Chapter 11 – Fear of Insects

Fear of insects is both pervasive and understandable. In this chapter, we will try to understand its roots and how it can impact people—especially in severe cases. Finally, we will consider treatments for fear of insects and their effectiveness.

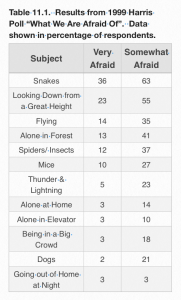

A Harris poll taken in 1999 reveals that people are afraid of lots of things (Table 11.1). Fear of snakes and heights rank highest on the list of scary things in this poll with almost everyone in the population being very afraid or somewhat afraid of both snakes and heights. Fear of insects falls in the middle of the list with 12% of respondents being very afraid of insects (and spiders) and an additional 37% indicating that they were somewhat or very afraid of bugs. So, all told, half of the people surveyed admitted to a significant fear of insects.

If we break the data down further, in this case by sex, we see that 19% of women responded that they are very afraid of insects, whereas only 4% of men admitted to that. So we learn that women are roughly five times more likely than men to be afraid of insects. Alternatively, it could be that women are more likely to admit their fear.

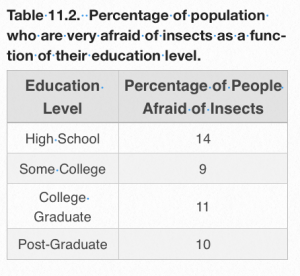

It is somewhat comforting that as educational levels increase, there is a slight decrease in fear of insects. People who had a high school education were the most fearful while respondents that attended college were slightly less fearful somewhat (Table 11.2). The levels of fear reported remained quite stable, not changing much among those that had graduated from college or received post-graduate education, suggesting that the benefit of education is realized quickly and doesn‘t change much with advanced education—unless perhaps one of your college residences was a basement that you shared with cockroaches and millipedes and silverfish. That could likely prolong your fear.

We might decide that fear of insects is just part of being human and that there’s no point in stressing out about it. However, a little thought reveals that fear of insects is a rich part of the human psyche that can be, on the one hand, protective and on the other, a significant pathology. To understand the nature of insect fear, we have to confront and define some key concepts. We will come to understand that fear of insects, as is the case for other common human fears, is rooted in our evolutionary past. Avoiding poisonous or disease-causing insects, for instance, would have had profound consequences for survival and, consequently, how many offspring we could leave. We will also see that treatment options are available but the effectiveness is frequently limited.

As previously noted, humans have cultivated a fear of insects as part of negotiating the challenges of our world. If we could learn to avoid harmful things, it could increase our capacity to survive and reproduce. Thus, being afraid of heights (read falling off a cliff) or snakes (you know, like vipers and adders) or wasps that leave painful stings and to which some people are very allergic increased the likelihood that our genes will make it into future generations. Unlike some fears, such as snakes, we are reminded of our proximity to insects on just about a daily basis. Ants invade our kitchens in search of food resources to share. Cockroaches scamper around human habitations with hygiene issues. Mosquitoes visit us nocturnally in most unwelcome ways and even in the dead of winter, we find insects when at long last, we take the time to clean the lamp shades. Yes, insects are a part of every day and every season. Even the intense urbanization of modern life does not eliminate our interactions with insects. And since we are evolutionarily designed to fear insects, it is not surprising, that sometimes the fear gets out of hand and becomes a genuinely debilitating pathology.

On the last point, we am joined by no less an authority than Professor Edward O. Wilson, an ant specialist from Harvard University. Although he has been an entomologist his entire life, he admits to what he terms a “slight” phobia of spiders. This is a curious matter. In addition to having studied and described at least 450 species of ants worldwide, Professor Wilson has come into contact with a fair number of spiders in his position of curator of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. Still, he says, he cannot bring himself to touch big hairy spiders.

His fear stems from an incident that took place when he was eight years old. He saw the huge web of an orb weaving spider and reached out to touch it. At just that time, the spider moved abruptly and, in Wilson’s recollection, in a way that frightened him greatly. Ever since that moment, he has had a fear of spiders.

