Chapter 16 – Effects of Plague on Art and Literature

The arrival of the Black Death in 14th century Europe left no one untouched. Attempts to understand the devastation that played out on a daily basis were overshadowed by the reality that frightened people put their own preservation first and, in many cases, abandoned the responsibilities that their positions required in order for society to function. Ripple upon ripple of despair bludgeoned the spirit. Omnipresent death, memorialized in the phrase memento mori (memory of death), replaced previously normal modes of thought. A pervasive notion that all was lost became firmly rooted in the medieval mind. Such a mindset would, of course, have catastrophic effects on the way the survivors understood the world and upon the society of which they were a part.

Impact of Plague on Visual Art

The Black Death was captured vividly in the visual arts—both from the time of the plague and in more contemporary works. In many cases, the bewilderment and resignation of the inhabitants were poignantly captured by the artists. Medieval art is described as darker in style than that which came before or after it, for understandable reasons. To make sense of the darkness, painters were particularly prolific in expressing the pain and devastation in a visual form.

The interesting aspect of this painting from Florence, Italy (Figure 16.1) is that it is an attempt to capture daily life during the time of the plague. Ostensibly a street scene in a European city, it is not a pleasant time. In the background, a man guides a woman away from the carnage in the street. A man in the foreground holds his garment over his face to deaden the smell of death that pervades the air. Sick people line the doorways of houses or the sides of buildings waiting to die. In the foreground, an entire family, man, woman and child, lie dead. A few workers try to remove the dead from the street, but their task is never-ending. By the time they take care of the first body, more will have died. There will be no end to the bodies. And, this, of course, meant that the habits we have cultivated as a society to deal with death will fall by the wayside, increasing the devastation further.

In medieval Europe, it was unthinkable that one would die without first having a priest present to give last rites. As the plague wore on, many priests died from the plague. The ones who remained were too few to attend the dying or they may have actively refused, realizing that the dead might very well infect the priest. Even those who were lucky enough to have a priest at their death bed might still experience great ignominy once they drew their final breath. It would have been usual at the time for people of wealth to be buried in subterranean catacombs outside of the city to keep hygiene at as high a level as possible. The wealthy would be buried in clothes and with objects that reflected their exalted status. Their graves might be marked with a golden placard. Those who had some money but were not rich might have been buried in a church—as close to the altar as possible to increase their chances of salvation. But, as this painting shows, the system broke down. The dead were not attended and, as time went on, were left to die and, after death, to accumulate in the streets.

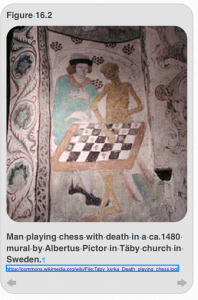

Does death have a sense of humor? Does humor normalize society when it is buffeted by forces that cannot be controlled or adequately understood? In the mural by Albertus Pictor (Figure 16.2), we see a nobleman playing chess with death. If he wins, does he get to live? Even the smallest feeling that one can do something to control the outcome might have meant the difference between survival and lethal despair. This theme was later recycled in Ingmar Berman’s “Seventh Seal.”

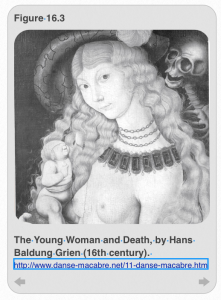

A European zest for life was replaced, after the introduction of the plague, with a belief that their future was only death. The painting in Figure 16.3 (The Young Woman and Death) shows death in the form of a skeleton peering over the shoulder of a vane young woman who would ordinarily be thinking about more congenial things. But, in the time of the plague, everything was death.

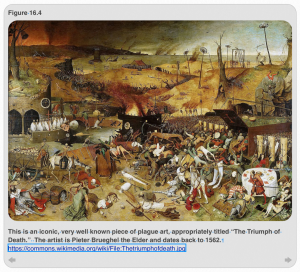

The next image (Figure 16.4) is an iconic, very well-known piece of plague art, appropriately titled “The Triumph of Death.” The artist is Pieter Brueghel the Elder and dates back to 1562. Is this a depiction of the end of the world? The sky in the background is black—perhaps with smoke due to burning bodies? Upon the waters, we see ships that are wrecked. Could they have run aground because their inhabitants died at the oars of plague? Skeletons are everywhere among the living. Skeletons even attack those that yet alive. A boat full of skeleta floats by while a few of the living are either trying to tend the dead or, perhaps, loot them of valuables. A skeleton even appears on horseback with a scythe to dispatch a few more souls to the great beyond. Is it a skeletal horseman of the apocalypse? Even the horse cannot muster much in the way of flesh. A dog eats the flesh of a child while those few who are still ambulatory try to escape through a tunnel lined with crosses. The message is pretty clearly that it will do them no good. Is this what the end of the world looks like?

