Chapter Two: Faith and Religious Identity

Islam in Middle Eastern Societies

The Muslim populations of the Middle East make up only 44% of the total world Muslim population of the world (see “Muslim-Majority Countries of the Middle East” chart). A basis for understanding the role of Islam in Middle Eastern societies, is the distinction between its doctrine and the cultural practices which are done in the name of Islam or which informed them, historically. An effective way to bring out contrasts is to compare Islam with Judaism and Christianity. At the same time there are many aspects they share which are rooted in the same cultural milieu. We recommend reviewing the comparison chart comparing the Abrahamic religions again after reading this section.

In Islam, as in Christianity and Judaism before it, there are two distinct realms for religious oversight:

- faith and worship (ibadat).

- temporal and worldly activity (mu’amilat).

Islamic law, or the shar‘ia, is a system of theological exegesis and jurisprudence which covers both areas. Thus it guides the religious practices of Muslim communities, and also may serve as a basis for government as it did in Islamic empires of the past and a handful Muslim states of the present, such as Saudi Arabia. Once the modern nation state became the norm for government in most Muslim-majority countries shar ‘ia took a different kind of role in Muslim society, as states favored Western-style government and constitutional democracy. Secular states encouraged a more private practice of Islam.

Shar’ia remains an important guide to daily life for many Muslims, but its legislation now resides outside of the legal system in most Muslim-majority countries, with differing levels of involvement and influence. In some cases shar‘ia has remained the state’s government and legal system, as in Saudi Arabia. In any Muslim community, however, Islam’s precepts for good conduct remain paramount. The Five Pillars provide a foundation for proper religious practice, and are as follows (in order of importance):

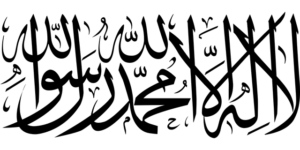

- Shahada, or Declaration of Faith;

- Salat, or Prayer (5 times daily);

- Saum, or Fasting (Especially During the Month of Ramadan);

- Zakat, or Alms (2.5% of one’s income should go to those in need, provided one has that much after meeting one’s own, one’s immediate family, and surrounding community needs);

- Ḥaj, or Pilgrimage (if one has the health and financial means, a Muslim is required to go to Mekka once in his or her lifetime, during the month of Ḥaj and perform a specific set of rituals).

In Islam, the only requirement to become Muslim is the first pillar; which is simply to utter the Shahada, or Declaration of Faith (translation, Payind): “I bear witness that there is no God other than the one God. I bear witness that Muhammad is the servant messenger of God.”

Beyond the Five Pillars, however, a moral life includes principles from the Qur’an and the example set by the prophet Muhammad which provide a moral foundation for the practices and laws which are intended to guide all facets of individual lives, families and society as a whole.

The Concept of Jihad

These principles for leading a correct life often require a moral struggle to achieve. This relates to a duty in Islam called jihad. The meaning of jihad is struggle – it can be internal and spiritual/moral, or external and physical/combat. Inner struggle is considered the “Greater Jihad”, or Jihad al-Akbar, due to its greater difficulty and greater importance in the life of a Muslim. Jihad al-Akbar is revered by Muslims. Jihad’s other meaning, related to war against an enemy, is the lesser jihad, or jihad al-Asghar. This is the struggle against injustice, oppression or invasion, and it allows the use of military force. Jihad al-Asghar possesses greater renown in the West, due to three powerful factors:

- Jihadi extremist groups in the news,

- European conflicts between Europe and what they called “Islamdom”, termed “Holy War” at the time (jihad continues to be translated as “holy war” for this reason).

- Stereotypes of Muslims as angry and violent aggressors pervade the Western knowledge base due to this history and the reinforcement of these images through various forms of media.

This list reflects the association which has developed in Western cultures between Islam and violence. Theologically, Islam’s orientation toward war is to minimize, and consider it as a last resort. The Qur’an expressly forbids needless killing:

“Because of this did We ordain unto the children of Israel that if anyone slays a human being-unless it be [in punishment] for murder or for spreading corruption on earth-it shall be as though he had slain all mankind; whereas, if anyone saves a life, it shall be as though he had saved the lives of all mankind. “ Qur’an, Surah 5, Verse 32, Pickthall translation

Islam doesn’t condone a passivist response to violence or injustice either. In this aspect, it differs greatly from Christianity’s precept to “offer the other cheek”. According to shar’ia, retaliation is acceptable, provided that it is and arbitrated decision, based on evidence, and it falls under one or more of the following categories:

- self defense.

- a response to an assailant of your family or community.

- apostasy, or treason (apostasy, or the relinquishing of the faith, has traditionally been considered a form of treason).