5 Chapter 5 – Crowdsourcing: Trend or treasure?

Sanzone, J., & Walker, R.

Key Takeaways

In this chapter, we will be exploring the follow questions

- What are some prevalent or innovative ways that educators use crowdsourcing?

- What are some prevalent or innovative ways that students use crowdsourcing?

- What predictions can we make about the future of crowdsourcing in education?

In this chapter, we will address the varied uses of crowdsourcing by both educators and students within an online learning community. We will also briefly discuss the results of these crowdsourcing efforts, in terms of the effect on the learning environment and the individual goals of the teachers or students. Crowdsourcing is a well researched topic, especially if you include discovery or inquiry based educational methods. In this chapter we will focus solely on popular and innovative methods currently being used by educators. We will also use the definition of crowdsourcing crafted by Estellés-Arolas. and González-Ladrón-de-Guevara (2012) to discuss the future of crowdsourcing.

Crowdsourcing is such a huge buzzword, with a wide reaching definition, so to begin, we are going to spend a minute defining some terms and outlining the rest of this chapter. We have also included our sources here if you’d like to further your reading on this subject.

|

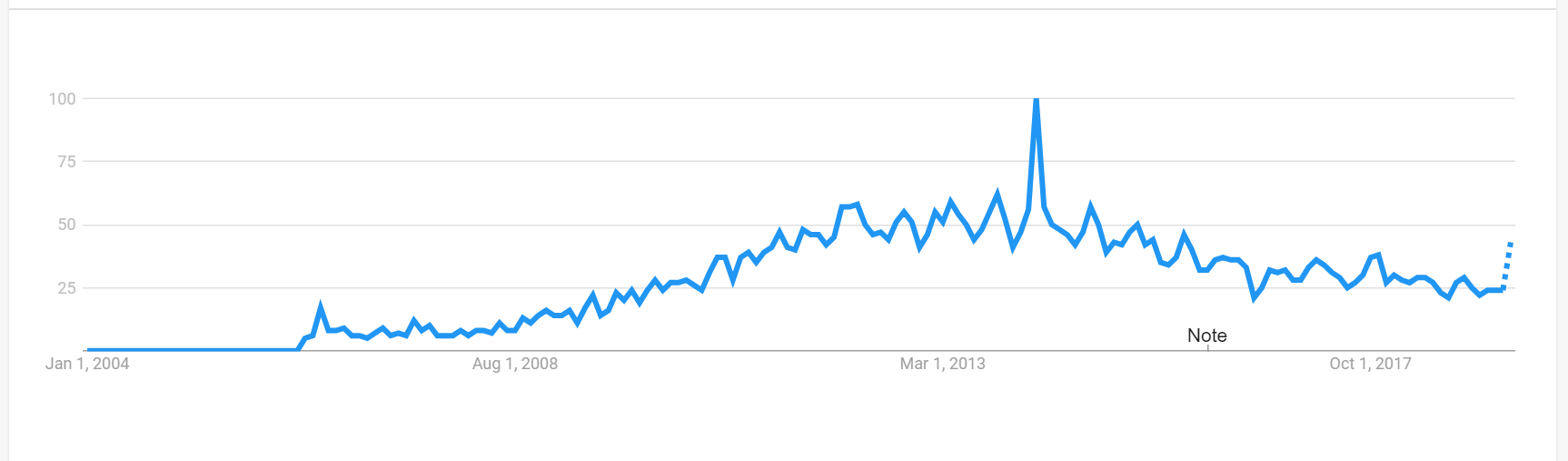

The Rise of Crowdsourcing

Over time, the concept of crowdsourcing has gained popularity. Although Llorente and Morant (2015) reference dates as early back as 1714 when the British government created a sort of crowdsourced competition where a prize would be awarded to whomever created the best method for measuring the longitude of a ship, the use of educational crowdsourcing is a much more modern concept. Examples include the launching of several digital platforms such as PlanetMath (2000), Wikipedia (2001), Peer to Peer University and Scitable (2009) and Skillshare and Duolingo (2012). Although the research on educational crowdsourcing is still developing, this analytic graphic on the concept of crowdsourcing shows how the use has developed over time, peaking recently, but with a projected increase going forward. The image below was taken from the Google Trends tool which shows how much buzz there is around a specific term in searches. In this case, the image represents the popularity of the search term “crowdsourcing.”

