1 Theories of Innovation Adoption and Real-World Case Analyses

By Marcia Ham

Introduction

There are many innovations being developed every day around the world. Some make it to the national and international stage becoming a ubiquitous part of everyday life. Some innovations become important for select groups of people and unknown to individuals outside of those user groups. Many more innovations never make it too far outside their close circle of developers. What causes one innovation to change the manner in which society functions and another to be cast off into nonexistence has been the subject of research and analysis with experts drawing different models and developing overlapping theories as to the cause of successful diffusion of innovations. This chapter will highlight the main tenets of four diffusion theories and models – Innovation Diffusion Theory, Conerns-based Adoption Model, Technology Acceptance Model, and The Chocolate Model – and analyze two current, real-world cases in light of the frameworks presented by these theories. Each case relates to technology use at the higher education level at institutions in the United States, although the potential impact of these innovations is not necessarily confined to within the United States.

An Overview of Four Theories and Models

Rogers’ Innovation Diffusion Theory

Before diving into theories and models for innovation diffusion, it is worth taking a step back to understand what is meant by innovation, innovation adoption, and diffusion. In his editorial “What is Innovation?”, Damiano, Jr. (2011) refers to the Merriam-Webster dictionary definition which defines it as “the introduction of something new” where that something could be an idea, process, or product. Straub (2009) describes adoption as when an individual integrates a new innovation into their life and diffusion as “the collective adoption process over time.” Straub (2009) notes that adoption-diffusion theories, such as those that will be discussed in this chapter, “refer to the process involving the spread of a new idea over time (p.62).”

In 1962 Everett Rogers introduced his Innovation Diffusion Theory (IDT) which has been referenced often in case analysis since. It provides a foundation for understanding innovation adoption and the factors that influence an individual’s choices about an innovation. Rogers’ theory is broad in scope which lends itself to being flexible across many contexts but also difficult to use as a process model when planning for organizational change due to adoption of an innovation (Straub, 2009). There are four main components in Rogers’ diffusion theory: the innovation, communication channels used to broadcast information about the innovation, the social system existing around the adopters/non-adopters of the innovation, and the time it takes for individuals to move through the adoption process. The interaction of these components helps one understand why an individual chooses to adopt and innovation or not (Straub, 2009). A sub-process of diffusion in Rogers’ theory is the innovation decision or process which leads to adoption or rejection of the innovation. Rogers presents five stages potential adopters move through in this process. The first is seeking knowledge about the innovation and its function. The second is persuasion when the potential adopter formulates an opinion about the innovation. The third stage is when a decision is made to adopt or reject the innovation. The fourth stage occurs when the adopter implements the innovation. Finally, the adopter reaches the confirmation stage where they seek reinforcement of their decision to adopt the innovation. Here they may continue implementing the innovation as they experience its benefits or they may change their decision and reject the innovation (Rogers, 2003).

Rogers extends beyond the adoption process by identifying five attributes that affect whether an innovation is adopted or not: relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability. Relative advantage refers to how much greater or lesser the benefits of the innovation are compared with the alternatives. How well the innovation fits with a potential adopter’s existing process or workflow is its compatibility. The more difficult to learn and implement an innovation is perceived to be, the less likely it is to be adopted. This is because its complexity is perceived to be too high. Potential adopters are more likely to accept innovations they have an opportunity to experiment with and test out before making a decision whether to adopt or not; this refers to their trialability. Observability occurs once an innovation has been adopted and diffused across enough people within a culture system that those who previously had not thought about adopting it, change their minds or at least begin considering adopting the innovation (Rogers, 2003). Many personal technologies such as the smart phone and FitBit type devices have experienced widespread diffusion due in part to their high observability. Some universities have waited until there was high visibility of others implementing online courses before they began doing the same. This allowed them to see the success or failure of the strategy along with learning from the challenges of the early adopters. This example also demonstrates the impact of time on diffusion which Rogers (1962/2003) discusses in more depth in his book Diffusion of Innovations.

