2 SHIFT: Learning Designers as Agents of Change

By Cara North

Introduction

Instructional design is an interdisciplinary field that has continued to grow in the last 50 years. With the rapid growth of instructional design, which has roots in military training, has come the prominence of technology. The role of the instructional designer has evolved, such has titles for them including learning designer, learning experience designer, and curriculum developers. In a society where content and technology are ubiquitous, learning designer’s roles in corporate and higher education are more critical than ever.

Like many in the profession, I fell into the role. After graduating college, I worked in a call center and was grateful to have employment in the recession. I was able to be promoted into the center into a role that introduced me to learning and development. Ten years later, I’m glad I found this interdisciplinary field. Throughout my career, I’ve seen many changes. Working in both corporate and higher educational settings, there has been a shift in the responsibilities and roles of learning designers. Learning designers now combine elements of graphic design, project management, computer science, education, communication, and more to create learning experiences for performance support.

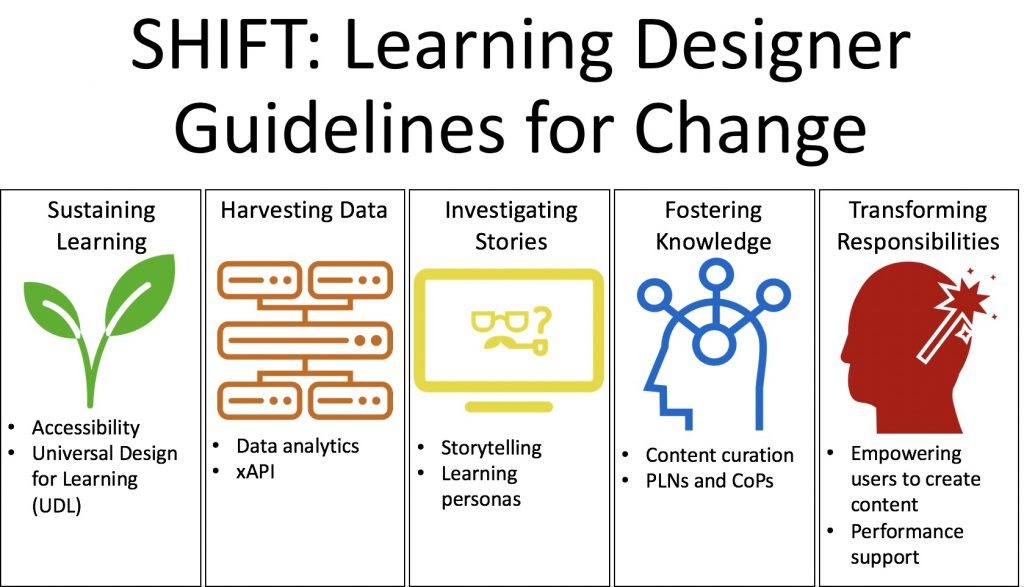

In many ways, learning and development professionals are agents of change. Change agents have many roles including developing a need for change, establishing an information exchange relationship and diagnosing problems (Rogers, 2003). Some of the ways this is happening is through the need to support learning with data, content driven by users, even the way we approach projects. To help learning and development professionals with these changes, I suggest a SHIFT in mindset. SHIFT is a set of guidelines and considerations learning designers should consider to be a catalyst of change in their organizations. SHIFT stands for Sustaining learning, Harvesting data, Investigating stories, Fostering knowledge and Transforming responsibilities. As technology continues to influence education and corporate learning, the learning designer must become an agent of change in order to provide learning experiences that prepare learners beyond the immediacy of the educational program. The learning designer has a responsibility to create experiences that set learners up for success to thrive in emerging roles and disciplines. This chapter will explore how learning and development professionals can leverage these areas of the discipline and explore how current professionals view these areas.