Crowdsourcing & Educators

“As teachers we frequently promote ourselves in our modern role as facilitators rather than knowledge owners and yet when we get into the classroom so much of what we do tends to be telling rather than asking.” (Peachey, 2017)

Using crowdsourcing strategies can challenge the traditional role of the educator to help them embrace being a facilitator in the physical and virtual classroom spaces. There are a variety of ways that educators today are using crowdsourcing to directly and indirectly inform their practice that connect with the own development and pedagogies that embrace the strength learners bring, both in their role as learners and in their individual skills and knowledge.

Pause and Consider

Consider your experience as an educator:

- What are crowdsourcing methods you have used with students in your learning environments?

- What are novel approaches you have seen colleagues implement?

- What have been some of the benefits of crowdsourcing for you as an educator?

What’s Happening Now

Similar to other professions, educators are using crowdsourcing techniques in preparation for their role in the classrooms. From crowdsourcing for their own professional development (Dunlap & Lowenthal, 2018) to using it to develop materials for teachers (Walker, 2019), instructors find this approach helpful for their own learning and development, broadly speaking. Additionally, there are a variety of ways educators use crowdsourcing techniques to inform how they approach classroom content development and adaptation.

Additionally, while Wilson (2018) found that crowdsourcing is used for curriculum development, Loewus (2013) affirms that teachers are actively rating and reviewing other’s lesson plans shared online, indicating they are not passively adopting content they find, but are giving careful consideration to how materials shared meet the learning needs of their students and style of their course. In the higher education sector, Llorente and Morant (2015) share this effort is often referred to as “crowdteaching” ad educators assemble a variety of sourced materials into a more cohesive curricular plan. While this term itself was not seen in literature for the K-12 sector, similar approaches and concepts are permeating that space. In fact, co-author for this chapter, Rachel Walker (2019) used crowdsourcing to co-create a variety of lesson plans, curriculum maps and test prep strategies for South Dakota classrooms, with teachers all over the state in collaboration with the K-12 Teach for American Program. Teach For America is an organization that pushes for more networking and collaboration between teachers. They have created numerous collaborative platforms where teachers can share, edit and co create documents relevant to their states standards.

Crowdsourcing materials for lectures provides a variety of benefits to the educator. It can make the lecturing process more efficient (Llorent & Morant, 2015), but it also allows instructors to be more interdisciplinary in their approach. For example, Amandolare (2009) highlighted that while many educators have a desire to integrate their subject matter with others, learning curricula outside of ones’ specialty isn’t always feasible. Crowdsourcing can make other subject matter more accessible for educators who wish to pull them together.

Not only can crowdsourcing be used to develop the framework for a course, but it can also be used to adapt material as instructors received feedback or insight into students’ ongoing development. This might be in a real-time format that calls on students to respond during staff time through platforms such as Tricider, Survey Monkey and Typeform (Peachey, 2017) or it might come between the development of sessions or modules to inform the future. Indeed, Kochsmider and Buschelf (2016) suggest one of the advantages of using crowdsourcing techniques is that educators are able to assess how well students understand the course content and can be responsive to their needs going forward.

