Bush & Lipari, 2015), as well as the potential for workplace accidents and injuries. In the U.S., the vast majority (70%) of individuals who engage in heavy drinking or other substance misuse are employed full time; however, this information does not inform us about the proportion of individuals in the workforce who engage in these addictive behaviors (Frone, 2012). Based on various national surveys, Frone (2012) concluded that 8.5% to 9.3% of workers frequently engaged in heavy drinking, 4.6 million workers (3.6%) frequently drank to intoxication, and 9.3% of the workforce (12 million workers) may experience an alcohol use disorder. Additionally, 81 million workers (6.3%) frequently engaged in illicit substance use, 3.5% of the workforce (4.5 million workers) frequently were intoxicated from use of an illicit substance, and 2.0% of the workforce (2.6 million workers) may experience a substance use disorder involving illicit substances. Cannabis/marijuana was the illicit substance most commonly used. More difficult to determine is the prevalence of alcohol or other substance misuse just prior to working or during the work period; Frone (2012) concluded that 13 million workers (over 10%) experienced impairment in the workplace from alcohol intoxication or (most frequently) hangover, and 1 million of them did so frequently. Additionally, almost 2 million workers (1.5%) frequently used illicit substances within 2 hours prior to work and 1.8 million (1.4%) frequently used illicit drugs during work.

These figures are inconsistently distributed across job types. In 2008-2012 NSDUH data, Bush and Lipari (2015) indicated that past month heavy alcohol use was reported at the highest rates by workers in mining (17.5%) and construction (16.5%) industries, followed by accommodations and food services workers (11.8%), and those in arts, entertainment, and recreation (11.5%); the rate was lowest among those working in health care and social assistance (4.4%) or educational services (4.7%). Past month use of illicit substances was greatest among workers in accommodations and food service industries (19.1%) or arts, entertainment, and recreation (13.7%); the rate was lowest among workers in public administration (4.3%), educational services (4.8%), mining (5.0%), or health and social assistance (5.5%). Not surprising, based on these patterns, past year substance use disorder was greatest among workers in accommodations and food services (16.9%), construction (14.3%), arts/entertainment/recreation (12.9%), and mining (11.8%).

The issue of substance misuse and employment has two important sides: protecting the workplace and protecting the worker. To the first, many employers and companies have posted policies concerning alcohol or other substance use, whether including nicotine or not—zero tolerance policies, for example. This approach may be combined with drug testing policies and programs of testing, as well as an employee assistance program (EAP) or services made available to individual employees experiencing substance-related (or other mental/behavioral health) problems (Hall, 2020). A few barriers to implementing these strategies exist, especially for small businesses: the cost of drug testing materials, questionable accuracy of the tests used, legal concerns related to drug searches, privacy issues related to use of EAP services, and costs of providing EAP services. While these issues are often thought about in relation to manufacturing and retail settings, they should be considered in terms of workplaces where an individual is responsible for driving (or flying), for the welfare of children or adults needing care, carrying weapons, and making decisions that affect others’ health, safety, and well-being.

The issue of substance misuse and employment has two important sides: protecting the workplace and protecting the worker. To the first, many employers and companies have posted policies concerning alcohol or other substance use, whether including nicotine or not—zero tolerance policies, for example. This approach may be combined with drug testing policies and programs of testing, as well as an employee assistance program (EAP) or services made available to individual employees experiencing substance-related (or other mental/behavioral health) problems (Hall, 2020). A few barriers to implementing these strategies exist, especially for small businesses: the cost of drug testing materials, questionable accuracy of the tests used, legal concerns related to drug searches, privacy issues related to use of EAP services, and costs of providing EAP services. While these issues are often thought about in relation to manufacturing and retail settings, they should be considered in terms of workplaces where an individual is responsible for driving (or flying), for the welfare of children or adults needing care, carrying weapons, and making decisions that affect others’ health, safety, and well-being.

On the employee side, substance misuse may contribute to loss of employment, unemployment, and underemployment. Among persons who were unemployed in 2011, past month use of illicit substances was reported by about 17%: a rate more than double what it was among persons employed full time and almost double the rate among persons employed part time (Badel & Greaney, 2013). Marijuana was, by far, the most common (15% of unemployed persons) and illegally acquired pain relievers were second (just under 5% of unemployed persons). Whether the unemployment was caused by or led to substance misuse is difficult to unravel; it is also possible that other factors contributed to both (e.g. the Great Recession having a greater impact on a class of workers who already engaged in substance misuse at a greater rate).