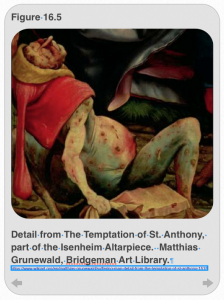

And finally, Figure 16.5 shows another very well known piece of plague art (Detail from Isenheim Altarpiece, by Matthias Grunewald ca. 1510-1515). The body of the man pictured is riddled with buboes. This, of course, is bad enough but the posture of the man conveys the agony that they cause. His head is tilted back, possibly a response to buboes in the cervical or neck region which are very painful. The lurching of the head is an attempt to find a position that lessens the pain. Or this could be neurological effect of plague that causes the victim to gesticulate in bizarre and uncontrolled ways. Unfortunately, the pain cannot be escaped—either in a physical sense and a spiritual one. The hand of the victim clutches desperately at a piece of cloth in the foreground trying to escape the pain. But this is only increased by the realization that he will most certainly die and will do so without assistance either medical or spiritual.

Plague and the Performing Arts

Danse Macabre

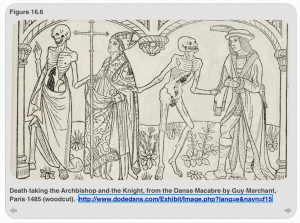

Even in times of great emotional travail, people gravitate to music and dance as a form of expression. The Danse Macabre is one of the lasting contributions of the Black Death to the arts. Scholars suggest that the Danse Macabre was probably first performed as a dance, then rendered into poetic form and, finally, became the subject of visual arts in a variety of paintings and woodcuts. One such image, by Guy Marchant in 1485, is featured here (Figure 16.6). he essence of the art form, whatever its representation, is to show living humans dancing with skeletons. The message could not be more clear: you may dance with the living today, but your future is with the skeletons. Memento mori writ large. The feeling of despair in the paintings was augmented by having the dancing skeleta often appear in grotesque, misshapen forms. And just to leaven the impact a little, often noblemen as well as peasants would appear as dancers. Death, at least, can be said to have a sense of poetic justice. Nonetheless, the impact of being danced off to hell, no matter how well dressed one is in life, could not help but be horrifying. To increase the horror, the skeleta were sometimes represented as pulling on or tugging at the living to advance their progression towards damnation.

Plague in Song and Music

We like to capture all human emotions in music. Even in the absence of words to convey meaning, music has the mysterious power to bypass the parts of our brain that require cognition and go straight to the emotional centers. As a result, every mood can be captured in music and we have every reason to suspect that emotions that were running at a fevered pitch during the time of the Black Death would have been rendered into music.

This assertion is not hypothetical but has been the source of scholarly study in modern times. Dr. Christopher Macklin, Professor of Musicology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, for instance, has explicitly studied the relationship between the scourge of The Black Death and music. Among his findings, Macklin suggests that it is highly likely that the piece of music entitled O Sancte Sebastiane by Guillame Dufay was very important to medieval people who were suffering through the plague. The Saint Sebastian of the song is believed to have helped defend Rome when an earlier epidemic of Plague spread through in 680. In fact, Saint Sebastian achieved sainthood because he survived multiple arrow wounds; arrows were often depicted as the symbol of the plague.