Knowledge Production

One of the strongest benefits using crowdsourcing techniques is that it can allow learners to engage in knowledge production. A prime example of this includes Wilson’s (2018) usage of his classroom to engage learners in creating timelines of world events for a series of Latin American countries. (Wilson’s syllabus detailing the implementation for this project can be viewed at Matthew Charles Wilson’s 355 Syllabus. Another example, includes this eBook which was constructed by a group of learners with varying interests, skills and knowledge. These projects can come in the form of “debates and discursive essays, sharing resources, and planning an event” (Peachey, 2017) and might even involve inquiry and discovery based math and science projects using tools such Survey Monkey and buzz-in features on Ipads and laptops (Walker, 2019). While this chapter aims to share existing research regarding the use of crowdsourcing in education, it is also worth noting that crowdsourcing is also used to create research in addition to being the subject of it (Corneli & Mikroyannidis, 2012).

Peer Evaluation

Perhaps one of the more unique ways educators are using crowdsourcing is challenging the traditional teacher-learner hierarchy that is assumed in a traditional classroom setting. While sourcing information or lesson plans, projects, and research already defy the status quo, educators are also pulling students in to evaluate the work of their peers. At Duke University a project called “This is Your Brain on the Internet” seeks to connect students with the role of the instructor (Online Universities, 2010). In a variety of spaces, peers are asked to directly evaluate each other by completing an assessment about their peers, something that ensures reliability (Wilson, 2018), and also increases peer efforts (Amandolare, 2009). Slightly differently, Koschmider and Buschfeld (2016) offer an innovative approach where students are actually part of crowdsourcing efforts to design the exam and the solution key. While the instructor has an important role in oversight, this approach allows investment in the learning process, shifting expectations about who is learning from whom.

Systems and Policies

Unsurprisingly, crowdsourcing use by educators is not limited to individual classroom environments and can have an effect on larger systems. Indeed, Gee (2013) reported “crowdsourcing tools are slowly working their way into the education policy world, designed to give teachers and district employees more say on big decisions that affect their school environment.” In reference to issues in the California school districts, this crowdsourcing effort gave the opportunities for teachers, bus drivers, administrative staff and school counselors to provide their ideas (Loewus, 2013). As educators continue to be concerned about ensuring their voices are recognized, this approach is powerful in terms of their involvement being more than a symbolic nod to their requests, but also ensures educators in a variety of roles can lend their collective wisdom to tackling difficult dilemmas facing education.

Below is another great example of a similar approach taken in Amsterdam. Chris Sigaloff shares a story of how crowdsourcing an approach to tackle issues in their local education system creates a shared responsibility, establishes a kind of movement than transcends competition and ultimately helps to form a culture of innovation that welcomes those who would traditionally be outsiders and lends energy toward attacking larger systems of inequality.

Crowdsourcing & Students

There are a variety of ways that students of all ages participate in crowdsourcing behaviors. In some cases, these practices are a result of intentional educator pedagogy (as in many of the practices referenced in the previous section), but students also engage in self-directed crowdsourcing behaviors inspired by their own out of classroom navigation and peer influences. Admittedly, structured and intentional crowdsourcing practices are better documented in the literature base, but that does not mean that student-initiated crowdsourcing is any less powerful. The following are many of the ways in which students actively engage in crowdsourcing in an educational context.

Pause and Consider

Consider how crowdsourcing techniques might help you create a stronger learning environment for your students:

- What are the ways crowdsourcing creates more student engagement?

- How might crowdsourcing techniques build empathy between the experiences of students and educators?

- How would your classroom experience have been different as a student if your instructors implemented crowdsourcing techniques?

Students in the Driver’s Seat

Although students rarely use the word crowdsourcing as a part of what they do in the learning environment, they are regularly engaged in practices and activities that certainly align with previously established definitions. Most of these self-directed practices are not only unstructured by the classroom environment, but sometimes occur in contrast to the advice of their educators. Part of the reason this can occur is a mismatch in ascribed value to a variety of practices. Reynol Junco (2014) ascribes these differences as a clash between youth normative thinking and adult normative thinking. If there are generational differences between those in the role of educator and those in the student role (which there almost always are in K-12 education and sometimes are in higher education) then some practices students might use that become frowned upon by those employing adult normative thinking may go underground.

