4 Chapter 4 – Leveraging technology to create more inclusive classroom experiences for international students

Carey, A., Miller, M., & Tuttle, R.

Abstract

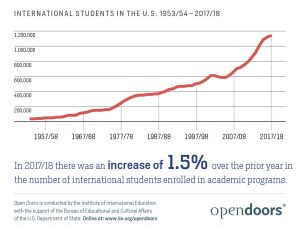

This chapter strives to answer the question, “How can educators leverage technology to create inclusive classroom experiences for international students?” In order to answer this question, common challenges faced by international students are identified and explained. This is important because the number of international students at U.S. institutions have nearly doubled since 2000, and international students make up 5.5 percent of students enrolled in U.S. higher education institutions (Institute for International Education, 2018). Specific focus was placed on the experience of international students in classroom settings. In addition, inclusive classroom environments are explained in order to establish a shared understanding of what it means to create an inclusive classroom and why it is important for supporting international students’ academic experiences. Using a pedagogical framework established by Lin and Scherz (2014), we introduce four topics, focusing on different educational technologies or practices that have the potential to contribute to an inclusive classroom experience for international students. These technologies or practices include introducing Minecraft into classrooms, incorporating ePortfolios into curriculum, and engaging in virtual exchanges. It is our hope that these technologies or practices provide inclusive classroom experiences which in turn create a supportive academic environment for international students at U.S. institutions.

The Academic Experience of International Students

International student presence in U.S. higher education institutions has increased rapidly since the turn of the century. According to the Institute for International Education’s 2018 Open Doors report, while there were just 547,867 international students on American campuses in the year 2000, by 2018, that number had nearly doubled, reaching 1,094,792 students. International students come for undergraduate and graduate programs as well as for non-degree coursework. In fact, in 2017-18 alone, 271,738 new international students entered American institutions (Institute for International Education, 2018). In total, international students currently make up 5.5 percent of enrollment in U.S. higher education institutions (Institute for International Education, 2018). Beyond these students who have directly enrolled in U.S. institutions, more overseas students are engaging with students in U.S. classrooms as part of their coursework, thanks to technology that enables communication between students in physically distant locations, through programs referred to as virtual exchange. Given this large volume of international students with physical and virtual connections to U.S. campuses, an understanding of how international students experience U.S. classrooms and how they adjust is warranted.

International students on U.S. campuses face many challenges. In addition to the numerous stressors experienced by most American college students, such as learning to acclimate to new academic and social environments and to live independently, international students face additional stressors, including language difficulties, financial problems, homesickness, new academic norms and conventions, and difficulty in making friends with domestic students (Le, LaCost, & Wismer, 2016; Poyrazli, Arbona, McPherson, & Pisecco, 2002). While these challenges are encountered both inside and outside of the classroom, this chapter focuses on the international student experience in the classroom, and therefore, challenges in the academic environment will be the focus of our attention.

Challenges international students face in the classroom can be described in three main categories: linguistic, cultural, and academic. First, many international students face linguistic challenges, particularly in the areas of speaking and listening comprehension which impact their participation in the academic experience (Mesidor & Sly, 2016). These linguistic challenges affect their ability to comprehend lectures and participate in class discussions as well as add significant extra time required for reading and writing assignments (Lin & Scherz, 2014). Second, one major cultural challenge is learning to develop and navigate social relationships, with faculty, with advisors, with other international students, with domestic students, and with members of the community. Lin and Scherz’s (2014) study found that most participants regretted the limited opportunities to engage with American students both inside and outside the classroom. Other cultural differences also impacted their experience, such as different expectations of time. Finally, in the area of academic challenges, international students may come to the classroom with expectations based on their home cultures, and struggle when the class itself or the interaction with professors or peers is not what they anticipated. Differences in educational styles may also be a major challenge. For example, some students may have more familiarity with authoritative teaching styles while American professors may expect more dialogue and interaction among classmates. Different evaluation methods, such as essays or papers versus multiple choice exams, may also surprise some students and cause anxiety (Mesidor & Sly, 2016).

Given the challenges international students face adjusting both socially and academically in a new educational environment, an examination of pedagogical strategies that may foster more inclusive classroom experiences and academic success for international students is of paramount importance. Lin and Scherz (2014) conducted a study with non-native English speaking international students and developed recommendations and a framework for supporting students’ linguistic, cultural, and academic needs. Their recommendations include employing the following practices:

Finally, it is important to note that international students often have high expectations of themselves, which may be perceived by some as unrealistic given all of the adjustment issues they are faced with in coming to a new country and academic system. However, Mesidor and Sly (2016) found that international students’ belief that they can succeed, in other words, their self-efficacy, plays an important role in both their academic success and their confidence in interacting with others. Employing one or more of the pedagogical approaches suggested by Lin and Scherz (2014)—learner-centered instruction, culturally responsive teaching, and/or scaffolding—may serve to increase students’ self-efficacy and subsequently their success.

