Chapter 10 – Musica Insecta

One of the best things about being human is that we’ve cultivated the use of sound to the status of high art. We speak, of course, about music, which is tied to human society and culture so deeply and so intimately that we’ve come to feel that humans have actually invented it. That may not be true as we have learned in Chapter 9, because insects were producing sounds long before humans existed. But, it is true that humans have been incredibly inventive in molding sound to suit diverse ends, enabling us to use music to evoke a variety of moods from patriotic fervor to terror to intensely emotional and beautiful pieces that generate a sense of deep pleasure and satisfaction in the part of the brain called the amygdala. We’ve even devoted considerable effort towards understanding how music impacts human physiology in an attempt to glean the source of music’s strange power. In short, music is at once mysterious and magical. And even if individuals possess little in the way of musical talent, most humans will be actively involved in both the production of and listening to music throughout their lives, which speaks to the power of music.

Insects as Muses

Our task here is to investigate whether insect sounds or insect-based motifs are used in the production of human music. In other words, did insects serve as muses for humans attempting to express themselves in the art form we call music? As we’ve seen in previous chapters, insects were not far from the human imagination when we were looking for exemplars in myth or religious texts. It, therefore, makes sense to ask if so important and so universal a phenomenon as music has also been used a vehicle for having insects make specific points or to create particular moods? The unsurprising answer is, emphatically, yes! The representations of insects in music are many and varied. In Chapter 9 we focused on the insects themselves as makers and singers of music. Now, we will focus on music written about insects or in which insect motifs are used.

To get things started, please read the following poem by Emily Dickinson which represents, perhaps, a kind of insect-based music whose original intention was something else. The poem was meant by Dickinson to pay homage to the venerable insect known as the cricket. From time to time, poems such as this are set to music and are, thus, legitimate representatives of insects in music.

My Cricket

Farther in summer than the birds,

Pathetic from the grass,

A minor nation celebrates

Its unobtrusive mass.

No ordinance is seen,

So gradual the grace,

A pensive custom it becomes,

Enlarging loneliness.

Antiquest felt at noon

When August, burning low,

Calls forth this spectral canticle,

Repose to typify.

Remit as yet no grace,

No furrow on the glow,

Yet a druidic difference

Enhances nature now.

—Emily Dickinson

The archaic language of the poem requires a little explanation. The second line, “Pathetic from the grass,” for instance, uses the word “pathetic” not as an insult, but to convey the idea that the crickets are small in size and would hardly be noticeable at all if not for the sheer number and the determined chirping of the males. The third stanza uses the word “antiquest” which is a superlative form of the word antique. Dickinson uses this rather unfamiliar word to suggest great age.

The words of the poem convey a sense that a welcome summer ritual has arrived, with dependable punctuality, and has set in motion an ancient rite. The appearance of the crickets and their song reminds Dickinson of our place in nature. Set to music, the emotional impact of the words is accentuated, giving the hearer not just a means of hearing and evaluating the words, but of reaching into the nervous system and using the power of music to carry the message to the heart as well as brain. We might not normally find crickets to be a source of emotional gratification, but set to music, the Dickinson poem can have this effect.

As we’ve suggested, insects are regularly found as topics, not only in music that is performed, but in the names adopted by the performers (take for example the “Beatles” which were inspired by another musical group “Buddy Holly and The Crickets”). There’s just something about insects that either aesthetically or, perhaps, biologically makes them fascinating to humans involved in music-making or music-listening. In order to make sense of this, however, we need to start with the basics by asking the simple question what is music?

Is wind blowing through the trees music?

Is a car backfiring music?

What about the sounds made by appliances in your kitchen?

Are any of these music?

Outside truly avant garde music, probably not. A more standard, although not necessary complete definition, would be something like: music is the art and science of combining sounds or tones in varying melodies, harmonies, and rhythms so as to form complete and emotionally expressive compositions.

A simpler definition is that music is any rhythmic sequence of pleasing sounds. Whichever definition you choose, please note that for humans music involves the brain, which processes the sound and gives it meaning. Our goal is simply to study and understand the relationship between insects and music.