An example here includes Head and Eisenberg’s (2010) study about how students use Wikipedia. Often Wikipedia is vilified as a source that is unreliable and not worth using. This study, however, found a majority of students were using this source and just deciding not to disclose this on their reference list. Most were not taking facts directly from the source, but instead indicated it was useful in getting background or a quick summary to serve as primer for the rest of their research. In this case, students were using a source they were often advised to avoid because they felt like they needed to know something about a topic before they could even begin to talk with their professor about the subject.

Although this is a singular example of where students use self-directed crowdsourcing practices, there are many others that we know from practical experience. Students use a variety of social media tools to gather information and get different perspectives for educational purposes. Further, research and experience shows that Gen Z (students 22 and younger) are more likely to trust information coming from their peers than authority figures, such as educators and failure for educators to embrace this may exacerbate these separations.

Below is a great example of a video highlighting both high school teacher, David Preston and his former students, Trevor and Ian, who share examples of how they are “Hacking the Curriculum”:

https://vimeo.com/44276426

Teamwork Makes the Dreamwork

There are several ways students actively engage in crowdsourcing through structured educator facilitation. In fact, Corneli and Mikroyannidis (2012) suggest the importance of facilitation as peer learning itself is not enough to ensure a successful and positive learning environment. Depending upon the make-up and structure of the classroom facilitators can help build a sense of comraderie and commitment and work to keep students engaged with their peers.

One significant way that students can engage with crowdsourcing through the facilitation of the instructor is in working together to complete a joint project. Called “crowdlearning”, students are expected to share and teach each other by leveraging their individual and unique skills (Llorente & Morant, 2015). Examples of this practice include our work on creating this eBook and individual eChapters as well as the example from Preston’s video where students worked together to create a MindMap that individual would have taken a longer period of time and only accounted for a single perspective.

Another significant way students engage with structured crowdsourcing can be through creation and execution of assessment tools. While Llorente and Morant (2015) focus on more traditional peer assessment efforts (such as the feedback we provide each other on our eChapters), there are also some pedagogies that engage students in evaluation in a more depth way. A great example is Kochmider and Buschfeld (2016) who actually worked with students to develop questions and solutions for exams that all students would take. By creating this pool of exam questions, carefully considering what would be constitute a correct answer, and preparing for the exam themselves, students not only had the opportunity to engage in active learning practices, but also played a role in shaping the achievement of themselves and their peers. The video above also shows a great example of Trevor and Ian showing their peer assessment interface.

