3 “ID 2 LXD” From Instructional Design to Learning Experience Design: The Rise of Design Thinking

By Ceren Korkmaz

Introduction

Stanford’s d.school is no ordinary design school. They boast that they do not teach “how to design” but rather “design thinking”, which is a concept taking over creative disciplines nowadays. That being said, design is basically a process of creative problem solving, and it can be applied to a vast variety of fields. With an immense amount of challenges to be tackled, education is no exception.

For years, instructional design was discussed by scholars and professionals alike in terms of how it could be utilized for optimizing learning. At heart, it is a concept of programming instruction to achieve better learning outcomes. The concept has branched out to be a profession rather than being a sole methodology for in-class practices. Nowadays, when a person puts “instructional designer” as a line in their resume, the common perception is that they are somehow involved in e-learning authoring. Meanwhile, the fast pace of technology has caused e-learners to have new demands from the format of the content they are learning, the number one being immersion. With the appearance of new learning technologies, instructional design is now shifting towards learning experience design, which has design thinking at heart. As design thinking values interdisciplinarity above everything else for problem solving, fresh opportunities for driving educational change emerge.

Now that the diffusion of design thinking is underway, it’s affecting the way learning designers approach their work. This chapter aims to focus on how instructional design (ID) is evolving into learning experience design (LXD), the underlying reasons, the place of Design Thinking during this process, and perspectives on the future of learning design.

“Instructional Design est. 1945”: The evolution of Instructional Design

Instructional design (ID) has many meanings attached to it. Nowadays, within educational settings, it is usually the careful planning, regulation, and assessment of learning activities that comes to mind. On the other hand, in professional environments, the immediate connotation is related to building training modules, most probably with technological aids. While instructional design might sound like a recent phenomenon due to technology utilization, its roots actually date back to the times of World War II (Dick, 1987).

The psychologists called out to action during this time were assigned the task of carrying out research to develop trainings for the military. They were also responsible for skills assessment and conducting “needs analyses” to select participants for a particular training. Among the people who were influential on the characteristics of the trainings developed were the psychologists Briggs, Gagné, and Flanagan (Reiser, 2001). Their influence comes from the fact that they based these training characteristics on instructional principles shaped by instructional theories, and research on human learning and behavior.

Once the war ended, in an attempt to solve the problems in instructional design, American Institutes for Research were founded. It was during second half of the ‘40s that the researchers started considering a training as a system, and developing planning, development, and assessment procedures (Dick, 1987).

What came afterwards was the Programmed Instruction Movement (Skinner, 1954). In this work that spans until mid ‘60s, they argued that the instruction should be given in small chunks, and the frequent questions that require explicit answers should be addressed to learners. Due to the immediate feedback they would receive, the learning would be maximized due to reinforcement. Upon the careful evaluation of the materials used, they would be revised and refined according to learner needs, which would enable learner self-pacing.

As much as Ralph Tyler is known as the originator of behavioral objectives, Benjamin Bloom and colleagues came up with their famous “Taxonomy of Educational Objectives” in 1956, having an impact on instructional design as we know it forever. Additionally, in an attempt to aid those who would like to design materials for programmed instruction, Mager (1962) wrote a book called “Preparing Objectives for Programmed Instruction” (Reiser, 2001).

In 1962, Glaser and Klaus introduced criterion-referenced measures in order to define entry-level and post-instructional student behaviors. This piece was published in a book edited by Robert Gagné who introduced another canonical concept to instructional design in Conditions of Learning (1965). He categorized five domains of learning outcomes as intellectual skills, cognitive strategy, verbal information, motor skills, and attitude. His theory argued that there needs to be certain prerequisites met under each of these domains for learning to occur.

The 1970s were marked by rising interest in creating various models for instructional design. During this period, instruction began to be perceived as more of a system, and many principles were suggested for systemizing it (Gustafson & Bratton, 1984). It was also around this time that graduate programs on instructional design began to be established (Reiser, 2001) and that Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations (PLATO) was created, and it could be dubbed as the first computer-assisted instructional endeavor. Along with the innovative advances such as PLATO and invention of personal computers, this era could be named as the emergence of distance learning as we know it.

By 1990s, the line of research shifted through cognitive psychology to constructivism, in which Dewey, Montessori, Piaget, Vygotsky, and Bruner are among the influential names. This theory prioritized authenticity, real-life problem solving, and self-pacing. Regarding instructional design, constructivism led the way of computers being utilized in more interactive ways rather than solely incorporating drilling. With the rise of the Internet use in the mid-90’s (Reiser, 2001), distance learning slowly started taking over, and it was instructional designers’ job to create online learning environments that did not solely transfer textbooks into digital platforms.