It is, perhaps, not surprising that the representation of insects in music has many similarities to the use of insects in myth and divine texts. This, of course, reflects the fact that insects are common in the everyday lives of people in all societies, often in ways that are not positive. Insects are habitually on peoples’ minds and when they need a topic with emotional content, insects are there right near the surface. Also, since many insects can produce sound, this naturally recommends insects for a place in musical compositions.

As with myth and religion, we find a variety of uses for insects in music ranging from literal (or onomatopoetic) to metaphorical/allegorical to humor and satire. Often a life habit of the insect is called out to make a particular point suggesting a well-developed understanding of insect biology among musicians and composers.

Insects in Classical Music

Insects are routinely found in classical music compositions. As with myth and religion, the allusions to insects in classical music are so numerous that it helps to break them into taxonomic groups. Butterflies, for instance, are used liberally by classical composers, often appearing in the title of the piece. From instrumental pieces to opera, butterflies have been used to convey emotion and beauty in musical compositions. Often, the metamorphic capacity of insects is used to drive the musical theme, using metamorphosis as a metaphor for rebirth or the emergence of beauty from ugliness. French composers seem to have a particular fondness for butterflies, which have been used to good effect in compositions written by Faure, Couperin, and Offenbach, who was German-born but given French citizenship by Napoleon. All of these composers have a piece entitled “Le Papillion”— or “The Butterfly” translated into English.

Of course, no discussion of butterflies in classical music would be complete without mentioning the iconic opera “Madame Butterfly” by Giacomo Puccini. The opera was developed from a short story written by the American, John Luther Long, which piqued the interest of playwright, David Belasco. Working with Long, Belasco developed the story into a one-act play. The composer, Giacomo Puccini saw the play and was intrigued, prompting him to convert Long’s story into an opera, which debuted at La Scala in 1904.

The storyline is complicated but basically presents the story of Cho-Cho-Son, a Japanese woman, who marries an American naval officer stationed in Japan. The naval officer, named Pinkerton, marries Cho-Cho-San basically as a convenience— and in a first of many questionable acts, refuses to let Cho-Cho-San’s family visit. This causes her family to disown her. Shortly thereafter, Pinkerton leaves Japan, at which point, Cho-Cho-San is pregnant with his child. Cho-Cho-San continues to believe that Pinkerton will return to her but, sadly, when he does physically return to Japan, he is in the company of a new American wife who is determined to adopt Cho-Cho-San’s child. And so, the lead character meets a tragic end as a result of her philandering husband’s treachery.

Many themes are explored in the opera. Among them, the characteristics of different cultures as well as gender roles and the damage that rigid adherence to cultural mores can have. The butterfly motif becomes metaphor in a couple of ways. First, one sees the transformation of Cho-Cho-San as the opera progresses, in which she is changed from a hopeful, beautiful young woman into the scorned wife whose abusive husband pays very little for repeated acts of deliberate cruelty. Second, despite the cruelty, Cho-Cho-San is drawn to the loathsome Pinkerton as a moth is to a flame. In the end, Cho-Cho-San is redeemed by an act of self-sacrifice that saves her child—much as the beautiful adult butterfly must die so that the young can arise to continue the species.

Another popular theme in classical music is the fly. Unlike divine texts, not every reference to flies in classical music is negative. For instance, consider Bela Bartok’s “Diary of a Fly” from Mikrokosmos an amalgamation of 153 pieces for piano in 6 volumes. “The Diary of the Fly” is a literal representation in which Bartok mimics the sound of a fly caught in a cobweb from the fly’s perspective, which is recorded in his diary. A buzzing sound starts the piece as the bound and terrified fly attempts to escape from the web. The opening buzzing sound is a theme that ascends the keyboard, then gradually grows louder, more distinctive and intense. It is meant to evoke a sense of fear and impending doom. Then, the fly escapes and the music mood shifts from the frenetic activity of prey trying to escape, into tranquility. It’s only a minute long, so please listen by following the link to YouTube (Video 10.1).

Another deeply despised insect, the flea, also appears with surprising frequency in classical music. Even more surprising, a large number of composers have written independent compositions entitled “Song of the Flea” or have appropriated and revised the work of others with this title. Who knew that fleas were so popular?

