6-Evaluating Sources

3. Evaluating for Credibility

Once you have determined that a source is relevant and current, it’s very important to evaluate it for credibility. That is, should you be able to trust that source?

The best practices for evaluating credibility have recently changed in interesting ways. Previously, we looked deeper and deeper into the source itself to evaluate it. That was sort of a “vertical” look at the source. But because of research conducted at Stanford University in 2017, now we recommend you instead look at what others have written about your source. Look across other sources at what they have to say about the source you are evaluating so that you are not just accepting what sources say about themselves. This method is called “lateral reading,” and we will show you how to do it below.

To sum up right now, if you have not considered what others have written about your source and its author and publisher, you have not evaluated its credibility.

The new recommendations stem from a 2017 Stanford University study that compared university students’ and faculty members’ actions to evaluate sources with those of professional fact-checkers. The fact-checkers’ actions were superior and faster, the study concluded. You can read about the study yourself at Lateral Reading: Reading Less and Learning more When Evaluating Digital Information.

How to Use Lateral Reading+

Here’s what we recommend for evaluating credibility of the relevant sources you have found.

The goal is to end up with a list of trustworthy sources. It’s from that list you will choose some to answer your research question in your final product and meet the rest of your information needs as you complete your final product. (You can read about your information needs in Chapter 3, What Sources to Use When.)

You will get very fast at this, the more you do it. Remember, you are only checking the credibility of these sources, not whether you will use them. You’ll end up identifying trustworthy sources you can safely use, not with a list you will use. (Help for figuring out which you will use is in Chapter 10, Writing Tips.)

Your mental attitude should be one of skepticism—make the sources prove to you that they are credible.

Steps for Lateral Reading+

As you take the steps below, keep brief notes on what you find out from Steps 1-5 so that you build a context with which to infer in Step 6 that the source is credible or not credible. (We give you the details about particular steps after this list of steps.)

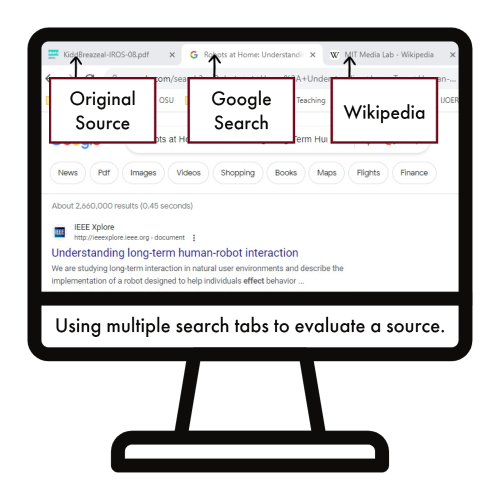

- Bring up the relevant source on your screen. (If you are evaluating a relevant print source, have it in front of you.) As you’ll see below, you will be reading or viewing one aspect of this source at a time and checking those things out online.

- Open a new tab to evaluate the source as a whole. You can look on our suggested sites that may be helpful to quickly weed out individual sources that are untrustworthy. Make brief notes on what you find out.

- Open a new tab to determine what type of source it is. This is important because different kinds of sources usually have more or fewer processes in place to ensure credibility, which is a big clue to whether you can trust them. (To review kinds of sources, see Chapter 2, Types of Sources.) Make brief notes on what you find out.

- Open a new tab to evaluate whether there is reason to believe the author and/or publisher know what they are talking about. Or do they just have opinions? Make brief notes on what you find out.

- Open a new tab to evaluate major bits of information the source puts forward as fact. Make brief notes on what you find out.

- Make your inference about the source’s credibility by grading on credibility and record it in your notes: Give it an A (very acceptable), B (good, but could be better), C (OK in a pinch), D (marginal), or E (unacceptable). You may decide to use those sources that received a C or higher grade, although you should obviously prefer those with grades A or B, especially for answering your research question.

- Go on to the next relevant source you want to evaluate.

