1 Chapter 1 – The digital divide and community college transfer students

Collins-Warfield, A., Marks, J.C., & Parker, D.J.

Introduction

This chapter explores the impact the digital divide has on institutions of higher education. Specifically, this chapter focuses on a diverse population — community college transfer students — and relevant initiatives that may help bridge the digital divide for them. This digital divide is approached from a critical lens which will be employed when addressing both digital literacy and access related initiatives.

The simplest explanation of the digital divide is the gap between those who do and do not have access to information technology and literacy in using it (Carvin, 2000). The concept of the digital divide as a civil rights issue emerged in the late 1990s when it became clear that those who did not have technology access and literacy would become marginalized (Carvin, 2000). As open enrollment institutions attracting students from a variety of educational and socioeconomic backgrounds, many community colleges are working on initiatives to support student success. This includes efforts to improve information technology access and literacy with the ultimate goal of preparing students for success in college and beyond. Online learning is one such initiative. While online learning has the potential to improve access and provide opportunities for students to increase their skills, there are limitations that can also reinforce existing inequalities.

This chapter explores the question, how can practitioners better understand the digital divide with respect to community college transfer students and what steps can higher education institutions take to aid in closing the gap? To address this question, the chapter begins with an exploration of the literature on community college students. This includes both demographic data as well as an assessment of the challenges they face. Next, the concepts of first-level and second-level digital divide are outlined, along with an explanation of how related concerns are manifested in higher education. The third section of the chapter delves into specific lessons learned from reviewing community college initiatives to support online learning. Finally, conclusions are drawn about how the digital divide may impact a community college student’s transfer experience, and suggestions are made for best practices by receiving institutions.

Identifying Community College Transfer Students and the Challenges They Face

This section reviews Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) and National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) data to aid us in better understanding who community college transfer students are as well as some of the challenges that they face. This will also include a review of the literature around community college transfer students to analyze what voices and supports are missing during conversations/initiatives around the digital divide.

The Importance of Community Colleges

Lichtenberger and Dietrich (2017) delved into the hierarchical nature by which higher education institutions are valued. Lichtenberger and Dietrich state that this hierarchy developed because of credentialism and exclusionary admission tactics rooted in historical and systemic educational inequity.

These factors have further exacerbated stigma around attending and supporting community colleges. Since community colleges serve such diverse populations, Lichtenberger and Dietrich encouraged institutions to challenge the notion that the community college resides at the bottom of the higher education pyramid. Some of the ways they can challenge are to create bridge programs that aid in degree completion, increase social and cultural integration, and support embedded advising (p. 25). Although institutions may struggle to support diverse populations holistically, Lichtenberger and Dietrich’s research shows that community colleges are in demand because of their accessibility but must also be responsive to those they serve.

Although community colleges have experienced historical challenges related to the decline in state appropriations, affordability, and academic rigor, students who apply to and attend community colleges still expect, and deserve, quality in instruction, transferability of coursework, and affordability (Barreno & Traut, 2012). Regardless of how some may view or value community colleges, they are positioned as spaces to aid in the democratization of higher education because of their reach. Community colleges aid in increasing access and can directly impact one’s social mobility because of their transfer function (Laanan, Starobin & Eggleston, 2010). Community college administrations hold the responsibility to respond to the needs of larger percentages of students; institutions must address the areas in which specific and diverse student populations struggle to complete and persist. Some of the factors that institutions should consider which impact persistence or completion include first-generation status, racial/ethnic backgrounds, lower socioeconomic status, and level of high school achievement (Fong, Acee & Weinstein, 2018).

Community College Transfer Students

This section expounds upon who community college students are. NCES data is utilized to explain this population is very diverse but focuses in on underrepresented and minoritized populations that are in need of extra support to increase completion rates. This section also delves into demographic data of community college transfer students and the challenges they face before, during, and after transferring to a four-year institution.

Community college transfer students are a significant and important population of focus because more students are beginning or continuing their academic journey at community college. Per the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC), community colleges serve a large percentage of the enrolled student population. “Among all students who completed a degree at a four-year college in 2015–16, 49 percent enrolled at a two-year institution in the previous 10 years” (National Student Clearinghouse, 2017). Between the 2005-2006 to 2015-2016 academic years, community colleges prepared or served nearly half of the undergraduate population that received bachelor’s degrees in 2015-2016. NSC continues to touch on the impact community colleges have on higher education by sharing that of former community college students who earned a bachelor’s in 2015–16, only 22 percent were enrolled for one term. However, 63 percent were enrolled at a community college for three or more terms (National Student Clearinghouse, 2017).

Enrollment demographics continue to shift. This shift has occurred because access to higher education has increased for many diverse populations which include racial/ethnic background, first-generation status, socioeconomic status, and enrollment status. When it comes to choosing an institution, access and affordability remain factors during the decision-making process for many students. Per a report produced by the NCES, in the fall of 2017, 34 percent of undergrads attended a public two-year college. Seventeen percent of full-time undergrads attended public, two-year colleges. Fifty-eight percent of part-time undergrads attended public, two-year colleges (Ginder, Kelly-Reid & Mann, 2018). Per those data, more community college students study part-time. For this reason, greater focus should be placed on non-traditional community college students who must enroll part-time because of financial and family obligations. Subsequently, more support should be provided to non-traditional students who are underrepresented, to ensure students transfer and persist without enduring undue financial hardship due to extended completion time.

To delve further into demographic data, 44 percent of Hispanic students, 35 percent of Black students and 31 percent of white students enrolled at community colleges in the fall of 2017 (Ginder, Kelly-Reid & Mann, 2018). In addition to racial/ethnicity diversity, specifically, community college students are first-generation college students, from diverse income and socioeconomic backgrounds, are diverse in levels of academic preparation (which can impact completion rates), and attend at higher part-time rates (Karp, Hughes & O’Gara, 2010). To aid practitioners in supporting community college students, Barbatis (2010) created an emerging model from their research which aligns with the themes that impact the persistence of culturally diverse student populations. These themes include 1) precollege characteristics which include race, income/SES, goal orientation, and other factors, 2) external college support and community influence, 3) social involvement, and 4) academic integration. According to Barbatis, for academic achievement/education to truly act as liberation, or social mobility to manifest, students must not be forced to assimilate but should be encouraged and supported to develop as their authentic selves.

