Chapter 17 – Effects of Plague on Medieval Society

In the middle ages, time moved slowly. With the coming of the Black Death, however, change took place on an accelerated scale. Depending on whose numbers are correct, somewhere between a quarter and half the population of Europe disappeared in a three-year period. Imagine the consequences if such a thing were to happen today. The wheels that grind to make life possible, the institutions and people who run them would be very hard pressed to keep things going. And, during the Black Death, when the ability to communicate was considerably lower than it is today and the ability to assess and understand the causes of the pageant of death that was playing out before medieval eyes was likewise impoverished. As a result, it is simply unfathomable how people dealt with the devastation. It does, however, teach much about human psychology and the human spirit. Our task in this chapter is to examine three societal institutions: medicine, religion, and government to see how they reacted to the plague; how helpful those institutions were during the time of the plague; what factors limited their effectiveness; and how all of this affected people’s understanding of and response to the plague.

Physicians and the Black Death

It is difficult and certainly uncharitable to deride medieval physicians for their inability to enact effective responses to the bubonic plague during the 14th century. They were products of their time. Their understanding of the cause of disease was lodged in a different millennium. Their ability to stem the spread of plague was severely limited by that understanding and the fact that the conditions that prevailed in medieval habitations exacerbated the spread of the plague. Nonetheless, it is instructive to examine the factors that were in play in medieval medicine that impacted the spread of the disease.

No one, most particularly physicians, understood what caused the plague. The Germ Theory of Disease was still centuries away (see Chapter 24). There was no understanding that the invisible agents that we call germs or pathogens could be passed not only from person to person, but from rats and fleas to people and, in some cases, through the air. As a result, there would be no attempt to control rats or fleas, thus assuring that all of the elements of plague transmission would be unfettered in their ability to transmit plague. This, of course, was exacerbated by the reality that in medieval times, disposal of bodies was a fairly crude undertaking (pun intended). There was understanding that it was unhygienic to have dead bodies lying around.

As previously discussed, burial of the dead was the usual practice. But handling of the dead bodies was crude as was the interaction of caretakers with the sick and dying. Washing one’s hands had not yet become an accepted practice following the treatment of sick patients. Indeed, physicians themselves were fairly efficient in spreading disease between patients because they did not wash their hands as a matter of course. Particularly in the case of someone who was sick with pneumonic plague, there would have been little protection of caretakers from the bloody sputum, which can infect without fleas (refer back to Chapter 15, Table 15.1). Finally, medieval houses and cities would have been littered with debris that supported the breeding of fleas and rats, increasing the likelihood that the biological players in plague transmission would have all been present. As time went on and more people died, the ability to carry out hygienic disposal of bodies, keep the streets clean and exercise caution in the care of the sick would all diminish and, with it, the spread of the plague would increase.

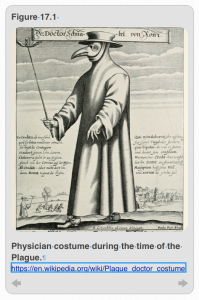

Medieval physicians did get one thing right when judged by modern standards and that was to develop a protective suit to be donned when attending plague patients (Figure 17.1). The complete costume made the physician look more like a crazed bird than a helpful friend. But the head mask did, perhaps have some function in retarding the spread of the disease from a sick patient to the doctor. The mask featured a filter in the part of the mask that looks like a beak, and was typically filled with dried herbs, flowers, spices, etc. to help keep out the “wykkid heires” (or as we would read them, “wicked airs”). In addition, the mask was outfitted with goggles that covered the physician’s eyes and were thought to protect the physician from the “haze,” which was probably a reference to the miasma they believed caused the plague.

This is not to say that those in the medical profession did not try to be helpful in this crisis. They published a series of tractates to be disseminated to the public offering helpful (for the time) suggestions. These included such ideas as admonishing medieval people to “flee wikkyd heires” (flee wicked airs), an idea firmly rooted in the miasmatic theory of plague transmission, but likely spread the plague to new areas and communities. Also, people were advised to keep a good humor, embrace cheerfulness, and spend one’s leisure time (presumably when not burying dead bodies) singing and strolling in gardens. The latter suggestion may have been intended to put one in the vicinity of plants with medicinal properties to prevent spread of the plague. And as was typical in medieval times when there was a pervasive belief that disease could be a punishment for sinful behavior, medical people advised staying clear of gluttony, excessive drinking and, of course, immoral women.

