9 Chapter 9 – Behavior change using health apps

McCann, S.

Section 1: Physical Activity Promotion

Health Education focuses on mobile applications utilized for the promotion healthy behaviors. One primary focus of health education is to builds knowledge, skills, and positive attitudes about health with the intent of improving health and preventing disease. Due to a similar goal of creating, promoting, and maintaining positive health behaviors through technology, research is provided to support Behavior Change Techniques (BCTs) use for encouraging physical activity is included relative to the quality and effectiveness of app design.

The primary question for this section of the health education chapter is are mobile apps targeted to children, adults, and families effective for health behavior promotion through integration of BCTs. Some of information should apply to design and features used by health educators with a similar goal of improving health behaviors through integrated use of technology into educational curricula. Additionally, consideration of long term health implications attributed to health promotion technology may be of interest if similar features are being used in apps targeted for adults and adolescent groups.

The Center for Disease Control recommends health education ” that help students develop the knowledge, attitudes, behavioral skills, and confidence needed to adopt and maintain physically active lifestyles.” Specific skills mentioned were behavior change techniques such as decision making, goal setting, identifying and managing barriers. There are a total of 93 BCTs categorized within 16 areas that could potentially be used within wearable and apps to but only 15 are commonly mentioned in research regarding the physical activity promotion (Lyons, Lewis, Mayrsohn, & Rowland, 2014). The following BCT have been successful in promoting physical activity.

| BCTs Attributed to Change in Physical Activity Levels |

|---|

| Practice |

| Action planning |

| Barrier identification/problem solving |

| Facilitate social comparison |

| Goal-setting/intention formation |

| Prompt rewards contingent on effort or progress towards behavior |

| Provide feedback on performance |

| Provide information on consequences of behavior in general |

| Provide instruction |

| Review of behavioral goals |

| Self-monitoring of behavior |

| Self-rewards |

| Self-talk |

| Social support |

| Teach to use prompts/cues |

Starting Point of Crisis

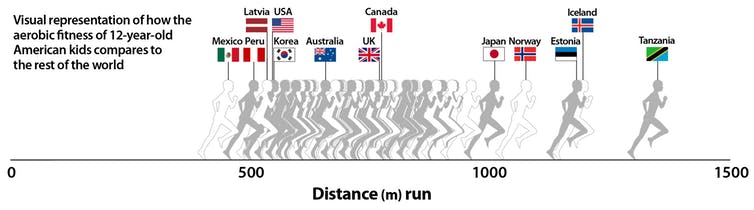

The aerobic fitness levels of over 1.1 million kids aged 9 to 17 years from 50 countries shows American children are falling behind at an alarming level which continues to decline as age increases (Lang, Tremblay, Léger, et al., 2018).

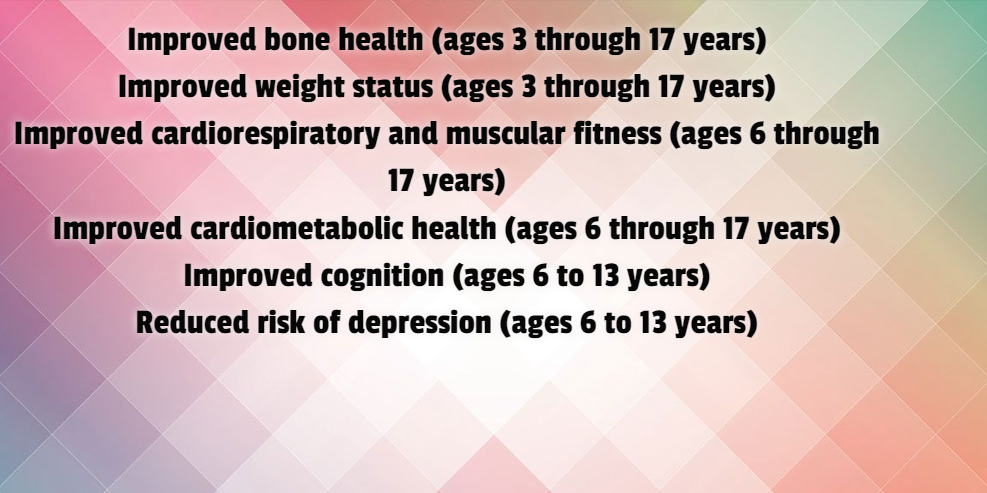

Physical activity is widely known to decrease cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in the future, but children continue to experience rising obesity levels. Most children and adolescents do not achieve the recommended minimum amount of daily physical activity. Encouraging physical activity at an early age to develop healthy habits that can progress into adulthood is important for preventing disease. Childhood and adolescence

are key periods of interest because these are potentially

important times where patterns of obesogenic

behaviors are created; such as poor eating habits, low physical activity, and sedentary behaviors (Leech, McNaughton, & Timperio, 2014).