Do you notice how almost all of your time is spent looking outside the source itself during those steps? That’s lateral reading. The idea is to not spend much time reading a source that may not turn out to be credible.

TIP:

What you should ignore online when determining credibility:

- Whether it’s a .com, .org, .edu, or .net. (It is a myth that domains of a URL indicate anything about credibility.)

- Whether it looks aesthetically pleasing.

- Whether the site has advertisements.

- Whether scientific jargon or statistics are used.

- How socially approved a website’s or its organization’s name is.

Details about Step 2

You’ll want to find out what others have thought of your source as a whole. Open a new tab and use Google or Bing to type in the name of the website, the publisher, and/or the author of the source. View some of your initial results.

Has anyone raised concerns about your source? If so, look for assessments of your source on a few of these websites: Wikipedia, NPR, Snopes, Politifact, SciCheck, FactCheck.org, and Washington Post Fact Checker. Wikipedia also has a list of fact-checking websites about political and not-political subjects.

What they found out may make you immediately distrust the source and rule it out. But their reviews of your source—or lack of a review–may be positive enough to keep you evaluating it.

Next, look for other websites’ assessments of your source among your search results. Your Google results page should show you above each title where each result was published, as is illustrated here for a search for consumerism ecology and here in Google Scholar for the same search. Did others identify any problems or good things about the source? Record that in your notes.

TIPS:

Are you trying to see what others are saying about a journal article? There are tools that track where journal articles (and some conference papers and books) are being cited. Scopus and Web of Science are two library databases that do this. Google Scholar also does this, as well. A few cautions:

- New content hasn’t had a chance to get cited.

- Some subject areas may make use of certain formats more than other subjects (books may get more citations in math than in physics, for example).

- Citing something doesn’t equal agreeing with it.

- Different subject areas have different citation levels. Areas like medicine or physics articles tend to get more citations than history or literature articles, for example.

- Some journals’ items get cited more because of their reputation, but that doesn’t mean other titles have bad content.

Details about Step 3

This step accounts for the “+” in “Lateral Reading +”. Here’s where you determine which type of source you’re evaluating, which involves thinking about who it was created for. If you get stuck, thinking about what the source’s purpose is can help.

Figure out who it was created for. Ask yourself whether it is (a) a popular source for everyone, (b) a substantive popular source created for educated people or those very interested in the subject, (c) a professional source created for members of a particular profession, or (d) a scholarly source aimed at scholars and others who want a deep view of a subject. (If you need to brush up on these distinctions, see Chapter 2, Types of Sources.)

You can often get fast clues to what kind of source it is even before clicking on it on your results page in Google or Bing. For instance, the URL may tell you the source was published in an online version of a newspaper or magazine.

Or maybe you searched for the source in Google Scholar or a library database, so you already know that your source is likely to be a professional source or a scholarly article in a research journal. For more on how to tell what each database covers (often called its scope), see Chapter 5, Search Tools. (If you are in a life sciences course, make sure to ask your professor whether Google Scholar is a good search engine for you.)

Wikipedia can sometimes tell you whether your source is a magazine, newspaper, journal, etc. For instance, see what Wikipedia says about Men’s Health, Investopedia, and Cell. Library catalogs can also tell you about sources, as these OSU Libraries full catalog entries do about Athletic Business and The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes.

In general, substantive popular sources, professional sources, and scholarly sources tend to be more credible than popular sources. That’s because the creation of these kinds of sources often involves processes that help ensure their accuracy. (You still need to evaluate them, but it tends to be easier.)

Those processes include ways of preventing inaccuracies (including fact checkers for many substantive popular sources and peer review for scholarly sources) and ways of correcting mistakes that nonetheless occur. For instance, major U.S. newspapers correct previously published information every day or week and research journals retract journal articles whose inaccuracies becomes apparent. Even articles by Nobel laureates have been retracted, as this article in the journal Nature illustrates.