Creating Inclusive Classroom Environments for International Students

Inclusive classroom environments support the academic experience of international students. Inclusive classroom practices create understanding and awareness of social education issues that may impact students’ learning (Florian & Rouse, 2009). While inclusive classroom practices construct a more positive learning environment for all students, international students can especially benefit from inclusive educational practices because they often face additional obstacles centered on linguistic, cultural, and academic challenges. Students’ sense of belonging is at the core of creating inclusive classroom experiences. While all students can face transitional and academic challenges, students of minoritized or less privileged backgrounds can encounter more difficult challenges as they face what they distinguish to be unwelcoming or hostile environments (Carter, Locks, Winkle-Wagner, & Pineda, 2006; Kalsner & Pistole, 2003; Locks, Hurtado, Bowman, & Oseguera, 2008). As educators, it is our responsibility to be aware of challenges facing minoritized populations in the classroom. In addition, it is important to create educational experiences that support inclusive experiences for all students. In the next section, we will share four educational technologies or practices that can contribute to a more inclusive classroom experience for international students.

Potential Learning Opportunities Present in the Gaming Environment Minecraft for International Students.

In this section, we will be exploring the potential learning opportunities present in the gaming environment of Minecraft specifically for providing enhanced inclusiveness for international students that are enrolled and participating in classrooms. Hopefully, by allowing and playing with the virtual blocks of Minecraft, this will spark new development of better understandings, comprehension, communication, collaboration, problem-solving, and an enhanced learning environment for not only international students but all students. We hope this section will provide future direction for educator improvement where the focus is placed on enhancing both utilization of digital technology and teaching skills in the classroom.

The independent research and analysis conducted on the Minecraft section centered upon several major areas. First, the Karsenti, Burgmann, and Gros (2017) exploratory study on “Transforming Education with Minecraft” and the Lane and Yi (2017) reference of the chapter in the book called Cognitive Development in Digital Contexts were researched and analyzed. Second, the Edutopia (2013) video “Using Minecraft as an Educational Tool,” Microsoft (2017) video “Play and Learn with Minecraft Education Edition,” Minecraft (2016) video “One Educator’s Journey with Minecraft: Education Edition, ” and Bureau of Education and Research (2011) video “Practical Classroom Strategies for Making Inclusion More Successful, Grades 6-12,” were also used for research and analysis for this section. Finally, this researcher’s professional experience and training creating, establishing, and maintaining an inclusive work environment and mentoring individuals were also considered for this research and analysis. Because of the limited time frame and scope of this project no extensive statistical analysis or interviewing was conducted. The culminating of all the research materials mentioned above were critically studied and analyzed. From this critical analysis, independent thoughts, ideas, conclusions, and recommendations were developed to correspond to the theme of this section since no direct research concerning this topic was found or is available. The ideas and claims presented in this Minecraft section are again based upon the independent research and analysis and try to follow a logical or common-sense approach based upon the researcher’s independent thought process and background. However, any overlapping of ideas, concepts, or conclusions with any other study conducted is unintentional and purely coincidental. Please view all ideas, concepts, examples, recommendations, and/or conclusions based solely from the researcher’s perspective from the above mentioned research and analysis and to act as evidence to support the claims expressed in the Minecraft section.

What is Minecraft and What Might be its Relevance to Learning

Minecraft is an extremely popular multi-awarding winning game for kids and adults. The Minecraft Education Edition is designed specifically for classroom use and gives educators the tools they need to use Minecraft in their lessons. On the surface, Minecraft appears to be only a game about placing and breaking blocks to build stuff. However, Minecraft, when used in the classroom, can be utilized to enhance learning by showing relevance to the subject matter covered in a unit and assist in student creativity. Minecraft is designed to be collaborative, with the outcome of the engagement of students, development and sharing of student skills, and opportunities for learning teamwork and collaboration for all students. Even though this section may focus on K-12 students, students and teachers in higher education setting can utilize, develop, and experience the same outcomes if the content of the material is directly relevant to the information or content covered in the class. In addition, international students could possibly have tremendous gains because of the collaborative nature of the use of Minecraft through the exposure, and the teams developed and utilized in the learning process.