“Several studies reported that cardiorespiratory fitness in childhood and adolescence is a predictor of CVD risk factors, such as abnormal blood lipids, high blood pressure, and excess of overall and central adiposity later in life” (Ruis et al., 2009, p. 918).

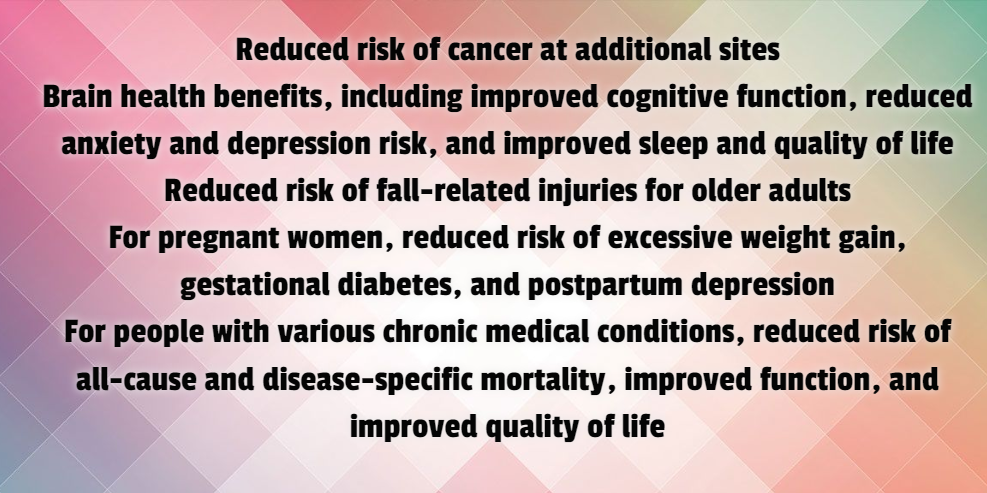

Evidence continues to suggest that sedentary behavior, independent of any other risk factors, is strongly associated with negative health outcomes in children ages 5-17 (Tremblay et al., 2011). 117 million adults—have one or more chronic diseases and 7 out of the 10 most common chronic diseases are positively impacted by regular physical activity (Piercy et al., 2018). When considering ages 11-17, research consistently supports the finding of adolescents and girls having lower physical activity levels, but a evidence for a cumulative effect of unhealthy behaviors on obesity is inconsistent (Leech, McNaughton, & Timperio, 2014). Sedentary behavior is a significant risk factor for several chronic lifestyle conditions which are of higher risk of mortality among women (Kinsey, Whipple, Reid, & Affuso, 2017).

Sedentary behavior research, assessed primarily through increased TV viewing, found that more than 2 hours per day was associated with poor body composition, lower fitness, decreased scores for self-esteem and pro-social behavior and lower academic achievement among ages 5-17 years (Tremblay et al., 2011). However, several benefits are attributed to regular physical activity for both adults, children and adolescents.

Design Matters

Apps are big business with global revenues rising from 69.7 billion in 2015 to a projected 188.9 billion for 2020 with an estimated 3.7 billion mobile health app downloads in 2017 (statistica.com); however, without a sound design and functionality they are destined to being replaced. Most physical activity game apps included in research from 2015-2019 show a steep decline in consistency and overall continued availability as more options come about. One feature shown to work in increasing physical activity is use of BCT to enhance user engagement (Patel, Asch, & Volpp, 2015). Below is a chart of common BCTs frequently used in apps.