Galen and Theriac

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about physicians during the time of the plague was, with one notable exception, it did not stir them to consider new causes or solutions. Indeed, there is a fairly direct lineage of medical thought that arose from Galen—a very famous ancient physician from the second century AD—to the time of the Medieval plague. The Galenic tradition persisted after the time of the Black Death as well. The medicines that were available to treat specific conditions such as the plague did not evolve much during the period from the time of Galen to the 19th century. One of the treatments that was used throughout this period, a medicine in which faith was so great it was referred to as the Universal Antidote, is the chemical compound called Theriac.

Galen had a rich and varied history which included serving as a physician to the Gladiator School giving him abundant opportunity to examine and treat trauma victims. Galen also learned a lot about anatomy and physiology, frequently giving public lectures and demonstrations on these subjects. Ultimately, he won renown among the upper crust by correctly treating complex conditions and making his royal patrons better. This netted Galen a position as the personal physician to Marcus Aurelius and several emperors thereafter. While often hailed as modern, especially for his rational approach to medicine and disease, Galen also shows evidence of primitive thinking too. He was a big fan of blood-letting, for instance, as a way to purge unhealthy influences and he, like his contemporaries, believed that health and disease was an issue of balancing the body’s humors.

At the time, the reigning view was that there existed four humors: blood, bile, yellow bile, and phlegm; and that each had specific properties: hot, cold, wet, and dry respectively. Disease occurred if the humors were not properly balanced. Further, disease could be prevented by following a regimen that was directed at maintaining the proper balance. In Galen’s view, it was the physician’s job to prescribe and adjust that regimen, or regimen sanitatis, for the patient in order to keep them healthy.

Physicians of Galen’s time were all good herbalists. They believed that certain plants contained elements that would prevent or treat disease and that the plants themselves showed physical signs of what it would be good for treating. The liverwort, for instance, is so called because if looked at in just the right way, it bears a resemblance to the liver in the human body and was, therefore, prescribed for treating liver ailments like jaundice. Other common herbs or plant-derived treatments came from plants like camphor, rose, and pomegranate. All of these were used to treat the plague at some time in some way. But the most common plague preventative and therapeutant was a mixture called Theriac.

There were a lot of recipes for Theriac, many of which were translated from Arabic, and which might contain as many as 80 ingredients. Most of the ingredients were plant-based palliatives but some recipes included viper skin because it was thought to counteract the poison in a snake bite if given in graduated doses. Other ingredients included ground coral, balsam, pepper, rose water, sage, cinnamon, saffron, ginger, parsley, myrrh, and several ounces of opium. As the descriptor, the Universal Antidote implies, Theriac was used to treat all manner of conditions including the plague. In retrospect, the most important effects were most likely contributed by the opium found in Theriac.

One must ask whether the fantastic claims made about Theriac, claims that persisted for nearly two millennia, were, in fact, true. Could Theriac, for instance, prevent one from getting plague? Realistically, and given what we know from the modern perspective, Theriac could not prevent a person from getting plague. However, there were ingredients that promoted good health and, to the extent that a strong constitution could make it less likely that you’d get the plague, there may have been a small positive effect on prevention provided by Theriac. It would be the sort of effect that kept you safe until you got out of town and away from the pathogen. In other words, Theriac would probably not get you through a plague epidemic all by itself. But one shouldn’t overlook the placebo effect provided by Theriac. People tend to be most vulnerable when they a view a situation as hopeless and that they are unable to do anything to alter what appears to be a set course of action. The administration of Theriac at least gave people a psychological boost and a reason to believe that their own personal fate might be different. There were even medical tracts that identify the body types for which Theriac was likely to be most useful in preventing plague.

