7 Chapter 7 – 2030: How MOOCs overcame criticism

Danek, D., & Hertzfeld, B.

2030: How MOOCs Overcame Criticism

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are a form of educational technology that is changing the way students, teachers, and educational institutions think about education. There have previously been many other educational technologies that have gained attention as being “game changers” in academic circles. Some of these educational technologies have included educational radio, language-labs, audience response systems, and learning management systems. A few of these educational technologies have matured into productive tools that remain in widespread use and others have failed to deliver on their full potential. In this chapter we will give an overview of the previous educational technologies that influenced MOOCs, review the current criticisms of MOOCs, and we will discuss how MOOCs may change based on current criticisms to become a success by 2030. This chapter intends to provide an overview of the evolution of MOOCs from creation, early adoption, refinement, to maturity. We have framed our chapter around the defining question: Have the current trending technologies (MOOCs) been successful and can the current technologies point the way to future successful next-generation tools?

What is a MOOC and how did we get here?

A Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) is defined as “a course of study made available over the Internet without charge to a very large number of people” (Oxford Dictionaries, 2019). The definition of exactly what is or is not a MOOC can be debated, but it is generally agreed that a MOOC is designed to have a large number of participants (massive), be open in registration and content (open), use the Internet for interaction and communication (online), and be focused on educating students (course). The term MOOC was coined by Dave Cormier in 2008 to describe an innovative course entitled Connectivism and Connectivity Knowledge (CCK08) (Cormier, 2008). The instructors planned the course to be non-traditional and follow the connectivism theory of learning as defined by Stephen Downes, “knowledge is found in the connection between people with each other and that learning is the development and traversal of those connections” (Harasim, L. 2017, p. 95). CCK08 as implemented by Stephen Downes and George Siemens, used online tools to encourage interactions between students as part of the learning process. Students enrolled in the course participated as learners and teachers through participation and self-reflection.

The CCK08 course enrolled approximately 2,300 students; 25 students paid tuition to obtain a Certificate in Adult Education but many more attended the course as an ‘open participation’ student for free. The CCK08 course did not have a formal course design, “Cormier and Downes approached it as an informal experiential event in which the participants would engage in a form of self-directed online learning, pursuing their own interests and connecting with others as they wished” (Harasim, L. 2017, p. 94). The CCK08 course eschewed the more traditional learning management software used at universities and instead utilized ‘open content’ (free online resources, services, and platforms) for course technology such as blogging software, RSS feeds, and online forums.