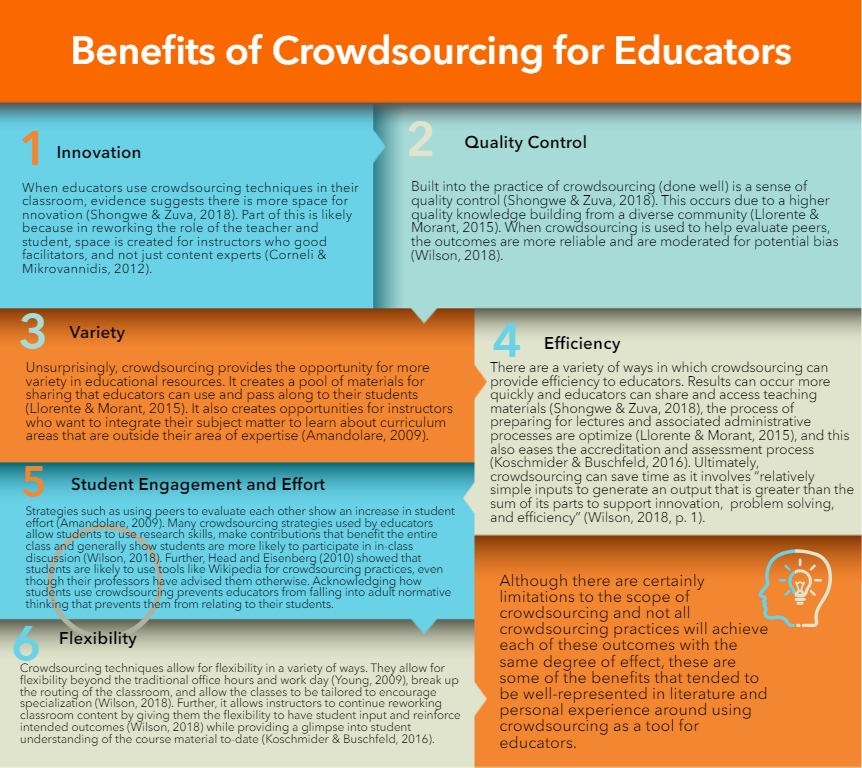

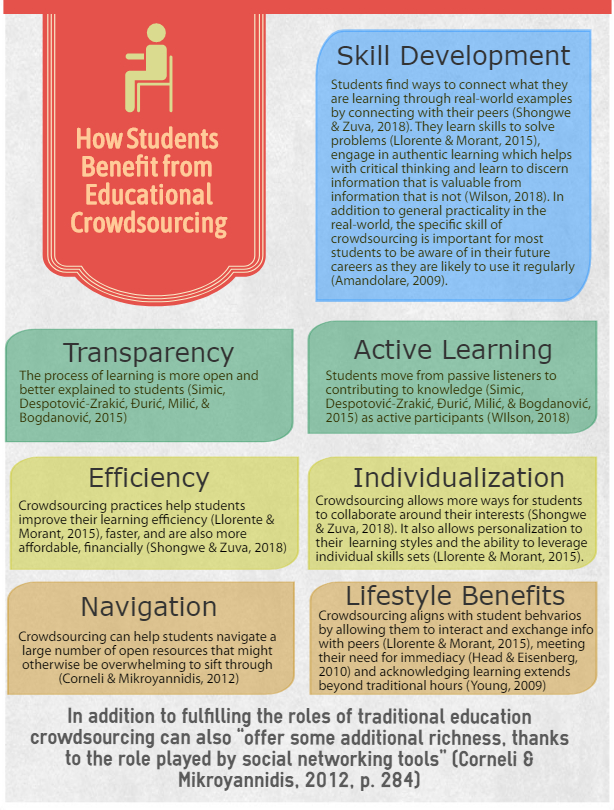

Benefits

The Future of Crowdsourcing

In this section of our chapter we will be revisiting the definition of crowdsourcing from the beginning of our chapter and discussing the accessibility of crowdsourcing, how its easy to apply and reap the benefits of in a kindergarten classroom and a college level course. We will discuss how a student working in crowdsourcing classrooms from a young age through college might be better prepared for today’s work environment. We will also spend some time discussing a few modern technologies that could help facilitate crowdsourcing in the online classroom in the future.

We started our chapter with the definition from the Journal of Information Science (Estellés-Arolas., & González-Ladrón-de-Guevar, 2012) which outlined three main characteristics of crowdsourcing

- The crowd

- The source (the one with the problem to be solved)

- The transaction – crowd receives emotional or social need satisfaction and sourcer receives unique solution to problem.

This model has worked in classrooms for a long time, in the inquiry/discovery models we have already discussed. We know the equation works. Classrooms that use the crowdsourcing model receive unique solutions, increased student satisfaction/ internal motivation, empowerment in district and school policy decisions and an easier workload when the burden of lesson planning is shared collectively.

The future of crowdsourcing in the classroom will most likely continue along these same lines. We based our future predictions on the current uses of crowdsourcing and simply applied the definition to areas of student and teacher interaction that we felt worked well with crowdsourcing. As an educator of going on ten years, I (Rachel) used my classroom knowledge and personal experience as an educator to select situations where there existed the three necessary elements of crowdsourcing we discussed above, but also a fourth element, opportunity to increase learning through access to a diverse, more knowledgeable or unique crowd.