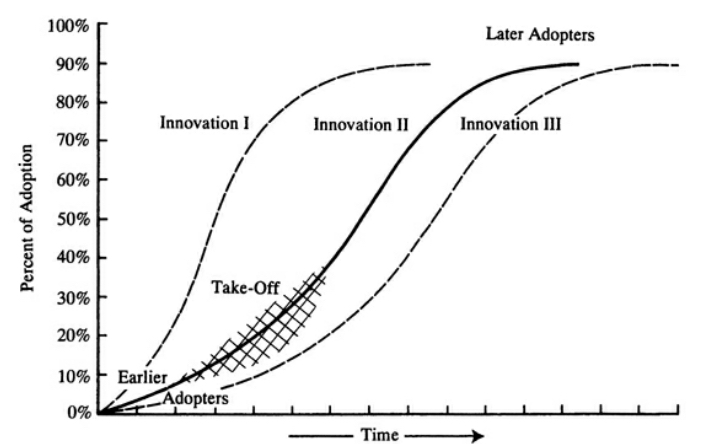

Examples of organizations applying IDT to help analyze current practices and plan for more effective diffusion of innovations may be useful to understanding the impact that Rogers’ theory can have in different contexts. “Understanding Academic E-books Through the Diffusion of Innovations Theory as a Basis for Developing Effective Marketing and Educational Strategies” was a study of e-book usage among university students and faculty was conducted and the results plotted along Rogers’ Innovation Curve shown in figure 1. Findings indicated which library patron groups were adopting e-books and at what level. These findings can be used to plan tailored marketing strategies for each group to drive further adoption of e-books which cuts costs to students and to libraries (Raynard, 2017). “Integrating Mobile Devices into Nursing Curricula: Opportunities for Implementation Using Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Model” was a study relating to the integration of mobile devices into nursing curriculum was analyzed through IDT. The goal of the analysis was first to categorize strategies for the adoption of mobile technologies in nursing education then, once a decision to adopt is made, apply the phases of the theory to aid in stakeholder acceptance (Doyle, Garrett, & Currie, 2014). Another study, “An Innovation Diffusion Approach to Examining the Adoption of Social Media by Small Businesses: An Australian Case Study,” was conducted in Australia around small business adoption of social media. Researchers used Rogers’ theory to help understand the experiences of small businesses using various social media platforms and where they stood on the adoption continuum and what factors impacted their decisions to either adopt or reject the use of social media in their business practices (Burgess, Sellitto, Cos, Buultjens, & Bingley, 2017).

Figure 1 – The diffusion process by innovation with the percent of adoption over time (Rogers, 2003, p. 11).

Hall’s Concerns-Based Adoption Model

Stemming from the need for a model particular to educational environments due to their traditional top-down approach to change, Hall (1979) developed the Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM). CBAM approaches innovation adoption from the perspective of those impacted by the adoption of the innovation and also charged with implementing the subsequent change – namely teachers in an educational context. The idea is that by addressing the concerns of the teachers during the adoption process, the challenges experienced during the change process will be lessened. There are six assumptions in CBAM:

- Change is a process, not an event.

- Change is accomplished by individuals.

- Change is a highly personal experience.

- Change involves developmental growth.

- Change is best understood in operational terms.

- The focus of facilitation should be on individuals, innovations, and context. (Straub, 2009)