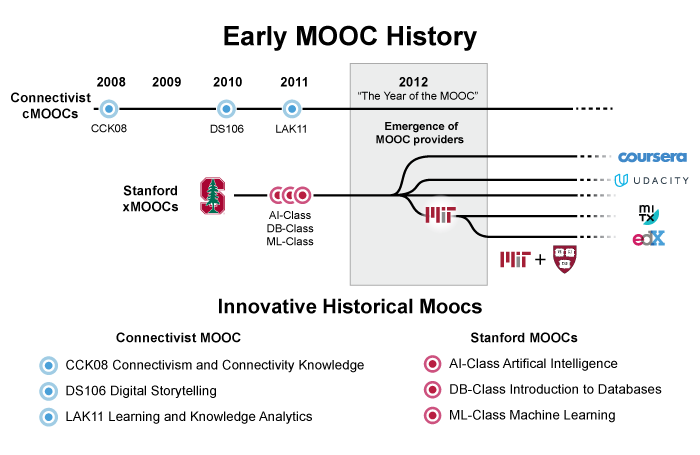

The CCK08 course created a lot of academic interest in its use of non-structured learning. Additional courses were later created and held in 2010 and 2011 using the same connectivist approach to collaborative online coursework. (see Figure 1). After a series of connectivist MOOCs were held large universities took note of this new practice and started to design a new generation of MOOCs. These MOOCs focused on delivering top university course content in the new MOOC style of online delivery. This new generation of MOOCs were designed and run by prestigious universities like Harvard, MIT, and Stanford. Their course designs focused on delivering a more traditional university style classroom structure as compared to the unstructured connectivist MOOCs. “[George] Siemens introduced the terms cMooc and xMooc in his 2012 blog, to differentiate two types of MOOC offerings: cMOOCs were distinguished as based on ‘ideology’ whereas, according to Siemens, xMOOCs were well-funded, for-profit enterprises”. (Harasim, L. 2017, p. 96). The newer style of xMOOCs tended to be based around a professor (often high-profile), they used custom designed course software to collect “big data” about their participants and their performance, they allowed for more immediate feedback to the student or professor, and focused on the “transmission of information” (Harasim, L. 2017, p. 97). Many xMOOCs also retained some of the features of cMOOCs, like peer discussion and collaboration. Figure 1 shows the timelines of the two main branches of MOOCs, the relationship universities had to the xMOOC movement, and the commercialization of MOOCs that happened in 2012 during the “Year of the MOOC” (Pappano, 2012).

MOOCs as a whole, whether a cMOOC or an xMOOC, have both embraced using modern course delivery methods to take learning outside of the traditional classroom. MOOCs have received a lot of media attention as a possible solution for the many challenges that plague current educational systems. Like many previous emerging educational technologies MOOCs have seen a lot of hype and excitement around their potential. To fully understand the potential of a new technology like MOOCs it is important to distinguish between the technologies hype and its potential for mainstream viability.

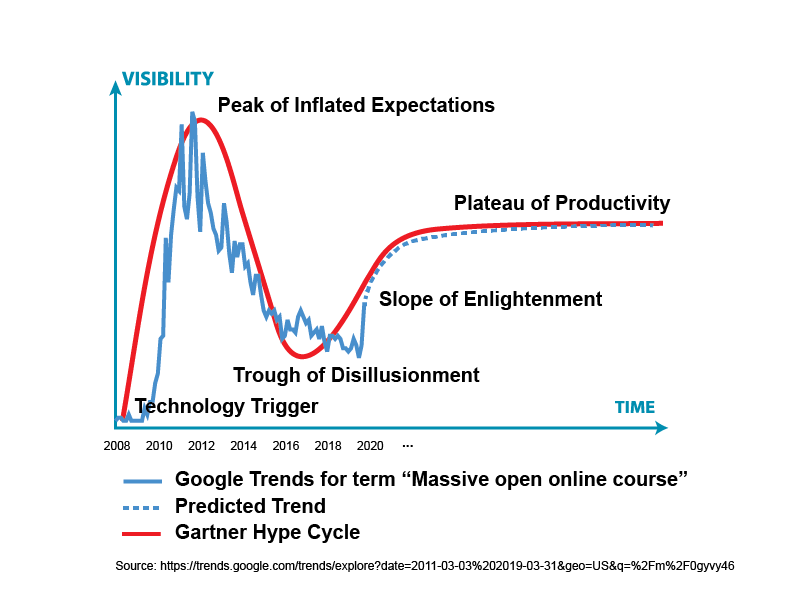

To determine the viability of MOOCs it is helpful to view the technology in relationship to the Gartner Hype Cycle. The Gartner Hype Cycle measures a technology based on five key phases labeled: the innovation trigger, the peak of inflated expectations, the trough of disillusionment, the slope of enlightenment, and the plateau of productivity. Gartner states the “Gartner Hype Cycles provide a graphic representation of the maturity and adoption of technologies and applications, and how they are potentially relevant to solving real business problems and exploiting new opportunities” (Garner, 2019). Shown in Figure 2, the Gartner Hype Cycle chart is overlaid with Google Trends data for the topic “massive open online course”. This chart shows a representation of the hype MOOCs have generated over time based on search queries. Figure 2 shows that the MOOC topic was heavily trending leading up to the larger universities designing and releasing their first xMOOCs in 2012 as shown in Figure 1. After the initial peak of inflated expectations in 2012 the topic’s trending rate declined. This decline is potentially from interest waning as the early xMOOCs failed to deliver all of their promises and criticisms for the technology started to develop.