Let’s assume a person has already contracted the plague. Could Theriac actually be helpful to that person? For Medieval physicians, the answer was an unequivocal “yes”. In fact, Theriac was described by medieval doctors as being “unsurpassed in its effectiveness,” suggesting that the bar must have been set pretty low. From other times and other diseases, it was believed that Theriac was effective in treating conditions as diverse as nausea, thirst, headache, fever, pain, weakness, and anxiety, which are all conditions that had been reported by people stricken with plague. Of the various effects that were reported with the plague, it is likely that the opium ingredient alone would have lessened symptoms of pain, coughing, and diarrhea. Plus, opium has a sedative effect, which would have been very helpful in getting rest while enduring the ravages of the plague. Some cautions in the use of Theriac to treat plague were noted by physicians who believed in Theriac as a treatment for plague; e.g., it was recommended that Theriac not be applied directly to buboes for fear that it would push the poison contained in the buboes further into the body.

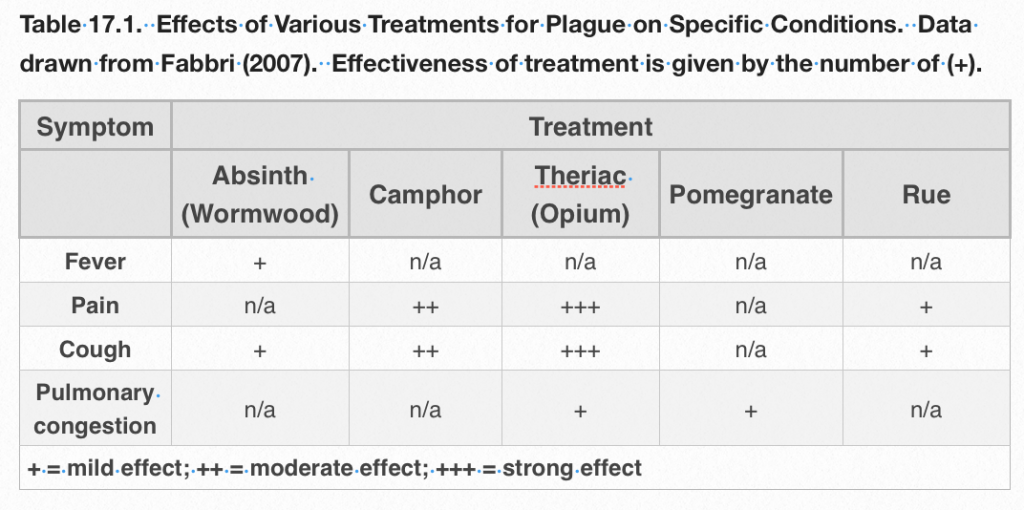

The big question that remains, however, is whether this was just all wishful thinking, or whether treatments such as Theriac actually were effective in plague treatment? The answer is a qualified yes—the treatments were effective. In a recent study, using modern criteria for effectiveness, the authors noted that many of the herbs used by physicians to fight disease actually have identifiable and measurable effects on human physiology. Some of these are summarized in Table 17.1, taken from Fabbri (2013). Here you see the kinds of herbs, many of which would have been found in Theriac, and the physiological effects they have. The number of plus (+) symbols entered for each ingredient is a measure of the effectiveness in treating a particular symptom: the greater the number of plusses, the more effective Theriac is for that malady. Two caveats are important at this point. First, the opium component was undoubtedly the most important component of Theriac for ameliorating symptoms. Second, the therapy provided by Theriac basically treated the symptoms. This, no doubt, lessened some of the distress experienced by plague victims. It certainly would have been a psychological benefit. However, these herbs by themselves probably did little to reverse the course of pandemic plague once a victim had the plague bacterium in his body. Some survived with or without treatment. But, most succumbed to the disease. In other words, should plague strike again today, get an antibiotic—fast. Leave the Theriac for other, less lethal diseases.

Guy de Chauliac

The one bright spot on the medical horizon throughout The Black Death was a medieval physician named Guy de Chauliac. He began his medical training at Toulouse before proceeding on to Montpellier, one of the foremost institutions for medical training at the time. Chauliac wrote a very influential book on surgery, Chirurgia Magna, which became a standard in medieval medicine. As a result of his success, Chauliac came to the attention of Pope Clement VI who invited Chauliac to the Papal Court at Avignon where he became the Pope’s personal physician, a position he held for 10 years. Chauliac stayed on to serve three popes after that.