Sex Work, Human Trafficking, and Exploitation

“A commonly held view is that women engage in street-level prostitution to obtain money to buy drugs or in direct exchange for drugs. Indeed, existing research demonstrates a strong association between substance abuse and prostitution…The substances that women in prostitution most commonly abuse are heroin, cocaine (crack), marijuana, and alcohol” (Wiechelt & Shdaimah, 2011, p. 161). Substance misuse may precede involvement in prostitution, to fund their substance use and the “degradation and trauma involved in prostitution” may worsen a pre-existing substance use disorder (Wiechelt & Shdaimah, 2011, p. 162). On the other hand, substance misuse may begin after initiation of prostitution, as alcohol and other substance use “appear to make women in prostitution feel more confident and able to manage their interactions with their “customers” as well as provide them with a mechanism for coping with or numbing their negative feelings” (Wiechelt & Shdaimah, 2011, p. 161). Either model alone is insufficient as they “fail to capture the cascade of factors” involved in the co-occurrence of sex work and substance misuse (Wiechelt & Shdaimah, 2011, p. 162).

Women, men, children, and adolescents engaging in sex work seldom do so voluntarily—typically, a high degree of coercion and abuse is involved. Globally, human trafficking occurs as forced work in agriculture, fishing, manufacturing, mining, forestry, construction, domestic/cleaning, and hospitality service labor sectors, with others forced to serve as beggars, soldiers, “wives” and sex workers (WHO, 2012). This is happening around the world to female and male children, adolescents, and adults. The United Nations defined human trafficking is as follows (WHO, 2012):

[T]he recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, or abduction, or fraud, or deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation.

Exploitation is a key concept involved in the intersection between substance misuse and human trafficking for sex/sex work. Because human trafficking and sex work are generally illegal, they are somewhat invisible in nature, making it difficult to generate accurate data on prevalence. The invisibility also contributes to difficulties in providing for individuals who are trafficked—ensuring that basic needs are adequately met, much less their health, mental health, and protection needs. These children, women, and men:

“…may encounter psychological, physical and/or sexual abuse; forced or coerced use of drugs or alcohol; social restrictions and emotional manipulation; economic exploitation, inescapable debts; and legal insecurities…Risks often persist even after a person is released from the trafficking situation, and only a small proportion of people reach post-trafficking services or receive any financial or other compensation” (WHO, 2012).

Alcohol and other drugs are frequently involved with human trafficking—either used to control a person already experiencing substance use disorder, used to coerce someone to initiate use, and/or used to cope with the physical and psychological traumas associated with trafficking (WHO, 2012). Anecdotal cases exist where family members allowed the sexual exploitation/human trafficking of their children by others in exchange for drugs or drug money (Keely, 2020). Among over 23,000 callers to the National Human Trafficking Hotline and Resource Center, substance use was one of the top five risk factors for falling prey to traffickers (https://humantraffickinghotline.org/sites/default/files/Polaris_National_Hotline_2018_Statistics_Fact_Sheet.pdf). In the state of Ohio, induced substance abuse was a significant control method reported to the national hotline, and discovered through criminal investigations, drugs were frequently used as a means of coercion (Roberson, n.d.). Coercion efforts used to compel victims included threatening to call victims’ probation officer to report their drug use, creating a debt (fictitious), threats or anticipation of withdrawal sickness, and payment for “services” in drugs—in other words, exploiting a person’s addiction.

Recovery advocates recommend supportive services for victims of human trafficking, rather than imposing criminal justice system sanctions. In a qualitative arts-based study of women engaged in prostitution, investigators concluded: “A combination of systemic violence, poverty, ill health, addiction, and prostitution shaped the lives and circumstances of the women in our sample, all of whom described a longing for basic health, security, belonging, and stability” (Shdaimah & Wiechelt, 2017, p. 362). They reported that women “engaged largely in what is often called “survival” sex work; their motivation for engaging in prostitution is to meet their basic needs of shelter, clothing, food, and, often, addiction” (Shdaimah & Wiechelt, 2017, p. 363). Trauma-based and trauma-informed care is in order (Shdaimah & Wiechelt, 2011), potentially delivered within the structure of diversionary treatment-based and specialty drug court programs rather than through traditional criminal justice punitive responses (Begun & Clark-Hammond, 2012).