Discovery-based learning has been migrating from the STEM fields into arts and literacy. We will likely see increased adaptations of this model, especially as more classrooms in the K-12 arena come online. In higher education, we will likely see crowdsourcing continue to make great increases, as online classrooms continue to gain in popularity. Collaboration is the name of the game for future job seekers. Networking is a huge element to successful career paths and crowdsourcing teaches many of the skills necessary to be a successful net-worker or to work dynamically in a collaborative, team based work environment.

We believe that the more interesting aspects of the future of crowdsourcing have to do with adaptability or accessibility. The best part of crowdsourcing, is that anyone can be a valuable part of the crowd. The more unique and diverse the crowd is, the more unique and valuable the solution will be. As long as there is a capable facilitator offering the crowd useful, real-world problem scenarios to solve and in a classroom environment, facilitating the development of skills like effective communication, literally any student at any age can engage with this method at a high level.

Pause and Consider

Jump back to the sway presentation here and review the section on future applications of crowdsourcing.

- What excites you about the future of crowdsourcing?

- Do you think it is a trend or a treasure?

- Has reading this chapter changed your opinion on crowdsourcing? If so how?

Age: is it really just a number?

One of the really exciting ways we are predicting crowdsourcing will change in the future of K-12 education relates to mixed ability groups. This prediction is based on the definition of the crowd from from the Journal of Information Science (Estellés-Arolas., & González-Ladrón-de-Guevar, 2012) which highlighted the value of the crowd as a heterogeneous mix Right now the most interaction students receive on a multi-age level are in K-2 mixed ability classrooms or with “buddies” in older classrooms who come to do a project. Honestly, this has never made any sense to me as an educator. Older students need practice leading group discussions, facilitating problem solving and working to build a collaborative, effective team. Sounds a lot like the job of a crowdsourcer, no? Younger students really benefit in a hundred ways from working with older students, watching them engage with materials and conversations can inspire and excite younger learners. Here are a few ways we would love to see crowdsourcing adapted to allow more interaction between multiple age groups of students in a K-12 or even a collegiate environment

Follow the Leader

High school leadership model

- High school students leading STEM field discovery based learning experiences for a mixed age group of elementary students (K-2 and 3-5).

- Elementary and middle school students forming policy discussion groups to shape the way school decisions are made, with high school leaders who then share the findings with the school board

- High school students working with teachers to lesson plan for middle and elementary students and then teaching the lesson they create together.

All of these could be adapted for seniors in college helping freshmen both in their field of study and in the humanities required by most institutions. Leading study groups, tutoring and getting feedback are all areas where seniors, using crowdsourcing could have a huge impact on the ability of freshmen to successfully start their college career.

Apprenticeship model

Apprenticeship is a concept that is used a lot in trade school education, but it could be really valuable in a lot of ways both in K-12 and higher education.

High school or college students rotate through different inquiry based, real world, problem solving scenarios with different professionals (college professor of mathematics, biologist, robotics engineer, physicist, artist, graphic designer, public relations specialist, journalist etc) where they benefit from the professionals knowledge of the subject material and can engage with them in the problem solving in a more authentic way then in a contrived example from a text book led by a teacher. Mixing professionals into the crowd can model for students who the people actually working in the field engage with text, research, materials, etc.

This strategy would be most effective for skill based learning, but could also help foster networking skills and increase student motivation,

Student Voices Matter Most

In our research, the most exciting application of crowdsourcing was the way it has been used my educators to influence district and public policy in education. If it was empowering for teachers, imagine how empowering it would be for students. In education, the survey is the most popular way to currently get student feedback and allow students to have a voice in their education. Surveys, at heart though, are still secondary, responsive to decisions. The survey data may be taken into account when making decisions, but the power is still not in the hands of the people who are being impacted the most by those decisions. If crowdsourcing has been so effective for teachers to make necessary changes in policy, it stands to reason that students could benefit as well. We would also like to see this use of crowdsourcing continued on and expanded for teachers as well.