Macklin also explored the ways in which music helps to conceptualize lethal illness such as the plague and AIDS. In addition, because the performance of music is an ephemeral expression of art, particularly before the advent of the means to record performances, Macklin makes the case that the emotional force of The Black Death in music can be gleaned by the study of a 15th century piece, Stella Celi Extirpavit. The plague was still cycling through Europe during the 15th century so its impact would not be mysterious during this later time. Thus, the Stella Celi Extirpavit (lyrics following) would likely have sprung from the same mindset that existed during the time of The Black Death. Boccaccio argued in The Decameron that one function of music during the time of The Black Death was to divert sufferers from the misery that surrounded them. In fact, each of the 10 characters that appeared in The Decameron had written for them a verse that they were to sing. Similarly, King Henry VIII, himself, went into isolation at Windsor Castle to avoid the plague, allowing only a handful of people whom he felt he could not live without to remain with him: three courtiers, his physician, and an Italian organ virtuoso. What is isolation without music, after all?

The lyrics of Stella Celi Extirpavit make very explicit the fear and dread of those who endured the Black Death:

Star of Heaven

Star of Heaven

who nourished the Lord

and rooted up the plague of death

which our first parents planted;

may that star now deign

to hold in check the constellations

whose strife grants the people

the ulcers of a terrible death.

O glorious star of the sea,

save us from the plague.

Hear us: for your Son

who honors you denies you nothing.

Jesus, save us, for whom

the Virgin Mother prays to you.

The poem has been used in various ways over the centuries. One of these uses was to set it to music and use it as a hymn. The words make its purpose clear: it is an incantation to God to stem the misery of the plague which is specifically referenced as the source of that suffering. Note also the identification of the “ulcers of death,” an allusion to buboes. This piece very nicely encapsulates the medieval preoccupation with salvation and ways in which they would have appealed to God for relief from the devastation of the plague.

“A Sickly Season” is another poem that found musical form that was created to give expression to the misery and fear produced by the Black Death:

“A sickly season,” the merchant said,

The town I left was filled with dead,

And everywhere these queer red flies

Crawled upon the corpses’ eyes,

Eating them away.

“Fair make you sick,: the merchant said,

“They crawled upon the wine and bread.

Pale priests with oil and books,

Bulging eyes and crazy looks,

Dropping like the flies.”

“I had to laugh,” the merchant said,

“The doctors purged, and dosed and bled;

And proved through solemn disputation

The cause lay in some constellation.

Then they began to die.”

“First they sneezed,” the merchant said,

“And then they turned the brightest red,

Begged for water, then fell back.

With bulging eyes and face turned black,

They waited for the flies.”

“I came away,” the merchant said,

“You can’t do business with the dead.

So I’ve come here to ply my trade.

You’ll find this to be a fine brocade.”

And then he sneezed.

Among the points made so sharply by this piece is the inability of religion to deliver parishioners from the plague. Likewise, physicians, busy ascribing the cause of the plague to the stars, were themselves succumbing to the disease. But, then, even the merchant who sings the song is also stricken and will likely join those he derided in the grave. Death was an equal opportunity avenger. Who wouldn’t be in mortal fear all of the time when the inevitability of experiencing a horrible death seemed all but certain?

Finally, children may also have been dragged into daily recognition of the plague, although the attributions that suggest that this particular song was written during the time of The Black Death are not true. However, the lyrics may, in fact, be a tribute to the plague. The nursery rhyme in question is:

Ring around the Rosie.

Pocket full of posie.

Ashes, ashes

We all fall down.

Here, the ring in question could be a reference to a dance, perhaps the Dance Macabre, which takes place in a circle. Another suggestion is that it refers to a circular arrangement of buboes on the human body. The posie alluded to in the second line is ostensibly plant material that was thought to ward off the plague. Ashes, ashes is allegedly the sound people make when they sneeze, potentially spreading the bloody sputum that perpetuates the pneumonic form of the disease. Finally, falling down takes place when one expires from the plague. Again, this rhyme was not written until the 19th century, as far as we can tell, so it is not something that children stricken with The Black Death would have sung or used it to ward off getting sick. But, it may have been used for these purposes by children in later centuries when the plague was still active in Europe. Today, it is simply an innocuous rhyme that we learn in childhood.