The 2000s brought along technological advances one after another, and in a very fast pace at that. Especially towards the end of the decade, the computers and devices went smaller and cordless; the Internet went wireless with bigger bandwidth; and social networking and media began to take over. Right now, as we are approaching the second decade of the millennium, the only way to describe the current state of instructional design is “Imagine the possibilities!” with the immense number of tools available. Although designers are indeed imagining, the highlight here is that instructional design is evolving into LXD which lies heavily on personalization / customization of learning and empathy.

“LX Designer Wanted:” The Emergence of Learning Experience Design

LXD is actually not a brand-new phenomenon, and it has been around for over ten years now. The term was coined by Niels Floor, a Dutch LXD pioneer in 2007 (Floor, 2018a). While there are many definitions of LXD out there, let’s look at the one that the originator created to offer a general understanding:

Learning experience design […] is the process of creating learning experiences that enable the learner to achieve the desired learning outcome in a human centered and goal-oriented way. (Floor, 2018b, para#1).

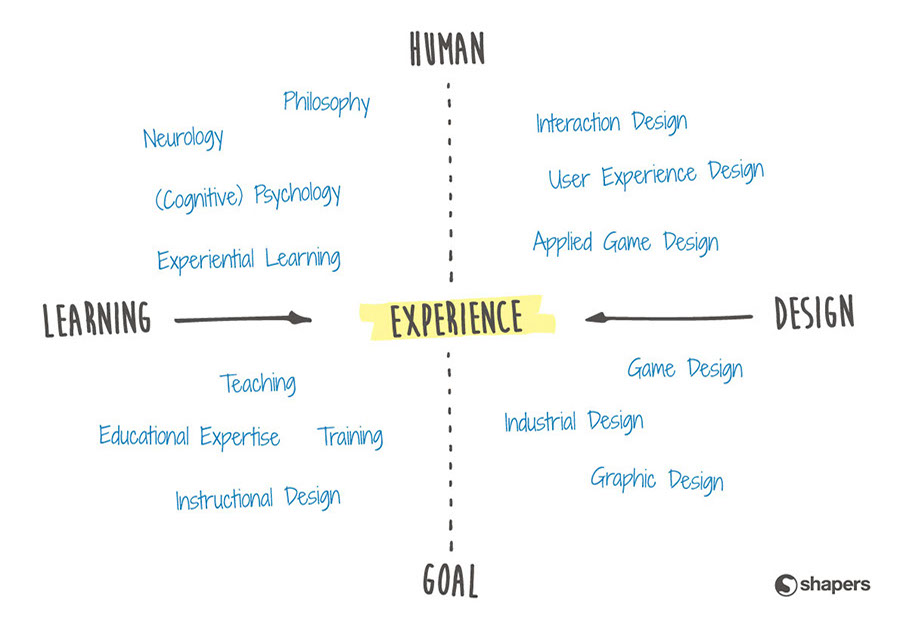

Then, what makes LXD different from instructional design? Just looking at the terms from an etymological perspective, instructional design emphasizes the source of knowledge — in other words, the planning of the teaching activities. However, LXD concentrates more on the destination of the knowledge, or the learner. As Matthews et al. (2017) also conclude, there is a heavy emphasis on empathy in LXD. It is plausible to claim that LXD pays attention to emotional design as Floor (2018) describes the fundamentals of LXD as (Figure 1):

- Human-centered

- Goal-oriented

- Theory of learning, i.e. familiarity with human cognition

- Learning put into practice

- Heavily interdisciplinary

Figure 1 – The Interdisciplinarity of Learning Experience Design Model (image from: http://www.learningexperiencedesign.com/learn-2.html).

A Universal LXD?

An internationally reputable architect, designer, and educator Ron Mace coined the term “universal design”. In 1997, he formed a committee of ten people and established The Principles of Universal Design (Connell et al., 1997). While these principles are aimed at creating a universal design mainly for architectural and industrial products, they are still valid for educational contexts, especially learning design, as well (Connell et al., 1997):

- Equitable use: The design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities.

- Flexibility in use: The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities.

- Simple and intuitive use: Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level.

- Perceptible information: The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities.

- Tolerance for error: The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions.

- Low physical effort: The design can be used efficiently and comfortably and with a minimum of fatigue.

- Size and space for appropriate use: Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use regardless of user’s body size, posture, or mobility.