Housing Insecurity

That alcohol or other substance misuse leads to homelessness has been a long-standing stereotype in the U.S., much of which has an underlying morality theme. However, evidence more accurately suggests that the causal relationships are much more complex, particular in terms of multiple co-occurring phenomena being inter-twined: housing instability/insecurity, mental health issues, physical health issues, intimate partner/family violence, economics of poverty, discrimination, and alcohol or other substance misuse (Pynoos, Schafer, & Hartman, 2017). Recognizing that homelessness is a dynamic state, the issue is more appropriately considered under the rubric of housing instability/stability and security over time. Housing stability, with reliable and safe shelter, is important in providing substance-related and recovery support services over time, services that persist across transitions in how/where a person is living. Not only does housing stability affect a person’s engagement in substance-related intervention, substance misuse may interfere with a person’s housing stability. For example, public housing services may have policies that preclude a person engaged in substance misuse from housing assistance eligibility, and landlords or family/friends may refuse to house someone who is engaging in substance misuse.

That alcohol or other substance misuse leads to homelessness has been a long-standing stereotype in the U.S., much of which has an underlying morality theme. However, evidence more accurately suggests that the causal relationships are much more complex, particular in terms of multiple co-occurring phenomena being inter-twined: housing instability/insecurity, mental health issues, physical health issues, intimate partner/family violence, economics of poverty, discrimination, and alcohol or other substance misuse (Pynoos, Schafer, & Hartman, 2017). Recognizing that homelessness is a dynamic state, the issue is more appropriately considered under the rubric of housing instability/stability and security over time. Housing stability, with reliable and safe shelter, is important in providing substance-related and recovery support services over time, services that persist across transitions in how/where a person is living. Not only does housing stability affect a person’s engagement in substance-related intervention, substance misuse may interfere with a person’s housing stability. For example, public housing services may have policies that preclude a person engaged in substance misuse from housing assistance eligibility, and landlords or family/friends may refuse to house someone who is engaging in substance misuse.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) recommends engaging in community-based service responses that place housing at the top of the service provision priority list and deliver Permanent Supportive Housing, Housing First, and Recovery Housing service strategies (SAMHSA, 2019b). The goal is to help meet individuals’ recovery support needs with stable housing where case management and wraparound care are easily accessible in substance-free environments involving peer support and other recovery support.

Incarceration and Other Criminal Justice Involvement

Much of what surrounds alcohol and other substance misuse involves illegal behaviors, thus there exists a high degree of co-occurrence between substance misuse and criminal justice system involvement—including courts, incarceration in jail, prison, and correctional treatment settings. Criminal activities may include possession and/or distribution offenses, offenses committed in order to obtain substances, and offenses committed while intoxicated or in withdrawal from substance misuse. For these reasons, substance misuse is termed a criminogenic factor, meaning that it contributes to the rate at which criminal offenses are committed. According to a Bureau of Justice Statistics report (Sawyer, 2017), in the U.S. between 2007-2009:

- 21% of persons sentenced to state prisons and local jails were incarcerated for crimes committed to obtain drugs or money for drugs;

- 40% of individuals incarcerated for property crimes committed those crimes for drug-related reasons;

- 14% of individuals incarcerated for violent crimes committed those crimes for drug-related reasons;

- about 40% of sentenced incarcerated persons reported using drugs at the time of the offense for which they were in jail or state prison;

- more than 50% of persons in state prisons and 66% sentenced to jail experienced substance use disorders;

- only about 25% of incarcerated individuals experiencing substance use disorders received substance-related treatment while in jail or state prison.

Others report that an estimated 75% of jail and prison inmates need intervention for substance misuse or substance use disorder, but only about 11% receive these services during their period of incarceration (Pettus-Davis & Epperson, 2015). It is of great concern that a population in great need lacks access to evidence-supported substance-related interventions during incarceration and as they transition to community living post-release (Begun, Rose, & LeBel, 2011). While the majority of incarcerated adults are men, the statistics concerning substance-involvement and women warrant attention as they do paint a somewhat more dire picture: an estimated 20% of incarcerated women meet criteria for alcohol use disorder and 51% for substance use disorder; this is compared to 30% of incarcerated men (Rose & LeBel, 2020).

Others report that an estimated 75% of jail and prison inmates need intervention for substance misuse or substance use disorder, but only about 11% receive these services during their period of incarceration (Pettus-Davis & Epperson, 2015). It is of great concern that a population in great need lacks access to evidence-supported substance-related interventions during incarceration and as they transition to community living post-release (Begun, Rose, & LeBel, 2011). While the majority of incarcerated adults are men, the statistics concerning substance-involvement and women warrant attention as they do paint a somewhat more dire picture: an estimated 20% of incarcerated women meet criteria for alcohol use disorder and 51% for substance use disorder; this is compared to 30% of incarcerated men (Rose & LeBel, 2020).