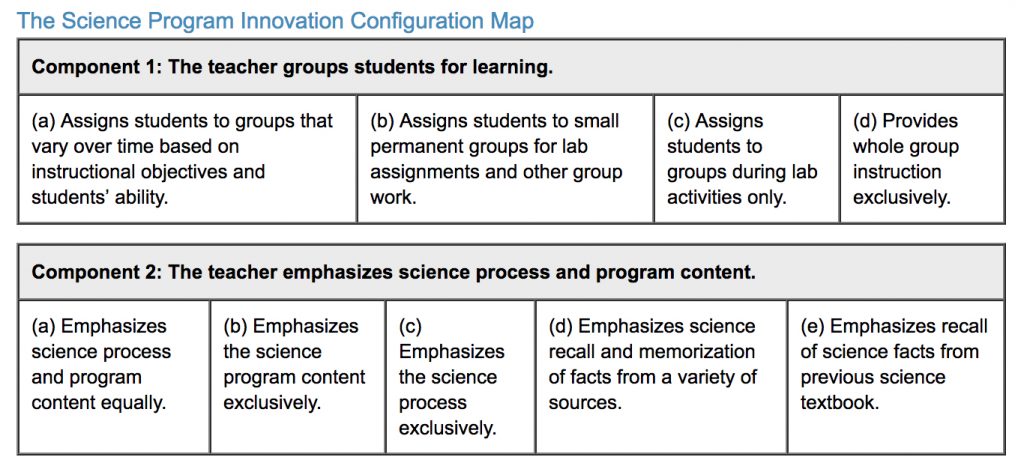

Three components of the CBAM, formed from the six assumptions, that inform a leader planning for change are the stages of concern (SoC), levels of use (LoU), and innovation configuration (IC). The SoC refers to individual characteristics relative to teachers concerns for themselves and for their students during the adoption process and is the main premise on which the CBAM was created (Straub, 2009). The SoC scale breaks down teachers’ concerns into seven stages during the adoption process. Stage 0 – awareness concerns – indicates that the innovation is of no concern to users, or adopters, because they do not know it exists. Stage 1 – information concerns – is when potential adopter are concerned about gathering more knowledge about the innovation. Stage 2 – personal concerns – is when the users perceive the innovation to pose a personal threat. They may have doubts or lack self-confidence about their ability to use the innovation. Stage 3 – management concerns – typically manifest after the first 24 hours of using an innovation when potential adopters struggle with the logistics, coordination, and the time it takes out of their schedules to learn and use the innovation. Stage 4 – consequences concerns – happens when potential adopters reflect on the potential affect the innovation will have on others such as students in many educational contexts. Stage 5 – collaboration concerns – usually is shared by the change agents which are typically administrators or team leaders. In this stage, there is a concern around bringing user groups together in forming best practices in using the innovation effectively. Stage 6 – refocusing concerns – is when users consider whether the proposed innovation is actually the best approach to use in achieving their goals or perhaps another innovation would be more suitable and had a greater impact (Hall, 1979). The LoU and IC refer to innovation characteristics. The LoU scale breaks down the stages of behavior as teachers pass from a lower level of use to higher levels of use (Straub, 2009). The innovation configuration (IC) refers to the process for implementing the innovation and is sometimes more successfully carried out when presented in a map as shown in the example in figure 2 (American Institute for Research, 2010).

Figure 2 – An example of an IC map for a new science program. Individual components needing to be addressed are separated out then broken down into the (a) ideal state of adoption to the (d) or (e) least ideal state of adoption (image from “Innovation Configuration: Concerns-based Adoption Model,” copyright 2010 by the American Institute for Research).

Although the teachers are seen as adoptees instead of adopters in the CBAM model, they also have the role of change agent in order for successful adoption to occur in the classroom. One might then see the students as receivers of the change, yet the CBAM model only focuses on the concerns of the teachers because of their role as change agents. Another note about this model is its apparent focus on negative opinions from teachers regarding innovation. As was mentioned in the overview of Rogers’ theory, opinions formed about an innovation – whether positive or negative – can each have an impact on the adoption of the innovation (Straub, 2009).

Technology Acceptance Model

Continuing along the theme of opinions and attitudes impacting innovation adoption, Davis’ (1985) Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) asserts that it is in fact a potential adopter’s attitude and expectations of the innovation that affects the chances for its adoption (Davis, 1985). Two focus concepts in TAM are how the innovation is perceived by the potential adopter related to its ease of use – how easy the innovation will be to learn and implement – and its potential usefulness – the degree to which the innovation will improve the user’s personal or job-related performance (Straub, 2009). Of the two elements, Davis believed that ease of use has a direct impact on perceived usefulness as, the easier an adopter perceives an innovation to be able to use, the greater chance they will use it and experience higher productivity thus proving to be useful to the adopter (Davis, 1985). In a later study, Davis concluded that there was a higher correlation between perceived usefulness and technology adoption than between perceived usefulness and adoption. From his test results, he surmised that it would not matter how easy a technology is to learn; people would not adopt it if they did not perceive it to be useful in increasing their productivity (Davis, 1989).