How Should Institutions Respond to the Challenges Community College Transfer Students Face?

In this subsection, we will unpack the challenges community college transfer students face which include, but are not limited to varying levels of academic preparation (Fong, Acee & Weinstein, 2018), college readiness (Schademan & Thompson, 2016), goal orientation & faculty interaction (Fong, Acee & Weistein, 2018; Mitchell & Hughes, 2014), and other non-academic factors (Walker & Okpala, 2017; Goldrick-Rab, 2010). A special focus will be placed on how institutions should respond knowing the challenges community college transfer students are bound to encounter. Lastly, the sub-section delves into transfer student retention in relation to the digital divide and online course work. This last section acts as a transition for the second section of this chapter which focuses in-depth on the digital divide.

I. Academic Preparation

Although research has shown that rigorous academic preparation leads to success in college (Porter and Polikoff, 2012), many students still do not have access to equitable secondary education. For this reason, academic preparation must be unpacked to expose the inequities that many students are faced with before applying to and enrolling at community colleges. Although higher education often views itself in a silo, scholars and practitioners must consider the following K-12 factors when assessing a student’s level of academic preparedness. These factors include, but are not limited to, teacher preparation/development, rigorous academic preparation and curriculum opportunities, access to necessary materials and technology, and the impact of high stakes testing on student achievement (Hallett & Venegas, 2011). After completing community college placement examinations, the academic preparation gap is usually bridged via developmental coursework. Institutions must work to erase the punitive nature of developmental education courses because students typically do not receive college credit for and must take these courses before entering major coursework (Barbatis, 2010). Other scholars remind practitioners that students who fail to exit developmental coursework have a higher likelihood of unsuccessfully transferring and attaining a credential (Bailey, Jaggars, & Cho, 2010).

II. College Readiness

Schademan and Thompson’s (2016) qualitative study delved into student and faculty fixed and growth mindsets about college readiness. First-generation, low income (FGLI) students arrive at college with varying levels of academic and social preparation. Researchers found that when faculty believed that they could and actually served as cultural agents for FGLI students, students felt more supported and became more academically prepared. For this reason, institutions should invest in the cultural competence development of faculty and staff so they can provide meaningful support to students. The impact of growth-oriented faculty and staff directly connect to a student’s likelihood of transferring out and decreasing effects of the digital divide. The authors echo other scholars and suggest that more effective first-year experience/retention programs could aid in preparing students and campus communities to better support community college transfer students.

III. Goal Orientation & Faculty Interactions

In line with the impact of faculty, one method the researchers encourage is the implementation of new student programs and professor engagement. Their research showed that these interventions would help students identify their beliefs and goals toward learning. If their beliefs and goals are identified, students may be better equipped to persist with guidance. This person-centered approach allows institutions to meet the unique needs of each student (Fong, Acee & Weinstein, 2018).

Another method an institution can employ to ensure persistence includes meaningful faculty interactions. Mitchell and Hughes (2014) delved into the ways in which intentional and meaningful faculty interactions specifically impact minoritized community college student persistence. The authors offered strategies for students and faculty alike. Attention should be paid to male students, student-parents, and student unfamiliar with the collegiate culture.

IV. Non-academic factors and approach

Walker and Okpala (2017) discussed transfer students’ barriers to matriculation. They stated that transfer student barriers include non-academic factors that connect back to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

In their research, Walker and Okpala highlighted the voices of students and what they believe administrations should do to alter/develop policies and procedures so diverse transfer student needs are met. Some of these improvements include creating a sense of belonging for transfer students, providing quality advising, offering more recognition and acknowledgment, and providing orientation and extra time to orient to their new environment. Institutions should conduct assessments to not only determine what students need but to gauge needs directly from the population of focus.

Goldrick-Rab (2010) examined academic and policy research to determine what is known about the challenges community college students face from the macro, institutional, and social, economic, attributes levels. Goldrick-Rab stated that community college student success should be evaluated utilizing “frameworks that are capable of both estimating and explaining impacts” (p. 458). Goldrick-Rab found that based on the information we know, institutions must address issues that may impact students from a multifaceted approach where they accommodate diverse student needs. The author confirmed that any type of approach must be inclusive and multi-faceted to meet the needs of community college transfer students.

V. Transfer student retention

This section focuses on three retention efforts that will help transfer institutions support the retention and completion of community college transfer students. These efforts are: 1) improvements to systems that aid in the transference of coursework, 2) the need for culturally competent computer literacy examinations and 3) the importance of culturally competent online courses.

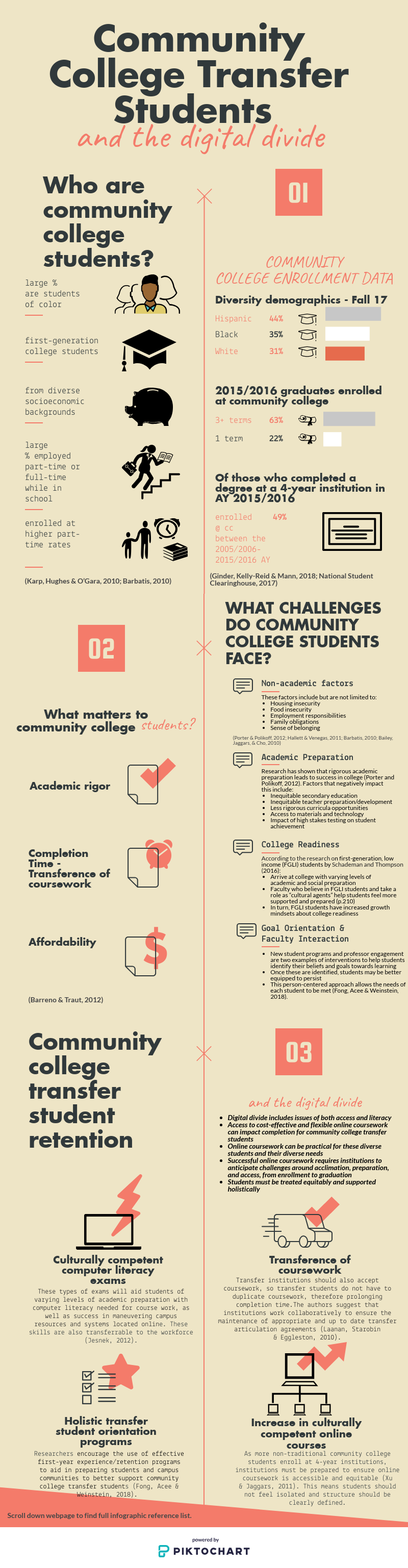

Visual Summary

The following infographic provides a visual representation of community college student traits.