| Behavior Change Techniques | Use in Physical Activity Apps |

|---|---|

| Provide instruction on how to perform behavior | Very Frequently |

| Model/demonstrate the behavior | Very Frequently |

| Provide feedback on performance | Frequently |

| Goal settingbehavior | Frequently |

| Plan social support/change | Frequently |

| Information about others approval | Frequently |

| Goal settingoutcome | Frequently |

| Prompt review of behavioral goals | Occasionally |

| Facilitate social comparison | Occasionally |

| Prompt review of outcome goals | Occasionally |

| Set graded tasks | Occasionally |

| Provide information on where and when to perform the behavior | Occasionally |

| Prompt self-monitoring of behavior | Rarely |

| Prompt self-monitoring of behavioral outcomes | Rarely |

| Teach to use prompts/cues | Rarely |

| Prompt rewards contingent on effort or progress toward behavior | Rarely |

| Provide rewards contingent on successful behavior | Rarely |

| Action planning | Rarely |

| Information on consequences of behavior to the individual | Very Rarely |

| Prompting focus on past success | Very Rarely |

| Information on consequences of behavior in general | Very Rarely |

| Stimulate anticipation of future rewards | Very Rarely |

| Environmental restructuring | Very Rarely |

| Normative information about others behavior | Very Rarely |

| Relapse prevention/coping planning | Very Rarely |

| Shaping | Very Rarely |

| Agreeing to a behavioral contract | Never |

| Barrier identification/problem solving | Never |

| Fear arousal, prompting anticipated regret | Never |

| General communication skills training | Never |

| Prompting practice | Never |

| Role model/position advocate | Never |

| Stress management/emotional control training | Never |

| Motivational techniques: imagery, self-talk, motivational interviewing | Never |

| Time management | Never |

| Use of follow-up prompts | Never |

In apps used to improve diet, physical activity, and sedentary behavior which are primary features of apps used for adults, an average of 6 BCTs were identified per app; the most frequently used BCTs were providing ‘instructions’, ‘general encouragement’, ‘contingent rewards’, and ‘feedback on performance’ (Schoeppe et al., 2017); researchers again found an average of 6.6 BCTs per app which ranged from 1 to 21 BCTs, and most BCTs in the taxonomy were not represented in any apps (Conroy, Yang, & Maher, 2014). On the lower end, between one and 13 behavior change techniques (mean=4.2, SD=2.4, median=4) were noted in research of top apps in 2009 (Fox & Duggan, 2010).

Researchers found physical activity promotion implemented an average of approximately eight techniques and five primary functions (Mollee, Middelweerd, Kurvers, & Klein, 2017). Mollee et al. (2017) grouped functionality categories revealed that 83-95% of analyzed apps include at least on feature related to Measuring and Monitoring, Information and Analysis, and Support and Feedback. Although it should be noted that descriptions of apps are also not consistently user friendly and a lot more information can be gained from websites or downloading the app itself (Conroy, Yang, & Maher, 2014; Yang, Maher, & Conroy, 2015). Internet based interventions maintain behavior change and symptom improvement via nine nonlinear steps that focus on the user, environmental factors, and website characteristics (Ritterband et al., 2009).

Key Takeaways (Mollee, et al., 2017)

Most prevalent features of successful apps

- User input capability

- Textual/numerical overviews of user progress

- Sharing achievements or workouts in social media

- General advice on physical activity

- Reviews correlate features with app attractiveness

- No correlation with features and functionality

Knowledge of internet based interventions, provides context on mechanisms of change that should be considered when referring to online interventions, such as social media, for a desired behavior change. Additionally the use of hand-held technology is on the rise and children are often multitasking in use of multiple devices which makes wearable devices a great options. Wearable devices used in conjunction with mobile apps have become popular in physical education courses, among student athletes, and the general public for group or personal use.

Wearable Devices

Along with the increase in popularity among integrating social media access among apps is the use of wearable devices to combat sedentary behaviors (SB). Common sedentary activities noted in research are playing video games, using the computer for non-school work, or prolonged sitting (Tremblay et al., 2011). In a comparison of 13 wearable activity trackers, all trackers helped users to self-monitor behavior, obtain feedback on behavior, and add objects to the environment while also generally supporting users in goal setting and comparing behavior with their goal (Lyons et al., 2014).

“BCTs most commonly found in wearable activity trackers are self-monitoring and self-regulation techniques which are more likely to appeal to younger and middle-aged adults, while BCT to overcome barriers are better for older adults” (Mercer et al., 2016).

In a study evaluating wearable devices, the preferences (likeability) of adolescent girls and women focused on visual display of movements and ease of navigation (Kinsey, Whipple, Reid, & Affuso, 2017). Designers should also consider common dislikes relative to missing common functions like calorie tracking, appearance, backlight, length of battery life, color, and not waterproof (tied for girls) and vertical time display which were evaluated for Movband (Kinsey et al., 2017).

DHS Group gives schools Movband, which works with HealthSpective mobile app to track step counts “to facilitate teaching students and can be used to reward Increased activity levels and develop healthy habits that last a lifetime” (http://www.dhsgroup.com).