An example of the application of TAM to analyze adoption of an innovation comes from a study in the UK examining the key factors affecting whether someone participates in an online travel community. The study looked at compatibility, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness among other factors detailed in TAM but not discussed in this chapter. The researchers concluded that all factors played an important role in determining participation in online travel communities (Agag & El-Masry, 2016).

The Chocolate Model

These impactful factors can also be seen in Diane Dormant’s more recent model – The Chocolate Model – for innovation adoption and change (Dormant, 2011). The Chocolate Model focuses on innovation adoption and change related to an organization. It is structured around four elements: change, adopters, the change agent(s), and the organization – CACAO when made into an acronym for ease of recollection and use for planning. Unlike Rogers’ Innovation Diffusion Theory, the Chocolate Model can be applied when planning for organizational change and innovation adoption. The process flows as follows: first, analyze the change whether it is a new system or innovation (Dormant, 2011). This is similar to the first step of seeking knowledge that is in Rogers’ (2003) adoption process. The second step is to analyze the adopters of the change. Third, identify the change agents. At this point, a plan is developed. The next step is to examine the organization where the change process is expected to occur as well as analyzing the larger context of the organizational change – how it impacts other aspects of the whole organization. Before implementing, the plan may be revised based on the outcomes of the organizational analysis (Dormant, 2011).

The Chocolate Model aligns well with TAM in that change characteristics are similar. As in TAM, adopters look at the relative advantage of the innovation or change (Dormant, 2011) – referred to as the “perceived usefulness” in TAM (Straub, 2009). Adopters also look at the simplicity and compatibility the innovation represents – the “perceived ease of use” in TAM (Dormant, 2011; Straub, 2009). Two elements not discussed in TAM but called out in the Chocolate Model are the adaptability of the innovation to the specific needs of the adopters and the social impact of the change – what the change will mean for the social structure and climate of the organization (Dormant, 2011).

Adoption and Diffusion Case Analyses

This section of this chapter analyzes recent innovations and their adoption and diffusion in two higher educational settings using elements from the aforementioned theories and models. The first case focuses on the Starbucks College Achievement Plan which was developed as a partnership with Arizona State University (ASU). The second case looks at Oklahoma State University’s Mixed Reality Lab.

Case 1: Starbucks College Achievement Plan

It has been said that sometimes the adopter of a change is not the actual beneficiary of the change (Wisdom, Chor, Hoagwood, & Horwitz, 2013). Such is the case of the Starbucks College Achievement Plan, introduced in 2014, that helps employees of Starbucks gain access to college and earn their degree. The program was developed in answer to the high number of undergraduate students having to work while going to school in order to pay for rising tuition costs. An increasing number of these students end up dropping out of school as the time demands become too unmanageable. The Starbucks College Achievement Plan allows eligible Starbucks employees to receive full tuition coverage from the company so they can work on one of over 70 online degree programs offered through ASU and taught online by ASU faculty. Beyond the financial aid offered, each employee-student receives support from an enrollment counselor, a financial aid advisor, an academic advisor, as well as a success coach (“Starbucks College Achievement Plan: Education meets opportunity,” n.d.). In March 2017, Starbucks announced Pathway to Admission which allows those Starbucks employees who fall short of the academic requirements for enrollment in ASU to take a series of online courses through the university’s Global Freshman Academy in order to become academically qualified for enrollment in a degree program (Faller, 2017).

The goal of Starbucks is to have 25,000 of their employees graduate through the College Achievement Plan by 2025. The first graduating class in 2015 through the program totaled 3 students (Rochman & Peiper, 2017). That number rose to 100 a year later (“The class of 2016,” 2016) and the graduate numbers from the program in June 2017 was 330 (Rochman & Peiper, 2017). At that time, Philip Reiger, the university dean for educational initiatives and CEO of EdPlus at ASU, estimated the number of graduates through the program by the end of 2017 to reach 1,000 (Young, 2017). Reiger’s estimate proved to be on target as the December 2017 graduating class from the program exceeded 1,000 students. At the same time, more than 9,000 Starbucks employees were students in the program (Rochman & Peiper, 2017) indicating a growth in future graduation numbers.