Community College Transfer Student Infographic

What is the Digital Divide

What is the Digital Divide

Introduction

The Pew Research Center’s Internet and Technology project provided survey data showing that, in 2000, only 52% of American adults used the Internet—meaning that 48% did not—and that only 1% of American adults had broadband Internet access in their homes—meaning that 99% did not (Pew Research Center, 2018). In the most general sense, these statistics highlight what is known as the “digital divide”: a discrepancy that exists in access to, use of, and fluency with technology and digital tools that emerges between—and within—countries, and between specific groups of people within countries (Kady & Vadeboncoeur, 2019). As Cohron (2015) noted, “[f]rom the very beginnings of the rise of Internet usage in the mid-nineties, references to the digital divide have been prolific in research across numerous fields and professions that have strong ties to technology and information” (p. 77).

For a global picture of what the digital divide looks like, please view the following TED Talk featuring Aleph Molinari discussing the Learning and Innovation Network, from 2011:

As research has continued over the past two decades, the digital divide has been broken into multiple levels. Even at the turn of the century as access to (and use of) the Internet was in earlier stages of proliferation, scholars and researchers were delineating between costs of access (“technological access”) and skills and expertise in using the Internet (“social access”) (Bucy, 2000, p. 50). Over time, these delineations have come to be known as the first-level digital divide and the second-level digital divide respectively. More recently, a third-level digital divide has been identified to reflect outcomes of Internet use (Scheerder, van Deursen, & van Dijk, 2017).

First-level Digital Divide

Initially, the study of the digital divide centered mainly on access to the Internet (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2019). As early as the mid-1990s, the Commerce Department’s National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) collated survey data on telephone/modem access as well as PC ownership. Their data indicated that “information ‘have nots’” (n.p.) were disproportionately found in rural areas as well as urban areas, but the common thread was lower SES/income level (NTIA, 1995). In addition, NTIA found that: “[g]enerally, the less that one is educated, the lower the level of telephone, computer, and computer-household modem penetration” (1995, para. 9). The Pew Research Center has continued to gather survey data from 2000 to the present, and their findings have illustrated that the first-level digital divide can be further broken down into several identifiers: age, socioeconomic status (SES) or income level, educational attainment, community type/location, and ethnicity (Rainie, 2013; Pew Research Center, 2018).

At the highest level, the first-level digital divide can best be illustrated using United States Census Bureau data showing the breakdown in percentages of households (by state) with broadband Internet access:

Figure 1: The Digital Divide: Percentage of Households With Broadband Internet Subscription by State. 2015 American Community Survey. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2017/comm/internet-map.html

For a more complete picture of first-level digital divide data, watch the video below (created by chapter co-author, Daniel Parker).

As the video illustrates, while access to the Internet overall has increased, the first-level digital divide can still be seen. Drilling down to the more granular levels, while Pew’s survey data showed that these identified gaps in access level have narrowed over time, they continued to illustrate discrepancies in access to the Internet while also showing that some subgroups are seeing the gap close more slowly than others (Pew Research Center, 2018). Specifically, in their survey data based on racial identity, Pew found that, as of 2018, white, black, and Hispanic adults in the United States have nearly equal use of the Internet, based on percentage. This is reflected in Table 1.

| Racial Identity | 2000 | 2010 | 2018 |

| White | 53% | 78% | 89% |

| Black | 38% | 68% | 87% |

| Hispanic | n/a | 71% | 88% |

However, in other areas, such as income level, education level, and community, these gaps are closing more slowly, or hardly at all (Pew Research Center, 2018). This is reflected in Tables 2, 3, and 4, and these uneven percentages of Internet usage play a role in the developing second-level digital divide.

| Income Level | 2000 | 2009 | 2018 |

| Less than $30,000 | 34% | 60% | 81% |

| $30,000-$49,999 | 58% | 79% | 93% |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 72% | 92% | 97% |

| $75,000+ | 81% | 95% | 98% |

| Education Level | 2000 | 2009 | 2018 |

| Less than high school graduate | 19% | 40% | 65% |

| High school graduate | 40% | 68% | 84% |

| Some college | 67% | 87% | 93% |

| College graduate | 78% | 94% | 97% |

| Community | 2000 | 2009 | 2018 |

| Rural | 42% | 68% | 78% |

| Sub-urban | 56% | 76% | 90% |

| Urban | 53% | 73% | 92% |

Even as access to the Internet has become more ubiquitous in the U.S., the first-level digital divide is still a concern. Given that SES and income level are large factors in Internet access (US Census Bureau, 2013; Pew Research Center, 2018), material access remains an area of consideration given the requirements and costs of device purchase and maintenance and software purchase or subscription (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2019).

Second-level Digital Divide

As technology has continued to develop and evolve, and countries such as the U.S. have seen more widespread availability and adoption of the Internet, researchers moved away from the notion that access to technology and the Internet would automatically deliver the benefits of those tools to the end use (Scheerder, van Deursen, & van Dijk, 2017). The focus of digital divide study has thus broadened to include technological fluency, namely the attainment and practice of technological skills. This is referred to as the second-level digital divide (Hargittai, 2002; Ferro, Helbig, & Gil-Garcia, 2011; van Deursen & van Dijk, 2019).

van Deursen and van Dijk (2011) cited the shifting of society and culture to a more digital world, and this shift requiring the advancement of new technological skills (p. 894). Ferro, Helbig, and Gil-Garcia (2011) included the digital divide as an important cog within the globalization of societies and economies and note that “Information Technology (IT) literacy is seen as both a determinant of the digital divide and as a divide itself” (p. 4).

What is the framework for these skills? Mossberger, Tolbert, and Stansbury (2003) concluded that the second-level digital divide consists of the knowledge of and ability to use IT effectively, which includes not only technical fluency (the ability to functionally use technology) but also informational literacy (the ability to know when specific information has problem-solving relevance).