The SHIFT model

Sustaining Learning

The “S” in SHIFT stands for Sustaining Learning. Students and employees are becoming increasingly diverse in their learning needs. Enhanced diversity enriches learning and work environments due to a wide variety of perspectives, but it also emphasizes the need for learning instruction and materials to be inclusive of the needs of all learners (Kumar and Wideman, 2014). Students and employees want convenience when it comes to learning and development. This convenience means choices in the way they receive content including eLearning, blended, and face to face. A common criticism of eLearning in higher education and corporations is the amount of attrition and retention rates in online offerings versus face to face (Van Rooij and Zirkle, 2016). Often, common success criteria for learning is if a learner completed a course. This can be measured by their attendance in a face to face training or if they triggered a completion certificate in an eLearning course. Why would we want that to be a bar of success? Shouldn’t the bar be how the learner applied the information either on the job or in an academic setting? How do we know the learner retained any of the information if learning is a “one time” experience in a course versus an ongoing part of their development?

Where does this leave a learning designer? How can they provide learning in multiple modalities that is built for the enhanced diversity of the learning and work environments? Diversity in this case, is how you can create a learning environment that fits the needs of each person. Scott Cooper, published eLearning author and Vice President of Marketing for GO1, emphasizes for learning designers to have a big impact, they need to look beyond current learners.

“The most critical part of designing accessible learning is to look beyond our immediate users and think about how the wider organization may be using learning materials. This might mean that you need to expand on the concepts you are using to convey the learner, look into alternate delivery methods beyond your current capabilities, and research more about how ALL areas of the business go about learning rate than just creating one generic program for everyone to use” (S. Cooper, personal communication, March 24, 2018).

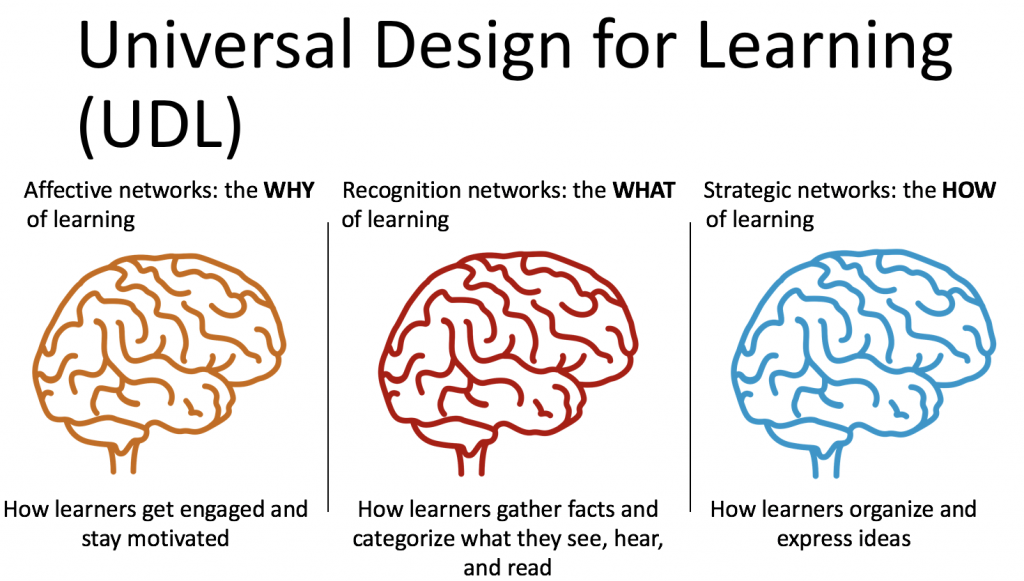

Accessibility can be difficult to define for learning and development professionals (Kumar and Wideman, 2014). Some of the reasons for the difficulty of defining accessibility includes the type of learning project, client and organizational budgets and scope, and the type of media used to build the learning project. A way that learning designers can plan for various audiences and modalities is by using Universal Design for Learning (UDL). UDL is a flexible and supportive framework for instructional design that helps plan accessible assessments, methods, materials, and learning objectives (Hall, Cohen, Vue, and Ganley, 2015). Figure 1 goes shares how the UDL framework is based in brain science and focuses on three networks.

Figure 1 – Universal Design for Learning (image adapted from: http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl/take_a_tour)

By creating learning experiences that consider all potential audiences, learning designers can work towards a sustainable learning ecosystem. What does learning and development currently look like at your organization? Is UDL a consideration? If it is not meeting the needs of multiple groups of learners, it may be time to SHIFT.