Although Reiger did not think that ASU would continue to actively search out additional such partnerships with other large companies, in August 2017, ASU partnered with adidas as they prepared to pilot a similar program to the College Achievement Plan in January 2018. In the pilot, 100 full-time adidas employees received a large portion of their tuition in an ASU Online degree program covered by the company. “The program reflects both adidas’ and ASU’s commitment to social embeddedness detailed in the Global Sport Alliance. Its objective is to bring together education, athletics, research and innovation to explore topics including diversity, sustainability and human potential – all through the lens of sport” (Greguska, 2017). The goal of the partnership is to expand to international employees over the next three years (Greguska, 2017).

The case of Starbucks College Achievement Plan in partnership with ASU can be analyzed through Rogers’ Innovation Adoption Theory with a few modifications. Looking at the four elements of diffusion – the innovation, communication channels, social system, and time – it is evident that the innovation in this case is the idea to leverage the online degree programs already offered by ASU to provide an avenue of educational access and achievement for Starbucks employees. Communication of the program happened through internal company channels, ASU News and the university website, other news media outlets such as The Atlantic magazine and higher education online journals, conference presentations, interviews, and, presumably, word of mouth among employees (“The Class of 2016”, 2016). The social system and culture at Starbucks that encouraged this idea to come to fruition started at the founding of the company with Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz when he dreamed of a company based on the desire not just for earning profits but for giving back to the community and hiring veterans, refugees and at-risk youth (Faller, 2017). It is apparent in the partnership that Starbucks is not turning a profit from the College Achievement Plan but, in the words of Schultz, “We as a company want to do something that has not been done before. That is, we want to create access to the American dream, hope and opportunity for everyone” (“Starbucks College”, n.d.). The time given for implementation spans from 2017 to 2025 and possibly beyond.

Analyzing the attributes influencing the adoption of the Starbucks College Achievement Plan is where a focus on the adopter and beneficiary get a little muddled. If the company and university leaders drawing up the plan for implementation are considered the change agents – as they might be if analyzed through the Chocolate Model (Dormant, 2011) – then the employees carrying out the implementation such as HR officers at Starbucks handling employee benefits, ASU admissions and enrollment officers, financial aid advisors, academic advisors, success coaches, and others might be considered the adopters of the innovation. The beneficiaries are the Starbucks employee-students.

Although internal corporate politics are unknown, there appears to have been little resistance to adopting the plan for partnership between Starbucks and ASU to provide this benefit to employees of the company. Referencing the TAM and the Chocolate Model, the innovation was perceived to be easy to implement since the complex system for delivering the education was already in place at ASU thus satisfying the need for simplicity and compatibility outlined in the Chocolate Model. There was also a perceived usefulness – or relative advantage – of the change as it aligned with the foundational corporate mission at Starbucks to give back to the community. In this case, giving back meant opening access to the “American dream” to anyone willing to chase it. From Arizona State university’s (ASU) perspective, the program would bring in thousands of new students and tuition revenue to the university without additional effort on their part.

When looking at the change process Starbucks went through to make their program a reality through the lens of the Chocolate Model, they followed the steps outlined in the model. From analyzing the change desired, who the adopters and change agents were, developing their action plan, analyzing the change from a holistic perspective across their organization, they then saw a need to revise the plan even as it was being implemented. What they identified was that as wonderful as the College Achievement Plan was, it was not useful for many Starbucks employees because they couldn’t gain admittance into ASU due to lack of academic qualifications. In order to increase the usefulness and success of the program, Starbucks expanded the program in spring of 2017 by adding Pathway to Admission which would allow Starbucks employees to gain the necessary academic credentials for ASU admission by taking missing credits through ASU’s Global Freshman Academy (Faller, 2017). Reflecting back on the graduation rates from the program, it is interesting to note that by December 2017 there were over 9,000 students enrolled in the program and to wonder if opening up access to the program through Pathway to Admission may have spurred on that growth.