The flea-based classical music actually originated with Hector Berlioz, who wrote the flea song in 1845 as part of his operatic setting of “The Damnation of Faust” (inspired by his reading of Goethe’s “Faust Part One”). Berlioz tells the tale of Faust, who shortly after reaffirming his love for life is confronted by Méphistophélès (representing Satan). Faust is tempted by Méphistophélès, who offers worldly gains if Faust will follow him out into the world. Although Faust is mistrustful at first, he agrees to follow his dark companion. The first stop is a beer cellar in Leipzig where Faust takes an immediate dislike to the loutish singing of inebriated students. The students belt out Brander’s Song of the Rat with a sacrilegious “amen” thrown in for good measure at the end. This disgusts Faust, who then leaves the bar. The students, meanwhile, challenge Méphistophélès to best their song and he replies to the student challenge with his “Song of the Flea”—a story told about a flea who takes up residence in the royal palace. The flea wears clothes of fine velvet and infests all of the humans who come to court. The Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky heard “Damnation of Faust” in St. Petersberg and was inspired to compose his own version of “Song of the Flea,” which became one of Mussorgsky’s most well-known songs.

Mussorgsky has an interesting history which is worth sharing. He was a child prodigy on piano and, as an adult, held a variety of positions, including a commission to serve in the Russian Imperial Guard. Mussorgsky later became a civil servant. He wrote music throughout his life, much of it recapitulating Russian folk themes. Unfortunately, Mussorgsky had a habit of overindulging in the consumption of alcohol. His music, while original, was poorly arranged and orchestrated. The music had to be “cleaned up” by others, which was primarily the Russian composer, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Rimsky-Korsakov’s name is, therefore, sometimes associated with “Song of the Flea” making Rimsky-Korsakov the third composer whose name appears with a piece called “Song of the Flea.”

As seen in Emily Dickinson’s poem, orthopterans are also a popular choice among the artistic class—including poets and classical composers. Benjamin Britten, for instance, wrote a piece for oboe entitled “The Grasshopper.” Grasshoppers also appear (although this time in Spanish as “El Grillo”) in a madrigal by des Prez, a Renaissance composer.

A translation of the lyrics show an interesting mix of biology and sentiment:

El Grillo

“The Cricket is a good singer

Who sings for a long time

The cricket sings just for fun

The cricket is a good singer

But unlike birds who

Fly off when they’ve sung a little

The cricket just stays where he is

When the weather is really hot

He sings only for love.”

—Josquin de Prez

Insects inspire the muse in some negative ways too. A variety of classical pieces acknowledge things that sting. “The Wasp” (a piece for oboe and piano by Britten) attempts to capture the fear occasioned by the wasp with its capacity to inflict bodily harm. Interestingly, “The Wasp” was published with a second insect-based piece entitled “The Grasshopper.” The phenomenon of having musicians write multiple pieces that involve insects is not uncommon.

Also in the category of hymenopteran music, we have Mendelsohn’s “Bee’s Wedding” which is a song from a larger work, “Song without Words.” And Vaughan Williams weighs in with a second piece entitled “The Wasps.” It was written as incidental music for a production of Aristophanes’ play, “The Wasps” produced at Trinity College in 1909.

But, of course, probably the most famous of all insect-inspired classical pieces is “Flight of the Bumblebee” by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. This piece appeared as an interlude in the opera, “The Tale of Tsar Saltan.” The interlude functions basically as an incidental piece that fills in as scenes are changing and singers are shuffling about. In this case, “Flight of the Bumblebee” closes Act 111, Tableau 1 in which the magic swan-bird causes Prince Gvidon Saltanovich, the Tsar’s son, to change into an insect so that the son can fly away to visit his father who thinks the son is dead.

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote a vocal line that is sung during the “flight” in the opera but it is not melodic and the words can easily be omitted so that the piece can be played as a solo instrumental or orchestral piece. The piece is renowned for its onomatopoetic reconstruction of the sound of an actual bumblebee. It is so accurate that it makes you look around for the flying bumble bee. This is the height of literal representation of insect-based sound. Click on the link provided (Video 10.2) to listen to violinist Katica Illenyi play Flight of the Bumblebee with the Gyor Philharmonic Orchestra.