Combining these with the foundations of LXD should give us an idea about the universal design of learning experiences. Although universality might give off the impression that universal design hinders personalization, it is still possible to customize the experience.

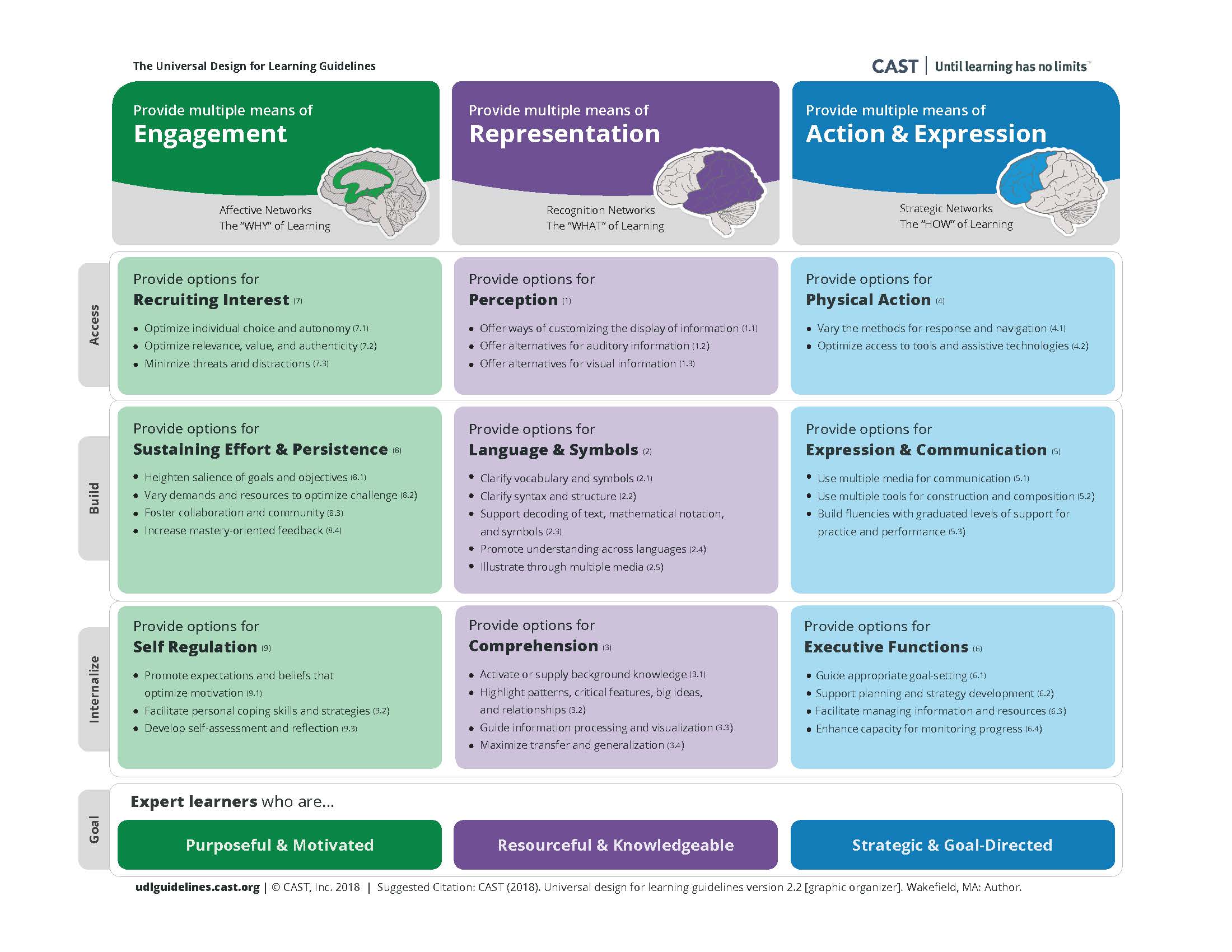

There have been multiple attempts at creating universal design principles for education as well (Palmer & Caputo, 2002; Deaton, 2016; CAST, 2018). In particular Chapter 2 of this eBook, recommends Universal Design for Learning as a way to sustain learning.

CAST established a set of guidelines for the “universal design for learning” framework whose principles were set forth by Anne Meyer and David Rose in the 1990s (Meyer, Rose, Gordon, 2014). The purpose of this work is to enable educators to optimize learning experiences with the help of learning technologies. Figure 2 shows a version of these guidelines as of July 2018.