In additional research, comparative research survey data indicates that many of the identifiers distilled in first-level digital divide research again come to the fore as determinants for second-level digital divide (Büchi, Just, & Latzer, 2016). In addition, Büchi, Just, and Latzer, (2016) noted: “widespread Internet access does not correspond to equality in usage” (p. 2717).

This indicates that bridging the digital divide isn’t simply about access, and that demographic delineations permeate more than just the access part of the digital divide problem. This more layered view advocates that “individuals and communities employ technologies for very specific goals, linked often to their histories and social locations” (Hines, Nelson, & Tu, 2001, p. 5, as cited in Ferro, Helbig, & Gil-Garcia, 2011, p. 4).

The Digital Divide and Higher Education

In the higher education space, the digital divide manifests in both first- and second-level ways, and the first-level divide concerns can exacerbate the second-level divide. These concerns include: access to—and the ability to adequately process—information about colleges and admissions and financial aid processes, understanding technology in the higher education context, and the empowering of community college students to achieve educational goals.

College Choice

Arguably the most important step in becoming a college student is deciding on an institution. College choice is driven by access to information and the ability to interpret that information (Brown, Wohn, & Ellison, 2016). The college-choice process has largely moved online over the last decade, and this presents both first- and second-level digital divide challenges for disadvantaged families (Daun-Barnett & Das, 2013). Following assumptions from data about the access and engagement of low-income families with the Internet and e-commerce, these families would also be less likely to engage in college choice materials and processes that have moved online thus solidifying existing SES-based college participation gaps (Daun-Barnett & Das, 2013).

In addition, this first-level digital divide concern feeds the second-level digital divide as well. Daun-Barnett and Das (2013) contended that:

“[T]he digital divide in the college-choice process is a consequence of the sheer volume of resources available to students and parents and the increasingly difficult task of sorting these resources, judging the quality of those tools, and finding the right information – particularly for low-income, first-generation, and under-represented minority students” (p. 114).

A report from the University of Southern California’s Pulias Center for Higher Education argued that “digital tools are [not] a panacea for ensuring that low-income students receive adequate college guidance” (p. 4).

In some cases, because of digital divide concerns, college access may be even more difficult now for disadvantaged students even despite the wealth of information available in the digital space (Fleming, 2012). From standard application sites to services that allow for searching and matching up of students and institutions—including financial aid—those without adequate access to, and the skills to adequately utilize, technology are at a disadvantage (Fleming, 2012).

Many universities require management of course enrollments, applications for financial aid, and access to general announcements and information all be online, though there are generally no technological prerequisites for college admission and enrollment (Goode, 2010). Brown, Wohn, and Ellison (2016) also noted that there is a difference between the availability of information online and the understanding of that information, particularly for high school students unfamiliar with the experience of higher education, and that this can be amplified in low-income communities and families with no prior college attendees as there is less available experiential knowledge (p. 105).

Financial Aid

As more and more resources migrate online, access becomes more crucial, especially for resources that were no longer offered in the traditional sense. Around the turn of the century, the Student Financial Assistance division of the U.S. Department of Education (SFA) undertook a modernization of its processes (Jackson, 2003). Driven in large part by cost, Jackson (2003) raised the concern that such changes might not take the interests of those without adequate access to technology into account (p. 22). Jackson (2003) also wondered: “How can the federal government provide services using technology and simultaneously ensure equal quality of services for all citizens?” (p. 22).

In addition, while students aren’t required to use the online form for the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and can instead send in a paper form, students who complete the form online tend to get a faster response and decision (Venegas, 2006). This is another example of a deficit of service because of unequal access to technology, and Venegas (2007) noted that “this disparity in access is becoming increasingly disadvantageous for low-income students” (p. 142). And, the skills and support required to complete such applications may also lag for those on the wrong side of the second-level divide (Venegas, 2006).

Community College Students

In reference to the population of community college transfer students, the digital divide does not end once they reach higher education. The same issues of access to college choice information can continue to be a barrier for those looking to transfer (Fairlie & Grunberg, 2014). A small-sample study of community college students given free computers showed a modest increase in the enrollment into transferable courses, though the evidence was less clear about actual transfer data (Fairlie & Grunberg, 2014). In a similar study, Fairlie and London (2012) found small-sample evidence that a free computer for home use for low-income community college students produced slightly improved educational outcomes. Further, Goode (2010) cited the movement of library resources, including research databases, as well as learning environments online and states: “Knowing how to utilize the technological ecosystem of university life is certainly critical for academic success” (p. 498).

Jesnek (2012) cited “a wave of ‘non-traditional’ students” defined as “over the age of 25 who are often first-generation college enrollees, displaced from their previous careers due unforeseen layoffs, or desperate to update their résumés by earning an advanced certification or degree in order to ensure job security” (p. 1), and notes that this wave more directly affects community college enrollments. Jesnek also noted that one of the more consistent hurdles for this population is “technological ineptitude” (p. 2). While there may be an assumption that most “traditional” students will be comfortable with the expectation of using the Internet to obtain course materials, many “non-traditional” students “have not had the need or opportunity for using computers at any point in their lives—until they return to school” (Jesnek, 2012, p. 3).

Even as statistics indicate improvements nationally in first-level digital divide concerns, we can see that these issues are still relevant in the higher education context. And, in key areas such as college choice, financial aid, and the empowerment of disadvantaged students, second-level digital divide concerns remain prevalent and problematic. Institutions themselves, however, can take the lead in addressing these concerns, particularly in the context of online learning.

Overcoming Learning Challenges Using Technology: Online Learning

Before considering how to bridge the digital divide for community college students who are transferring to a different institution, it is necessary to review existing strategies for helping community college students achieve successful at their home institutions. Online learning is one method through which community colleges can help bridge the digital divide in terms of both access to education and development of technological literacy. In theory, online learning makes knowledge accessible to a broader audience, including those for whom distance, time, or cost prohibits traditional classroom learning. Yet online learning has its own flaws. This section will use a community college case study to highlight some systemic barriers to online learning. Specific community college initiatives to promote student literacy and fluency will then be reviewed.