Harvesting Data

The “H’ in SHIFT stands for Harvesting Data. Data security and utilization are topics that learning designers should consider when creating learning interactions. For many years in eLearning, the way to obtain data is through Learning Management Systems (LMS) tracking the data through Sharable Content Object Reference Model (SCORM). By utilizing a LMS and SCORM, this adds a considerable cost to learning and development (Wang, Woo, Quek, Yang, and Liu, 2012). With added costs and a system that is not flexible, many learning designers are turning to xAPI. xAPI stands for Experience API which is an eLearning software specification that makes it possible to collect data about the learning experience outside of SCORM. In other words, it opens the possibilities of publishing learning objects outside of a LMS and tracking multiple types of data.

By using xAPI, learning data now is more robust and complete. Throughout the history of eLearning and with the rapid rise of eLearning Authoring tools such as Adobe Captivate and Articulate Storyline, learning designers have added quizzes and knowledge checks to modules. Once a learner completes these assessments and receive a certain score, they complete the module. This is the type of data that is usually gathered from the learner. In learning and development, many learning designers evaluate their learning impact by the Kirkpatrick Model of Evaluation. The Kirkpatrick model has four levels of evaluation in which the complexity of the behavioral change increases as evaluation strategies ascend to the next level (Moldovan, 2016). According to Myra Roldan, a Senior Instructional Designer at Amazon.com, not many learning professionals collect data beyond traditional Kirkpatrick Model Level 1 reactionary and Level 2 quiz-based learning assessments of their courses. There are many reasons for this including work load, organizational factors, and project costs. Regardless of the reason, only collecting this type of data from a learner makes it difficult to assess and validate the effectiveness of a learning solution or analyze the overall impact on employee performance.

With xAPI, learning professionals can mine and analyze online and offline learning data. Roland has used xAPI in augmented reality and Amazon Echo (Alexa Skills) applications. Here is how she defines and frames xAPI:

“Data is a compilation of opinions (subjective data) and facts (qualitative data). The Kirkpatrick Model (1) framework attempted to enable learning professionals to distinguish the type of data they collect about their courses. The problems is that we don’t do a very good job of it. xAPI is a framework that automates the data collection so can it can be analyzed, measured, and used to answer relevant business questions and evaluate outcomes. But we are still missing the mark because most learning professionals aren’t sure what data they should be collecting and then figuring out how to use that data to drive change in their organizations. Developing the ability to gather data from all available sources – traditional Level 1 and two assessments along with xAPI data, and analyzing and synthesizing that data is where the artwork begins. Learning Professionals can write a full story around their learning solutions, identifying gaps in curriculum, alignment to business goals, and overall ROI of their solutions just buy looking at all their data. This ability alone can change the way the business looks at learning and development and allow us to make decisions backed by data.” (M Roland, personal communication, March 24, 2018).

Soon, learning designers will not have to rely on pre-made tools and data collection methodologies. With xAPI and new ways of delivering curriculum, the only limitation to how the learner will experience the content is the limitation of the imagination of the learning designer. This continued use of learner analytic data can help learning designers create better learning experiences for performance and help their organizations change the way they approach learning.

Investigating Stories

The “I” in SHIFT stands for investigating stories. As content and information become more ubiquitous, learning designers need to find ways to create learning experiences that relate and resonate with learners. One way to do that is by using the power of storytelling. Multiple scholars have identified that storytelling is an effective instructional strategy for promoting learning motivations and improving the learning performance of students (Chung-Ming, Hwang, and Huang, 2012). Furthermore, storytelling can enhance memory by allowing learners to frame prior experiences and use them to bring the story to life. Stories give learners the power to put themselves in the shoes of the character and it can be a great methodology for content that require role playing such as soft skills.

Storytelling captures and moves people, which is why it is such a powerful tool for learning designers. Great stories prompt action, change minds, and foster learning curiosity. Put simply, stories make people care about the issue at hand. Story elements, when incorporated into eLearning, can improve learner engagement. Kim Lindsey, Senior Instructional Design Manager at Cinecraft shares why she uses storytelling in her instructional design methodology:

“Storytelling can have a tremendous influence to effect change. When well implemented, stories bring the content into the learner’s own experience, allowing risk-free practice for critical processes. The most effective stories come from the closest to the task: rank-and-file workers and learners who have attained the rank of “expert” not higher-level stakeholders. Learning designers, however, must consider that stories experts find interesting are often extreme outliers and are not helpful to novices. Balancing the needs of their target audience against the input of subject matter experts and the demands of stakeholders is always a challenge of learning designers” (K. Lindsey, personal communication, March 24, 2018).