Public Policy and Decision Making:

Student led focus groups

In high schools we often see schools offer leadership positions like student council president, treasurer, etc to the student body. Largely these positions have little to no actual power or influence and worse, provide no real life scenarios for students to practice and grow their leadership skills. Crowdsourcing could really change that.

- Students could join focus groups led by school board members (treasury, policy, community relations, etc) and the school board official in charge would put to the committee members and students in the focus group the issues that are really affecting the school. The team then would use crowdsourcing principles to solve the problems. Because of that wonderful accessible nature of crowdsourcing, students even in the late elementary age group could be considered for the focus groups.

- Because there are so many areas of policy and decision-making that affect education, many more students could be involved, and gain the benefits of real world leadership modeling and practice.

- This would also help make decisions that are more unique and directly related to the audience they most affect, which would increase the likelihood that the decisions would effectively solve the problems facing the community.

This model could be applied upwards to the district level for educators and could be expanded to involve community members as well.

New Gear for New Goals

In today’s tech-ed out world, the right gear can really make or break a project. We have a plethora of technology available in today’s classroom, but are we using it effectively and, since we have it so readily available, can we use it for crowdsourcing efforts to provide better opportunities for students, families and teachers to communicate?

Upcycled: teaching old tech new tricks

Online Learning Management Systems (LMS) are currently extremely popular, even necessary parts of higher education. Since they are so ubiquitous and accessible to students and faculty, here are a few ways we think they might be re imagined to also aid crowdsourcing efforts on college campuses

- Peer to peer crowdsourcing: IT concerns, health questions, financial aid, general campus knowledge, basic information about the surrounding locations – all of these could be answered communally. The poster with a question would be the sourcer, and the knowledgeable and diverse crowd would be the student body at large. A “tab” or “group” section for this kind of crowdsourcing under the appropriate section of the portal (IT, Health, Student Relations) or even a link to a local, private Facebook group could serve this purpose.

- Course related sourcing: What if students currently taking a course could connect with students who previously took the course or who are currently graduates who are working in that field of study covered by the material of the course? Instead of asking your professor the same questions over and over, ask a student or professional further advanced in the field. More interesting, and again, the students are building a network useful for later in their careers. The professor would need to moderate student to student contact to ensure no passing on of the exams occurs but it would be very easy to build this kind of discussion forum into the existing online portals used to support online learning like Canvas at Ohio State for example, or Blackboard or Carmen.

This applications could be scaled for high school students as well. it would be very interesting to create a high school or college portal where some graduates of the high school, now in colleges around the country, help high schoolers answer questions about college in an online format.

The laptop cart

Ah, the laptop cart. The most ignored, dusty piece of technology in the school. It hides in the library closet usually and is either so fought over that its never available, or never used except by that one teacher. Laptops for students have become a huge source of grant writing efforts and many schools have this technology. Can we reimagine it to include crowdsourcing support?

- Many of the efforts we have discussed for K-12 crowdsourcing could be brought online and facilitated through the laptops. Instead of marching high school students down to the elementary classrooms, they can work in focus groups, teams, etc on the laptops via platforms like Skype or Facetime. High school students can teach lessons (recorded or live) to elementary students which would give them practice learning online, so to speak, and give high schooler’s practice working with materials in new ways.

- Parent teacher conferences and feedback can absolutely be brought online. Apps or Ipads and laptops can be extremely useful tools for communication that could alleviate the burden on parents to come to the school so often. Teachers can push problems out to the parent community like:

- We are seeing a lot of absences lately, how can we encourage students to continue to attend school through the end of the year?

- Testing is coming up how can we support students during the long days of testing?