Like all physicians since the time of Galen, Chauliac was trained to think that disease was an upset in the balance of the body’s humors, something that could be caused by an unusual alignment of planets. At the time of The Black Death, an unusual alignment of Jupiter, Mars, and Saturn had occurred, leading people to believe that this set off the miasma which was the ultimate source of the plague. But, Chauliac had an independent streak that made him stand out among his fellow practitioners. While other physicians were refusing to treat the sick for fear of contracting the plague, Chauliac not only continued to treat them, but also took copious notes, detailed histories and recorded the effectiveness of different treatments. In the process, Chauliac, himself, contracted the plague. Throughout his illness, he took detailed notes about the symptoms. The fact that he nearly died as a result does not seem to have fazed him. He kept treating patients, including the Pope, whom he advised to stay inside the papal residency and surround himself with burning oil.

Despite Chauliac’s comparative modernity, he still thought that miasmas caused the plague and, what better way to fend off a miasma than to light a flame and burn it off? So, the Pope spent the summer in residence with fires burning around him in his chamber. The heat and the smoke must have made it nearly impossible to endure, but the Pope never fell ill with the plague. And Chauliac did make a bit of progress in understanding the progression of the disease and the efficacy of available treatments.

In the 20th century, antibiotics at last became available. And since plague is caused by a bacterium, it is treatable with antibiotics. n modern times, contracting the plague is not a death sentence as long as the person is treated with antibiotics promptly, and as long as our arsenal of antibiotics is not rendered impotent because the bacteria become resistant.

Men of God and the Plague

God was a focal point of medieval life. God was not confined to Sunday but was an everyday concern. It is, perhaps, understandable that appeals to God would be made to escape the plague, or for relief for those who had contracted it; and, at the same time, God was viewed as the likely source of the plague as a punishment for wickedness. Such was the power of the deity even at a time when His creation was visibly stricken with the worst of evils.

The reaction to the plague among the clergy was, perhaps, less noble than one would hope for among those who are here on earth to do God’s work. It is certainly true that many clergy willingly attend the sick and died as a result of their proximity to the illness. At the Pope’s home in Avignon, the number of priests fell from 40 to 7 by the time the plague left Europe in the 14th century. Still, as the plague claimed more victims, the some clergy began to shun their duties for fear of contracting the scourge. In addition to refusing to render last rites, some priests refused to hear confessions. As a substitute, they suggested that men confess to one another. And if that wasn’t possible, they could take the unprecedented step of allowing a woman to hear one’s confession as a last resort.

From the pulpit, one heard that the plague was God’s expression of displeasure with bad behavior on earth. This message was reinforced with the publication of tractates that argued that the plague was a rational reaction of the deity to sinful behavior by mankind. To rid the world of plague, one needed to purge sin of all kinds. Deuteronomy 28 was often cited by preachers to make the case that God promises prosperity to those who keep the faith and the plague to those who do not:

Deuteronomy 28:1-2 (NIV)

1If you fully obey the Lord your God and carefully follow all his commands I give you today, the Lord your God will set you high above all the nations on earth. 2All these blessings will come on you and accompany you if you obey the Lord your God:

There follows here a long list of blessings. Then:

Deuteronomy 28:15, 20-24 (NIV)

15However, if you do not obey the Lord your God and do not carefully follow all his commands and decrees I am giving you today, all these curses will come on you and overtake you.

20The Lord will send on you curses, confusion and rebuke in everything you put your hand to, until you are destroyed and come to sudden ruin because of the evil you have done in forsaking him. 21The Lord will plague you with diseases until he has destroyed you from the land you are entering to possess. 22The Lord will strike you with wasting disease, with fever and inflammation, with scorching heat and drought, with blight and mildew, which will plague you until you perish. 23The sky over your head will be bronze, the ground beneath you iron. 24The Lord will turn the rain of your country into dust and powder; it will come down from the skies until you are destroyed.