The Edutopia (2013) video “Using Minecraft as an Educational Tool,” below looks at the Minecraft game-like learning principles used in real classrooms. The video shows how students enjoy the use of Minecraft in the classroom as well as the student’s engagement. The video offers tips and tools for bringing Minecraft into your own practice into the classroom and directly shows teachers and students working in the classroom. Another concept that is relevant to this chapter is the mentioning of digital citizenship, that is discussed later on. Finally, the video displays real classroom environments where students are displaying collaboration, teamwork, and sharing of their skills with other students. This brings about inclusion, and all students feel included and that their ideas are important.

The Microsoft (2017) video “Play and Learn with Minecraft Education Edition,” below shows students creating a museum of me using Minecraft. The video shows several students enthusiasm and expressing creative and interesting things about themselves using Minecraft. All the students in the video showed involvement in the activities where the students were able to play and learn at the same time. Not only were the students able to develop problem-solving skills but numerous areas of the video showed students communicating with one another and sharing interesting things about themselves. By showing the development of communicating and sharing ideas with one another fully in the Minecraft activities, this is fostering a positive learning environment where all students feel included no matter what their background or country of origin.

Minecraft can also be used effectively as a pedagogical tool to motivate all students. It can be used to motivate different genders as well as students from different countries of origin. Since most students love to play and work in the digital environment of Minecraft as shown in the videos above, it does seem that motivation should be easier than most curricular based activities. In addition, scaffolding, which is the different instructional techniques used to assist students in better understanding and learning in the classroom, can be utilized to enhance learning using the digital environment Minecraft.

A couple of elements need to be present for scaffolding to be successful using the pedagogical tool Minecraft. First, there needs to be an academic purpose or objective or point to the use of this digital environment. This purpose or objective needs to be observable and measurable to determine its relevance. Next, the students need to show engagement. Since we have seen from the previous videos that students are excited and enjoy using Minecraft, they also are given the opportunity to build skills such as problem-solving, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration. By students working in this Minecraft digital environment and using this pedagogical tool, the classroom naturally becomes inclusive. The students work together for a common goal and are all equally important and a vital part of whatever team the teacher or instructor assigns them too. International students can truly reap the benefits and can utilize it for not only better understanding the learning and classroom environment and subject matter but also to learn about other non-international students and vice versa. The Mudpit (2014) video “The Minecraft Pedagogy Pupilarium,” below used Minecraft as a teaching environment to discuss effective pedagogy. This video can give the teacher or instructor/professor a guided outline and steps on how to build an enhanced learning environment.

Possible Ideas on How and Why to use Minecraft and What Skills might be Developed

There are many ways to integrate Minecraft into the classroom. Since students, no matter what the level, view games more as fun and entertaining, Minecraft can be utilized as a tool to engage students in curriculum through the game. Even though, most of the examples that will be provided are focusing on the K-12 educational levels, the transition and usability at the higher educational level could be developed either through enhancements, custom modifications, or addition of more rigorous activities or educational objectives. Below are some ways Minecraft could possibly assist students:

Some examples of possible uses of Minecraft in the classroom:

The Minecraft (2016) video “One Educator’s Journey with Minecraft: Education Edition,” below follows the journey of Katja Borregaard, an educator at Skt Josefs Skole in Roskilde, Denmark. This is Katja’s first experience using Minecraft Education Edition in the classroom. During her integration she not only learns about the technology but also learns from the students. Just like the other videos shown in this section where students show true excitement and enthusiasm for using this digital environment in the classroom. Students are also shown working and learning together in what appears to be a very inclusive and positive learning environment. In numerous areas of video, students are shown communicating and sharing with one another. One of the greatest ideas that is shown in the video is that the student and teacher roles are in some cases reversed where the students are teaching the teacher. This is truly showing that students are a vital part and included in learning classroom environment utilizing the Minecraft digital environment. Some of the skills that are talked about in the video are similar to the ones discussed in this chapter; communication, collaboration, and problem-solving/critical thinking. Finally, since the classroom in this video is in Denmark, the idea of international student involvement could be thought of in reverse if a U.S. student entered this learning environment. Overall, the classroom environment appears to be inclusive and all students would appear to be included and important.

The Bureau of Education and Research (2011) video “Practical Classroom Strategies for Making Inclusion More Successful, Grades 6-12,” below is an overview video for teachers to be able to more successfully address the wide range of students in their inclusive classrooms. The video states that there are techniques and practices for creating productive, highly effective inclusive learning environments at the secondary level. The main idea that is talked about in the video, which is discussed in detail in this section, is that students should be accepted and included in the classroom and learning environment. These concepts are supported in the video and this section and the entire chapter. At the heart of both the video and this chapter, students have the right to be in the classroom therefore they should be included and important, no matter where they come from, their level of physical or mental abilities, and their educational level. Finally, the video emphasizes that a wide variety of techniques and approached are needed to build an inclusive classroom while maintain the appropriate level of curricular expectations.