While this sounds like a fairly ordinary and low level of arachnophobia, the insight that came from it is profound. Wilson believes that humans have a genetic underpinning that makes us afraid of things that can potentially hurt us. The trend has become exaggerated in humans to the extent that we have cultivated phobias about certain things like insects, snakes, and heights. These are all things that could have been lethal to us in our ancient life on the savannas of Africa. And, as a consequence, there was adaptive value in overextending a reasonable fear of things that could hurt is into a full blown phobia that would seem, at first blush, to be maladaptive. Wilson argues that during our hunter-gatherer years, the phobic fear of insects, snakes, and heights led to an abundance of caution on the part of our ancestors and that is how we became their descendants.

A final note of interest from Wilson is that phobias distinguish themselves by arising in the human mind after as few as one precipitating incident—as was the case for Wilson and his fear of spiders. In fact, humans are genetically programmed to have what appears to be an extreme reaction to a single stressor because, back in the days of the savannah, this was an adaptive trait. However, once instilled, phobias also have the characteristic of being difficult to expunge. Intensive therapy, reconditioning, and even drugs may make only marginal differences in our ability to tolerate the things about which we are phobic. In the modern world, that can cause a few problems.

In fact, our fears about insects are finely tuned enough that we can differentiate three distinct types of insect fear: 1) typical fear of insects or entomophobia; 2) delusionary parasitosis; and 3) illusionary parasitosis. Let’s begin with the regular fear of insects or entomophobia (which also includes arachnophobia and acarophobia). Entomophobia is defined as a persistent irrational fear of insects resulting in significant distress from the presence or thought of insects, and which is not due to any other mental condition.

Entomophobia

Entomophobia is distinct from the other conditions that involve fear of insects, i.e., delusionary parasitosis and illusionary parasitosis. These will be defined in a while. Entomophobia may accompany conditions like obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; think Sheldon from the Big Bang) but is not synonymous with it. Entomophobia is also not schizophrenia or other conditions found in the diagnostic manual of mental health.

As indicated previously, fear of insects at some level is actually healthy. We fear being stung by insects, for instance, and if you’re allergic to the venom, this fear can be life-saving. In modern society, we all know that some insects are capable of vectoring deadly diseases. So, limiting exposure to mosquitoes, ticks, or fleas is just common sense. In this case, increased understanding is both a blessing and a curse because it is not possible to avoid all interactions with insects, so there will always be some level of insect-induced stress. Even healthy people can experience indirect fear of insects such as hearing about the plague in the middle ages and realizing that both the plague bacterium and the vector, the rat flea, are both present in modern times, and there are occasionally outbreaks in the southwestern US.

Delusionary Parasitosis

Delusionary parasitosis (DP) is related to but much more extreme than entomophobia. Clinically speaking, DP is the firm and unshakable belief that live insects (well, usually insects, but sometimes worms or bacteria) are present in your skin. While it is tempting to think of DP as a single condition with a single source, it is often part of a suite of symptoms that makes it much more difficult to diagnose and treat. However, the delusions about insects may be the easiest to identify and, thus, become the focus for treatment. Understanding the source or the precipitating incident, e.g., drug-induced brain damage, a bad case of dermatitis, or various kinds of psychosis may be important to effective treatment.

Unfortunately DP clients or patients often darken the doorway of entomologists, whose first reaction is usually “Oh no, another one.” When they find you, you know that they already have been many other places and have found the response unsatisfactory. Typically, they will shop around until they find a willing ear. They will regale you with their entire life history from embryo-hood onward. In many cases, they are not particularly interested in getting better and will rebuff any suggestions that don’t fit their pre-determined paradigm. They will take immense amounts of time and will probably not be helped in the end.

At the first encounter (and there will be many if you permit it), DP patients will report a variety of problems, e.g., biting and burning sensations on multiple body parts; crawling sensations under the skin, often with intense itching. Often, the client will pull back his or her hair to reveal black specks which are only visible to them. Some are convinced that bugs can eat through shoes and invade the body through the feet. They will point to scabs which they are sure are bugs when, in fact, they are merely scabs and probably produced by their own scratching activity. Many are convinced that bugs are hiding all over the house and are capable of jumping on them. Life for these people is an ongoing nightmare of insect assaults on their body which causes grief, fear and misunderstanding.