Figure 2 – Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2 (CAST, 2018). Image source: http://udlguidelines.cast.org/binaries/content/assets/udlguidelines/udlg-v2-2/udlg_graphicorganizer_v2-2_numbers-yes.pdf

In her article, UX to LX: The Rise of Learner Experience Design, in which she focuses on the rise of LXD, Kilgore (2016) explains “User experience research methods and design thinking help us unpack the intangibles of the student experience” (Knott as cited in Kilgore, 2016, para#6). Then, what exactly is design thinking and why does it matter?

Design Thinking: An Approach for Diffusion of Innovation

A very explicit explanation of design thinking would be Wu’s (2017) title to her article in UX Collective, Is Design Thinking a Method of Design? In a similar vein, Johansson-Sköldberg, Woodilla and Çetinkaya (2013) found that there are multiple definitions for what design(erly) thinking means through doing a discourse analysis. Below are the multiple meanings found in the literature. One meaning that is particularly relevant to this chapter is “design and designerly thinking as a problem–solving activity” since design thinking is approached as a way of solving problems. Others meanings are (Kimbell, 2009):

- Design and designerly thinking as the creation of artifacts

- Design and designerly thinking as a reflexive practice

- Design and designerly thinking as a problem–solving activity

- Design and designerly thinking as a way of reasoning/making sense of things

- Design and designerly thinking as creation of meaning

As much as the definition of design thinking as a problem-solving activity goes back to early 1990s, the concept of design thinking has gone mainstream with the CEO of IDEO, Brown’s book (2009) Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation (also Brown & Katz, 2011). In their work, Brown and Katz mention that design thinking’s aim is to help people be as creative and innovative as possible in their problem-solving endeavors. So, rather than being a new way of designing for problem solving, it is a way to approach the problem itself. In order to get creative, the importance of interdisciplinarity is boldly emphasized much like LXD does.

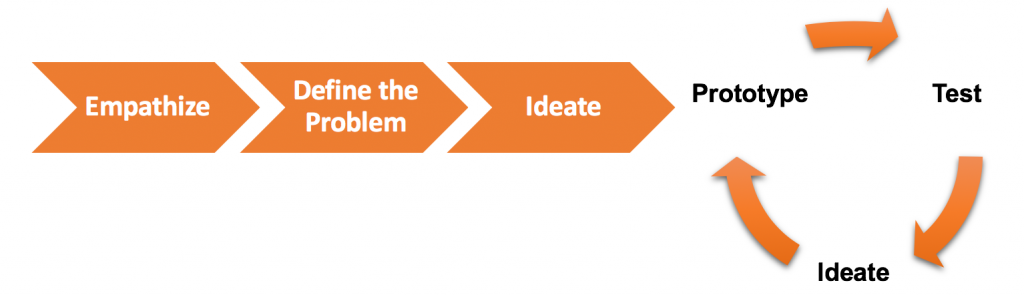

That is not to say that design thinking is only contained within the frame of practitioners. The framework has made its way into educational research, as well, with the project Design Thinking for Educators (Riverdale Country School & IDEO, 2012) observing: “Design thinking […] is a mindset. It’s about being aware of the world around you, believing that you play a role in shaping that world and taking action toward a more desirable future. It is human-centered, collaborative, experimental, and optimistic” (Riverdale Country School & IDEO, 2012). Figure 3 shows what the design thinking process looks like.

Figure 3 – Design Thinking Process (Brown, 2009).