Case 2: Oklahoma State University’s Mixed Reality Lab

Oklahoma State University established the Mixed Reality Lab in 2015 within the College of Human Sciences. The lab is affiliated specifically with Department of Design Housing and Merchandising (Department of Design, Housing, and Merchandising, n.d.). The lab is host to mainly design classes although according to Chandrasekera, an associate professor in the department, they are working to inform other departments about the lab and hope to bring in classes from areas outside of design to innovate in the lab (Grush, 2016). The lab is outfitted with state of the art virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) equipment for students, faculty and researchers to use in their academic and research pursuits. Funding comes from the College of Human Sciences although Oklahoma State partnered with Crytek – a video game development company specializing in 3D games – to be one of the nearly 50 universities around the world collaborating as part of the company’s educational virtual reality initiative – VR First – which supports the participating lab with the latest technology and supports research projects conducted in the lab space. VR First acts as a device and vendor agnostic incubator for innovative virtual reality ideas within lab spaces around the world, helping developers navigate the business and legal aspects of VR application development while creating the application itself. A current VR First project being conducted in Oklahoma State’s Mixed Reality Lab centers around the development of an augmented reality mobile app to assist people with physical disabilities and those with mild memory loss in the location of objects (Ergurel, 2017).

In the spring of 2018, the College of Human Sciences ran a hackathon which was held in the Mixed Reality Lab. Teams of five – made up of students, faculty, community members – worked to solve real-world problems. The hackathon was co-sponsored by Wal-mart and presentations were judged by both Oklahoma State and Wal-mart representatives based on preset criteria. Team participants came from many departments around the university from design and engineering to educational technology. Data was collected throughout the hackathon on how the VR and AR technology was being used to solve problems and how the teams worked together. The results of that research will be shared during conferences at the university in the fall of 2018 (Grush, 2018).

Examining the adoption of the Mixed Reality Lab at Oklahoma State through the four components of diffusion theory, innovation is arguably the most significant component. The relative advantage of the lab is its ability to provide one space for those interested in VR and AR technology to investigate it and work on projects using the most advanced technology, thanks in part to the partnership with VR First. Students with experience using this technology are viewed to have an advantage in the job market after graduating. Although integrated with design classes in the College of Human Sciences, compatibility with current university research and broader course delivery is not evident since the Mixed Reality Lab employed new technologies and was the first lab space of its kind on campus. Thus, the complexity of the lab is significant. However, those operating the lab are encouraging of all interested in trying out the technology to do so making the trialability of the lab space rate high. The observability of the work happening in the lab has improved with outreach efforts by faculty in charge of the lab to other departments to visit and use the lab. Observability improved during the promotion of the hackathon and will continue to increase as researchers using the space present their findings at conferences and in articles. There is also the matter of observability of the VR and AR technology itself which has increased in recent years as more individuals see others purchasing their own equipment for entertainment purposes. However, widespread use of the technology has not diffused across society or the Oklahoma State campus at a high rate yet.

Why the Mixed Reality Lab has not enjoyed regular use across university programs may be due to the social system of the university which is complex in itself. For faculty who are not familiar with the technology, who do not work with it or see a need to incorporate it in their teaching and research, the Mixed Reality Lab is irrelevant to them. On Roger’s innovation curve in figure 1, they would be the late adopters if and when the VR/AR technology diffuses across programs. At this point in time, those who are using the lab for research and classes would be considered early adopters. For all of the outreach the faculty running the lab have done across campus to bring in users from all colleges and departments, it may be that some faculty are more naturally inclined toward incorporating VR/AR technology in their research and course learning experiences while others are not. This circles back to the impact of perceived usefulness on technology adoption outlined in TAM (Davis, 1989). If faculty of certain departments do not see the benefits of changing their strategies for instruction or research to include VR/AR use, then the potential for them to adopt the technology is quite slim. No amount of support resources could be provided to overcome the perceived lack of usefulness the faculty may have for the technology. So it seems that use of the Mixed Reality Lab has not yet reached the rapidly rising part of the innovation curve showing the time to adoption highlighted in IDT (Rogers, 2003).