In addition to signature works that are completely based on insects, hosts of classical composers use insect motifs in larger pieces like concerti and symphonies. The examples abound, but a relatively well-known one is Handel’s “Israel in Egypt.” In this piece he recounts the 10 plagues sent by Yahweh to convince the Pharaoh to let the Israelites go. Insects enter the score in a fairly literal way using tenors and basses to create a powerful unison where the declaration of God is invoked with “He spake the word.” This is followed by the voices of sopranos and altos who sing “There came all manner of flies.” Here, Handel uses a whirring sound to create a sensation of buzzing from the insects. This increases in volume as a later insect-based plague is referenced with arrival of a plague of locusts. It is very dramatic stuff, indeed.

Another well-known classical composer, Antonio Vivaldi, was also keen on using insects in his musical compositions. In his collections of concerti known as “The Four Seasons,” Vivaldi pays homage to insects explicitly in the concerto entitled “Summer.” In fact, Vivaldi was fond of writing handwritten notes on the score so that the composer’s intent was quite clear. In addition, each season is preceded with a sonnet, presumably written by the composer. “Summer” boasts a sonnet alive with life—including a variety of birds and “by the furious swarm of flies and hornets.”

Insects in Popular Music

Not surprisingly, popular music is filled with allusions to insects. It is a short distance from folklore to song, and insects are hot commodities when writing music from traditional to modern pieces. Many songs are recycled though generations. Because there are so many insect songs, it is, again, useful to separate them by taxa.

Some of the really famous songs have been rendered into several languages. “La Cucaracha,” for instance, is often sung even by American children in Spanish. And if it is sung in English, watchful parents may forbid its singing.

For in English, the lyrics inform us:

La Cucaracha

The cockroach, the cockroach

Can’t walk anymore

For it doesn’t have, because it lacks

Its two back feet

[or marijuana for smoking]

(depending on the version)

Listen to one version of La Cucuracha by following the YouTube link (Video 10.3).

Breaking into insect orders, the sucking lice (Anoplura) chime in with a couple of songs: “Crab Louse” by Aphex Twin and “Strangers in my Shorts” by Bob and Tom. Both are representations of lice that tend towards literal meaning.

Aphex Twin again comes up when we consider the Coleoptera with their piece entitled “Beetles,” the lyrics for which are given below. And they have lots of company, e.g., with the songs “Ladybug” by the Mathletes, “Glow Worm” by the Mills Brothers (see following), and several offerings of fireflies.

Beetles

Under my feet

They come out when they eat

Beetles in my carpet

Under my feet

They come out when they eat

Beetles in my carpet

Under my feet

They come out when they eat

—Aphex Twin

Glow Worm

Shine little glow-worm, glimmer, glimmer

Lead us lest too far we wander

Love’s sweet voice is callin’ yonder

Shine little glow-worm, glimmer, glimmer

Hey, there don’t get dimmer, dimmer

Light the path below, above

And lead us on to love

Glow little glow-worm, fly of fire

Glow like an incandescent wire

Glow for the female of the species

Turn on the AC and the DC

This night could use a little brightnin’

Light up you little ol’ bug of lightnin’

When you gotta glow, you gotta glow

Glow little glow-worm, glow

Glow little glow-worm, glow and glimmer

Swim through the sea of night, little swimmer

Thou aeronautical boll weevil

Illuminate yon woods primeval

See how the shadows deep and darken

You and your chick should get to sparkin’

I got a gal that I love so

Glow little glow-worm, glow

Glow little glow-worm, turn the key on

You are equipped with taillight neon

You got a cute vest-pocket *Mazda*

Which you can make both slow and faster

I don’t know who you took the shine to

Or who you’re out to make a sign to

I got a gal that I love so

—Mills Brothers

We’ve already talked about one ballad dedicated to Dictyoptera (“La Cucharacha”) but we mustn’t leave out “Cockroach” by Albert King and “Praying Mantis” by Don Dixon. Both are worthy for their length and, in the case of “Praying Mantis”, biological accuracy.