Case Study: The Kentucky Community and Technical College System [KCTCS]

The Kentucky Community and Technical College System is considered to be an exemplar for using online learning to close the digital divide (Bailey, Vaduganathan, Henry, Laverdier, & Pugliese, 2018). KCTCS provided a case study for improving digital access and literacy. Research at KCTCS noted higher graduation rates for students who complete up to half of their classes online, versus students who enroll in strictly in-person coursework (Bailey et al., 2018). However, KCTCS students have a lower average pass rate in online classes than in in-person classes (Bailey et al., 2018). KCTCS began to offer online learning an an attempt to expand educational access and flexibility, especially for non-traditional learners (Bailey et al., 2018). In fact, the students who enrolled in KCTCS online courses “tend to be older (27% online versus 25% face-to-face), lower income (67% Pell online versus 60% face-to-face), and female (67% online versus 53% face-to-face)” (Bailey et al., 2018, p. 45). More than 60% of KCTCS students are Pell-eligible (Bailey et al., 2018, p. 19). To improve access for lower income students, online courses have lower costs per credit hour, and students who enroll in courses that do not follow traditional start and end dates can still qualify for financial aid. Additionally, KCTCS provided digital tutoring services, student coaches, and outreach software. Some of these resources were created and staffed by the institution and others are offered through third-party vendors (Bailey et al., 2018).

Online education at KCTCS was divided into two formats: learn by term and learn on demand (KCTCS, 2019a). Learn by term was structured in the traditional format for the academic term and was intended for students who have commitments and conflicts that prevent them from attending classes on campus (KCTCS, 2019b). The learn by term website clearly outlined requirements for success: computer and internet access, knowledge of basic computer skills, regular online communication, and ability to take tests and submit assignments online (KCTCS, 2019b). Learn on demand required similar access and skills for success. The primary difference is that learn on demand was structured to be completed at a student’s own pace, ranging from 6-15 weeks in length and beginning on a variety of start dates (KCTCS, 2019c). The learn on demand format provided further flexibility for students who may have competing commitments.

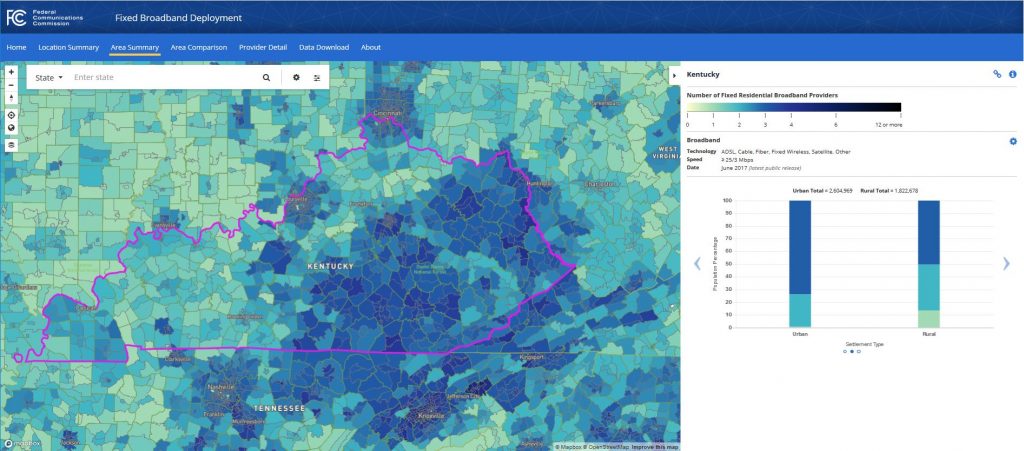

Initiatives like the KCTCS online programs are partially intended to support students who might be learning from home or are otherwise unable to attend classes in person on a college campus. They are intended to promote access and affordability. However, if as previously mentioned, students who live in a rural and/or less affluent area are much less likely to have reliable internet access at home (United States Federal Government, 2015). Less reliable internet access makes it more difficult to access course materials, download files, and submit assignments. Paradoxically, this potentially means that community college students who may most benefit from online courses may also be the least likely to have reliable internet to support their success in online learning environments. As referenced in Figure 1, according to the United States Census Bureau (2017), 61%-70.9% of households in Kentucky have broadband access, which places Kentucky in the bottom one-fifth of the entire United States. The broadband availability map for the state of Kentucky illustrates the discrepancy in broadband service across the state:

The geographical sections on this map are delineated as census blocks. The map illustrates the number of fixed residential broadband providers who offer a service with a download speed of 25mbps and an upload speed of 3mbps. Internet speed matters because it directly impacts one’s ability to download or stream content, view media, submit large files, and participate in chats or video conferences. Internet access at a speed of 25mbps/3mbps may be sufficient for video streaming and basic web conferencing, depending on what other devices in a household are utilizing the same service at the same time. However, although internet speed might be listed as 25mbps/3mbps, the provider is only guaranteeing the service will be up to that speed and not consistently at that speed. Depending on factors such as equipment quality — or even the weather for satellite-based services — the routine internet speed may be far below the level indicated by the provider.

Even assuming the advertised speed of 25mbps/3mbps is consistent, other factors influence a person’s ability to access this service. Using rural areas as an example, as indicated in the bar chart in Figure 2, almost half of residents are limited to only one (13.5%) or two (36.21%) internet service providers who offer this minimum download speed (Federal Communications Commission, n.d.). However, although the service is technically provided for that census block, it does not mean the service is physically available at every home, due to factors related to geography and infrastructure. It also does not mean that every person can afford the service. Additionally, with a lack of competition, the providers could potentially overcharge for the service, further impacting affordability and accessibility.

This map is intended to provide a basic illustration of how online learning, although well-intentioned, may not be a panacea for improving access and promoting technological fluency and literacy. There are concrete limitations to the accessibility of online learning. In the case of KCTCS, a lack of reliable internet access may contribute to the lower average pass rate for online courses (as described by Bailey et al., 2018). Even in cases where reliable internet service is available and accessing the materials for an online course is feasible, the issues of technological fluency and literacy are still at play. Creating equal access to learning technology does not imply students will have equal skill in using it (Toyama, 2015).

Strategies to Support Online Learning

It is no secret that many college students find the thought of online learning appealing. There are many practical reasons, for example, asynchronous coursework may be ideal for those who work full time. Yet students often have misconceptions about the rigor and requirements of online coursework. They may falsely assume online learning is easy. Students may also find it challenging to work with professors and classmates because their expectations about communication and procedures are based on their previous traditional, in-person learning experiences. A quick review of case studies related to community college online learning programs revealed three key considerations for supporting student success.