For usage of the Mixed Reality Lab to take off, the lab faculty and staff will need to target their communications about the ways different departments might use the technology specifically to those departments. General information about the lab will not suffice. VR or AR may not be appropriate integrations for all courses depending on the department and subject area taught. However, if just one, or a few, faculty members from each department open to investigating the technology become engaged in integrating VR or AR in their teaching and/or research practices and have opportunities to share their achievements and experiences with others in their department, then perhaps use of the lab will begin to grow. Those early adopters in each department would become more effective agents of change than the lab faculty because they are from the individual departments and would be seen as having more credibility by their colleagues when communicating about the benefits of adopting the technology. This illustrates the importance of considering the culture of the organization in which the potential adopters operate on a daily basis. In this case, the action steps toward driving the adoption of the Mixed Reality Lab need to somewhat align with the culture and customs of departments before any movement toward adoption can be achieved.

Conclusion

Adoption of innovation can be a challenge let alone diffusing the innovation across an organization, group, or society. There are many theories and models for innovation adoption and diffusion which contradict each other in some aspects and overlap in others. Some models are best suited for specific situations, such as CBAM for education, and others such as Rogers’ Innovation Diffusion Theory are so broad that their flexibility is also their weakness when trying to apply them in particular contexts (Straub, 2009). The commonalities that are found among most theories and models relate to the influence of the following on whether an innovation is adopted or rejected:

- Socio-political and external factors (e.g. environment, policies and regulations, social networks)

- Organizational characteristics (e.g. leadership, social climate, organizational structure)

- Innovation characteristics (e.g. complexity, compatibility, trialability)

- Staff/Individual characteristics (e.g. attitudes, knowledge, motivation)

- Client characteristics (e.g. readiness, capacity to adopt) (Straub, 2009)

Each of these characteristics appear in most models though under different descriptors as is the case with TAM and an adopter’s “perception of usefulness” which is essentially the same as “relative advantage” in the Chocolate Model (Davis, 1985; Dormant, 2011).

Analyzing organizational change as it relates to innovation adoption can be useful for one’s own organization when considering adopting an innovation. First, by analyzing another organization’s change process using an appropriate model or theory, the results can help leaders avoid mistakes made by the analyzed organization. Given that each organization has their own particular social and operational culture, leaders may find it beneficial to apply a model to analyze previous change initiatives to uncover what worked well, what did not, and why. There is not one “right” model for every change situation and every organization. It may be that Rogers’ Innovation Diffusion theory is too broad in scope to help change agents effectively carry out change in their particular organization. In that case, looking at the context of the desired change may help in the selection of a model such as CBAM when planning for adoption of an innovation in an educational setting. Based on CBAM, creating an innovation congifuration map for the change desired can help define the specific behavioral goals that would indicate successful innovation adoption. If the innovation to be adopted is highly technical in nature, change agents may look to TAM for guidance in planning for adoption focusing efforts on the ease of use and perceived usefulness of the technology to be adopted. If planning for organizational change, such as workflow processes, then the Chocolate Model may be useful as it focuses on the structures in place at an organization and the roles people play in making the change successful or not successful. If, however, the goal is to gather initital information on what should be considered before implementing any sort of organizational change around an innovation adoption, then applying Rogers’ Innovation Diffusion theory in studying how change occurred in a similar organization may offer insight into strategies for creating adopter acceptance of the new process or technology, the methods for communication about the change, and how to handle early, middle, and late adopters in accordance with organizational culture.

There are opportunities for gaining insight about innovation adoption outside of the theories and models discussed in this chapter when studying specific cases such as Starbucks’ College Achievement Plan and Oklahoma State’s Mixed Reality Lab. For example, Starbucks’ made a shift in the middle of their program roll-out as they noticed many employees unable to participate in the program due to lack of academic qualifications. The company worked with ASU to come up with a supporting program to help those employees gain the qualifications needed to take advantage of the College Achievement Plan. If Starbucks had not been diligent in tracking enrollments and discovering why some employees were not involved in the program and then been flexible enough to add on to the initial plan with the Pathway to Admission program, the goal of the College Achievement Plan to graduate 25,000 student employees by 2025 would have been in jeopardy. Thus, applying models for analyzing an organization ready for change is only one part of the research that should be done before implementing a plan for change. Studying other organizations through specific models while being open to lessons learned outside of the model structure provides important insight for developing a plan appropriate to an organization’s needs.