Other wearable devices that include BCT, an average of 9 techniques in each and also all include an optional social component, are shown below (Mercer et al., 2016).

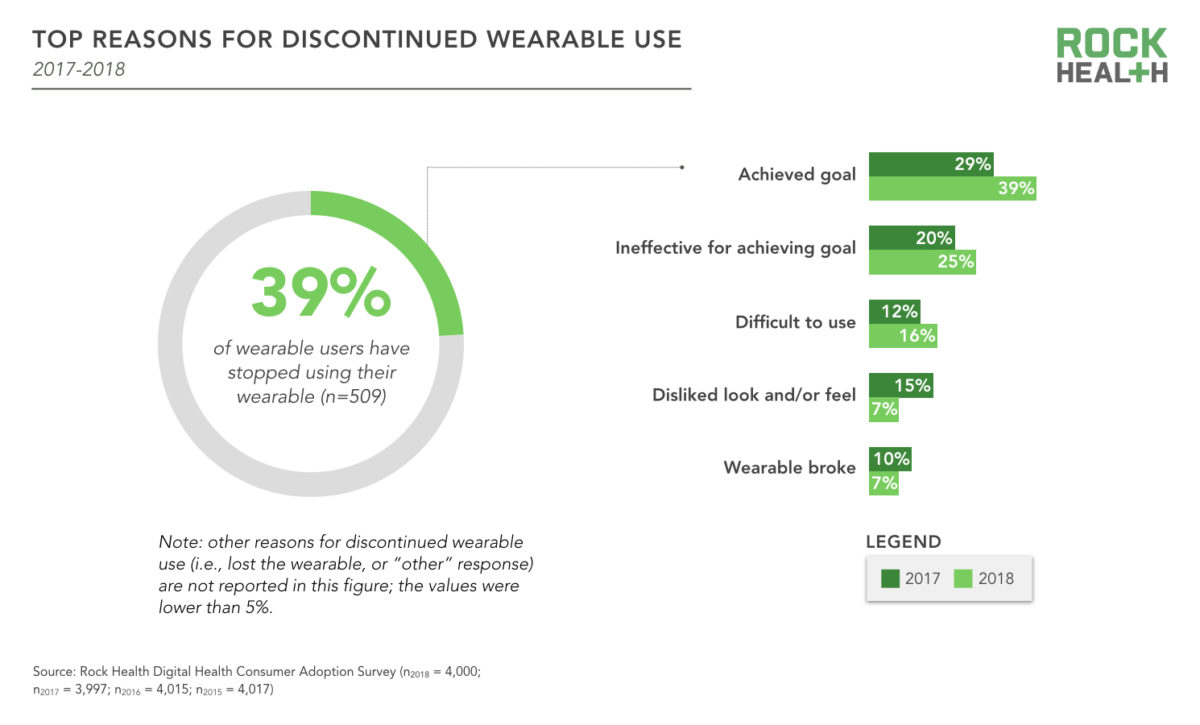

Other design features to consider are the consistency of updates and reasons for wearable device use that may not focus on physical activity. RockHealth.com (2018) digital health consumer report found monitoring fitness as the top reason for wearable use but it is down as a primary use and managing health is up 10%; other reported reasons for wearable usage were being physically active, losing weight, and improving sleep. Day & Zweig (2018) of RockHealth consumer report showed the following changes after one year:

Wearable device developer should consider reasons for discountinued use and the speed in which technology becomes ‘outdated’ which intersects with changes in fashion trends. Other factors to consider which contribute to discontinued use and act as barriers for wearable device are remembering to wear, charge, and sync to another device (more steps and equipment) (Patel, Asch, & Volpp, 2015). While wearables have a shorter shelf live do to limited ability to adapt the appearance and functionality, apps tend to have longer longevity as they can be completely revamped though software updates with one simple click.

Apps for use!

Two types of apps, educational and motivational, are most commonly used for adult focused apps but people may need multiple apps to initiate and maintain behavior change (Conroy, Yang, & Maher, 2014). Approximately “one in five smartphone users utilize at least one software application (app) to support their health-related goals” (Fox & Duggan 2010). The most successful seem to have not only educational and entertainment value, but integrated software that allows for engagement with peers.

Playing off the zombie scifi boom in popculture comes Zombies,Run! which integrates an immersive running game and audio adventure for iPhone and Android, created by Six to Start and award-winning novelist Naomi Alderman.