The History of Educational Technology

Throughout history there have been many tools used in education. These tools are collectively called educational technologies. Educational Technologies are defined by, “the study and ethical practice of facilitating learning and improving performance by creating, using, and managing appropriate technological processes and resources” (Richey, Silber, & Ely, 2008). Early educational technologies included cave paintings, abacuses, and writing slates. As human civilization advanced so to did our educational technologies. Books, audio, video, and computers are all examples of inventions that contributed to the advancement of educational technologies. As new technologies continue to be developed over time they are assessed and appropriated into pedagogical practices with the goal of facilitating learning and improving performance. Understanding the history of technology adoption in education is critical to understanding the history of MOOCs from emerging technology to maturity.

MOOCs as an educational technology utilize precursor technologies. Individual educational technologies have their own advantages and disadvantages. Over time as educators learn to use the new tools best practices will be developed and the technology will mature. By their very nature MOOCs take advantage of the rich history of educational technologies that came before them. Instructors may choose to use different technologies in their MOOCs to serve different purposes. This mix and match approach to course design means that instructors must be well versed in the tools available to them as well as each technologies educational best practices and pedagogy.

In the following timeline we show a selection of educational technology precursors that have influenced MOOCs or are commonly used in MOOCs.

The Rise of the MOOCs

In a 2012 article titled The Year of the MOOC, the general thought was that the format of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), would serve as a disrupter to traditional education. EdX, Coursera, Udacity and the Khan Academy were paving the way for what looked like could be a significant transformation in education. EdX had 370,000 students registered for their courses, Coursera had reached 1.7 million students, and Udacity had 150,000 students registered in a single course. One course on Coursera, which then moved to EdX, 75% of the participants were from outside the United States (Pappano, 2012). The hope was that these courses would reach the masses and also earn some accreditation. As Dr. Anant Agarwal predicted in 2012, ““a year from now, campuses will give credit for people with edX certificates” (Pappano, 2012). The course format allows for many people to access the course without having to travel to a university. This could lead to a significant increase in global education, as more people could access high-quality education. Adding to this accessibility, is the free cost of the courses. If courses offered in this format are recognized by employers and universities, it may lead to lower tuition costs for traditional education.

As Dr. David Stavens stated in 2012, “we are only 5 to 10 percent of the way there” (Pappano, 2012) to the disruption MOOCs could have on traditional education. Even in 2012, there were concerns about who was registering for courses, grading coursework and evaluating courses, and accreditation for courses (Pappano, 2012). In the years following, MOOCs did not immediately achieve the success that people thought they would. However, it may not mean that MOOCs can never achieve that success. In the following sections, we will look at the current criticisms of MOOCs and discuss what we predict can happen by 2030 to make MOOCs the truly revolutionary tool that most thought they would be. Through our research, we have found that we might not be that far off from overcoming some of these barriers. Technology is continuing to develop at a rapid pace, which will help to overcome access issues and it appears that there is some change to the way companies view formal education, which may help to make MOOCs a viable addition to, or substitute for, formal university education.

MOOC Criticisms and Barriers to Overcome

Who Creates the Content?

Much of the criticism of MOOCs centers around the fact that a majority of content for MOOCs is typically created by western cultures, continuing to push western colonization. One study suggests, that while many groups are able to participate in MOOCs, there is an Anglo-American perspective domination of discussion threads. The author goes on to say that while others could challenge the Western worldview at times, “Anglo-American voices and arguments were most common” (Sparke. 2017 p. 61). While MOOCs are becoming more popular in other languages, there is a higher number that require proficiency in the English language. It is also worth noting that the majority of participants in MOOCs are male (Sparke, 2017). So when looking at a cMOOC, designed to allow participants to connect and share ideas across continents and cultures, it appears that a white, male, English voice is producing a majority of the content. As for the xMOOC, the high-profile professor putting on the course will likely match this demographic.