Others argued that the plague presaged the End of Times. It was not a hard argument to make. Medieval people expected Christ’s return to be heralded by the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (Famine, Pestilence, War, and Death). With the plague, you got all four. As if any more evidence were needed, many believed that the plague had come to usher in the end of the world.

As the death toll mounted, the populace became increasingly restive. Prayers were not stopping the plague. The clergy themselves were increasingly viewed as ineffective in their ministrations, and the church hierarchy also came under increasing criticism. This was fueled by misbehavior that began at the top. Pope Clement VI was disliked for retaining the papal residence in Avignon in preference to the traditional location in Rome. But, even more egregious were the allegations of abuse of power, and misappropriating of funds. The Pope surrounded himself with opulence even as his parishioners were dying in droves in squalor. Priests were also increasingly held in low esteem as well with allegations of having concubines and engaging in the very behaviors they expected others to forego. The callous refusal of some priests to administer death rites did not help.

In part, these reactions were completely foreseeable. The tide of death that beset society was unstoppable. Even the royal family in England was affected. King Edward III retreated to his country estate along with his eldest son to wait out the plague. But his favorite daughter, Joan of England, was taken by plague en route to marry a Spanish prince. The gentry left cities to escape the plague but the peasants who tended their country estates continued to die in large numbers, as did the poor who had to remain in cities for lack of better options. By 1349, so many people were dying that gravediggers needed to produce 300 graves a day to keep up with the body count in London alone. Similarly, at Avignon where the Pope stubbornly remained in residence, 11,000 people died in a six-week period. In desperation, the Pope consecrated the Rhone River and had the bodies “buried” there since the gravediggers, who were living in wretched conditions and the most likely to contract plague, simply could not keep up. In Italy, mass graves were filled with as many bodies as they could accommodate. The bodies were laid in trenches lasagna-style meaning that a row of bodies would be placed with the heads all pointing in one direction and the next layer would be assembled with the feet at that end.

The Plague in Sienna: An Italian Chronicle

At this point, society itself was unraveling. Having lost faith in the clergy, people turned to other solutions. One was conveniently provided by a group that began its odyssey in Germany. rom the Rhine region of Germany came the flagellants (Figure 17.2 – click on link). They were groups of men who believed that extraordinary penance was required to assuage God’s anger at human sin. Their solution was to try to replicate the suffering of Christ’s passion and, thereby, to expiate the sin which God had delivered to the world in the form of the plague. Hoping to win God’s mercy by purging sin, groups of up to 1,000 men walking two by two and chanting Pater Noster (The Lord’s Prayer) and Ave Maria traveled the countryside. They would commit themselves to a Master who led the procession with a banner made of purple velvet. The procession would move from town to town, stopping in the town square to have a ceremony. Stripped to the waist, each flagellant would beat himself with a leather thong tipped with metal studs, each trying to outdo the others by inflicting the most damage on himself (Figure 17.3). Meanwhile, the Master would circulate and add extra beatings to any member who had dared transgress the group’s rules or who had committed a crime. This would be repeated three times per day for 33 1/3 days, the number of Christ’s years on earth. In the end, the Master would call for mercy to all sinners.

People in the towns who saw the flagellants were rapidly drawn into the flagellants’ zealotry. Standard religion was delivering nothing in terms of protecting them from the plague. Clearly, a more rigorous form of devotion would be required to encourage God to take the plague from mankind. The flagellants provided the perfect model. People watching became enthralled, perhaps, and for the first time they felt as if there was something they could do to protect themselves. Many people smeared themselves with the blood of the flagellants as it dripped from their wounded bodies. Some believed it had miraculous properties. All were uplifted by the presence of the flagellants who seemed to have hit upon a brutal, but effective way to appease God. The people desperately wanted and psychologically required a miracle, and the flagellants seemed equipped to provide one.

People in towns began to take the flagellant message to heart as they tried to actively purge sin among the inhabitants and implement the reforms the flagellants promoted. Citizen groups were formed to monitor and roust sinners. Gambling and prostitution became actionable offenses. Even swearing could land you in jail. Townspeople even prescribed a series of ordinances that regulated treatment of the dead. One even called for the cessation of ringing the funeral bell. There was so much ringing of the bell that it was viewed as creating a source of unnecessary angst.