Possible skills that might be developed or enhanced for International Students by using Minecraft

- Better Engagement with other students by using the Team or Group based approached.

- Building better communication skills by sharing with other students their background and international student perspective.

- Building better interactions and collaborating with other students.

- Developing better problem-solving skills.

- Building better Digital Citizenship skills.

- Developing a sense of purpose, responsibility, and inclusiveness while building a sense of self-worth and importance in the Team or Group based Minecraft activities.

Utilizing ePortfolios to Create More Inclusive Classroom Experiences for International Students

Introduction of ePortfolios

Electronic portfolios (ePortfolios) have become a prevalent curricular tool within the higher education setting. Generally, ePortfolios are defined as “a digitized collection of artifacts including demonstrations, resources, and accomplishments that represent an individual, group, or institution” (Lorenzo & Ittelson, 2005, p. 1). ePortfolios are a compilation of graphics, texts, and multimedia components stored on a website or other electronic device, like a CD-ROM or DVD (Lorezno & Ittelson, 2005). The concept of ePortfolios emerged from traditional paper-based portfolios used demonstrate and collect works as they pertained to certain disciplines, such as art, teaching, and finance (Challis, 2005). Although ePortfolios can fulfill the need of archiving content, information, experiences, and achievements, they are most impactful when used a reflective tool (Reese & Levy, 2009).

This video, titled”What is an ePortfolio?” is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xvqBORISA5k, is from Auburn Unviersity, and provides a brief explanation of the ePortfolio tool.

ePortfolios contribute to an inclusive educational experience. ePortfolios encourage students to take ownership over subject-matter competence. When used effectively, ePortfolios allow students to present information, knowledge, and experiences in an authentic way that support the context of their experiences (Parkes, Dredger, & Hicks, 2013). Using artifacts and reflections, ePortfolios allow students to uniquely connect their academic content and experiences, with their personal and professional interests and involvements.

When used thoughtfully, ePortfolios are effective educational tools. Reese and Levy (2009) identified three educational outcomes from ePortfolio use in the classroom: contribute to “authentic learning experiences” (Reese & Levy, 2009, p. 3), answer to an educational era of transparency, and connect educators to students that feel comfortable communicating with multiple modes of media.

Use of ePortfolios as a Learner-Centered Instruction for International Students

Learner-centered instruction can create an inclusive educational environment for international students. Learner-centered instruction approach is designed to develop deeper understanding in an inclusive environment for international students (Lin & Scherz, 2014). This pedagogical approach allows instructors to create an inclusive educational framework while they instruct on content, resources, and processes, as it requires that students develop their own goals for learning and actively participate in the learning process (Lin & Scherz, 2014). The educational style is effective as it places responsibility and ownership on the student to engage in the learning process.

Learner-centered instruction supports deeper understanding as students:

- Establish goals around their learning

- Analysis and synthesize information

- Work collaborating with other students

- Develop questions from the readings and content

- Work alongside instructors to create learning opportunities in class

(Lin & Scherz, 2014)

Learner-centered instruction is an impactful pedagogy for international students. Learner-centered designed allows international students to ownership of their educational experience and provide influence in how students and instructors engage in academic content. Creating an environment where students’ experiences and ideas are valued and encouraged provide a positive environment that is linguistically, culturally, and academically supportive (Lin & Scherz, 2014). This pedagogy celebrates international students unique experiences and perspectives, pushes student to engage with their instructors and peers, and encourages analysis and reflection of content and experiences. ePortfolios can support international students in their linguistic development as it can encourage discussions with their peers around content shared in their ePortfolios. This type of deep learning can assist international student in not only strengthening their academic ability, but also their confidence in engaging in the classroom and with their peers.

ePortfolios can support learner-centered instruction for international students. The reflective aspect of ePortfolios allow for internationals students to connect the content they are learning through the classroom with the experiences they are navigating in their academic and personal lives. ePortfolios can provide international students with the space to connect with academic content in a way that is engaging to them personally. According to Parkes, Dredger, and Hicks (2013), students reached deeper levels of critical thinking through the multi-modal methods afforded by ePortfolios. In addition, ePortfolios allow international students to share their ideas in an authentic way that celebrates their experiences and perspectives.