Learning experiences should challenge the learner to think beyond their own reality. Stories are a great way to push your learners to think about situations and content in a different way. Stories can also come from your learners, which allows them to be a part of the learning process in a new way!

Fostering Knowledge

The “F” in SHIFT stands for fostering knowledge. With rapid changes in technology, leveraging technology to curate and funnel information is a great way to keep abreast with new developments. Developing a Personal Learning Network (PLN) can allow a learning designer to share information with peers. (Tour, 2017) defines PLNs as informal networks of teachers who interact online for professional purposes. Learning designers can cultivate PLNs by using tools such as Twitter or Yammer to connect with other professionals across the world. Another way learning designers can share knowledge is through communities of practice (CoP). Communities of practice are defined as groups of people who genuinely care about the same real-life problems or hot topics, and who on that basis interact regularly to learn together and from each other (Pyrko., Dörfler, & Eden 2017).

If learning designers use PLNs and CoPs to enhance their own professional development, they can also use them to establish thought leadership. By sharing ideas and collaborating with others, learning designers can share their expertise in certain aspects. Bethany Taylor, Global Digital Learning Advisor for COSTA has used both to not only grow in her own expertise but use it to demonstrate her skills.

“Learning is a tool that can be wielded by every person, but not every person knows how or has the innate desire. A learning designer is there to make learning easy to access, create connections and cultivate motivations. The only way a learning designer is going to be successful is to maintain their own learning. Through networks, communities, mentoring, chats, reading, or whatever else that may contribute to their learning: the learning designer should be fostering their own knowledge. Their motivation and excitement of continuous learning will trickle down to the people they aim to inspire and will incite internally motivated change.”(B. Taylor, personal communication, March 24, 2018).

Beyond the power of individual personal development for the learning designer is the ability to foster a culture of learning. Jo Cook, owner and virtual classroom expert of Lightbulb Moment understood the power of understanding resources and access are key to unleashing the power of learning.

“When I designed the Lightbulb Moment Community website about virtual classroom and webinar topics, I wanted it to enable people to change their own practice and support the change in others. To do this people coming to the free community would need to have access to knowledge in the forms of references, blogs, articles and more, as well as the discussions and other people contributing. One of the main elements in the design was to have categories that made sense to the topic (software/platforms, design, delivery) as well as levels of expertise (beginner, intermediate, advanced) so people could easily find what they wanted help on or share information about. From the organisation perspective, roles for supporting the community are essential. I had a Lightbulb Moment administrator who is the community manager, providing platform support, encouragement and linking people and questions together. I take the role of topic expert and I invited people I knew and trusted to be early adopters to get the community feel going and ensure that there was a vibrant conversation from the outset.” (J. Cook, personal communication, March 25, 2018).

Levering networks of knowledge and resources and curating these artifacts for their learners are skills learning designers who want to incite organizational change should do. It is imperative to model this behavior to inspire others to be curious and add to the knowledge base. Furthermore, the role of learning designers as knowledge gatekeepers are diminishing. More and more, knowledge is not treated as a currency in organizations and empowering learners to create content and share is a great way to foster change.

Transforming Responsibilities

Finally, the “T” in SHIFT is for transforming responsibilities. Looking at job descriptions for learning designers will show you that the amount of responsibilities they have are vast. From project management to graphic design, learning designers not only have a vast array of skills but also responsibilities. With the focus on learning design providing performance support to an organization, the power of the learning design to be a change agent is evident.

One way to own the change agent status is for a learning designer to flip the paradigm. Instead of thinking about themselves as the gatekeepers of knowledge, they should consider thinking of themselves as support pillars to learners. In other words, learning designers are not the only ones that can create content. By allowing users to create content, it brings a new element to the learning content that the learning designer can then refine and development. Sam Rogers, owner of SnapSynapse explains that a learning designer’s position in the organization can help bring a unique perspective to content.