2030: Content Creation for MOOCs

In 2030, courses will be offered in more languages with content produced and delivered from people all over the world. Adding a true global perspective to classes that help spread more diverse ideals. By allowing more marginalized populations to produce the content, it will allow for more authentic perspectives. Courses will not have a western spin to them, content will be authentic. Much of this stems from awareness in the current state. Making potential biases known will help to combat them and create a more inclusive environment.

From a technology perspective, translation technologies will allow participants who speak different languages to connect and also allow people to create content in their language and voice and allow others to consume that content in their native language. This allows participants to have an authentic dialogue with peers, with the confidence of speaking their native language. From a content creation standpoint, the learner will be able to complete their work in their native language and the leader of the MOOC can use technology to grade the project.

And the reverse is true, as well. Students from western cultures will need to be prepared to learn from non-western perspectives. We may see courses within a MOOC that act as a primer for students in the course to help them understand what to expect from their instructor. For example, if an Iraqi teacher is leading a course, there may be a primer on Iraqi values, educational views, and social constructs. This may help to make sure that students feel comfortable in the course and are not disengaged if a teachers views and thoughts around education are different from their own. The primer may help to lead students to respect these cultures that are different from their own, and in turn help them to be more receptive to learning.

In order to achieve a more universal perspective in MOOCs around the world, a more connected world in terms of internet access was needed to reach these levels of openness.

Who Can Access MOOCs?

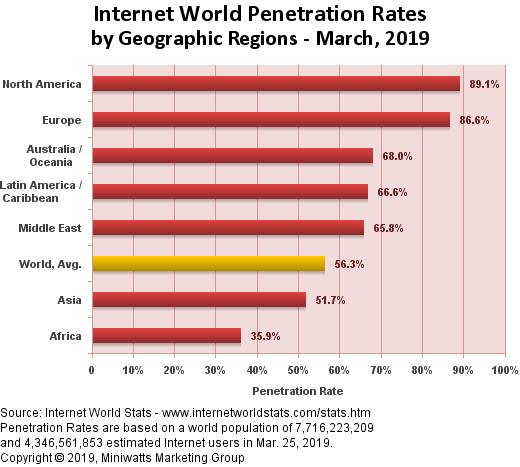

Inherently, for an online course to work, participants will need internet access. While a majority (56.3%) of the world has access to the internet, as seen in the figure below (Miniwatts Marketing Group, 2019), there are still a lot of regions that are still limited in their access. While much of the world can access the internet, and in turn courses, more work is needed to break down the digital divide. In looking at the chart below, you’ll notice that internet penetration is highest in North America and Europe. At above 80%, these regions are much higher than the next closest regions and significantly higher than the world average of 56.3%. It is fair to say that individuals in these regions can more easily access MOOCs and also create more content. In either an xMOOC or a cMOOC, North Americans and Europeans have a monopoly on the market, so to speak. While others can still participate, it is likely that they are participating in lower numbers.

Much of the access to the internet is concentrated in the wealthier, more developed regions of the world. Ironically, while much of the developed world has access, there is still room for improvement. And as the chart indicates, two of the the largest land masses, with large populations, have the lowest internet penetration levels. Accessing the internet is only the beginning. It will also be important that students with access have access to a quality, stable high-speed connection. Coursework will likely consist of video lectures and online discussion. Students will need a high-quality connection to ensure that they can smoothly play these video lectures and participate in engaging and close to real-time discussions.

Starting between 2016 and 2019, Facebook and Amazon were both looking at ways to increase internet access around the globe. Facebook was testing a solar-powered drone to spread internet access (Russell, 2019), while Amazon was looking to launch a network of connected satellites that would expand internet access around the world (Sheetz, 2019). These tech giants have likely started this work as a means to grow their businesses, but is an important step in the right direction to overcoming the digital divide. While the work has been started, there is more to be done as we move towards 2030.

2030: Access to MOOCs

In 2030, with the advent of 5G (or even 6G or 7G) cell service and significant investment from corporations around the world, more of the world has consistent access to the quality, high-speed internet needed to participate in MOOCs. As noted above, corporations in the United States had started this work, but with significant buy-in from governments around the world, a truly connected world was realized by 2030. Initially, governments were concerned that with this access created by the likes of Facebook and Amazon, they’d monopolize their products and services on the internet that was provided. But while these corporations laid the groundwork, the work of non-profits was needed to help bring this access to remote areas. Along with having the access to the internet, remote populations would still require the computers or tablets needed to access the internet. As the technology became more common and affordable, policy makers were able to see the benefits in providing internet access for all.