DP patients and clients also are prone to re-writing entomology texts. They are convinced that new and unreported life cycles and habits are in play and are searching for a competent entomologist or physician who understands this. Actually, anyone who agrees with the patient’s diagnosis will find favor. Those who question the self-diagnosis will be found wanting, regardless of their professional credentials. Among common complaints, DP patients often say they are infested by bugs that begin as black flecks in the environment but change to white globs once they invade the skin. Many are convinced that eggs deposited under the skin hatch and larvae then crawl around in the body. Lint balls in the house are viewed as breeding grounds for invading bugs and some even believe that insects are capable of living in the human stomach (with a pH of 2.0), can migrate around the body, and will eventually emerge through the anus (like pinworms) before re-infesting the body through the skin.

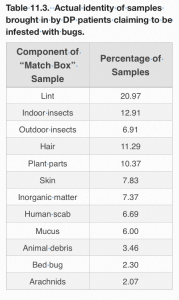

Ms. Barb Bloetscher, State Entomologist and State Apiarist for the State of Ohio was the diagnostician at The Ohio State University Plant and Pest Diagnostic Clinic for many years. As a result, she has dealt with dozens of people with DP, many of whom found her after years of unsuccessful interaction with the medical community. She has collected data that help to define the scope of the problem. When clients call complaining of having been infested by insects, they are encouraged to bring a sample of their “bug” to the clinic. Thus, ensues the “matchbox” presentation in which a client will bring a matchbox or similar type of container in which she (or he) claims the offending bug is located. Table 11.3 shows the identity of the “bug” in matchbox samples brought to the clinic over a three year period. The majority of the samples (21%) contained only lint. Another 20% consisted of actual insects collected either from inside or outside the house. In no case were these insects capable of invading and living in a human being. After that, the list gets quite variable with a lot of human hair, scabs, mucus (yuck!), and miscellaneous debris.

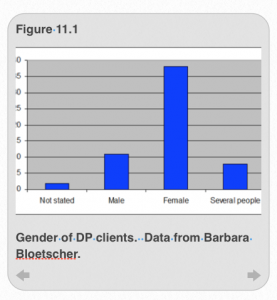

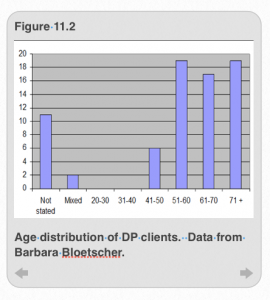

Ms. Bloetscher reports a demographic bias in the samples with women being three times as likely to complain about being infested by insects (Figure 11.1), consistent with the polling data discussed earlier. In addition, people older than 50 tended to be predominate among those presenting samples for analysis (Figure 11.2).

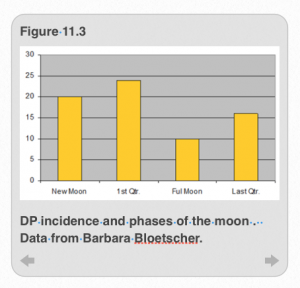

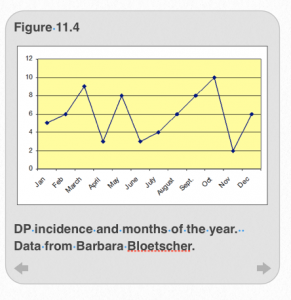

There is even a strange correlation with people reporting infestation by insects and phases of the moon (Figure 11.3) and seasons of the year (Figure 11.4). Curiously, a greater number of samples came in during a new or first quarter moon and the data also show a distinct bias towards being more numerous during the months of March, May, and October. These findings are, no doubt, matters of coincidence rather than cause and effect.

Other scientific studies have found that people generally start suffering from DP after undergoing a traumatic life event, like loosing a job or loved one, or having a medical condition that keeps them home and bedridden. The typical DP patient is a woman over 60. Most often, she will be the only person in the house affected (which is a signal that DP may be the problem) and the person is often homebound, ill from some organic disease, recently had surgery, or is recovering from some sort of accident. These folks have a lot of time alone to think about themselves and to do research on the internet. While the latter can be a valuable source of information, it can also confirm completely unscientific and unfounded opinions, thus causing a person suffering from DP to believe that she has evidence of a problem that does not actually exist.

Despite the fact that DP is a state that isn’t real, it is very important to realize and understand that the client truly and genuinely believes that she is infested with insects. That is the reality that she experiences. This is one of the key reasons that DP is different from entomophobia, where there is simply a profound and abiding fear of insects. Because both the prognosis and treatment of the two conditions are different, it is critical to have an accurate diagnosis.