Cockroach

You’ve got me sleeping on the porch

Laying in my arms, where you ought to be

There’s a big cockroach

Looking up at me

Sleeping on this concrete porch

Ain’t no fun at all

But I’m gonna stay right here

Until I hear you call

With this big cockroach

Looking up at me

Well a big cockroach

he’s just laying there

looking up at me

I’m glad it’s in the summer cause I couldn’t make it through a winter storm without your loving arms to keep me warm

Hey a big cockroach

He’s just laying there

Looking up at me

He’s a big brown fella

I tell you he’s just laying there

Looking up at me

Get away!

Sure is tiring these cockroaches crawling all up and down my arms and on my legs

Open the door baby

Let me in!

—Albert King

Praying Mantis

You’re standing apart again Mark

One two, one two three four

I saw a girl, she reminded me of you

She did the things that a girl like you might do

Her body was green and she had two vicious jaws

She polished her mate as she kissed him with her claws

Yeah but I’ll survive, it was on TV

She had six strong legs and it frightened me

She had insect eyes but I could still see that the look she gave him you give to me

I feel like a praying mantis (I feel like a praying mantis)

I sense your antics but I can’t help it (I sense your antics but I can’t help it)

I’ve been too frantic too long (I’ve been too frantic too long)

She bit off his head so he would not feel the pain

She wanted his body so much she ate his brain

Yeah but I’ll survive, no you won’t catch me

I’ll resist the urge that is tempting me

I’ll avert my eyes, keep you off my knee

But it feels so good when you talk to me

I feel like a praying mantis (I feel like a praying mantis)

I sense your antics but I can’t help it (I sense your antics but I can’t help it)

I’ve been too frantic too long (I’ve been too frantic too long)

I feel like a praying mantis (I feel like a praying mantis)

I sense your antics but I can’t help it (I sense your antics but I can’t help it)

I’ve been too frantic too long (I’ve been too frantic too long)

Yeah but I’ll survive, it was on TV

She had six strong legs and it frightened me

She had insect eyes but I could still see that the look she gave him you give to me

I feel like a praying mantis (I feel like a praying mantis)

I sense your antics but I can’t help it (I sense your antics but I can’t help it)

I’ve been too frantic too long (I’ve been too frantic too long)

I feel like a praying mantis (I feel like a praying mantis)

I sense your antics but I can’t help it (I sense your antics but I can’t help it)

I’ve been too frantic too long (I’ve been too frantic too long)

I feel like a praying mantis (I feel like a praying mantis)

I sense your antics but I can’t help it (I sense your antics but I can’t help it)

I’ve been too frantic too long (I’ve been too frantic too long)

I feel like a praying mantis (I feel like a prey)

I sense your antics but I can’t help it

I’ve been too frantic too long

I feel like a praying mantis (I feel like a prey)

I sense your antics but I can’t help it

I’ve been too frantic too long

I feel like a prey

—Don Dixon

The Diptera are also well represented with the inimitable Eddie Van Halen who put out an instrumental version of “Spanish Fly” for guitar, which is said to require great musicianship on the part of the guitarist. Another tribute to the Diptera comes from comedian and songwriter Haywood Banks with “Fly’s Eyes,” which gives an account of what it is like to be a fly and do fly things. Finally, we have “Maggots” by Gwar which is almost too graphic and too dark—one might almost say too creepy for polite conversation.

Fly’s Eyes

I’m looking at the world through fly’s eyes

Looking at the world through fly’s eyes

Looking at the world through fly’s eyes

And you can just buzz off

Well I think I’ll buzz in the front door

Think I’ll buzz around the back door screen

Think I’ll buzz around your face

And then I’ll land on the ceiling

Well I get up in the morning when the dew is on the doo

And I date a little maggot named Mary Lou

Some day we’ll get married and we won’t think twice

When our kids all look like dancing rice

I think I’ll land on some horse manure

Think I’ll land on the poop du jour

Think I’ll land on a squashed possum

And then I’ll land on your potato salad

(Just washing up!)

Buzz buzz buzz buzz buzz buzz…

I’m looking at the world through fly’s eyes

Looking at the world through fly’s eyes

Looking at the world through fly’s eyes

And you can just buzz off

Get that fly, get that fly!