With the trends of increasing hiring remote associates and allowing associates to work from home, governments were able to see the economic benefit of helping to educate their populations through MOOCs. By allowing them to educate themselves at home and citizens do not have to leave the country to go to university. Helping to promote internet access for all allows countries to help limit brain drain from taking the educated away from their country. It also helps to keep citizens at home, working remotely for large corporations, keep their wealth in the country to support local economies.

This access makes MOOCs more open to all and allows students and gives them the chance to become content creators. Looking back to the prior section, an increase in access will allow more diverse group to bring their perspective to the table. These unique perspectives will add to the overall success of the course.

With increased access and more broadly produced content, MOOCs were able to see an increase in both quality and completion rates across the world.

Completion Rates

Without the incentive to finish because of tuition being paid, MOOCs experience low completion rates for their courses. Typical enrollees tend to be “mostly white, mostly middle class, mostly male, and mostly already university-educated” (Sparke, 2017 p. 53). With a student base that is already educated and has not paid tuition, it is understandable that they would have little incentive to finish the coursework. If the content becomes too much, repetitive or unrelated to the course, it could deter the student and lead to low completion rates. The lack of investment in tuition payments does not draw them back to the course. Formal education is viewed as an investment for most individuals and we have seen the cost of traditional education rise. The thought with MOOCs is that the openness (no tuition) would help more people to access education and in turn, drive down the costs of traditional education. It appears, however, that this did not immediately occur.

In 2015, the MOOC platform Coursera began partnerships with BNY Mellon, Cisco, Microsoft and other companies to create courses for employees to provide certifications in fields like data science, computer programming, and finance (Vander Ark, 2015). With the help of these corporations, Coursera is able to create courses that help to ensure that the student walks away with the skills that companies need. This model can also be applied to continuing education for educators, as these credentials allow for targeted, job-specific skill sets – “No more random courses for continuing ed credits, just highly relevant job-linked learning” (Vander Ark, 2015).

2030: Completion Rates

In 2030, organizers and content creators for MOOCs work closely with companies around the world to develop materials that are relevant for workers, providing them with the skills that companies need to drive growth. Working with established MOOC platforms and universities allows companies to ensure that employees and prospective employees are getting the education needed. By continuing this work from Coursera in 2015, companies have solved for the concern that MOOCs may not be provided by an accredited institution. These partnerships help to ensure that a quality product is being produced, from a trusted source.

With this partnership, and corporations being at the forefront of which courses are being produce, micro-credentialing is more respected as a degree alternative. A series of micro-credentials in coding, taken right after or during high school, will have an individual prepared for the workforce. This allows workers to join the workforce sooner and companies know that their new employee has the skills needed to produce in their role. In 2030, companies are able to utilize MOOCs as a recruiting tool, to identify and pursue talented individuals to join their organization. To combat any privacy issues, participants in the MOOC consent to the recruiting services that are provided.

For the student that is not already in the workforce, completion of a course or a series of courses for a certificate will be automatically updated on the student’s digital resume. As this is updated, open roles that desire this skill set can be shown to the student and this information could also be sent directly to companies. These services will help the job seeker to connect with various companies, building a network of potential jobs when they are ready to enter the workforce. They may graduate with a degree from a University and certificates in coding and project management from a MOOC. Helping to make them more desirable in the job market. Finding gainful employment is a strong incentive to complete coursework.

With courses that are relevant to a workers’ current role (or role that they desire) or helpful in achieving the next promotion, MOOCs are able to overcome their low completion rates. Participants now have the incentive (a salary or salary increase) to complete the coursework.