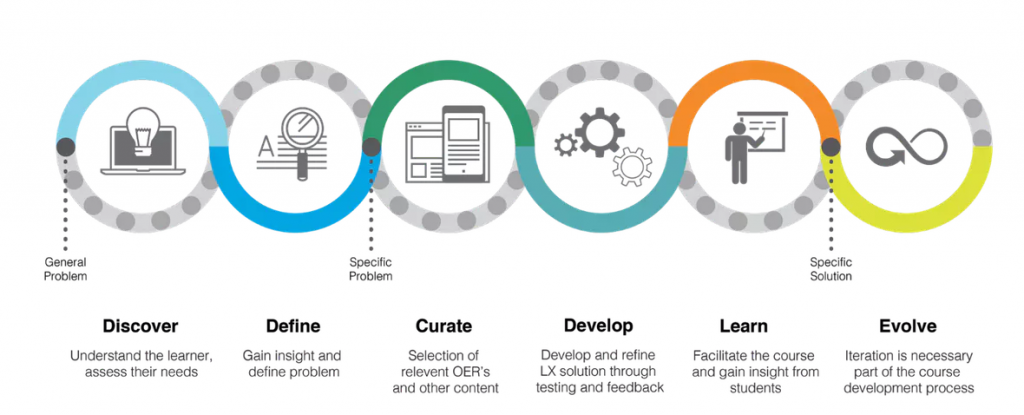

Utilizing this process, what a learner experience designer should do is, as repeated many times before, to empathize with the learners. Having open polls for potential learners or conducting interviews with them to learn about what kind of an experience they would want would surely help. In this phase, as the learners’ emotional needs are prioritized for optimal engagement, this step can be dubbed as the “emotional needs analysis”. The next step is naturally to define the problem. However, since we are talking about design thinking here, the approach should be out-of-the-box, approaching the problem with awareness and from many angles. After the problem is identified, the ideation, i.e. the brainstorming process, will begin preferably with the company of an interdisciplinary team. The next steps are prototyping, testing/piloting, and iterating this cycle until satisfactory results are achieved. Figure 4 depicts how design thinking can drive the LXD process.

Figure 4 – Design thinking in action in learning experience design (image from: https://www.edsurge.com/news/2016-06-20-ux-to-lx-the-rise-of-learner-experience-design). Image Credit: iDesign.

What’s Next for Designing Learning?

With the prevalence of virtual and augmented reality nowadays, the talk of LXD will not go anywhere soon. As instructional designers are slowly being replaced by LX designers, and schools like Stanford’s d.school claims that they are “not teaching design, but design thinking,” the question of “How can this be leveraged for the sake of educational change?” comes to mind. d.school offers tools for action exactly for this purpose.

Then, what are some things a learning experience designer can do to meet the rising expectations of “a good learning experience”?

Designing just for the learner

Empathy and emotional design lies at the core of LXD. As long as the learner gets the feeling of personalization from the experience, it is plausible to assume that it would be deemed as a “good” one (Milam, El-Nasr & Wakkary, 2008). This is the reason that stories that have multiple endings are really popular (Tyndale & Ramsoomair, 2016). In order to customize the experience for the learner, data analytics, i. e. their digital footsteps, are the number one source to go to.

Distance learning still rules supreme

The platform of choice to consider for the end-design should be mostly mobile due to the prevalence of handheld devices and the speed of learning, but laptops are still relevant (Pandey, 2018).

“The book or the movie?”

Books are becoming a nostalgic object as much as we would like to argue that leaving things to imagination is the better option. The busyness of day-to-day life creates impatience and leads to not investing long periods of time for trainings. Thus, videos are preferred over plain text, and everything shrinks down to “pill-size” portions that are, of course, as interactive as possible to engage the learner. For example, Chapter 4 discusses microcredentials as an innovation in teachers’ professional development. According to Trifecta Research (2015), 70% of Gen Z watches two hours of YouTube per day, which depicts the landscape of video consumption. At this point, it is up to the learning experience designers to rise to the challenge of not leaving out the vital details in the “book”, i.e. text that they are integrating into an online module.

Iterate, iterate, iterate

The more the module (product, training…) is revised based on the feedback gathered, the better it will be. Most important of all, it is vital not to restrain creativity throughout the design process. The teamwork of an interdisciplinary team is essential here so that the experience is a product of various fresh perspectives.

“Design” the experience

The Learning Design Starter Kit, Interaction Design Foundation, and Stanford’s Life Design Lab are good starting points to be familiarized with the idea of LXD and design thinking. The starter kit has been developed by the partnership of St. Petersburg College and Smart Sparrow, with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. It serves as an introduction to the concept with tools to utilize in classroom, case studies as examples, and publications regarding learning design. Interaction Design Foundation functions as a guide for technical skills to possess for designing better learning experiences. Finally, Life Design Lab of Stanford serves as an illustration of what LXD looks like in action. Additionally, Arizona State University’s Habitable Worlds is a good example regarding its leverage of adaptive technologies and aligning it with rich multimedia and hands-on experience.

It is plausible to assume that in the next five years or so, LXD will be more prevalent as both a profession and a line of research. Considering “two hands are better than one”, the collaboration of various fields and the power of technology can certainly be leveraged to drive educational change. One recommendation to consider for higher education institutions is to offer design thinking courses in educational disciplines at large. The more the students collaborate to solve real-life problems with their peers from various fields, the more possible it is to tackle educational problems and bring about change. In the professional field, on the other hand, institutions and independent designers alike can shift their professional development towards design thinking and collaborating across disciplines as well as designing more emotional, thus immersive “experiences” for learners.