Because their processes are so strong, The New York Times and The Washington Post are considered to be newspapers of record. Other news sources such as the Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, Los Angeles Times, Star Tribune in Minnesota, NPR, PBS, ABC News, CBS News, NBC News, the Associated Press and Bloomberg wire services, and the BBC are also substantive popular sources with strong processes for credibility.

The same is true for magazines such as The Atlantic, The New Yorker, Harpers, National Review, Discover, Popular Science, Popular Mechanics, Psychology Today, Wired, Forbes, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Smithsonian, FiveThirty Eight, National Geographic, and Slate. TED is also a substantive popular source.

That doesn’t mean they and the many, many other credible substantive popular sources never make mistakes. But it means that those like the ones named take special care to be more credible than popular sources in general.

Here’s an essay called “Journalism’s Essential Value” by the publisher of the New York Times about the importance of news sources remaining an independent source of information, unlike many newspapers in Europe (such as the Guardian and the Guardian U.S., which lean left politically) and what some would want here in the U.S. The essay was published in the Columbia Journalism Review (a professional source) on May 15, 2023.

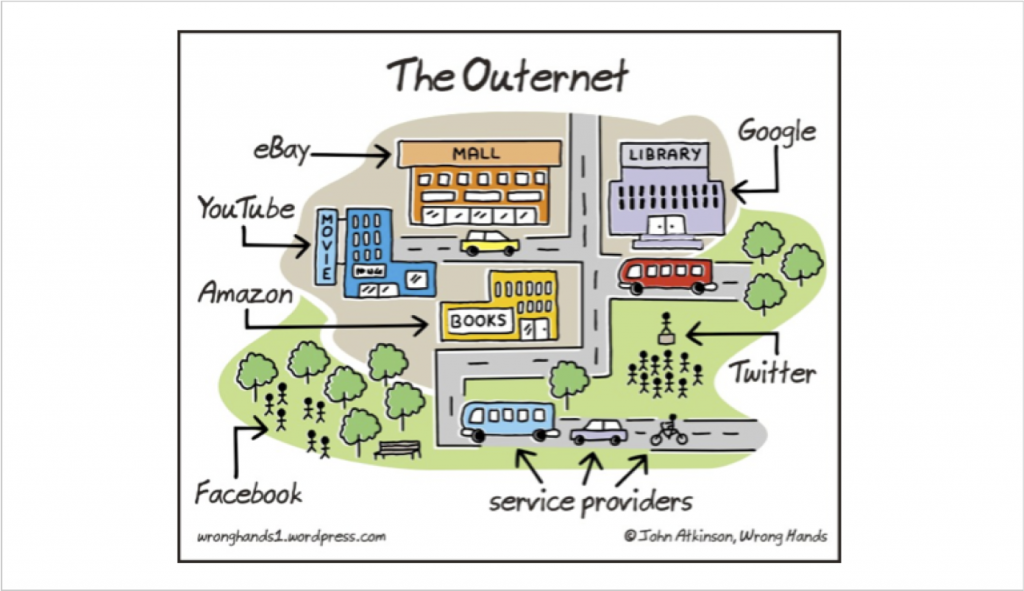

If, after considering who the source was created for, you are still unsure of an online source’s type, determining the source’s purpose can help. To do so, consider what Internet neighborhood the source is published in.

To understand this concept and begin to use it, imagine that all the sites on the web constitute a community. Just like in a geographical community, there are neighborhoods in which individual sites hang out.

Self Check

Under what condition would it be permissible to use a source that is obviously biased because it is from an advocacy group? (See the answer at the bottom of the page.)

Audio: Neighborhoods on the Web

Listen to the audio clip (or read the text version) to hear how intuitive this concept is. After you listen or read, the next activity will show you how to apply the concept.

Listen to Audio | View Text Version

Start making short notes of the clues you found to start building a context for your eventual decision to trust or not trust the source.

ACTIVITY—What Kinds of Sources?