“Learning and Development holds the keys to the kingdom. No other part of the organization has more insight into the problems of the employees, the flaws in the processes, the bugs in the systems, the quirks of the culture, or resistance of the entire organization to change. No other part of the organization is more critical to surviving change, or thriving within it. No other part of the organization is more directly responsible for attracting and retaining the very people who make or break the success of the organization: those who care enough to develop, to innovate, and to advance.” (S. Rogers, personal communication, March 25, 2018).

Learner generated content allows the learning designer to focus on what they do best: the process expert of crafting learning experiences. Regardless of where the learning designer is employed, at most organizations the content is the hardest part. By utilizing the talent of the organization and leveraging the expertise of those doing the work, more authentic learning experiences can be created.

Conclusion

Regardless of how you became a learning designer or your tenure, you have the capacity to be an agent of change for your organization. Perhaps you already are, but there is always room for improvement. By combining the elements of SHIFT (Figure 2) into organizational learning and development strategies, learning and development professionals can provide targeted insights into their corner of the institution. It also can help provide organizational leaders with the information they need to provide learning and development with the financial and organizational support to provide the best learning experiences to strengthen the organization.

Figure 2 – The SHIFT model.

SHIFT: Sustaining learning, Harvesting data, Investigating stories, Fostering knowledge and Transforming responsibilities. These guidelines allow learning designers to grow and take the skills they currently have and enhance them in multiple ways. All learning designers should be accountable to their organizations for assisting in performance support. Take a moment and evaluate your organization’s learning strategies. Do they focus on supporting the performance of the organization? Or do they need to SHIFT?

References

Catarci, T., De Giovanni, L., Gabrielli, S., Kimani, S., & Mirabella, V. (2008). Scaffolding the design of accessible eLearning content: a user-centered approach and cognitive perspective. Cognitive processing, 9(3), 209-216.

Chun-Ming, H., Hwang, G. J., & Huang, I. (2012). A project-based digital storytelling approach for improving students’ learning motivation, problem-solving competence and learning achievement. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 15(4), 368.

Cook, J. (2018, March 25). Personal interview with C. North.

Cooper, S. (2018, March 25). Personal interview with C. North.

Hall, T. E., Cohen, N., Vue, G., & Ganley, P. (2015). Addressing learning disabilities with UDL and technology: Strategic reader. Learning Disability Quarterly, 38(2), 72-83.

Kumar, K. L., & Wideman, M. (2014). Accessible by design: Applying UDL principles in a first-year undergraduate course. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 44(1), 125.

Lindsey, K. (2018, March 24). Personal interview with C. North.

Moldovan, L. (2016). Training outcome evaluation model. Procedia Technology, 22, 1184-1190.

Pyrko, I., Dörfler, V., & Eden, C. (2017). Thinking together: What makes Communities of Practice work? Human Relations, 70(4), 389-409.

Rogers, E.M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations (5th edition). New York: Free Press.

Rogers, S. (2018, March 25). Personal interview with C. North.

Roldan, M. (2018, March 24). Personal interview with C. North.

Taylor, B. (2018, March 24). Personal interview with C. North.

Tour, E. (2017). Teachers’ personal learning networks (PLNs): exploring the nature of self‐initiated professional learning online. Literacy, 51(1), 11-18.

Van Rooij, S. W., & Zirkle, K. (2016). Balancing pedagogy, student readiness and accessibility: A case study in collaborative online course development. The Internet and Higher Education, 28, 1-7.

Wang, Q., Woo, H. L., Quek, C. L., Yang, Y., & Liu, M. (2012). Using the Facebook group as a learning management system: An exploratory study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(3), 428-438.

Acknowledgements

This chapter features quotes from learning and development professionals across the world. We thank our colleagues Scott Cooper, Myra Roldan, Kim Lindsey, Bethany Taylor, Jo Cook, and Sam Rogers whose provided insights and expertise greatly assisted in the development of this chapter, although they may not agree with all the interpretations/conclusions of this section.

Correspondence concerning this chapter should be addressed to Cara North at north.129@osu.edu