Revenue and Sustainability

It has been argued that MOOCs will be an important tool in lowering the cost of education by being cost efficient and providing global access (Turner & Gassaway 2018). To scale up access to MOOCs a number of new platforms were created in 2012. Coursera, Udacity, and EDx were some of the first platforms to launch in 2011 and 2012. Coursera and Udacity are both commercial platforms founded by professors involved in the early Standford xMOOCs. EDx was founded by Harvard and MIT and operates as a nonprofit organization. The early MOOC platforms required financial investors to get off the ground, in turn these investors required solid business models to be implemented to provide revenue and sustainability. These new business interests often have been at odds with the openness of what MOOCs were initially purported to be (Straumsheim, 2016). As MOOC platforms searched for sustainable business models, they have in many cases had to limit access with paywalls, tiered pricing models, time limits, or fees for certificates. Additionally, some for-profit providers started to pivot to the more profitable professional development and corporate training sectors. The nonprofit MOOC providers like EDx have needed to create partnership agreements with other universities who help to fund their ongoing operations. The long term sustainability of these business models has been called into question by critics based on the high number of registrations but low completion rates and reluctance of industry to value MOOC completion certificates.

2030: Revenue and Sustainability

By the year 2030 MOOCs will have overcome their revenue and sustainability criticisms by adapting to their environment. Early MOOCs were experimental in nature and were not created with a business model in mind. Once the idea of MOOCs went mainstream and early MOOC faculty from Standford started to build their private platform startups, future revenue streams and sustainability became a much more important part of how MOOCs were designed and delivered. At first the private platform companies raised venture capital from private equity firms, Coursera raised $210.1M and Udacity raised $160M in funding (retrieved 2019). The initial rounds of funding helped these fledgling companies to build out their platforms, hire staff for course creation, and develop strong management teams. The venture capital firms helped provide valuable expertise to the startups to build solid business plans. In the first five years the private companies were able to iterate on course design, revenue models, and enter new markets like training and development. Once financially viable business models were established more institutions started to participate and the number of courses offered grew rapidly.

edX was the only early MOOC platform to be formed as a non-profit partnership between MIT and Harvard. edX focused on institutional partnerships with universities around the world. Many of these partnerships were funded by governments who were interested in offering online courses for their citizens. The governmental involvement increased pressure for standardization of credentialing and certification across different courses and platforms. The governmental backing of MOOCs gave them more prestige and value to employers than they had previously. The governmental partnerships also encouraged universities to participate in a new landscape where government approved for-profit MOOC courses were required to be accepted for credit at universities. These new rules increased the competition for student dollars between MOOC providers and traditional universities who now needed to compete to remain viable.

Student Authentication and Credentialing, Badges, and Accreditation

One advantage MOOCs have had over traditional courses is how easy it is to register to become a student. This ease of access has made MOOCs an important tool in widening access to higher education regardless of a student’s socioeconomic status or location. As MOOCs have struggled to become a mainstream educational practice, they have had to prove that they provide added value to employers by producing highly qualified job candidates. Common criticisms of MOOCs in this regard relate to, how do employers verify who the student is that attended the MOOC? and how do students provide proof that they have the skills required for a job? Employers looking for qualified candidates for positions want to ensure that a student’s education has been provided by institutions with established and well regarded programs. It has been difficult for MOOCs, with their relatively short existence, to have a track record that employers accept.

2030: Student Authentication and Credentialing, Badges, and Accreditation

By 2030 the use of MOOCs in higher education has become mainstream. At traditional universities freshman level lecture hall courses have been replaced by MOOCs and students attend remotely. These xMOOC styled courses have been integrated directly into the standard curriculum. Universities have widely opened these introductory courses to the general public for marketing purposes and to encourage prospective students to enroll at their school. Prospective students who pass with an advanced score can receive preferential admissions and course credit for a reduced fee.

MOOC providers who are not part of traditional university programs work with education agencies to validate their programs. Many MOOC providers start to offer supplementary course content for k-12 programs. This supplementary content is designed to follow state curriculum and is purchased by state agencies to provide standardized high quality primary and secondary student instruction which can be used by students while in school or at home.