Here’s a chance to start evaluating for credibility yourself. To find out what kind of sources are in the questions below, look at each source but then use lateral reading to look outside the source itself.

Source Links:

- Scientific American

- The Economist

- Web of Science

- Birds of a Feather Video-Flock Together: Design and Evaluation of an Agency-Based Parrot-to-Parrot Videos-Calling System for Interspecies Ethical Enrichment

- Nude Descending a Staircase by Marcel Duchamp

- Editor and Publisher

- Braiding Sweetgrass by Dr. Robin Kimmerer

- Science Friday podcast

- “Efficient Evolution of Human Antibodies from General Protein Language Models”

Details about Step 4

Now go back to your source and open up a new tab. This time you will be identifying who created and published your source and whether you think they are trustworthy about the information in this source.

As you consider what you learn about the author and/or publisher, ask yourself whether any of your results give you a reason to suspect they are interested in providing misinformation, perhaps for profit or for religious or political reasons.

If so, that doesn’t necessarily make it an unacceptable source, depending on your research question. But you should be aware of that potential bias of the source because it’s part of the context of the conversation around that source.

In addition, if you end up using and citing such a source, you may want to couch your language about it in your final product, as in “These authors say X about Y, although one has to keep in mind what might be their political bias.” That way, your instructor will know that you are aware of the whole conversation so far about this source, which always counts as a positive. (See our feedback about the sources in our last activity in this chapter called Your Turn to Evaluate for more on this subject.)

The more you know about the author and/or publisher, the more confidence you can have in your decision about credibility. Sites that do not identify an author or publisher are generally considered less credible for many purposes, including for research papers and other high-stakes projects. The same is true for sources in other formats, including videos and print.

Authors and publishers can be individuals, organizations, companies, or government agencies. (Webmasters put things on the site but do not usually decide what goes on all but the smallest websites. They often just carry out others’ decisions.)

If your source is online, you may see a hyperlinked author name. Click on that to see if you can get more information about the person. Sometimes, you may see information about them at the bottom of the source. If it’s a scholarly journal, book, or conference paper that you are examining, you will often see their affiliation (where they work) – often a university, research lab, museum, or some other institution with experts. Databases like Scopus and Web of Science also allow you to look up authors and see profiles of their research (just be careful to get the right person – some names are very common!).

You may find the publisher’s name next to the copyright symbol, ©, at the bottom of at least some pages on a site. In books, the identity of the publisher is traditionally on the back of the title page, with a few sentences about the author on the back cover or on the flap inside the back cover. (But, of course, remember that those comments are those the publisher decided to publish.)

If your source is a website, sometimes it helps to look at the source’s URL for whether it belongs to a single person or to a reputable organization. Because many colleges and universities offer blog space to their faculty, staff, and students that uses the university’s web domain, this evaluation can require deeper analysis than just looking at the address. Personal blogs may not reflect the official views of an organization or meet the standards of formal publication.

Unless you find information about the author to the contrary, such blogs and websites should not automatically be considered to have as much authority as content that is officially part of the university’s site. But you may instead find that the author has a good academic reputation and is using their blog or website to share resources he or she authored and even published elsewhere. That would nudge him or her toward the school’s neighborhood of the Intranet and toward credibility.

In this step, you are trying to figure out whether the author and/or publisher publishes serious information and has a “good” reputation. Is there reason to believe that the author knows what he or she is talking about? This involves considering what they have published before and where, where they work, and their academic and other credentials.

Don’t be automatically impressed with Ph.D. or M.D. degrees. A Ph.D., M.D., or other advanced degree is not automatically a marker of someone you can trust about the information in your source.

Ask yourself whether their academic degree makes sense with the subject matter they are writing about. Someone with a Ph.D. in chemistry, for instance, may not know anything about criminology and whether sentencing guidelines should be changed for Americans convicted of a crime.

College credentials are not the only thing that could matter. Maybe an author has substantial life experience or training that seems sufficient to make them authorities on the subject of your research question. For that reason, for example, a comparatively uneducated person who has lived for many years in a rural county may be able to provide you with information about what that’s like that is just as credible as what a university professor of rural sociology can provide.