Plague and Literature

The most famous piece of fiction to be penned during the time of The Black Death was The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio written during the years 1350–1351. The book is an allegory that, among other things, documents the nature of life in the 14th century. Structurally, the book consists of a series of novellas that chronicle the escape of 10 young people (7 women and 3 men) who are attempting to flee the plague in Florence by retreating to a villa in the countryside. While there, they tell each other stories every night to pass the time. Each person tells one story each night and over a period of 2 weeks at the villa, 100 stories are collected to frame the narrative. The stories deal with love, tricks people play on one another, virtue, the power of human will and the immorality and greed of the clergy. A theme running through The Decameron is that of Lady Luck and the idea that one’s fortunes can rise or fall precipitously as the Wheel of Fortune turns. Another element in the book is that Boccaccio uses allegory to tie specific themes in Christianity to events that occur in the book. No friend of the church, Boccaccio’s purpose is not to educate the reader but to satirize the church. As would be understandable, the occurrence of the plague and the inability of the clergy to stop it, as well as a rising contempt for the excesses of the church, made the clergy an irresistible target.

Also writing during the time of The Black Death was Geoffrey Chaucer. Born in London in the early 1340s, he was a young child during The Black Death and only lived until 1400. During his short life, however, he became a very influential poet whose work continues to be widely read today. Certainly, one of the most read works by Chaucer is The Canterbury Tales, a series of 24 stories that comprises roughly 17,000 lines. The two main characters were the Pardoner who expiated sin through the selling of indulgences and the Summoner who rounded up and brought people to account for sins. Both men were deeply corrupt having liberally committed the very sins for which they were holding others to account. Death is a pervasive theme in The Canterbury Tales as is the notion that we atone for sin through death. The plague appears in different places in The Canterbury Tales as the agent of death, notably in the General Prologue and in the Pardoner’s Tale. As in The Decameron, plague is mixed with an omnipresent fear of death and the extortion of that fear by unscrupulous people, many of them members of the clergy, to achieve their desired ends.

Chapter Summary

It is, perhaps, a comfort to learn that even in times of great devastation, the creative muse continues to sing. In the time of The Black Death, the voice of the muse was one element of humanity that could be relied upon. Neither medicine nor God was sufficient to curb the plague. But the human spirit continued to live in the art and literature that was created during this period and the capacity for creativity even under the direst circumstances should give us hope for the future.

References

Chapter 16 Cover Photo: The Black Death in Europe. Author Unknown. Accessed via https://www.scoopwhoop.com/insane-cures-to-everyday-problems/#.jjr4hwndy

Figure 16.1: The Black Death in Florence, Italy in 1348. Reportedly by “Marcello”. Accessed via https://fathertheo.wordpress.com/2013/05/06/boccaccio-the-black-death-comes-to-florence/

Figure 16.2: Man playing chess with death. Mural by Albertus Pictor in Täby church in Sweden. Photograph of mural, CC-BY 2.5: Håkan Svensson (Xauxa). Accessed via https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taby_kyrka_Death_playing_chess.jpg

Figure 16.3: The Young Woman and Death, by Hans Baldung Grien (16th century). Accessed via http://www.danse-macabre.net/11-danse-macabre.htm

Figure 16.4: The Triumph of Death.” by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, 1562. Image CC0 Public Domain: Museo del Prado. Accessed via https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thetriumphofdeath.jpg

Figure 16.5: Detail from Isenheim Altarpiece, by Matthias Grunewald ca. 1510-1515. CC0 Public Domain. Accessed via https://www.wikiart.org/en/matthias-grunewald/suffering-man-detail-from-the-temptation-of-st-anthony-1515

Figure 16.6: Danse Macabre. By Guy Marchant, 1485. Accessed via http://www.dodedans.com/Exhibit/Image.php?lang=e&navn=f15

Additional Readings

Ariàs, Phillippe. The Hour of Our Death. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981.Beidler, P.G. (1982). The Plague and Chaucer’s Pardoner. The Chaucer Review 16: 257-269.

Binion, R. 2004. Europe’s culture of death. Journal of Psychohistory 31:395-412.

Binski, Paul. Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1996.

Cohen, J. 1982. Death and the Danse Macabre. History Today.

Judith M. Bennett and C. Warren Hollister (2006). Medieval Europe: A Short History. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 372. ISBN 0-07-295515-5. OCLC 56615921

Macklin, C. (2010). Plague, Performance, and the Elusive History of the Stella Celi Extirpavit. Early Music History doi:10.1017/S0261127910000057.

Norman, D, (ed) Siena, Florence and Padua: Art, Society and Religion 1280-1400, Vol 1, Yale University Press 1995, at 19.