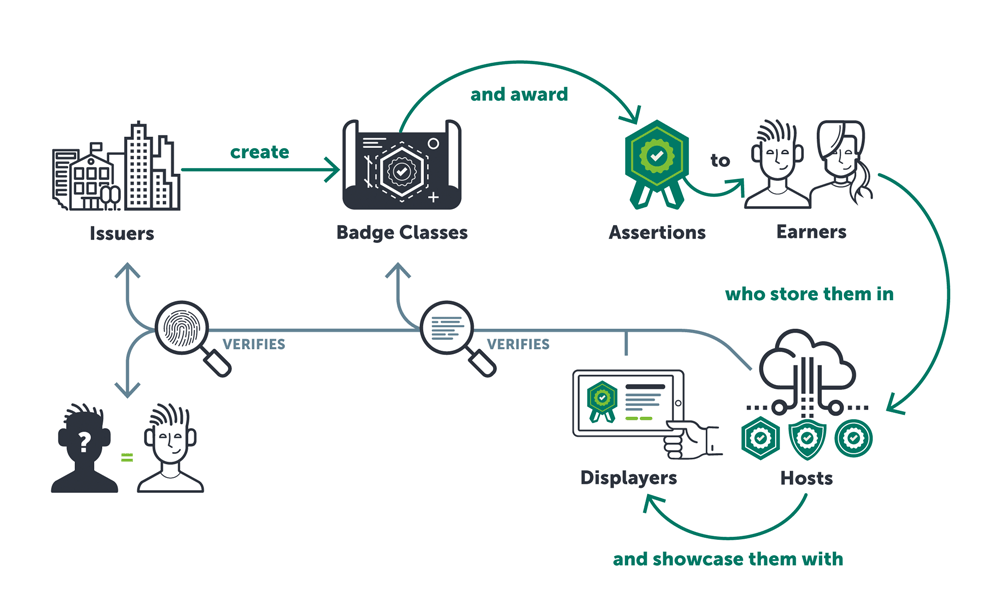

To manage the complexities of accrediting MOOC providers and programs across primary, secondary, and higher education new tools are needed. Education agencies standardize on using the Open Badges specification. The Open Badges specification allows for the verifiability, portability, reliability, and discoverability (Imsglobal.org, 2019) of an individual student’s educational achievements. Education providers issue Open Badges to eliminate many of the difficulties in verifying individuals students and their lifelong learning. Universities form partnerships that allow students to select Open Badge courses from any institution when proper requirements are met. The Open Badges issuing institutions issue and verify credentials and prove their own accreditation through cryptographically signed certificates issued by governmental educational agencies. The governmental educational agencies regularly audit institutions to ensure they meet minimum student verification standards and their courses meet the assertions made in the badges they issue.

Students have access to online tools to select and display their earned badges relevant to positions they are interested in. Students can issue a custom view of badges for each job position they apply to. Potential employers use Open Badges to verify an applicant’s qualifications based on the Open Badge assertions and quality of the issuing institution. As Open Badges features become widely used universities start to issue their own Open Badges for all course content and degrees.

Conclusions

While Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have not immediately transformed education as the hope was in 2012, as we have outlined above, we are not too far off from this reality. In a recent meeting of the American Workforce Policy Advisory Board, Apple CEO Tim Cook discussed “the mismatch between the skills that are coming out of colleges and what the skills are that we believe we need in the future, and many other businesses do, we’ve identified coding as a very key one” (Eadicicco, 2019). With these comments from Mr. Cook and corporations, including Apple, Google, IBM, and Bank of America, not requiring a college degree for certain jobs, we may be entering a period of time where certifications from MOOCs could be looked at favorably (Eadicicco, 2019). As corporations are recognizing that there are skills needed to perform certain jobs and universities are not teaching those skills, MOOCs may present an opportunity to fill those gaps. Providing students with the skills they need to perform in jobs that companies need to fill. This paradigm shift from corporations could be the trigger to start making some of our predictions above, realities. If the US can lead the way in providing high-quality coursework in the form of MOOCs, developing countries may follow suit. Seeing the benefits of educating their populations, they could support high-speed internet access for their populations to allow for access to MOOCs.