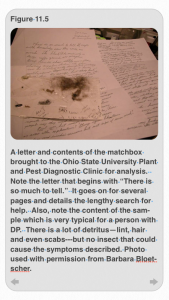

With this as background, you’re ready to meet actual people suffering from DP. At the first encounter, you’re likely to be given an extensive, usually handwritten chronicle of the infestation (Figure 11.5). As you can see, the first letter begins with the sentence: “There is so much to tell.” This is classic. The DP client’s life has become consumed by DP. She is invested in its truth. There is nothing more important than discussing this issue. You will also be given a baggie or a matchbox with “the evidence.” As previously noted, most often it will contain lint or normal household insects that are not a threat.

If you meet a person with DP, very often you will be presented with a bunch of sticky notes with symptoms or a chronology on them (Figure 11.6). These can be quite extensive and, for the most part, completely irrelevant.

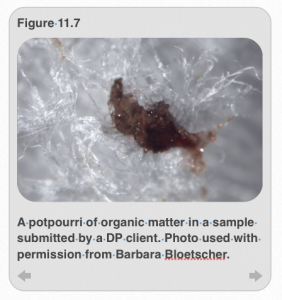

And if you permit it, DP clients may present a smorgasbord of “insect samples” that include those nasty lint balls with some scabs, blood, bone fragments, and mucus thrown in for good measure (Figure 11.7). They almost certainly will not contain any insects that can cause the harm that the DP client reports.

Some DP clients have really gone around the bend. Here’s an example of a person with extreme DP. She used to be a homeopathic licensed practical nurse (LPN) but was then stricken with the idea that she had intestinal worms that somehow morphed into globs in her body. She described scratching an egg mass (not clear where it came from) that precipitated a “grand hatch” in her body. The client was convinced that the worms would find their way into her stomach. Because she couldn’t get anyone in the medical community to believe her, she began to self-medicate by ingesting 9 mg of ivermectin every day for four days followed by seven days off. Ivermectin is a pesticide that is used to treat fleas in dogs, and intestinal worms in horses. However, it is a strong neurotoxin and has to be used with a great deal of care. Nonetheless, the DP client used this treatment for five years!! This is extremely dangerous and very illegal. Nonetheless, she went so far as to recommend the treatment to others with the affliction.

In another very sad extreme case of DP, a man named Steve presented to the clinic. He reported having egg masses under his skin. He was convinced that they had hatched and spread throughout his body. As a consequence, he felt compelled to dig the worms out with a knife. When he came to the clinic, Steve was covered in scars and fresh wounds, many of which were infected. The clinician referred Steve to the Ohio Department of Health which sent him to the hospital. The bugs that were after Steve were never found.

Far from being unusual, folks with DP often feel the need to resolve their problem by digging the bug out with a knife. Telltale scars of gouging the skin with a knife are a common finding with DP, and are generally more common among men (Figure 11.8).

A third case illustrates the devastation that DP can bring. This client, named Mike, described how “bugs” were hiding in the walls, furniture and wooden kitchen tools in his home. These bugs were strong and could eat through wood, steel, and plaster. Steve thought they could even enter the house through the roof. Once inside, they took up residence in Mike, penetrating through his skin and invading his stomach. As reported by others, the parasites underwent “hatchings.” The hatched worms or larvae then traveled various places inside his body before moving outside of his body, following which, they reinvaded his skin. As a result of this obsession which couldn’t be successfully treated, Mike lost his family, his house, and a great deal of money.

In coming to grips with DP, it is extremely important to understand the client’s perspective—not that you have to agree with it but you do need to empathize with them. If you suggest that a DP client might have mental health issues, they will immediately retort that they are not crazy. They will insist that the biting and infestation are completely real but that no one believes them. They truly believe that doctors are not well trained and, therefore, can’t see what is obvious to them. Buttressed by lots and lots of (frequently) erroneous material on the internet, their belief deepens. They also believe that the bugs are capable of jumping off, burrowing, or generally hiding, and that is why they cannot be found by physicians or by entomologists. They will also suggest that the bugs are new to the U.S. and that’s why they can’t be identified. The main point is that DP clients absolutely believe that they are infested. The bugs are real to them. The fact that no one else can see or perceive them is just further proof that they alone have the truth.