Why does all of this matter? First, it suggests that incarceration may provide particularly salient “teachable moments” related to substance misuse. In a randomized control study conducted with women in jail preparing for community reentry, investigators reported a significantly greater reduction in post-release alcohol and other drug use scores among women provided with screening and brief intervention near the end of their incarceration compared to women receiving treatment as usual—which meant little to no intervention preparing them to address their problems with alcohol and other substances (Begun, Rose, & LeBel, 2011). Surprisingly, this difference in improvement was not attributed to post-release treatment engagement as many women in both groups were unable to access substance-related treatment; the treatment preparation alone was a meaningful intervention.

Why does all of this matter? First, it suggests that incarceration may provide particularly salient “teachable moments” related to substance misuse. In a randomized control study conducted with women in jail preparing for community reentry, investigators reported a significantly greater reduction in post-release alcohol and other drug use scores among women provided with screening and brief intervention near the end of their incarceration compared to women receiving treatment as usual—which meant little to no intervention preparing them to address their problems with alcohol and other substances (Begun, Rose, & LeBel, 2011). Surprisingly, this difference in improvement was not attributed to post-release treatment engagement as many women in both groups were unable to access substance-related treatment; the treatment preparation alone was a meaningful intervention.

Second, it is critical to ensure strong transitional support as a person is released to the community, supporting them in maintaining recovery gains out in the community. This transition can be extremely difficult for individuals to manage as there are often problems with gaining secure housing, becoming employed in work that provides a sustaining wage, and access to needed health, mental health, and addiction services. In the previously described study involving women released from jail, the most common barriers to utilizing alcohol or other drug treatment services as: perceiving that treatment programs were full, inability to pay for treatment/no health insurance coverage for treatment, and a lack of transportation to treatment (Begun, Rose, & LeBel, 2011). A pre-/post-release study involving men and women incarcerated in Ohio’s jails, state prisons, and community based correctional facilities (CBCFs, treatment providing residential programs during final months of incarceration) reported that 44% of individuals experienced the need for services to help them address their problems with substance misuse and the most significant barrier to receiving such services was inability to pay (Begun, Early, & Hodge, 2016). Substance misuse is a major driving factor in the return to incarceration, suggesting that a failure to address the problem initially has long-lasting implications for recurrence and re-offending (Rose & LeBel, 2020).

Second, it is critical to ensure strong transitional support as a person is released to the community, supporting them in maintaining recovery gains out in the community. This transition can be extremely difficult for individuals to manage as there are often problems with gaining secure housing, becoming employed in work that provides a sustaining wage, and access to needed health, mental health, and addiction services. In the previously described study involving women released from jail, the most common barriers to utilizing alcohol or other drug treatment services as: perceiving that treatment programs were full, inability to pay for treatment/no health insurance coverage for treatment, and a lack of transportation to treatment (Begun, Rose, & LeBel, 2011). A pre-/post-release study involving men and women incarcerated in Ohio’s jails, state prisons, and community based correctional facilities (CBCFs, treatment providing residential programs during final months of incarceration) reported that 44% of individuals experienced the need for services to help them address their problems with substance misuse and the most significant barrier to receiving such services was inability to pay (Begun, Early, & Hodge, 2016). Substance misuse is a major driving factor in the return to incarceration, suggesting that a failure to address the problem initially has long-lasting implications for recurrence and re-offending (Rose & LeBel, 2020).

Third, addressing substance-related problems, and especially changing the criminal justice response to non-violent substance-related offending are consistent themes in a “smart decarceration” movement (Pettus-Davis & Epperson, 2015; Epperson & Pettus-Davis, 2017). As you learned in the beginning of our course, the War on Drugs has driven a great deal of policy concerning responses to substance use/misuse across the nation. Smart decarceration is about reversing the nation’s nearly 40-year mass incarceration trend, as it has proven to be unsustainable and harmful to individuals, families, communities, and society alike, as well as perpetuating historical class and race disparities (Epperson & Pettus-Davis, 2017)). While you might be thinking that failing to stop drug trafficking through criminal justice responses would be unwise, it is important to recognize that globally, among individuals serving sentences for drug offenses, over 80% are serving sentences involving drug possession for personal use (Rose & LeBel, 2020). The introduction of drug courts, beginning in 1989, represents an evidence-supported, integrated criminal justice system and drug treatment response (Lloyd & Fendrich, 2020). Drug courts offer as mandated treatment involvement with close case monitoring as an alternative to incarceration (Lloyd & Fendrich, 2020). Thus, evidence-supported and evidence-based interventions do exist for supporting recovery from substance misuse/use disorder among men and women while incarcerated and during community reentry; policy and funding changes are needed to more fully support their implementation (Epperson & Pettus-Davis, 2017; Rose & LeBel, 2020).

