7 Options

Develop a range of options for adding to, removing, combining, transforming, and explaining the contested symbols, as well as creative ways to establish interactive spaces, possibly including plans for changes unrelated to symbols.

POSSIBLE STRATEGIES

Keeping in mind community goals regarding the environment, identify symbols and public spaces with the potential to serve these goals, by themselves or in combination with other changes and stakeholder involvement.

Think broadly about what might affect how people experience their environment including holidays, festivals, parades, ceremonies, music, food served at public events, pictures on university websites, events on a holy day for members of a particular religion or ethnicity, rituals such as battle reenactments, who lives in college dormitories, and art. The ritual context in which symbols are used is central to understanding meaning and changes in meaning.

Anticipate the ways people will feel threatened by change so that the planning can weigh the needs of these individuals.

Examine existing symbols that work against the identified goals or that might lead to conflicts because of advocacy regarding national or local issues.

Consider what other steps, such as storytelling or policy changes, might be combined with the symbols strategy to help achieve the community’s goals.

Identify the ways in which there is tension among the goals served by each option, such as approaches that make people comfortable to engage while at the same time protecting people from insults and threats.

Consider ways to allow future modification, such as temporary exhibits or policies that facilitate changes over time.

IN MORE DETAIL

Generating multiple options and discussing them with community members and experts (as discussed in Selection and Participation of a Planning Group and Symbols Experts) increases the chances of settling on a symbols approach that meets multiple interests. A multiple-option approach also encourages the kind of deliberation that promotes understanding across societal divides. This process can help identify potential opposition to any additions or modifications of symbols, so that the potential backlash can be weighed in the choice of options.

By combining both symbol and non-symbol options, planners can gauge the degree to which that combination serves their goals. The combined approach may be particularly helpful when a group has demanded the relocation of a symbol to achieve something visible because they perceive that visible change may keep up the momentum to achieve other, more important long-term goals. If deep changes can be implemented in the short term, the group may be open to a different symbol-based strategy, one that might honor the interests of yet other groups.

To begin the option creation, staff for the planning group might suggest a series of discussion questions. Questions to encourage the group to think of options that make positive contributions toward achieving goals might include, depending on the community or campus goals:

- What new or modified ritual or other symbol would help the whole community understand something currently important to part of the community, make part of the community feel valued, or instead provide a way for the community to grieve or celebrate together?

- Would commemorating difficult pasts with current effects (e.g., discrimination that reduced wealth for descendants) facilitate change?

- Would a new symbol promote understanding across the community’s fault lines or feel welcoming to a broader base of people?

- Could a symbol lead to a transformative shift in how people understand history, and thus their determination not to repeat the errors?

To anticipate how existing symbols might undermine community goals or are resented by members of the community, focus on the present and future. Questions to spur discussion might include:

- Do the symbols honor persons whose accomplishments required the oppression of others?

- Do the symbols encapsulate narratives of history while omitting the difficult, painful, and shameful parts that continue to affect persons in the present or recognize them such that it honors those now affected?

- Do the symbols honor heroic acts by some (often whites and men) but not others?

- Has a positive symbol fallen into disrepair, so that it reflects disrespect rather than respect?

- Will the symbol stimulate hateful feelings among a portion of the community, such that it might incite violence targeted against people in a different group?

- Does the symbol convey false information about the nation’s or community’s ideals?

Relocation or destruction of a symbol that offends or venerates hate is the most obvious way to change the environment. It may sometimes be the best solution. In fact, the failure to move a symbol expeditiously may result in violence. A number of U.S. cities and campuses, for example, removed Confederate statues proactively after watching the violence that occurred in in the 2017 Charlottesville “Unite the Right” protest focused on the potential relocation of a statue of Confederate military commander Robert E. Lee.

Nothing is set in stone, even those things that appear to be. [H]istory, whatever else it can contribute, confers no absolute entitlements in relation to the streets and squares of the modern city.

– Dominic Bryan et al., regarding Belfast, Northern Ireland[1]

At other times, though, a group may give a symbol such cultural significance that relocation may spark conflict while achieving little. Planners may want to consider other options illustrated below, such as:

- relocating from a busy public space,

- finding a new name to replace offending ones,

- creating new spaces,

- setting up temporary exhibits,

- adding enactments and explanations,

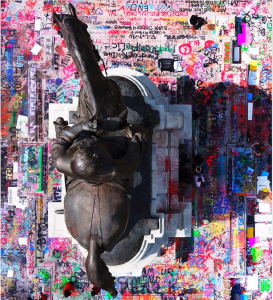

- deliberately allowing the space to become overgrown and covered with graffiti through neglect to communicate its lack of connection to the current community and its aims,

- augmenting something else that will gain more attention,

- creating positive events, holiday, and rituals,

- finding other ways to honor the identity that feels threatened (e.g., “that is our flag”) by the contemplated change, and

- eliminating all of something, such as all statues in public spaces or all buildings named for donors.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Symbols as part of other changes

A century ago, the Florida legislature permitted the City of Sanford to annex Goldsboro, a nearby city that had been founded and run by Black persons since shortly after the Civil War. Sanford renamed Goldsboro’s streets for white persons. After the Trayvon Martin killing in 2012 that led to years of demonstrations, the city began working to advance racial equity. As part of that effort, they worked with current residents of the Goldsboro area to re-name the streets for its Black founders and heroes.