References

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay.

Brown, T. (2009). Change by design: How design thinking transforms organizations and inspires innovation. New York: Harper.

Brown, T. & Katz, B. (2011). Change by design. The Journal of Product Innovation Management, 28(3), 381–383.

CAST (2018). The UDL Guidelines. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org/binaries/content/assets/udlguidelines/udlg-v2-2/udlg_graphicorganizer_v2-2_numbers-yes.pdf

Deaton, P.J. (2016). Accessible learning experience design and implementation. In F. H. Nah & C. H. Tan (Eds.), HCI in business, government, and organizations: Information systems: Third international conference, HCIBGO 2016 (pp. 47-55). Springer, Cham.

Dick, W. (1987). A history of instructional design and its impact on educational psychology. In J. Glover & R. Roning (Eds.), Historical foundations of educational psychology (pp. 183-202). New York: Plenum.

Floor, N. (2018a). Learning Experience Design.com. Retrieved from http://www.learningexperiencedesign.com/index.html

Floor, N. (2018b). What is Experience Design? Retrieved from http://www.learningexperiencedesign.com/learn-1.html

Gagné, R. M. (1965). The conditions of learning and theory of instruction (1st ed.). New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Glaser, R., Klaus, D. J. (1962). Proficiency measurement: Assessing human performance. In R. Gagné, (Ed.), Psychological principles in system development (pp. 421-427). New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Gustafson, K., & Bratton, B. (1984). Instructional improvement centers in higher education: A status report. Journal of Instructional Development, 7(2), 2-7.

Johansson-Sköldberg, U., Woodilla, J., Çetinkaya, M. (2013). Design Thinking: Past, Present and Possible Futures. Creativity and Innovation Management, 22(2), 121-146.

Kilgore, W. (2016). UX to LX: The Rise of Learner Experience Design. Retrieved from https://www.edsurge.com/news/2016-06-20-ux-to-lx-the-rise-of-learner-experience-design

Kimbell, L. (2009). Design practices in design thinking. European Academy of Management, 2009. Retrieved from: http://www.lucykimbell.com/stuff/DesignPractices_Kimbell.pdf

Mager, R.F. (1962). Preparing objectives for programmed instruction. Belmont, CA: Fearon.

Matthews, M.T., Williams, G.S., Yanchar, S.C., McDonald, J.K. (2017). Empathy in Distance Learning Design Practice. TechTrends, 61(5), 486-493.

Meyer, A., Rose, D.H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and Practice. Wakefield, MA: CAST Professional.

Milam, D., El-Nasr, M.S., & Wakkary, R., (2008). Looking at the Interactive Narrative Experience through the Eyes of the Participants. In Interactive Storytelling (pp. 96-107). Berlin: Springer.

Connell et al. (1997). The Principles of Universal Design. North Carolina State University’s Center for Universal Design, College of Design. Retrieved from https://projects.ncsu.edu/design/cud/about_ud/udprinciplestext.htm

Palmer, J., Caputo, A. (2002). The Universal Instructional Design Implementation Guide. Retrieved from https://opened.uoguelph.ca/instructor-resources/resources/uid-implimentation-guide-v13.pdf

Pandey, A. (2018, April 17). 10 Mobile Learning Trends for 2018. Retrieved from https://elearningindustry.com/mobile-learning-trends-2018

Reiser, R.A. (2001). A history of instructional design and technology: Part II: A history of instructional design. Educational Technology Research & Development, 49(2), 57–67.

Riverdale Country School and IDEO (2012). Design Thinking for Educators (2nd ed). Retrieved from http://www.designthinkingforeducators.com

Skinner, B.F. (1954). The science of learning and the art of teaching. Harvard Educational Review, 24, 86-97.

Trifecta Research (2015). Generation Z Media Consumption Habits: True Digital Natives. Retrieved from: http://trifectaresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Generation-Z-Sample-Trifecta-Research-Deliverable.pdf

Tyndale, E.,and Ramsoomair, F. (2016). Keys to Successful Interactive Storytelling: A Study of the Booming “Choose-Your-Own-Adventure” Video Game Industry. Journal of Educational Technology, 13(3), 28-34.

Wu, S. (2017, December 14). Is Design Thinking a Method of Design? Retrieved from https://uxdesign.cc/is-design-thinking-a-method-of-design-no-7c7fca1ba7c6

Correspondence concerning this chapter should be addressed to Ceren Korkmaz at korkmaz.11@ osu.edu