- Parents can provide feedback after teacher conferences via online apps or groups, connected to school administrators. They could also provide feedback for new school policies and decisions this way.

It’s exciting to think about ways crowdsourcing can be used in the future. While we certainly weren’t able to predict every new application, the above examples highlight the features we think makes crowdsourcing such a wonderful methodology for education: its accessibility, the ability to conduct the entire process online, the skills for future careers that it allows students to learn and the mutually beneficial transaction between the crowd and the sourcer. We hope you now feel as excited about the present and future of crowdsourcing as we do.

References

Amandolare, S. (2009, August 18). Is crowdsourcing the future of college education? Retrieved from http://www.findingdulcinea.com/news/education/2009/august/Is Crowdsourcing-the-Future-of-College-Education–.html

Corneli, J., & Mikroyannidis, A. (2012). Crowdsourcing education on the web: A role based analysis of online learning communities. In A. Okada, T. Connolly, & P. J. Scott (Eds.), Collaborative learning 2.0: Open educational resources (pp. 272-286). Hershey, PA: IGI

Dunlap, J. C., & Lowenthal, P. R. (2018). Online educators’ recommendations for teaching online: Crowdsourcing in action. Open Praxis, 10(1), 79-89.

Estellés-Arolas, E., & González-Ladrón-de-Guevara, F. (2012). Towards an integrated crowdsourcing definition. Journal of Information Science, 38(2), 189–200.

Gee, R. (2013, August 12). Crowdsourcing ideas for a better school. All Tech Considered. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2013/08/12/211369819/crowdsourcing-ideas-for-a-better-school?t=1552848213759

Head, A., & Eisenberg, M. (2010). How today’s college students use Wikipedia for course related research. First Monday 15(2), 1-15.

Junco, R. (2014). Engaging students through social media: Evidence based practices for use in student affairs. San Francisco, CA: Wiley/Jossey-Bass.

Koschmider, A., & Buschfeld, D. (2016). Shifting the process of exam preparation towards active learning: A crowdsourcing based approach. GI-Jahrestagung.

Llorente R., Morant M. (2015). Crowdsourcing in higher education. In F. Garrigos Simon, I. Gil Pechuán, S. Estelles-Miguel (Eds.) Advances in crowdsourcing (87-95). Switzerland: Springer.

Loewus, L. H. (2013, July 2). Crowdsourcing: The teacher-voice solution. Education Week Teacher. Retrieved from https://blogs.edweek.org/teachers/teaching_now/2013/07/crowdsourcing_the_teacher-voice_solution.html

Online Universities (2010, July 10). 10 awesome examples of crowdsourcing in the college classroom. [web log comment]. Retrieved from https://www.onlineuniversities.com/blog/2010/07/10-awesome-examples-of-crowdsourcing-in-the-college-classroom/

Peachey, N. (2017, August 29). Digital skills that teachers need for the classroom #3: The ability to crowdsource information. Retrieved from http://www.cambridge.org/elt/blog/2017/08/29/digital-skills-that-teachers-need-3-crowdsourcing-information/

Shongwe, T., & Zuva, T. (2018). Benefits of crowdsourcing and its growth in the education sector. 2018 International Conference on Advances in Big Data, Computing and Data Communication Systems (icABCD), 1-6.

Simic, K., Despotović-Zrakić, M., Đurić, I., Milić, A., & Bogdanović, N. (2015). A model of smart environment for e-learning based on crowdsourcing. Journal of Universal Excellence 4(1), 1-10.

TED. (2016, April 22). Chris Sigaloff: Crowdsourcing education creating room for the usual suspects [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lOZdxvnQJ3g

Walker, R. (2019, April 1). Email.

Wilson, M. C. (2018). Crowdsourcing and self-instruction: Turning the production of teaching materials into a learning objective. Journal of Political Science Education, 14(3), 400-408.

Young, J. R. (2009, November 1). Colleges try ‘crowdsourcing’ help desks to save money. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/