Assessing Whether Online Learning is the Right Choice

Institutions can provide better guidance in helping students decide whether an online learning format is appropriate for them. The Suffolk County Community College online education program set a good example for helping students assess their readiness for online education. On the front page of the online education website for Suffolk County Community College (2018), the format and expectations for online education were clearly and thoroughly explained. This website also incorporated an interactive questionnaire to help a student determine whether they will be successful in learning online. The questionnaire asked about access to software and the internet, ability to navigate software and websites, comfort with online learning modalities, and effectiveness of time management skills. Upon completion of the questionnaire, students received a recommendation as to whether they were ready for online learning, or if they needed to build additional skills. Students were also able to test their ability to navigate the learning management system by completing a practice module. In addition, Suffolk County Community College offered a concierge service, which is a telephone service staffed by current students. Students could call this phone number to receive immediate answers to questions related to online learning.

Westchester Community College (2019) also offered an interactive quiz that helps students assess their readiness for online learning. The quiz included questions assessing a student’s motivations and whether his or her expectations actually match a more traditional on-campus environment. In addition to producing a result that highlights whether online learning is the right choice, the quiz also included ample information to dispel common myths about online learning. Similarly, to promote informed decisions about online enrollment, Cuyamaca College (2018) included a video addressing myths directly:

Promoting Specific Strategies for Success

Institutions can also help students identify strategies for online learning success and connect students with tips and resources. Examples include Lincoln Land Community College (2019), which provided a list of recommended strategies and links to additional resources, and Oklahoma City Community College (n.d.), which outlined specific steps for success including managing email, reading the syllabus, and improving reading comprehension. Monroe County Community College (2019) offered a comprehensive series of web-based modules for students to review. The modules included: assessing readiness and aptitude for online learning; identifying personal learning styles; and exploring strategies for online success based on these learning styles.

Cuyamaca College participated in the California Community Colleges Online Education Initiative. According to the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office (2016), this initiative includes “an innovative set of interactive tutorials and tools, which may increase your chances of success in any online course” (n.p.). Students could browse through eleven interactive tutorials with subjects ranging from getting organized, managing time, financial planning, and finding personal support. The initiative also included links to interactive calculators and readiness tests.

Addressing Access Issues for Students from Lower SES Backgrounds

A variety of digital strategies could be utilized to improve access to and affordability of specific learning resources, which is especially important for students from lower SES backgrounds. One such strategy is Open Educational Resources [OER]. The Maricopa Millions project is a well-known example of OER. Maricopa County Community College District utilized learning resources that were copyright-free or were licensed under Creative Commons (2019b). Students were able to search for classes that offer “no cost or low cost (<$40) textbooks” (Maricopa Community Colleges, 2019a, para. 5). As a result, the Maricopa Millions has “saved students over 11.5 million dollars in the first five years” (Maricopa County Community College District, 2019b, para. 3). Closer to home, Columbus State Community College (2019) also offered access to OER materials to reduce learning costs.

Another strategy for promoting success in online learning for students from lower SES backgrounds is to provide students with free access to the technological tools they need. Greenfield Community College (2019) offered its students access to computers, printers, email, scanners, photocopiers, and video viewing. All library computers included standard hardware and software needed for academic success. Students were also eligible to borrow certain items on a short-term basis, including laptops, headphones, phone chargers, and external storage (Greenfield Community College, 2019). Additionally, adaptive technology was readily available for students with disabilities. This approach eliminated the need to personally own technology or internet access, assuming there are enough resources available for all students who need them.

Implications

Online education is one route for improving educational access and technological literacy for community college students. As students gain these skills, they may be better prepared to make a successful transition to their next institution. However, to begin to bridge any gaps in digital access and fluency, institutions need to consider several factors: the current (and future) composition of the student body and their unique needs; the school’s capacity for investing in digital technology, infrastructure, and tools; quality design of digital learning; and providing support for student success (Bailey et al., 2018, pp. 39-40). As some critics point out, if these factors are not carefully reviewed, online learning can become just another tool for reinforcing existing inequalities and stratification (Kim, 2018). The KCTCS online model served as an example of a successful approach for improving access to education, while also allowing students to develop critical technological skills. The other community colleges mentioned above also exemplified meaningful efforts to bridge the digital divide for community college students.

Students come to community college from a wide array of social identities, background experiences, and levels of academic preparedness. When a community college student transfers to another institution, the challenges they face can either be ameliorated or amplified. As a strategy for bridging the digital divide, online learning can help students gain important technological skills necessary for academic and professional success, in a format that overcomes barriers in terms of time, money, and physical presence. However, when a student lacks reliable access to the internet, online learning can reinforce existing inequalities. A student may earn lower grades or may fail to master content, both of which can result in the student being ineligible to transfer, or being inadequately prepared for academic success at their next institution.

Students who successfully complete online learning at a community college may bring to their new institution a set of academic and technical skills that will make them more likely to succeed, especially if the receiving institution also offers online coursework. However, the quality of online coursework can vary from institution to institution, depending on faculty training and preparedness to develop curriculum and implement effective pedagogical strategies (Kim, 2018; Toyama, 2015). An important step a receiving university can take to work towards the academic success of its transfer students is to ensure quality online learning experiences, which support and enhance the strides that have already been made to bridge the digital divide.

References for Chapter

Bailey, A., Vaduganathan, N., Henry, T., Laverdiere, R., & Pugliese, L. (2018, March). Making digital learning work: Success strategies from six leading universities and community colleges. Boston: The Boston Consulting Group. Retrieved from https://edplus.asu.edu/what-we-do/making-digital-learning-work

Bailey, T., Jaggars, S. S., & Cho, S.-W. (2010, February). Exploring the gap between developmental education referral and enrollment. Paper presented at the Achieving the Dream Strategy Institute, Charlotte, NC.

Barbatis, P. (2010). Underprepared, ethnically diverse community college students: Factors contributing to persistence. Journal of Developmental Education, 33(3), 16-26.

Barreno, Y., & Traut, C. A. (2012). Student decisions to attend public two-year community colleges. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 36(11), 863-871.

Brown, M. G., Wohn, D. Y., & Ellison, N. (2016). Without a map: College access and the online practices of youth from low-income communities. Computers & Education, 92-93, 104-116.

Büchi, M., Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2016). Modeling the second-level digital divide: A five-country study of social differences in internet use. New Media & Society, 18(11), 2703-2722.