Then, the flagellants made three mistakes that ultimately led to the demise of the movement. First, encouraged by the reaction of peasants to the movement, the flagellants began to claim that they had the power to forgive sins. This, of course, was a direct affront to the Catholic Church, which believed that only Jesus can forgive sins and that the church is empowered to do so on earth as Christ’s representative. This was so grave that the Pope could not overlook as it threatened to directly usurp his power. Second, and similar to the first mistake, the flagellants claimed to perform miracles. It was claimed, for instance, that a dead baby was revived by the flagellants and that, under the flagellants dictim, a cow was heard to talk. Miracles were the exclusive province of the Catholic Church and this claim also could not be overlooked by the Pope.

The third action that proved problematic for the flagellants is that they believed that, in God’s eyes, the most offensive humans on the planet were the Jews for having crucified Christ. Following this logic, the flagellants decided that God’s favor could be restored by exterminating the Jews. Under their guidance and encouragement, Jews in Germany were rounded up, accused of a variety of offenses (e.g., fouling of water supplies with poisons) and tortured. As is so often the case, people who are tortured will confess to crimes they did not commit. In medieval times, the penalty was death. Similar “confessions” were extracted from Jews in many German cities which begat a wholesale slaughter of people of the Jewish faith. Even Pope Clement pointed out that Jews were dying in numbers equal to non-Jews, so they could not be the source of the plague. But, hysterical people are notoriously immune to logic and the proclamation had no effect. In fact, in 1349 in an event that became known as the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre 2,000 Jews were taken into custody and burned alive. Sadly, this was repeated in 15 other cities in Germany and Switzerland. By the time the plague left Europe, the number of Jews had diminished greatly.

The human need to assign causation to events is so great, that people all over Europe were looking for a reason that the plague had come. Sometimes women, particularly prostitutes or women with loose morals, were blamed. Some were accused of being witches, for which the death penalty could be exacted without much deliberation. Indeed, the idea of witchcraft was alive and well in the 14th century and was even a topic that attracted the attention of Pope John XXII, the second pope ensconced at Avignon and the author of Magic and the Inquisition which was published in 1326. With the later publication of Malleus Maleficarum (literally The Witch Hammer) in the 15th century, the connection between witches and women became quite explicit. We are advised in Malleus Malefacarum, for instance that “when a women is alone, she thinks evil.” Also stated in Malleus Maleficarum were assertions that women were “a foe to friendship, inescapable punishment, a necessary evil.” To think women capable of pure evil was, thus, not a particularly big leap. Another perennial favorite among scapegoats were cats, a great number of which were dispatched by humans for the crime of bringing plague to mankind.

The flagellants started as a movement based on piety. Its members went through a rigorous selection process that assured their commitment to the cause. For instance, new members had to confess all of their sins since the age of seven and then candidates for membership had to flagellate themselves for 33 days. Additionally, each member had to take an extreme vow of poverty, and they had to agree never to bathe, shave, change clothes, or so much as speak to women. Considering how they must have smelled, the latter would not have been a problem. Finally, members were charged a fee to join. Thus, the flagellants were not a group that poor people could populate, an effort to keep undesirable types out of the group. Although the group was started by true believers, all that changed with the attention and approbation the flagellants received. The final thing that led to the end of the flagellant movement is that they began to believe their own press. People hailed them as the great redeemers and the flagellants internalized it as true. They were invincible and also entitled—to money, to wine and to women. What started as a pious movement filled with zealots evolved into a group of louts who displayed exactly the kind of behavior the flagellants were designed to extinguish.

Finally, in October of 1349, Pope Clement ordered the flagellants to disburse. This command was ignored until a militia was sent to out round up the flagellants. The beheading of several flagellant masters was enough to convince the rest of the flagellants to cease and desist. The purgers had themselves been purged.