Inclusion of ePortfolios in Curriculum for International Students

Thoughtfully including ePortfolios into curriculum can create an inclusive educational environment for international students. In order to successfully integrate ePortfolios into an educational environment, the curriculum must purposely incorporate ePortfolios and students must connect the experience with their holistic development (Challis, 2005). When including ePortfolios into a curriculum, the following must be considered: training for the instructors and students, purposeful assignments that incorporate ePortfolio use, and frequent and thoughtful feedback.

Appropriate training for both instructors and students allows for users to confidently and fully utilize ePortfolios in their educational experience. Instructors should receive training to help them understand the basic abilities of the tool as well as to be able to troubleshoot common issues students encounter when developing their ePortfolio. As for students, training and practice using the ePortfolio should be included in their educational experience. Practice engaging with the tool should occur in and out of the classroom. This practice should include regular engagement with the instructor and other peers to assist in developing foundational knowledge in working with the tool. Lastly, students should have access to additional resources and help guides to assist them in problem solving when they do encounter issues when completing assignments.

Purposeful assignments is essential for successfully incorporating ePortfolios into curriculum. Deliberative choices within teaching must be made when including ePortfolios (Parkes, Dredger, & Hicks, 2013). Assignments that incorporate the learner-centered instruction provide potentially strong educational benefits when integrating ePortfolios. Experiences that include group work, are exploratory in nature, or include design processes can push international students to have interactive and deep educational experiences with their peers. Furthermore, by connecting ePortfolio use with these learner-centered experiences, students have the opportunity to document their learning and experiences through methods and modes that uniquely represent their personality and highlight their personal and professional interests. Additionally, the reflective nature of ePortfolio creates a more inclusive experience as it allows international students the opportunity to share their story and experiences that impact the manner in which they engage with the world.

Frequent and thoughtful reflection is essential for successfully incorporating ePortfolio use into curricular experiences. The use of ePortfolios may be a new experience for many students. Feedback on how they using the tool, engaging with the content, and the depth of their reflection will allow students to more confidently utilize the tool for future curricular assignments. In addition, frequent and thoughtful feedback on their reflections can provide encouragement to international students as ePortfolio use may the students to engage in academic content in ways different from their previous educational experiences.

The Role of Virtual Exchange in Creating More Culturally Inclusive Classrooms in Higher Education Institutions

Introduction to Virtual Exchange

Virtual exchanges have been growing in popularity in recent years. The idea behind such exchanges is that they allow students from different cultures in distant locations across the globe to connect virtually and engage in sustained conversation and collaboration. Imagine, for example, students in a Japanese language classroom in Ohio connecting with students in Japan to work on a project together comparing Japanese and American culture. Virtual exchanges, otherwise known as online intercultural exchanges, typically incorporate such collaborative tasks, some kind of collective inquiry, as well as ample opportunities for social interaction (O’Dowd & Lewis, 2016).

This video, titled “What is Virtual Exchange?,” available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ukKXruXq7js, is from the Erasmus+ Virtual Exchange project in Europe, and features students who have participated in online intercultural exchanges explaining the concept in their own words.

This video, titled “Introduction to Virtual Exchange,” available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uzctYHu69zE, was developed by the Qatar Foundation International and provides an overview of the framework for virtual exchanges.

Numerous terms exist for these types of collaboration. In addition to virtual exchange, other terms such as online intercultural exchanges (or OIE), collaborative online international learning (or COIL), and telecollaboration are often used interchangeably. The word cloud below depicts the various synonyms for virtual exchange.

Rationale and Challenges for Virtual Exchange

While the field of virtual exchange has grown rapidly over the last twenty years and many research studies have been conducted and published, the studies to date have tended to focus on a single project. These smaller-scale studies demonstrated enthusiasm on the part of instructors and students as well as some positive gains in learning outcomes, such as language development, intercultural communicative competence, and online literacies, to name a few (Helm, 2015). However, there remains a need to conduct more large-scale surveys to identify the current state of the field.

The rationale laid out in the literature for incorporating virtual exchanges into American higher education is three-fold. First, virtual exchange is said to help both domestic and international students build skills for their future careers. Those skills include both foreign language and intercultural communication skills as well as technical skills, referred to as e-literacies or e-skills (O’Dowd & Lewis, 2016). Second, virtual exchange can be used to bolster institutional internationalization, a priority for many higher education institutions in the 21st century. Third, virtual exchange can be said to contribute to a social justice agenda by allowing students who may not be able to physically travel internationally to have an international experience.

Of course, inherent challenges exist with online intercultural exchanges. For example, differences in the availability and types of technology that can be accessed in classrooms across the globe is one challenge (O’Dowd, 2018). Faculty may also lack sufficient pedagogical training to incorporate such practices or technology into their teaching. Locating partner classes in overseas institutions, where curriculum or academic calendars or time zones may not align, is another obstacle.