Bucy, E. P. (2000). Social access to the internet. Harvard International Journal of Press-Politics, 5(1), 50-61.

California Community Colleges. (2016). Online student readiness tutorials. Retrieved from http://apps.3cmediasolutions.org/oei/students.html

Carvin, A. (2000, Jan/Feb). Mind the gap: The digital divide as the civil rights issue of the new millennium. MultiMedia Schools. Retrieved from http://www.infotoday.com/MMSchools/Jan00/carvin.htm

Cohron, M. (2015). The continuing digital divide in the united states. Serials Librarian, 69(1), 77-86.

Columbus State Community College. (2019, Feb 21). OER. Retrieved from http://library.cscc.edu/oer

Cuyamaca College. (2018 Jun 4). Online success. Retrieved from http://www.cuyamaca.edu/services/online-success/default.aspx

Daun-Barnett, N., & Das, D. (2013). Unlocking the potential of the internet to improve college choice: A comparative case study of college-access web tools. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 23(1), 113-134.

Fairlie, R. W., & Grunberg, S. H. (2014). Access to technology and the transfer function of community colleges: Evidence from a field experiment. Economic Inquiry, 52(3), 1040-1059.

Fairlie, R. W., & London, R. A. (2012). The effects of home computers on educational outcomes: Evidence from a field experiment with community college students. The Economic Journal, 122(561), 727.

Federal Communications Commission. (2016, June). Deployment: fixed broadband [interactive map]. Available at: https://broadbandmap.fcc.gov/#/area-summary?version=jun2017&type=nation&

geoid=0&tech=acfosw&speed=25_3

Federal Communications Commission. (2016, June). Speed: fixed broadband [graphic map]. Available at: https://www.fcc.gov/reports-research/maps/fixed-broadband-deployment-data/speed.html

Ferro, E., Helbig, N. C., & Gil-Garcia, J. (2011). The role of IT literacy in defining digital divide policy needs. Government Information Quarterly, 28, 3-10.

Fleming, N. (2012). Digital divide strikes college-admissions process. Education Week, 32(13), 14.

Fong, C. J., Acee, T. W., & Weinstein, C. E. (2018). A person-centered investigation of achievement motivation goals and correlates of community college student achievement and persistence. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 20(3), 369-387.

Furman, J., Black, S., & Shambaugh, J. (2015, July). Mapping the digital divide. Council of Economic Advisers Brief. Retrieved from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/wh_digital_divide_issue_brief.pdf

Ginder, S. A., Kelly-Reid, J. E., & Mann, F. B. (2018). Enrollment and Employees in Postsecondary Institutions, Fall 2017; and Financial Statistics and Academic Libraries, Fiscal Year 2017: First Look (Provisional Data) (NCES 2019- 021rev). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019021REV.pdf

Goldrick-Rab, S. (2010). Challenges and opportunities for improving community college student success. Review of Educational Research, 80(3), 437-469.

Goode, J. (2010). The digital identity divide: How technology knowledge impacts college students. New Media & Society, 12(3), 497-513.

Greenfield Community College. (2019). Computers, technology, and wireless internet. Retrieved from https://www.gcc.mass.edu/library/services/technology/

Hallett, R. E., & Venegas, K. M. (2011). Is increased access enough? Advanced placement courses, quality, and success in low-income urban schools. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 34(30), 468-487.

Hargittai, E. (2002). Second-level digital divide: Differences in people’s online skills. First Monday, 7(4). Retrieved from https://firstmonday.org/article/view/942/864

Hines, A. H., Nelson, A., & Tu, T. L. N. (2001). Hidden circuits. In A. Nelson, T. L. N. Tu, & A. H. Hines (Eds.), Technicolor (pp. 5). New York: New York University Press.

Jackson, C. (2003). Divided we fall: The federal government confronts the digital divide. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 33(3), 21-39.

Jesnek, L. M. (2012). Empowering the non-traditional college student and bridging the “Digital Divide”. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 5(1), 1-8.

Laanan, F. S., Starobin, S. S., & Eggleston, L. E. (2010). Adjustment of community college students at a four-year university: Role and relevance of transfer student capital for student retention. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 12(2), 175-209.

Kady, H. R., & Vadeboncoeur, J. A. (2019). Digital divide. Salem Press Encyclopedia. (online) Grey House Publishing.

Karp, M. M., Hughes, K. L., & O’Gara, L. (2010). An exploration of Tinto’s integration framework for community college students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 12(1), 69-86.

Kentucky Community and Technical College System. (2019a). KCTCS online. Retrieved from https://kctcs.edu/education-training/kctcs-online/index.aspx

Kentucky Community and Technical College System. (2019b). KCTCS online: Learn by term. Retrieved from https://kctcs.edu/education-training/kctcs-online/learn-by-term/index.aspx

Kentucky Community and Technical College System. (2019c). KCTCS online: Learn on demand. Retrieved from https://kctcs.edu/education-training/kctcs-online/learn-on-demand/index.aspx

Kim, J. (10 October 2018). Is technology driving educational inequality? Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from: https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/ blogs/technology-and-learning/technology-driving-educational-inequality

Laanan, F. S., Starobin, S. S., & Eggleston, L. E. (2010). Adjustment of community college students at a four-year university: Role and relevance of transfer student capital for student retention. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 12(2), 175-209.

Lichtenberger, E., & Dietrich, C. (2017). The community college penalty? Examining the bachelor’s completion rates of community college transfer students as a function of time. Community College Review, 45(1), 3-32.

Lincoln Land Community College. (2019). Strategies for online learning success. Retrieved from https://www.llcc.edu/academics/online/strategies-for-online-learning-success/

Maier, A. (2012). Doing good and doing well: Credentialism and Teach for America. Journal of Teacher Education, 63(1), 10-22.

Maricopa County Community College District. (2019a). Find your open educational resources. Retrieved from https://www.maricopa.edu/why-maricopa/maricopa-millions/find-oer-

courses

Maricopa County Community College District. (2019b). Making higher ed more affordable and accessible. Retrieved from https://www.maricopa.edu/why-maricopa/maricopa-millions

Mitchell, Y. F., & Hughes, G. D. (2014). Demographic and instructor-student interaction factors associated with community college students’ intent to persist. Journal of Research in Education, 24(2), 63-78.