Third, addressing substance-related problems, and especially changing the criminal justice response to non-violent substance-related offending are consistent themes in a “smart decarceration” movement (Pettus-Davis & Epperson, 2015; Epperson & Pettus-Davis, 2017). As you learned in the beginning of our course, the War on Drugs has driven a great deal of policy concerning responses to substance use/misuse across the nation. Smart decarceration is about reversing the nation’s nearly 40-year mass incarceration trend, as it has proven to be unsustainable and harmful to individuals, families, communities, and society alike, as well as perpetuating historical class and race disparities (Epperson & Pettus-Davis, 2017)). While you might be thinking that failing to stop drug trafficking through criminal justice responses would be unwise, it is important to recognize that globally, among individuals serving sentences for drug offenses, over 80% are serving sentences involving drug possession for personal use (Rose & LeBel, 2020). The introduction of drug courts, beginning in 1989, represents an evidence-supported, integrated criminal justice system and drug treatment response (Lloyd & Fendrich, 2020). Drug courts offer as mandated treatment involvement with close case monitoring as an alternative to incarceration (Lloyd & Fendrich, 2020). Thus, evidence-supported and evidence-based interventions do exist for supporting recovery from substance misuse/use disorder among men and women while incarcerated and during community reentry; policy and funding changes are needed to more fully support their implementation (Epperson & Pettus-Davis, 2017; Rose & LeBel, 2020).

STOP & THINK

A Perfect Storm: After completing these two chapters concerned with co-occurring mental, physical, and situational challenges, think about the following situation and its implications for understanding and intervening around substance misuse. In late 2019 and early 2020 the world awoke to a global pandemic: COVID-19 is a potentially serious, even deadly, disease communicated through saliva or “droplets” containing a corona virus. The population of individuals engaged in substance misuse and experiencing substance use disorders may be at particularly high risk for exposure to the virus, contracting the COVID-19 disease, and having poor outcomes if they do become ill.

Based on what you read in these chapters, what might you expect in terms of the following and why?

- Disease transmission among individuals who engage in “party” or other group alcohol or cannabis consumption.

- Likelihood of successful “social distancing” and disease containment within communities of individuals engaging in substance misuse–consider mental status, health disparities, behavior, life circumstances on a broad level (e.g. what kind of work they may be engaged in, housing, incarceration, and more of the topics discussed in chapter 2).

- Recovery support when health and mental health providers were scrambling to adapt to the pandemic and unstable/unreliable availability of many medications (including those used in pharmacotherapy for mental and substance use disorders).

- Likelihood of more severe outcomes from infection with the COVID-19 virus (e.g., consider the range of physical health concerns explored in chapter 1).

What would you have recommended to public health officials and human services providers with regard to this corona virus/COVID-19 pandemic among members of these communities?

Module 13 Summary

In this module you explored a host of issues, concerns, and problems that commonly co-occur with substance misuse and substance use disorder. First, we looked into diagnosable comorbid conditions of mind and body. The mental disorders reviewed include anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, dementia, personality disorders, impulse disorder/ADD/ADHD,

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and gambling disorder. Next, we turned our attention to the physical conditions of concern, including both communicable and non-communicable diseases, as well as traumatic brain and other injuries. That section also included content related to driving under the influence of alcohol and other substances. The following chapter explored some situational contexts that often co-occur with substance misuse: violence (including intimate partner violence, child maltreatment, and sexual assault), employment and unemployment concerns, sex work/human trafficking and related exploitation, housing insecurity, and criminal justice involvement or incarceration in jails or prison.

A common theme throughout this module is the complex nature of the relationships between co-occurring phenomena—that one may cause the other, the other way around may happen, both may be caused by a third factor, or they may interact in an iterative manner over time. Nonetheless, co-occurring problems do have an effect on severity, outcomes, and intervention. In most cases, it is recommended that screening and assessment include their consideration, and that they may best be treated in an integrative approach rather than either sequentially or in a disconnected concurrent manner. At this point, you are prepared to review key terms introduced in this module, and to proceed to the course conclusion chapter.