ACTIVITY: Checking the Authors and/or Publishers

Check out the author and/or publisher of these sources on the web and select things you notice about them that you think should be considered in your decision about the credibility of each. Some answer options are not true, so don’t assume an answer option is true until you verify it.

Source Links:

- Outsmart Your Brain: Why Learning is Hard and How You Can Make It Easy, by Daniel T. Willingham, Ph.D. Gallery Books, 2023.

- “What to Know about Romance Scams”

- “The Illusion of Moral Decline.” Mastroianni, A.M., Gilbert, D.T. The illusion of moral decline. Nature (2023). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06137-x#author-information

Looking for what else the author has written can include searching a large library catalog (OSU Library Catalog, OhioLINK, WorldCat@OSU).

If your source is an article, you might also look in Google Scholar. (While you can search for free, you may not be able to retrieve articles unless searching through a library.) Specialized library databases that cover the same topical area as information on a website can also be helpful (and free). For example, use the database ERIC (OSU users only) to locate any articles published by the author on an education website. Scopus and Web of Science are other good examples where you can look. OSU Libraries databases, arranged by subject or guides.osu.edu can also direct your search for information about an author or publisher.

Record whether you consider the author and/or publisher trustworthy in your notes and why or why not.

TIP:

What should help you trust?

- Determining that the source is a substantive popular source, a professional source, or a scholarly source.

- Seeing that other sources you respect trust it.

- Its author/publisher seems expert.

- Its author/publisher seems uninterested in providing misinformation for profit or for religious or political reasons.

Details about Step 5

Go back to your source and start reading or viewing it, engaging in the argument the author is trying to make. Identify major statements of fact the author makes and then check a few of them out on Google, Bing, or any of the search tools or databases and other links listed in Step 4. Keep track of what others have said about your source’s statements of fact so that you get an idea of how well their ideas are accepted by others.

Remember, though, that if your source is especially innovative, not everyone may agree with some of its statements of fact and it could still be a credible source. You’ll have to use your own critical thinking skills about the topic and your research question as you consider your course’s credibility here.

For example, this New York Times story covers how long and hard two Australian medical researchers had to work to convince other doctors that a bacterium, rather than stress, causes most stomach ulcers—one even infected himself with the bacterium so as to cure the resulting ulcer with a drug. In the story, a former dean of the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Medicine states that peer review “tends to adhere to things that are consistent with prevailing beliefs and models,” and “really new ideas usually just get thought of as crazy.”

That fits with the fact that the Australian researchers identified the bacterial cause of ulcers in 1979, but it wasn’t until 2005 that they received a Nobel Prize for the importance of that discovery and their persistence in convincing other doctors.

A note about data:

You can use the same skills to evaluate text for credibility to evaluate data. Use the 5Ws and 1H questions to ask yourself:

- Who created or owns the data? A non-profit or government organization? A corporation? A lobbyist? Does the individual or organization who created or owns the data have an incentive to collect or present the data in a particular way to support its mission?

- What variables were collected and how are these variables defined?

- Where did the data originate? If survey data, are the survey demographics relevant for your project? If scientific data, is the material or population sampled relevant for your project?

- When was the data first created or last updated?

- Why is the data important to you? Will it support your argument? Help you make a decision?

- How was the data created? What was the methodology used to collect the data? Was the methodology valid?

Data is influenced by the individuals who design and implement the processes used to collect it. Consider the influence of bias when evaluating both raw and reported data.

ACTIVITY: Your Turn to Evaluate

Use lateral reading to evaluate which of these organizations is more credible. (These sites were used in the 2017 Stanford study cited in Chapter 6.)

After Making Your Inferences in Step 6

Success! After evaluating for credibility and making your inferences, you should have a group of sources that you feel confident are not just relevant and current or in the right time period but that are also ones you can trust.