Moving and contextualizing symbols

Budapest, Hungary, relocated statues of Soviet figures to a field outside town to acknowledge the hurt caused by constant interaction with the symbols while preserving the historical or cultural significance for those desiring to visit the statues. The architect designing the new space said, “This park is about dictatorship. And at the same time, because it can be talked about, described, built, this park is about democracy. After all, only democracy is able to give the opportunity to let us think freely about dictatorship.”[2]

Making the symbol interactive

The University of Virginia developed a new space, discussed in Goals, that reflects on the contributions of and suffering by enslaved persons. At the same time, the university created a community engagement committee to engage others with the space. This group, which included multiple descendants of enslaved persons at the University of Virginia, prompted them to form a new group, the Descendants of Enslaved Communities at UVA. That group now leads regular programming at the memorial and beyond, including guided tours, virtual forums, and community gatherings such as Descendants Day, an annual reunion held at the memorial. In 2025, the group also co-hosted a symposium on community-engaged reparative justice and continues to convene monthly “Meet Me at the Bench” sessions to foster dialogue and connection among descendants and community members.

Sensitivity to where people will take note of a symbol

To bring to mind the tragedy of police violence, organizers erected signs to commemorate George Floyd’s murder by a police officer with signs that the public would encounter at Floyd’s place of work and other spaces that he visited on a regular basis.

Temporary exhibits

A descendent of the mass killing in Bosnia created a temporary exhibit of coffee cups from the victims’ families, gaining permission to set them up for a few days in central places in a series of cities around the world and interact with visitors.[3] Sometimes people spontaneously create exhibits, such as the grieving persons who left stuffed animals and flowers on the sidewalk after Trayvon Martin was killed in 2012 by a neighborhood watch volunteer. The City of Sanford, Florida handled these temporary exhibits sensitively, discussing with residents how they might be preserved and moved to a location where they would be valued and away from destructive weather effects.

A new narrative for a historic space

For years, visitors to the Whitney Plantation, founded on the Mississippi River in Louisiana in 1752, perceived an idyllic setting, with no note of the plight of enslaved plantation workers. A few years ago, organizers changed the tours to focus on the suffering endured by enslaved persons, including enactments, thereby creating a symbol that teaches the horrors of slavery.[4]

A new museum

The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati offers exhibits, learning materials, stories, and events that attract visitors from across the nation to a portion of the Ohio River that was a crossing point to freedom for thousands of enslaved persons. The goal is to promote freedom today.

No new statues

British columnist Gary Younge argues that all would be better off to take down the old statues and refrain from erecting new ones. The new ones, he argues, will likely be the subject of controversy in 50 years or so. He suggests instead that we honor those we admire through the educational curricula, museums, and celebrations.[5]

A new celebration

The nation in 2021 recognized Juneteenth –June 19 – as a federal holiday. A number of cities and states had already given it official recognition. Juneteenth was celebrated previously primarily by Black Americans as the day that slaves in Texas first received the benefit of President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, issued about two and half years before they learned about it.

Making the celebration more universal is aimed at encouraging all to honor that history and promoting understanding. Celebrations sometimes include singing, street fairs, historical reenactments, and prayer breakfasts.

Framing options around community vision, not binaries

Rather than framing the discussion around a binary choice—such as whether to keep or remove specific monuments—Jacksonville leaders designed their dialogue forums to explore what kind of city residents wanted to build together. Participants considered a range of approaches to conveying history in public spaces, and discussion guides emphasized values, context, and shared aspirations, helping the community think beyond symbolic decisions toward long-term goals.

- Dominic Bryan et al., Civic Identity and Public Space: Belfast Since 1780, at 229 (2019). ↵

- Budapest Connection, https://budapestconnection.com/memento-park/. ↵

- Kerry Whigham, The Power of the Past – The Role of Historical Narratives in the Perpetration and Prevention of Mass Atrocities, May 21, 2021. ↵

- David Amsden, Building the First Slavery Museum in America, New York Times Mag. (Feb. 26, 2015), https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/01/magazine/building-the-first-slave-museum-in-america.html. ↵

- Gary Younge, Why Every Single Statue Should Come Down, The Guardian (June 1, 2021), https://www.theguardian.com/ artanddesign/2021/jun/01/gary-younge-why-every-single-statue-should-come-down-rhodes-colston. ↵