(Accordian solo)

I’m looking at the world through fly’s eyes

Looking at the world through fly’s eyes

Looking at the world through fly’s eyes

And you can just buzz, you can just buzz, you can just buzz off!

—Heywood Banks

Maggots

Vile form of Necros lies rotting in your mind

Feasting like maggots, maggots in flesh

So you left your ruined cortex behind

Now the maggot knows glee as it nibbles on your spine

Maggots, maggots

Maggots are falling like rain

Maggots, maggots

Maggots are falling, falling like rain

Putrid pus-pools vomit blubonic plague

Bowels of the beast reek of puke

How to describe such vileness on the page

World maggot waits for the end of the age

Maggots, maggots

Maggots are falling like rain

Maggots, maggots

Maggots are falling, falling like rain

Like rain

Beneath the sky of maggots I walked

Until those maggots began to drop

I gaped at God to receive my gift

Bathed in maggots till the planet shift

The maggots are falling like rain

The maggots are falling like rain

Now in the halls of the necro-lord

Flash of fear when he sees my sword

I rape his woman, smoke his bong

Leave a little booger underneath his throne

The maggots are falling like rain

The maggots are falling like rain

Maggots, maggots

Maggots, maggots

Maggots, maggots

Maggots, maggots

Maggots are falling like rain

Maggots, maggots

Maggots are falling like rain

Maggots, maggots

Maggots, maggots

Maggots, maggots

Maggots are falling, falling like rain

—Gwar

To redeem the Diptera, let’s end this part of the review with a song which may be part of childhood memory. At summer camps across the nation, the song “Blue-tailed Fly” or “Jimmie Crack Corn” is a common feature when campers gather around the campfire for a song fest. When the title “Blue-tailed Fly” is used, the children will have a sense that this is about an insect. But who among us at the tender age of the typical camper will know that this is actually a song of protest. And the thing being protested is slavery. Yes, the humble fly was enlisted in early fights to end racial injustice. Who knows? Maybe it will be again!

Because it originated as a folk song, various versions (lyrics) and authors have been cited. However, the most common version today is often credited to the Virginia Minstrels.

Blue-tailed Fly

When I was young, I used to wait

On the boss and give him his plate

And pass him the bottle when he got dry

And brush away the blue tail fly

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

My master’s gone away

And when he would ride in the afternoon

I’d follow after, with a hickory broom

The pony being rather shy

When bitten by blue tail fly

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

My master’s gone away

One day, he ride around the farm

The flies so numerous, they did swarm

One chanced to bite him on the thigh

The devil take the blue tail fly

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

My master’s gone away

The pony run, he jumped, he pitch

He threw my master in the ditch

He died and the jury wondered why

The verdict was the blue tail fly

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

My master’s gone away

They lay him under a ‘simmon tree

His epitaph is there to see

“Beneath this stone, I’m forced to lie

Victim of the blue tail fly”

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

Jimmy, crack corn and I don’t care

My master’s gone away

Entomologically, the blue-tailed fly is a member of the genus Tabanus and is known in the vernacular as horseflies. They are quite large—about an inch long, and have razor-like mouthparts that they use to slash open the skin of their intended victim so that they can sop up a pool of blood that is created from the laceration. The bite of the fly is incredibly painful and horses will flee at the sound of their approach. So, the events described in the song are accurate. When the adult flies are out in force, it is wise to have some way of deterring the flies. Today, we use bug spray. But back in the 19th century, the task might have been assigned to a slave, whose job it was to make sure the master’s horse didn’t unseat him when the blue-tailed fly was out and about. As the song conveys, it was not a perfect system.

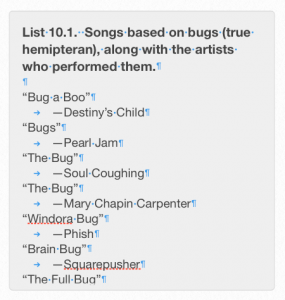

Although the Hemiptera don’t seem to fall as readily into the category as musical muse, you wouldn’t know that from the number of songs dedicated to the order. True bugs come up in song at least 10 times, with some artists offering multiple insect-based songs. Phish, for instance weighs in with “Windora Bug”, and Van Halen is back with “The Full Bug.” A more or less full accounting of bug-based popular music, along with the artist who performed them appears in List 10.1.