In addition, the unpredictable nature of international collaboration and discussion means that the content and direction of the course may not be fully controllable which could be uncomfortable for some instructors (O’Dowd & Lewis, 2016). Helm (2015) found in her survey of 210 university language teachers and 131 students in 23 different European countries that time is the greatest barrier for individual teachers to incorporate virtual exchanges into their classrooms. Yet, the instructors surveyed seemed to be “reinventing the wheel” in designing new exchange projects from scratch. She found a need for more “pre-packaged telecollaboration projects with a more or less fixed curriculum, duration, assessment tools, and even facilitators for specific target groups and contexts” (p. 212).

One way to consider best practices in the field of virtual exchange is to examine the reasons why many projects fail. Failed communication is the most common reason and can occur on four different levels: individual, classroom, socio-institutional, and interactional levels (O’Dowd & Ritter, 2006). The below chart explains common reasons for failure at each level, according to O’Dowd and Ritter (2006). Examining these reasons for failure can help instructors avoid pitfalls and design a virtual exchange project that is more likely to succeed.

History of Virtual Exchange

While the roots of intercultural exchanges themselves, in the form of pen pals, for example, can be traced back hundreds of years, virtual exchanges got their start with the advent of the internet in the early 1990s. These early forms of online intercultural exchange were limited to synchronous text-based communication, such as chats, and are sometimes described in the literature as “slow motion conversations” (O’Dowd & Lewis, 2016, p. 8). As technology evolved, websites were created to link physically-distant classrooms and allow for collaboration. These collaborative projects were referred to as intercultural email classroom connections (IECC), or e-Tandem, which allowed individuals in different countries to form partnerships and practice their foreign language skills with each other. Virtual exchange was born in computer-assisted language learning, under the terminology of “telecollaboration” or “online intercultural exchange,” and was used as a way to help students develop their foreign language and intercultural communicative competence. Examples include the Cultura and Teletandem projects.

Since then, virtual exchange has expanded rapidly to other disciplines and fields. As O’Dowd (2018) describes, subject-specific virtual exchanges now frequently occur in business studies initiatives, using the terminology “global virtual teams,” where practitioners lead students through projects, such as X-Culture, designed to give students the intercultural skills necessary for the workplace. Service providers, such as Soliya and Sharing Perspectives, have also come on to the scene to offer facilitator-led approaches to virtual exchange with the goal of helping students to develop cross-cultural communication skills, critical thinking skills, and digital literacies. Finally, O’Dowd (2018) describes the “shared syllabus approach” in which courses in different universities are taught from a shared syllabus with the goal of developing international perspectives, intercultural competence, and digital skills of students. An example of this approach is the State University of New York’s COIL Institute for Globally Networked Learning in the Humanities.

Expansion is also happening on the local level. While virtual exchanges began as classroom-independent exchanges, more instructors are now using these types of exchanges in an integrated way in their classroom, and more institutions are integrating such exchanges at the institution level. The below depicts examples of online intercultural exchanges at each level of integration.

Exemplary Virtual Exchange Providers and Projects

As the field of virtual exchange grows, international collaborative networks have been developed and expanded. Governmental agencies and nonprofit organizations have also begun to increase their investment in these initiatives, sighting the importance of international understanding and the ability of virtual exchange to bring these cross-cultural conversations to students who may not otherwise ever have a chance to interact internationally.

In the United States, the Stevens Initiative at the Aspen Institute is a public-private partnership aimed at connecting young people in the United States with those in the Middle East and North Africa. Established as a tribute to Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens, the initiative receives support from the family of the late Ambassador, the U.S. Department of State, the Bezos Family Foundation, and the governments of the United Arab Emirates and Morocco. They engage in connecting students from U.S. high schools and colleges, such as Johns Hopkins University, Ball State University, and Wofford College, just to name a few, with students across the Middle East and North Africa.

This video, “Stevens Initiative: Virtual Exchange,” available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dGucBMnxH5A, provides an overview of their projects and goals.

This video, “The Stevens Initiative: International Virtual Exchange,” available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ehyOWMgV7e4, is produced by the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs and features a few of the outstanding international projects supported through this initiative.

Another U.S.-based initiative is led by Soliya, a nonprofit organization headquartered in New York. According to their website, they operate “at the intersection of technology, peacebuilding, and global education to foster local awareness and global perspectives” (Soliya, n.d.). They developed the “Connect Program” to bring groups of college students from across the globe together through small-group facilitated discussions on social topics. They also offer facilitation training for those who would like to serve as discussion facilitators.