The app features Walk, Jog or Run Anywhere with integrated “A World Of Stories“: With 200+ missions to date, and 40 all-new episodes coming in Season 4, players can enjoy a new story every run. Additional features, such as the Zombie Chases which simulate a incoming horde, requiring players to increase their speed to escape, is yet another example of adaptability to keep users engaged and returning over time.

Section 2: Prevention and Health Promotion

In order to positively impact health and align with the all encompassing influence of technology, BCTs have become integrated in the design of health technology, such as apps and wearable devices monitoring platforms. Many apps were created for individual users but have become popular within various levels of health education and healthcare in general to improve patient outcomes. Section 2 focuses more on health related outcomes.

Multifaceted Health Promotion App

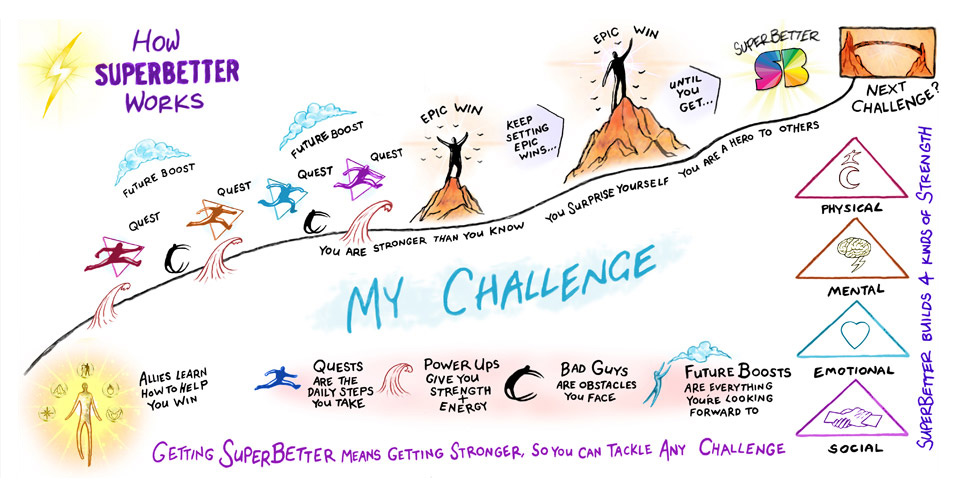

One app that has continued to outlast other health promotion apps while building on it’s initial premise is SuperBetter (www.superbetter.com). Not only does the app contain a design supported by the highest value of health behavior theories integrated into the design (n=76) (Payne, Moxley, & McDonald, 2015) but it also has continued to be validated by clinical trials for mental health and post concussive symptoms improvements.

The creator of the app, Jane McGonigal, has a fascinating personal story of struggling from a concussion which prompted her to design a game to facilitate her recovery which morphed into a multifaceted resilience training based app that is helping millions of people achieve healthy lifestyles.

Apps for Children, Teens, and Families

Kurbo is a mobile health coaching app designed specifically for kids, teens, adults and families. According to the website, 90% of Kurbo participants experience weight loss within three months, which is the focus as research shows that 80% of overweight kids remain overweight as they enter adulthood, which increases their risk for developing chronic conditions.

https://sway.office.com/fEulmntJ7Cb4RKr5?ref=Link&loc=play

Although engagement is key regarding use of BCTs within apps and wearables, the use must also be accurate within the design. Lyons et al. (2014) suggest developers to focus on appropriate integration of feedback, goal setting, and self-monitoring BCTs; recommendations include improving specificity, clarifying performance, accurate comparison to user data, scaffolding of goals, moderate challenge level, frequency of monitoring, and focus on modifiable behaviors. Many of these behaviors are included in most apps but only Kurbo included additional engagement with the incorporation of personalized coaching support to ensure some components that otherwise would be difficult from an pre-coded app.

Conclusion

Ultimately engagement of the user through BCT is most impactful for changing behaviors through apps and wearable devices; frequent strategies include combinations of motivation and encouragement, social competition and sharing, and effective feedback loops (Patel, Asch, & Volpp, 2015). When considering sedentary behaviors, video gaming often get blamed as the primary culprit along with long periods of sitting during tv watching (Tremblay et al., 2011). More studies should focus on Nintendo Wii™, Microsoft Kinect™, Sony’s Playstation Move™, video arcades, etc.) (Tremblay et al., 2011) because most top ranked apps focused on educational or entertainment BCTs (Conroy, Yang, & Maher, 2014) but ‘active gaming’ may combine both. Most apps include the necessary features of activity tracking (measuring and monitoring, information and analysis, and support and feedback), but adaptability is often lacking (Mollee et al., 2017). Even if BCTs are included in the design and integrated in a way to make use effective, other factors must be considered by designers to create a successful app. Mercer et al. (2016) suggest the following considerations: the users primary purpose of use, the starting fitness or health status of the user, and the technology literacy level of the user. Even a skillfully designed operating system that is streamlined with multiple functions grounded in BCT will not be useful if it is not user focused and specific to its target audience. There still remains a lot of room for development to educate users on functions, enhance ease of use, and create engaging media that people can use long term to promote and achieve.