Sadly, for the long-suffering medieval peasant, the demise of the flagellants also ended one of the few sources of relief that they had. The arrival of the flagellants to a town was a source of celebration. The people who gathered to see the flagellants could work off their fear, grief, and surplus emotion in a collective fashion. In response, the people confessed sin, atoned for wrongs committed and sought forgiveness. The flagellants brought blessed relief from the fear that pervaded every waking moment. Once they disbanded, the old world of fear returned.

Plague and Medieval Governance

To understand the impact of the Black Death on medieval society, it is necessary to contemplate the effect of massive, unexpected death on a global scale. As people became ill, they could no longer work. This meant that activities that required human labor would come to a standstill. Agriculture is an enterprise that requires a huge, ongoing investment of human labor, and even more so during medieval times when we did not have powerful machinery. With the plague, much of that activity would come to a stop once it could no longer be outsourced to those who weren’t sick. Imagine what this would have meant. Crops would stand in the field since workers to harvest the crops were likely suffering from one of three fates: they were sick from the plague; they had died of the plague or they were afraid of contracting the plague and had gone into hiding. If crops weren’t harvested, the food available to feed the survivors would plummet as would income from the sale of the harvest. Either way, economic chaos would result. Livestock such as swine, cattle and sheep must be fed, either by turning them out to pasture, or providing stored food every day. As the labor force diminished, livestock were probably let go to forage for themselves. This solution would also have made cleaning up after animals in the barn or paddock unnecessary and, thus, saved time and effort. But, it was a symptom of a society on the verge of collapse.

To a certain extent, creative redirection of energies could assist in keeping the economy going. Instead of growing livestock which require daily care and maintenance, propertied people could switch to growing a cash crop which required less ongoing effort. The switch was assisted by the economic reality that, in times of shortage, prices paid for the goods that were in short supply go up. Indeed, the price of food increased roughly four-fold as the plague swept across Europe. While this was good for the gentry, it exacerbated the already dire conditions of the peasants who could not afford to pay the highly inflated prices.

Agriculture, of course, was not the only industry affected by the plague. Everything was. So the ripples that, perhaps, began in agriculture spread and magnified as time and the plague went on. Entire towns had been depopulated by the plague either because the inhabitants died or because they fled. Many churches were standing empty both of priests and parishioners. From the dressmaker to the baker to the herbalist, everyone’s ability to ply their trades, make money, and feed themselves was imperiled. And because of the suddenness with which the plague struck, the comprehensiveness of the death it caused, and the ability of the plague to travel rapidly via over-land as well as via water routes, it is no wonder that, to the average peasant, this truly conveyed the notion of the end of the world.

This is not to say that valiant attempts to hold society together were not undertaken. But due to a lack of understanding of the nature of the disease and rigid ideas about social class, the changes made had little ability to address the problems brought by the plague. Prior to the advent of the plague, the labor of peasants was a very cheap commodity. There were lots of peasants and, therefore, their labor could be procured for a very low price. Under the feudal system of government, grants of land were given in return for labor. Of course, the class structure in medieval society insisted on a differential allocation of resources according to one’s rank. The king gave grants of land to noblemen (primarily bishops and barons) of high rank in exchange for a pledge of allegiance, an agreement to ally themselves with the king in political disputes and to help the king field an army in times of war. The noblemen then further subdivided the land among their vassals, a fancy word for servant, who were noblemen of lower ranks and knights. So far, we don’t have a labor force. This was provided by the peasants who were allowed to live on the land held by the nobleman in exchange for their labor, a tiny bit of land, and no vassals. The peasants were the vassals whose labor kept the rest of the food chain going.

Prior to the plague, peasant labor was abundant and, therefore, cheap. After the plague, there were many fewer peasants as the plague had an exaggerated effect on the peasant class and the value of peasant labor soared by 20–40%. This sounds like a win for the peasants. However, parliament passed the Statute of Labourers in 1351, which prevented peasants from seeking higher wages. In addition, prior to the plague, the government raised money by levying taxes on communities. After the plague, and in need of money, this was changed to taxing individuals that had the capacity to bring in more money. A third factor is that, due to the exodus and death of many noblemen during the plague, their estates lay empty. Those of lower rank began to take over the empty estates as a result. It seemed to those traditionally in charge that things were getting out of hand. To combat the perceived chaos, the Sumptuary Laws were passed in 1362 in an attempt to put the peasants back in their place. The new law prescribed the diet of the average peasant and required that clothes be worn of an appropriate quality and a specific color to visually convey the rank of the person wearing them. The noblemen were desperate to stop the infiltration of their rank and privilege by those of lower birth. For a while, at least, the peasants had fate and numbers on their side. They revolted against the new restrictions and forced concessions by the ruling class, for a time at least.