This video, “Exchange 2.0: Lucas Welch at TEDxTeachersCollege,” available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h8gHXAEwE8k, is a talk by Soliya founder Lucas Welch on the work of Soliya in developing worldwide virtual exchange programs.

Beyond the United States, the Erasmus+ Virtual Exchange network, supported by the European Commission, is perhaps one of the most active networks globally. Instructors in Europe and the Southern Mediterranean can reach out to the network through their online hub to request assistance in setting up a virtual exchange. In addition to supporting online facilitated dialogues, the network supports training to develop virtual exchange projects, advocacy training, and interactive open online courses.

Learning from the Literature on Inclusion and International Students

As virtual exchange involves students from diverse countries, all participating students, even those from the United States, could be considered international students to at least some of their virtual exchange partners. Keeping this in mind, instructors on both sides of a two-way exchange, or facilitators leading exchanges involving multiple sites, could benefit from examining the literature on inclusion and international students. In particular, the concept of culturally responsive teaching, as described by Lin and Scherz (2014), could provide an interesting perspective.

The key characteristics of culturally responsive teaching involve considering the cultural backgrounds of students, valuing and respecting diversity, and facilitating across difference. Therefore, culturally responsive instructors get to know the culture of their students and consider it in all aspects of instruction, from curriculum design to pedagogy to assessment (Lin & Scherz, 2014). Using culturally responsive teaching as a lens through which to ensure that all virtual exchange participants feel valued and included could be a valuable practice for virtual exchange leaders to employ. To do so, instructors and facilitators may need training and/or support which will require an investment from the institution or provider. However, as Lin and Scherz (2014) state, culturally responsive teaching “will not only broaden the scope of domestic students to include a global perspective, it will also help international students better understand the differences and similarities between their cultural and linguistic backgrounds and those of other students and instructors with whom they interact” (p. 30).

Looking to the Future

As O’Dowd writes in the concluding chapter of Online Intercultural Exchange: Policy, Pedagogy, Practice (Lewis & O’Dowd, 2016), the challenge for the future is to find ways to ensure that virtual exchange is used for deep, meaningful, cross-cultural dialogue. Instructors should use the opportunity to underscore social justice and intercultural citizenship ideals in education while operating from a culturally responsive teaching approach. More fields beyond foreign language should also consider implementing virtual exchange activities. Using the medium to discuss more current political, economic, and social issues with diverse students could lead to greater global understanding and cooperation in the future.

Conclusion

Thoughtful integration of technology can create an inclusive classroom environment for international students. Making up nearly 5 percent of the enrollment in U.S. higher education institutions, (Institute for International Education, 2018), international students have a significant presence and impact on the U.S. educational setting.

Keeping in mind the linguistic, cultural, and academic challenges of international students in U.S. classrooms and incorporating Lin and Scherz’s (2013) pedagogical approaches of culturally responsive teaching, learner-centered instruction, and scaffolding, we identified four technologies or practices that can be used to create a more inclusive classroom environment for international students. First, by utilizing the pedagogical approach of scaffolding in a hands-on activity to build upon students’ understanding, we demonstrated that Minecraft could be used to build an inclusive classroom experience for international students. Second, we determined that the use of learner-centered instruction when implementing ePortfolios can lead to an increased sense of ownership, a deeper understanding, and a more inclusive environment for international students. Finally, by employing culturally responsive teaching principles in virtual exchanges, we established that students on both sides of an international exchange feel valued and included.

It is our hope that the incorporation of these technologies or practices will create a more positive, engaging experience for international students at U.S. institutions.

References

Bureau of Education and Research. (2011, March 22). Practical Classroom Strategies for Making Inclusion More Successful, Grades 6-12 [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RnxQCF3KFUo

Carter, D. F., Locks, A. M., Winkle-Wagner, R., & Pineda, D. (2006, April). “From when and where I enter”: Theoretical and empirical considerations of minority students’ transition to college. Paper presented at American Educational Research Association annual meeting, San Francisco.

Challis, D. (2005). Towards the mature ePortfolio: Some implications for higher education. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 31(3).

Cipollone, Maria & Schifter, Catherine & Moffat, R.A.. (2014). Minecraft as a creative tool: A case study. International Journal of Game-Based Learning, 4, 1-14. 10.4018/ijgbl.2014040101.

Edutopia. (2013, December 10). Using Minecraft as an Educational Tool [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SSimHPmZ0hA

Florian, L., & Rouse, M. (2009). The inclusive practice project in Scotland: Teacher education for inclusive education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25, 594-601.