Monroe County Community College. (2019). Online learning: Is it for me? Retrieved from https://www.monroecc.edu/depts/distlearn/information-for-students/mini-course-online-learning-is-it-for-me/

Mossberger, K., Tolbert, C. J., & Stansbury, M. (2003). Virtual inequality: Beyond the digital divide. Georgetown University Press.

National Student Clearinghouse (NSC). (2017, March). Snapshot report – Two-year contributions to four-year completions. Retrieved from https://nscresearchcenter.org/snapshotreport-twoyearcontributionfouryearcompletions26/

National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA). (1995). Falling through the net: A survey of the “have nots” in rural and urban America. Washington, D.C. U.S. Department of Commerce: Economic and Statistics Administration. Retrieved from: https://www.ntia.doc.gov/ntiahome/fallingthru.html

Oklahoma City Community College. (n.d.). Tips, ideas, and strategies for online students. http://www.occc.edu/online/tipsideasstrategiesforonlinecourses.html

Pew Research Center. (2018). Internet/Broadband fact sheet. Internet and Technology. Retrieved from: https://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/

Pew Research Center. (2019). College students and technology. Retrieved from https://www.pewinternet.org/2011/07/19/college-students-and-technology/

Porter, A. C., & Polikoff, M. S. (2012). Measuring academic readiness for college. Educational Policy, 26(3), 394-417.

Rainie, L. (2013). The state of digital divides [presentation]. Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/video/business/technology/pew-15-percent-of-americans-dont-use-the-internet/2013/11/06/172a067c-4698-11e3-bf0c-cebf37c6f484_video.html

Schademan, A. R., & Thompson, M. R. (2016). Are college faculty and first-generation, low-income students ready for each other? Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 18(2), 194-216.

Scheerder, A., van Deursen, A., & van Dijk, J. (2017). Determinants of internet skills, uses and outcomes. A systematic review of the second- and third-level digital divide. Telematics and Informatics, 34, 1607-1624.

Suffolk County Community College. (2018). Suffolk online. Retrieved from https://www.sunysuffolk.edu/explore-academics/online-education/index.jsp

Toyama, K. (3 Jun 2015). Why technology alone won’t fix schools. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/06/why- technology-alone-wont-fix-schools/394727/

United States Census Bureau. (2013). American Community Survey 1- year Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) files. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data/pums.html

United States Census Bureau. (2017, September 11). The digital divide: Percentage of households with broadband internet subscription by state [graphic map]. 2015 American Community Survey. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2017/comm/internet-map.html

United States Federal Government. (2015, July 15). [There is a digital divide in the United States] [Infographic]. Retrieved from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/share/heres-what-digital-divide-looks-united-states

University of Southern California. (2018). How is technology addressing the college access challenge? A review of the landscape, opportunities, and gaps. Pullias Center for Higher Education. Retrieved from https://pullias.usc.edu/download/technology-addressing-college-access-challenge-review-landscape-opportunities-gaps/

van Deursen, A., & van Dijk, J. (2011). Internet skills and the digital divide. New Media & Society, 13(6), 893-911.

van Deursen, A., & van Dijk, J. (2019). The first-level digital divide shifts from inequalities in physical access to inequalities in material access. New Media & Society, 21(2), 354-375.

Venegas, K. M. (2006). Low-income urban high school students’ use of the internet to access financial aid. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 36(3), 4-15.

Venegas, K. M. (2007). The internet and college access: Challenges for low-income students. American Academic, 3, 141-154.

Walker, K. Y., & Okpala, C. (2017). Exploring community college students’ transfer experiences and perceptions and what they believe administration can do to improve their experiences. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 65(1), 35-44.

Westchester Community College. (2019). Is online learning right for you? Retrieved from http://www.sunywcc.edu/academics/online-education/student-resources/is-online-learning-right-for-you/

Xu, D., and S. S. Jaggars. 2011. The effectiveness of distance education across Virginia’s Community Colleges: Evidence from introductory college-level math and English courses. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 33 (3): 360–377.

References for Infographic

Bailey, T., Jaggars, S. S., & Cho, S.-W. (2010, February). Exploring the gap between developmental education referral and enrollment. Paper presented at the Achieving the Dream Strategy Institute, Charlotte, NC.

Barbatis, P. (2010). Underprepared, ethnically diverse community college students: Factors contributing to persistence. Journal of Developmental Education, 33(3), 16-26.

Barreno, Y., & Traut, C. A. (2012). Student decisions to attend public two-year community colleges. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 36(11), 863-871.

Fong, C. J., Acee, T. W., & Weinstein, C. E. (2018). A person-centered investigation of achievement motivation goals and correlates of community college student achievement and persistence. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 20(3), 369-387.

Ginder, S. A., Kelly-Reid, J. E., & Mann, F. B. (2018). Enrollment and Employees in Postsecondary Institutions, Fall 2017; and Financial Statistics and Academic Libraries, Fiscal Year 2017: First Look (Provisional Data) (NCES 2019- 021rev). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019021REV.pdf

Hallett, R.E., & Venegas, K. M. (2011). Is increased access enough? Advanced placement courses, quality, and success in low-income urban schools. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 34(30), 468-487.

Jesnek, L. M. (2012). Empowering the non-traditional college student and bridging the “Digital Divide”. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 5(1), 1-8.

Karp, M. M., Hughes, K. L., & O’Gara, L. (2010). An exploration of Tinto’s integration framework for community college students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 12(1),

69-86.

Laanan, F. S., Starobin, S. S., & Eggleston, L. E. (2010). Adjustment of community college students at a four-year university: Role and relevance of transfer student capital for student retention. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 12(2), 175-209.

National Student Clearinghouse (NSC). (2017, March). Snapshot report – Two-year contributions to four-year completions. Retrieved from https://nscresearchcenter.org/snapshotreport-twoyearcontributionfouryearcompletions26/

Porter, A. C., & Polikoff, M. S. (2012). Measuring academic readiness for college. Educational Policy, 26(3), 394-417.

Schademan, A. R., & Thompson, M. R. (2016). Are college faculty and first-generation, low-income students ready for each other? Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 18(2), 194-216.

Xu, D., and S. S. Jaggars. 2011. The effectiveness of distance education across Virginia’s Community Colleges: Evidence from introductory college-level math and English courses. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 33 (3): 360–377.