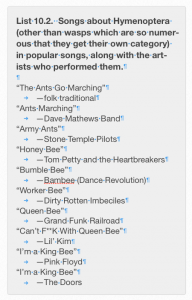

Just as with myth, religion, and classical music, the Hymenoptera are very well represented in popular music. The offerings vary from the fairly standard “Ants go Marching,” which is a folk traditional song, to “King Bee” by Pink Floyd and dozens of examples in between. Several different castes of bees have their own songs, e.g., “Queen Bee” by Grand Funk Railroad and “Worker Bee” by Dirty Rotten Imbecile, although it is clear that the insects are being used here as a metaphor (List 10.2).

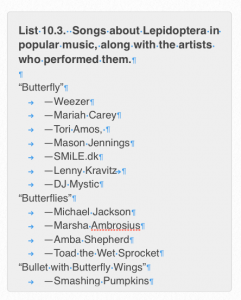

Despite the liberal use of insects in popular music, as with other forms of human expression, it is the Lepidoptera which bring down the house. There are so many examples that they can’t easily all be listed. Butterflies have been used as folk classics, in country western music, in acid rock, by sonorous crooners, and everything in between. List 10.3 lists a smattering of these musical offerings.

Although less visually stunning than the butterflies, moths also find their way into a variety of pop songs. Who could resist titles such as “Moth Eaten Deer Head,” recorded by the appropriately-named Locust?

As we leave the well represented orders of insects behind, it is appropriate to sign off with a tip of the hat to some which, although less sexy, also have made it into a song or two. Dragonflies have been written about by several bands and fleas have also made it into an occasional piece. Even some non-insect arthropods, especially spiders, have played the muse. From our childhood favorite “The Istsy Bitsy Spider” to “Spider in My Room” and “Boris the Spider” by the Doors, our evolutionary fear of spiders invades the nursery and the bar.

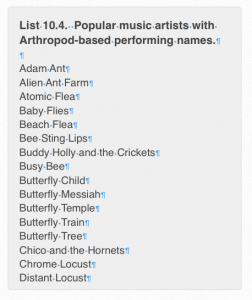

If insects make good musical themes, they also make excellent names for musical groups. There are literally dozens of musicians who have appropriated insect names for their musical groups. And more are being added all the time. List 10.4 gives a partial list of those artists who have adopted an arthropod identity as their artistic name.

Chapter Summary

As you have seen, insects have a niche in the creative part of our brain, which may defy reason, but which is unquestionably part of our culture. Insects appear regularly in musical compositions as a result of human fascination with the process of metamorphosis and other elements of the biology of insects that commend them for use in music. Even the use of an insect name in the title commands our attention and tells us that we’re about to hear something creepy or something elemental. Musicians are happy to use insects in music because they have the power to create soundscapes that of great meaning.

References

Chapter 10 Cover Photo:

Chrysalises: CC0 Public Domain, GLady. Accessed via pixabay.com

Music notes: CC0 Public Domain, GDJ. Accessed via pixabay.com

Video 10.1: Mikrokosmos No. 142 from Bela Bartok’s “Diary of a Fly”. Available on YouTube at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WNfrYRW-ZFM

Video 10.2: Flight of the Bumblebee” by Rimsky-Korsakov, performed by Katica Illenyi and the Gyor Philharmonic Orchestra. Available on YouTube at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vtAu7xkwNjQ&feature=youtu.be

Video 10.3: La Cucaracha (The Dancing Cockroach Video) by DARIA. Available on YouTube at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yfka9m6NhzE

List 10.1: Information compiled by S. W. Fisher and W. S. Klooster, from various sources

List 10.2: Information compiled by S. W. Fisher and W. S. Klooster, from various sources

List 10.3: Information compiled by S. W. Fisher and W. S. Klooster, from various sources

List 10.4: Information compiled by S. W. Fisher, from various sources

Additional Reading

Dethier, V. (1992). Crickets and Katydids, Concerts and Solos. Harvard University Press, Cambridge. 140 pages.