References

8 Lessons from 20 Years of Hype Cycles. (2016). Linkedin.com. Retrieved 19 April 2019, from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/8-lessons-from-20-years-hype-cycles-michael-mullany

Bennett, R., &Kent, M. (2017). Massive Open Online Courses and Higher Education : What Went Right, What Went Wrong and Where to Next? New York: Routledge. Retrieved from http://proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1511256&site=ehost-live

Billsberry, J. (2013). MOOCs: Fad or Revolution? Journal of Management Education, 37(6), 739–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562913509226

Cormier, Dave. “The CCK08 MOOC – Connectivism Course, 1/4 Way.” Dave’s Educational Blog, 2 Oct. 2008, http://davecormier.com/edblog/2008/10/02/the-cck08-mooc-connectivism-course-14-way/

Eadicicco, L. (2019). Apple CEO Tim Cook explains why you don’t need a college degree to be successful [Web Article]. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/apple-ceo-tim-cook-why-college-degree-isnt-necessary-2019-3

Hype Cycle Research Methodology. (2019). Gartner. Retrieved 19 April 2019, from https://www.gartner.com/en/research/methodologies/gartner-hype-cycle

Harasim, L. (2017). Learning Theory and Online Technologies. Retrieved from http://books.google.com

Hill, Phil (2013, October 12). MOOC timeline [Digital image]. Retrieved April 19, 2019, from https://mfeldstein.com/mooc-history-presented-aacn13-conference/

Innovating Pedagogy 2019: Open University Innovation Report 7. (2019). Retrieved from http://proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsbas&AN=edsbas.658A784B&site=eds-live&scope=site

Open Badges 2.0 Implementation Guide. (2019). Imsglobal.org. Retrieved 19 April 2019, from https://www.imsglobal.org/sites/default/files/Badges/OBv2p0Final/impl/index.html

Miniwatts Marketing Group. (2019). World Internet Users Statistics and 2019 World Population Stats [Webpage]. Retrieved from https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm

Mirrlees, T., & Alvi, S. (2014). Taylorizing Academia, Deskilling Professors and Automating Higher Education: The Recent Role of MOOCs. Journal For Critical Education Policy Studies (JCEPS), 12(2).

Pappano, L. (2012). The Year of the MOOC. Nytimes.com. Retrieved 19 April 2019, from https://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/massive-open-online-courses-are-multiplying-at-a-rapid-pace.html

Richey, R. C., Silber, K. H., & Ely, D. P. (2008). Reflections on the 2008 AECT Definitions of the Field. TechTrends, 52(1), 24-25. Retrieved 15 April 2019, from https://thenextnewthing.files.wordpress.com/2009/11/aect-definitions-of-the-field.pdf

Russell, J. (2019). Facebook is reportedly testing solar-powered internet drones again – this time with Airbus [Web Article]. Retrieved from https://techcrunch.com/2019/01/21/facebook-airbus-solar-drones-internet-program/

Sheetz, M. (2019). Here’s why Amazon is trying to reach every inch of the world with satellites providing internet [Web Article]. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2019/04/05/jeff-bezos-amazon-internet-satellites-4-billion-new-customers.html

Sparke, M. (2017). Situated cyborg knowledge in not so borderless online global education: Mapping the geosocial landscape of a MOOC. Geopolitics, 22(1), 51-72.

Straumsheim, C. (2016). Critics see mismatch between Coursera’s mission, business model. [Web Article] Insidehighered.com. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/01/29/critics-see-mismatch-between-courseras-mission-business-model [Accessed 22 Apr. 2019].

Turner, R. L., & Gassaway, C. (2018). Between kudzu and killer apps: Finding human ground between the monoculture of MOOCs and online mechanisms for learning. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 1-11.

Vander Ark, T. (2015). Micro-credentials: the future of professional learning [Web Article]. Retrieved from https://www.gettingsmart.com/2015/09/micro-credentials-the-future-of-professional-learning/