References

Bliss, K., Zarco, E., Trovato, M., & Miller, A. (2018). SOCIAL MEDIA USE AMONG HEALTH EDUCATION SPECIALISTS: A PILOT STUDY. American Journal of Health Studies, 33(3).

Conroy, D. E., Yang, C. H., & Maher, J. P. (2014). Behavior change techniques in top-ranked mobile apps for physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 46(6), 649-652.

Day, S & Zweig, M. Beyond Wellness For the Healthy: Digital Health Consumer Adoption 2018. RockHealth website. https://rockhealth.com/reports/beyond-wellness-for-the-healthy-digital-health-consumer-adoption-2018/.

Fox, S., & Duggan, M. (2010). Mobile health 2010. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project.

Higgins, J. P. (2016). Smartphone applications for patients’ health and fitness. The American journal of medicine, 129(1), 11-19.

Kinsey, A. W., Whipple, M., Reid, L., & Affuso, O. (2017). Formative Assessment: Design of a Web-Connected Sedentary Behavior Intervention for Females. Journal of Medical Internet Research human factors, 4(4), e28.

Lang, J. J., Tremblay M. S., Léger L., et al. (2018). International variability in 20 m shuttle run performance in children and youth: who are the fittest from a 50-country comparison? A systematic literature review with pooling of aggregate results. Br J Sports Med, 52(4), 276-288.

Leech, R. M., McNaughton, S. A., & Timperio, A. (2014). The clustering of diet, physical activity and sedentary behavior in children and adolescents: a review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 11(1), 4.

Lyons, E. J., Lewis, Z. H., Mayrsohn, B. G., & Rowland, J. L. (2014). Behavior change techniques implemented in electronic lifestyle activity monitors: a systematic content analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(8), e192.

Mercer, K., Li, M., Giangregorio, L., Burns, C., & Grindrod, K. (2016). Behavior change techniques present in wearable activity trackers: a critical analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research mHealth and uHealth, 4(2), e40.

Mollee, J. S., Middelweerd, A., Kurvers, R. L., & Klein, M. C. (2017). What technological features are used in smartphone apps that promote physical activity? A review and content analysis. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 21(4), 633-643.

Patel, M. S., Asch, D. A., & Volpp, K. G. (2015). Wearable devices as facilitators, not drivers, of health behavior change. Jama, 313(5), 459-460.

Payne, H. E., Moxley, V. B., & MacDonald, E. (2015). Health Behavior Theory in Physical Activity Game Apps: A Content Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research serious games, 3(2), e4. doi:10.2196/games.4187

Piercy, K. L., Troiano, R. P., Ballard, R. M., Carlson, S. A., Fulton, J. E., Galuska, D. A., … & Olson, R. D. (2018). The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA, 320(19), 2020-2028.

Ruiz, J. R., Castro-Piñero, J., Artero, E. G., Ortega, F. B., Sjöström, M., Suni, J., & Castillo, M. J. (2009). Predictive validity of health-related fitness in youth: a systematic review. British journal of sports medicine, 43(12), 909-923.

Ritterband, L. M., Thorndike, F. P., Cox, D. J., Kovatchev, B. P., & Gonder-Frederick, L. A. (2009). A behavior change model for internet interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 38(1), 18-27.

Schoeppe, S., Alley, S., Rebar, A. L., Hayman, M., Bray, N. A., Van Lippevelde, W., … & Vandelanotte, C. (2017). Apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour in children and adolescents: a review of quality, features and behaviour change techniques. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 83.

Tremblay, M. S., LeBlanc, A. G., Kho, M. E., Saunders, T. J., Larouche, R., Colley, R. C., … & Gorber, S. C. (2011). Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 8(1), 98.

Yang, C. H., Maher, J. P., & Conroy, D. E. (2015). Implementation of behavior change techniques in mobile applications for physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 48(4), 452-455.