Still, erosion of critical societal functions and necessary services due to the plague caused reconsideration of the entire structure of society. The deficiencies in agricultural production could be made up in part by the fact that the population was significantly lower than it was pre-plague, so less food was needed. The reduction in the peasant labor appears to have spurred human ingenuity to find labor-saving devices, such as the emergence of mills to grind grain and the printing press to mass produce books rather than relying on scribes. In addition, the newly empowered and enterprising peasants may have appropriated for themselves the land of the masters who vacated their estates during the plague. If the masters didn’t return to contest it, the peasants would have had their own land. Instead of paying rent on a hovel, they had houses and an incentive to make a go of it by investing their labor and resources in its success. As a result of being more in control of their own destinies, the peasants ate better and became healthier as a group. In fact, there may have been a fairly profound transition among the peasant class from a largely grain-based diet to one that consisted of generous portions of meat. Modern biologists know that such a dietary shift would have created children with bigger, more active brains. Best of all, these were the first steps in challenging the feudal system that had suppressed the growth and ambition of the peasant class for centuries.

Chapter Summary

An intriguing possibility is that the plague, while it was unquestionably a terrible assault on mankind, may have led, in a roundabout way, to liberation. Before the plague, everyone knew his or her place in society. There was great emphasis on piety, belief in God, and living one’s life in a way that exemplified the virtues of Christ. In short, there was little questioning of the status quo or of the set of beliefs that bound society together. After the plague, the human mind began to question everything. Why is God doing this to us? What purpose does this serve? Every person in medieval society had witnessed or knew of someone who had died from the plague. Why are men of God not able to stop the scourge? Scholars suggest that this newfound liberation of the mind was a necessary predicate and, perhaps, a direct antecedent to the intellectual and artistic flowering that took place in the Renaissance, which began in the late 14th century and extended to the 16th century. It marked the transition from the medieval world to the modern one. The role of the plague in bringing this is a thin silver lining during a period that otherwise stands out as a monument to human misery.

References

Chapter 17 Cover Photo: Dog flea. CC-BY 4.0: Wellcome Images. Accessed via wellcomeimages.org

Figure 17.1: Copper engraving of Doctor Schnabel [i.e Dr. Beak], a plague doctor in seventeenth-century Rome. By Paul Fürst; in book by Eugen Holländer. CC0 Public Domain: Columbina, ad vivum delineavit. Paulus Fürst Excud. Accessed via https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plague_doctor_costume

Figure 17.2: Flagellants marching. Available from Britannica Kids. http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/art-181445/Flagellants-believed-that-the-Black-Death-was-a-punishment-from

Figure 17.3: Self-inflicted damage of flagellants. Jan van Grevenbroeck (1731-1807). Accessed via http://www.art-prints-on-demand.com/a/grevenbroeck-jan-van/aflagellant.html

Table 17.1: Effects of plague remedies. Recreation of Table 1 from Fabbri (2013).

Additional Readings

Fabbri, C.N. (2013). Treating Medieval Plague: The Wonderful Virtues of Theriac. Early Science and Medicine, 12: 247-283.

Fabbri, C.N. (2006). Continuity and Change in Late Medieval Plague Medicine: A Survey of 152 Tracts from 1348-1599. Ph.D. Dissertation, Yale University.

James, T. (2011). Black Death: The Lasting Impact. BBC British History in Depth: Black Death: The Lasting Impact: www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/middle_ages/black_impact_01.shtml.

Kramer, H. and J. Sprenger (1487). Malleus Maleficarum. Translated from the Latin by Rev. Montague Summers, Transcribed by Wicasta Lovelace and Christine Jury. Currently available from Amazon.com.