Entomologists have a slightly different perspective about DP. They are likely to say to DP clients that no known arthropod fits the description of the bug with which they’re infested. Naïve entomologists will tell them that they need “counseling” by which they mean psychiatric help. This suggestion will be scoffed at or met with outright hostility. The entomologist will explain that there is no such bug as the one the client is describing but this will not deter the client from insisting on his mystery bug. In the end, the interaction may be limited by the fact that it takes a great deal of time to process the samples brought by the client and they are almost never interested in paying for the service. The entomologist will probably be driven to cut off the interaction after one or two visits.

If the client can be persuaded to report to a public health clinic, the clinician may suggest other conditions that might account for the symptoms, e.g., allergies, contaminants, reactions to drugs, or problems with ventilation. They may make recommendations such as stopping all self-medications or pesticide treatments. However, one of the most important things they can do is to listen for evidence of some sort of trauma—something that could have precipitated the DP. If they can do that, it may help the client to understand the source of the problem.

Unfortunately, the reality is that the kind of help that an entomologist or clinician can provide to a person suffering from DP is limited. However, there are some small things that can have a big impact. Both should listen carefully, take notes, and be respectful. A sympathetic tone is good although it is important not to endorse mistaken ideas. If the family of the DP client is willing participate in the discussion, this can be helpful both in dispelling erroneous information and encouraging a more reality-based understanding of the problem. This can be substantiated by providing fact sheets or other authoritative materials about insects and their lifecycles, the goal of which is to countermand the fanciful notions the client may have developed about insects. The discussion will be most helpful if one can slowly build a sense of control in the client which is based in fact. Additionally, it is wonderful if the client can be persuaded to seek mental health treatment but that will probably be a long-term rather than short-term goal.

If the client is lucky enough to find help in the medical community, the interaction tends not to last very long. Although DP is more common than most medical doctors are likely to acknowledge, there is little in the way of standard protocols for dealing with it. Often, dermatologists are the first line of defense who, after unsuccessful treatment, will refer the patient either to an entomologist or pest control operator or psychiatrist. Another approach is to offer a placebo in hopes that it will provide some psychological relief and get the recalcitrant patient out of his office.

If the client does visit a psychiatrist, a range of treatments can been tried. The range extends from drugs to control symptoms, to talk therapy to address repressed conflicts over things that have nothing to do with insects, to even more aggressive therapies such as ECT (electroconvulsive therapy), although this has fallen out of favor.

Perhaps the biggest advance in treatment could be achieved by better communication and more sophisticated treatment protocols on the medical side of things. Dermatologists correctly say that they can’t treat delusions but the typical client will not receive a suggestion that he see a psychiatrist with enthusiasm. It is probably better for the patient to at least receive palliative drugs like pimozide to relieve the itching than to receive no treatment at all. Still, if no one is addressing the underlying causes, it is unlikely that DP will go away on its own.

A proposed triage system has been developed to deal with DP patients in the medical community. If depression or psychosis is evident in a DP patient, he should be referred to a psychiatrist. He or she needs medication and the psychiatrist is the only one on the call list who can do it. If, however, the patient is aware of his own emotional involvement in his condition, he might be treated by a psychotherapist who will use talk therapy and behavior modification to treat the client. If the patient cannot admit to his investment in his condition and will not hear of a psychiatrist, the best course of action may be a referral to a dermatologist to treat the symptoms. In all cases, progress may be minimal until the patient loses enough—his job, his family etc.—that he is willing to entertain that which was previously unthinkable: his condition is not real or, more specifically, it is real to him but to no one else. For all of these reasons, the medical community does not like treating DP patients, making it even more likely that a DP client will eventually call a very unprepared entomologist.

The prognosis for folks with DP is variable and depends on which other complicating conditions, which may or may not have been diagnosed, are present. DP is usually a combination of problems of which the insect-related ones are easiest to see and understand. In extreme cases, DP may be part of a schizophrenic or other pathology. In those cases, the prognosis is much less favorable.