Helm, F. (2015). The practices and challenges of telecollaboration in higher education in Europe. Language Learning & Technology, 19(2), 197-217.

Hundley, G., & Lambie, G. (2007). Russian speaking immigrants from the commonwealth of independent states in the United States: Implications for mental health counselors. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 29(3), 242-258.

Hyun, J., Quinn, B., Madon, T., & Lustig, S. (2007). Mental health need, awareness, and use of counseling services among international graduate students. Journal of American College Health, 56(2), 109-118.

Institute for International Education (2018). Open Doors 2018. Retrieved from https://www.iie.org/en/Research-and-Insights/Open-Doors/Data

Kalsner, L., & Pistole, M. C. (2003). College adjustment in a multiethnic sample: Attachment, separation-individuation, and ethnic identity. Journal of College Student Development, 44(1), 92–109.

Karsenti, T., Bugmann, J., & Gros, P. P. (2017). Transforming education with Minecraft? Results of an exploratory study conducted with 118 elementary-school students. CRIFPE: Montréal.

Lane, H. C., & Yi, S. (2017). Playing with virtual blocks: Minecraft as a learning environment for practice and research. Cognitive Development in Digital Contexts, 145-166. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809481-5.00007-9

Le, A. T., LaCost, B. Y., & Wismer, M. (2016). International female graduate students’ experience at a Midwestern University: Sense of belonging and identity development. Journal of International Students, 6(1), 128–152.

Lin, S. Y., & Scherz, S. D. (2014). Challenges facing Asian international graduate students in the U.S.: Pedagogical considerations in higher education. Journal of International Students, 4(1), 16-33.

Locks, A. M., Hurtado, S., Bowman, N. A., & Oseguera, L. (2008). Extending notions of campus climate and diversity to students’ transition to college. Review of Higher Education, 31, 257-285.

Lorezno, G., & Ittelson. (2005, July). An overview of E-portfolios. D. Oblinger (Ed). Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative.

Mesidor, J. K., & Sly, K. F. (2016). Factors that contribute to the adjustment of international students. Journal of International Students, 6(1), 262-282.

Microsoft Education. (2017, September 30). Play and Learn with Minecraft Education Edition [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WLxCi5NTD-A

Minecraft: Education Edition. (2016, November 10). One Educator’s Journey with Minecraft: Education Edition [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O81xH0CmLXE

O’Dowd, R. (2018). From telecollaboration to virtual exchange: State-of-the-art and the role of UNICollaboration in moving forward. Journal of Virtual Exchange, 1, 1-23.

O’Dowd, R., & Lewis, T. (Eds.). (2016). Online intercultural exchange: Policy, pedagogy, practice. Routledge.

O’Dowd, R. & Ritter, M. (2006) Understanding and working with ‘failed communication’ in telecollaborative exchanges. CALICO Journal, 61(2), 623–642.

Parkes, K. A., Dredger, K. S., & Hicks, D. (2013). ePortfolio as a measure of reflective practice. International Journal of ePortfolio, 3(2), 99-115.

Pexels. (n.d.). Beautiful Minecraft Photos · Pexels · Free Stock Photos. Retrieved from https://www.pexels.com/search/minecraft

Pixabay. (n.d.). Minecraft Images – Download Free Pictures. Retrieved from https://pixabay.com/images/search/minecraft

Poyrazli, S., Arbona, C., Nora, A., McPherson, R., & Pisecco, S. (2002). Relation between assertiveness, academic self-efficacy, and psychosocial adjustment among international graduate students. Journal of College Student Development, 43(5), 632–642.

Reese, M., & Levy, R. (2009, February). Assessing the future: E-portfolio trends, uses, and options in higher education. Research Bulletin, Issue 4. Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research.

Shannon-Ramsey, V., & Stevenson, A. P. (2018). Using virtual exchange to foster global learning experiences at HBCUs and other MSIs. Global Education & Minority Serving Institutions in U.S. Higher Education, 39.

The Mudpit. (2014, September 2). The Minecraft Pedagogy Pupilarium [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=MYAR8sBYFGc

Thomson, M. S., Chaze, F., George, U., & Guruge, S. (2015). Improving immigrant populations’ access to mental health services in Canada: A review of barriers and recommendations. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17(6), 1895-1905.

Unsplash. (n.d.). Minecraft Pictures | Download Free Images on Unsplash. Retrieved from https://unsplash.com/search/photos/minecraft

Wihlborg, M., Friberg, E. E., Rose, K. M., & Eastham, L. (2018). Facilitating learning through an international virtual collaborative practice: A case study. Nurse Education Today, 61, 3-8.