References

Agag, G., & El-Masry, A. A. (2016). Understanding consumer intention to participate in online travel community and effects on consumer intention to purchase travel online and WOM: An integration of innovation diffusion theory and TAM with trust. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 97-111.

American Institute for Research. (2010). Innovation configurations: Concerns-based adoption model. Retrieved from https://www.air.org/resource/innovation-configurations

Burgess, S., Sellitto, C., Cox, C., Buultjens, J., and Bingley, S. (2017). An innovation diffusion approach to examining the adoption of social media by small businesses: An Australian case study. Pacific Asia Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 9(3), 1-24.

Damiano Jr., R.J. (2011). What is innovation? Innovations: Technology and Techniques in Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery, 6(2), 65.

Davis, F. D. (1985). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results. (Doctoral dissertation), Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved from DSpace@MIT Database. (Accession No. 14927137)

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340.

Department of Design, Housing, and Merchandising. (n.d.) Mixed Reality Lab. Retrieved from http://trcf52.okstate.edu/x/index.html

Dormant, D. (2011). The Chocolate Model of Change. San Bernadino, CA.

Doyle, G. J., Garrett, B., & Currie, L. M. (2014). Integrating mobile devices into nursing curricula: Opportunities for implementation using Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation mode. Nurse Education Today, 34(5), 775-782.

Ergurel, D. (2017). VR First is building virtual reality labs in 50 universities around the world. Haptic.al. Retrieved from https://haptic.al/vr-first-is-becoming-an-independent-vr-incubator-to-build-50-labs-in-universities-84a33ab99ecb

Faller, M. B. (2017). Starbucks, ASU Online partnership expands with Pathway to Admission. ASU Now. Retrieved from https://asunow.asu.edu/20170322-asu-news-starbucks-partnership-expands-pathway-to-admission

Greguska, E. (2017). Pilot program to cover majority of ASU Online degree costs for 100 adidas employees, with shared goal of helping people succeed. ASU Now. Retrieved from https://asunow.asu.edu/20170824-asu-news-adidas-digital-education-partnership-scholarships-employees

Grush, M. (2016). Mixed reality: From the design lab to the professions. Campus Technology. Retrieved from https://campustechnology.com/Articles/2016/11/15/Mixed-Reality-From-the-Design-Lab-to-the-Professions.aspx?Page=1

Grush, M. (2018). Hacking real-world problems with virtual and augmented reality. Campus Technology. Retrieved from https://campustechnology.com/articles/2018/02/12/hacking-real-world-problems-with-virtual-and-augmented-reality.aspx

Hall, G. E. (1979). The concerns-based approach to facilitating change. Educational Horizons, 57(4), 202-208.

Raynard, M. (2017). Understanding academic e-books through the diffusion of innovations theory as a basis for developing effective marketing and educational strategies. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(1), 82-86.

Rochman, B., & Peiper, H. (2017). Starbucks College Achievement Plan welcomes its 1,000th graduate. Retrieved from https://news.starbucks.com/news/starbucks-college-achievement-plan-welcomes-its-1000th-graduate

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations, 5th ed. New York: Free Press.

Starbucks College Acheivement Plan: Education meets opportunity. (n.d.). EdPlus at Arizona State University. Retrieved from https://edplus.asu.edu/what-we-do/starbucks-college-achievement-plan

Straub, E. T. (2009). Understanding technology adoption: Theory and future directions for informal learning. Review of Educational Research, 79(2), 625-649.

The class of 2016. (2016). The Starbucks College Achievement Plan. Retrieved from https://news.starbucks.com/collegeplan/2016graduationvideos

Wisdom, J. P., Chor, K. B., Hoagwood, K. E., & Horwitz, S. M. (2013). Innovation adoption: A review of theories and constructs. Administration Policy in Mental Health, 41(4), 480–502.

Young, J. (2017). ASU’s Starbucks deal was just the beginning. EdSurge. Retrieved from https://www.edsurge.com/news/2017-06-21-asu-s-starbucks-deal-was-just-the-beginning

Correspondence concerning this chapter should be addressed to Marcia Ham at ham.73@osu.edu