Of course, one absolutely critical element of treatment is to specifically rule out an insect infestation. Unfortunately, some people actually do have insect problems and it is sometimes simply hard to find the offending creature—especially if a trained entomologist is not called. There is a specific case in the literature in which a woman complained for seven years that she was infested with bugs under her skin. However, the skin lesions with which she presented were considered proof—not of an insect problem, but of an underlying psychosis. She was, thus, referred to a psychiatrist. In the end, it turned out that she had been infested by a mite, Dermatophagoides shermetewskyi, which, unlike the scabies mite, doesn’t leave telltale epidermal burrows. For this reason, it is always a good idea to have an entomologist investigate a putative case of DP before concluding that it is all in the client’s head.

Illusionary Parasitosis

The final entomological condition worthy of attention is another insect-related pathology called illusionary parasitosis (IP) which is quite distinct from its cousin, DP. Rather than affecting a single individual, IP is a group phenomenon, and results from stimuli in the environment. The stimuli are real but are incorrectly interpreted as something involving insects. Because IP typically involves a group reaction, it is sometimes referred to as mass entomophobia but it is distinct both from entomophobia and DP.

The symptoms of IP include itching, dermatitis, and bites. Once detected by one or a small number of people, the symptoms can spread rapidly among a group as large as 100-150. People who are unaffected may report sympathetic symptoms. As with the other insect-based pathologies, women are more likely to be affected than men. Often, there are elements in the environment that make it more likely that IP will break out. These things include poor sanitation, an unfriendly work environment, dull work routine, or too much time on one’s hands. Group symptoms may follow an actual outbreak of insects that is subsequently resolved. Usually the problem that gets fixed is completely unrelated to insects. For instance, cable mites or paper lice, neither of which are real, might be adduced to explain itching among co-workers when the actual problem is a build up of static electricity or irritating microfibers coming through a ventilation system.

As with DP, the first task is to rule out an actual entomological cause. This can be a forensic process in which ostensible causes such as insects are progressively ruled out. If, in the process, the actual source of the irritation can be detected and removed, the IP symptoms should resolve quickly. Additionally, changes in the work environment to relieve stress and poor hygiene can be fruitful. Of the three types of conditions that stem from fear of insects, this is probably the one that is most amenable to treatment and a reasonably quick solution.

Chapter Summary

The take-home message from this chapter is the following: fear of insects is real and has identifiable roots in our evolution. Sixty thousand years ago, fearing insects was an adaptive feature of our psychology that likely increased the ability of our ancestors to survive in a world fraught with danger—some of it coming from insects and other arthropods. In modern times the danger coming from insects is, for the most part, gone but nonetheless, the fear persists and, in some people, takes on much more debilitating aspects than simple fear of insects. Careful diagnosis from a competent entomologist is absolutely required any time a client or patient reports conditions such as DP or IP. Entomophobia can usually be managed by avoiding contact with insects (or arthropods) that are feared, and, in extreme cases, seeking desensitization therapy to lessen the fear.

References

Chapter 11 Cover Photo:

Fear emoticon clipart. Free clipart from clipartfest.com

Table 11.1: Information from 1999 Harris Poll: “What We Are Afraid Of”

Table 11.2: Information from 1999 Harris Poll: “What We Are Afraid Of”

Table 11.3: Data from Ms. Barbara Bloetscher. Used with permission.

Figure 11.1: Data and figure from Ms. Barbara Bloetscher, own work. Used with permission.

Figure 11.2: Data and figure from Ms. Barbara Bloetscher, own work. Used with permission.

Figure 11.3: Data and figure from Ms. Barbara Bloetscher, own work. Used with permission.

Figure 11.4: Data and figure from Ms. Barbara Bloetscher, own work. Used with permission.

Figure 11.5: Photo credit: Ms. Barbara Bloetscher, own work. Used with permission.

Figure 11.6: Photo credit: Ms. Barbara Bloetscher, own work. Used with permission.

Figure 11.7: Photo credit: Ms. Barbara Bloetscher, own work. Used with permission.

Figure 11.8: Photo credit: Ms. Barbara Bloetscher, own work. Used with permission.

Additional Readings

Cloyd, R. A. (2013). Secrets of the “Big Bugs.” Special Effects in 1950s Science Fiction Movies. American Entomologist 59: 203-207.

Lockwood, J. A. (2013). “The Infested Mind: Why Humans Fear, Loathe and Love Insects.” Cambridge University Press, New York, 230 pages.

Wilson, E.O. (2014). “The Meaning of Human Existence.” Liveright Publishing Corporation, New York., 207 pp.