Chapter 8 – The Lord God, Entomologist

We now turn to the representation of insects in sacred texts. As we have already observed in our discussion of myths, insects are used for two basic reasons: first, aspects of insect biology can be used to explain how the world works; and secondly, we can anthropomorphize insect traits to help us understand and explain human behavior. It is no surprise, then, that insects would figure prominently in sacred texts which share many of the same goals.

Part I: Insects in the Abrahamic Faiths

A 2015 paper by Ron Cherry in American Entomologist argued that gods deal with insects in two basic ways. First, gods use insects as a mechanism for punishing humans for bad behavior. This, of course is consistent with how insects are sometimes used in myths, and is a mechanism that is exhaustingly used by the God of Abraham in sacred texts. If nothing else, this kind of insect reference demonstrates that the God of Abraham was a fairly astute entomologist. Of course, insect-based punishments have been used by other gods in other religions as well, and should not be neglected.

The second major way in which the gods and insects are entwined, according to Cherry, is when humans petition the gods for relief from some entomologically-based disaster. These types of references are numerous. They transcend religious affiliations and are both temporally and geographically diverse. They are also amusing from a modern perspective and deserve mention for all of the aforementioned reasons.

And while both of these phenomena, i.e., punishment for bad behavior and petitioning the gods for relief form insect-based disaster, are true and demonstrable, limiting the discussion to these phenomena would not give a complete picture of the relationship between gods, humans, and insects. A reading of the actual sacred texts in which these references are contained teaches much about the human relationship to the divine as well as our relationship to insects. As a result, this chapter will proceed with a liberal analysis of some of those texts in the hope that the reader will walk away with a sense of the richness, pervasiveness, and antiquity of the relationship between god, man, and insect.

General Considerations

In this chapter, we will investigate the three Abrahamic faiths which are the religions known as Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. All three religions are monotheistic and share a common origin, which is to say adherents of all three faiths worship the same God. Further, all combined, these three religions encompass 95% of Americans who profess a faith. As a result, it makes sense to devote significant time to understanding how insects appear in the sacred texts of these three faiths while recognizing that, of course, there are many other faiths which we could use as examples. We will address Buddhist references to insect life in Part II of this chapter as an example of a world religion that is not primarily practiced in the United States.

As we cover these different religions, there are a few things we would ask you to keep in mind. First, in this chapter, we will be considering three sacred Abrahamic texts: the Bible (both old and new testaments), the Torah, and the Qu’ran. There is significant overlap in these texts as a result of the fact that they have arisen from the same source. For instance, the Old Testament of the Christian Bible includes major parts of the Torah. That is, part of the Torah consists of the first five books of the Old Testament (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Deuteronomy, and Numbers). The Torah also includes parts of Mosaic Law and some oral traditions and therefore is distinctly different from the Bible.

In trying to understand the relationship of these divine tests to biology in general, and entomology in particular, we need to put them in context. The Abrahamic texts were written by people who lived in the Middle East. They are not science texts, although there are attempts to explain natural phenomena in these books. The original texts were written in languages such as Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic—languages that are often difficult to translate accurately into modern English. Difficulties with translation are augmented by other problems, e.g., insects found in the Middle East don’t always have a cognate in North America or Europe, where most translation occurred. And, in books like the Bible, there can be multiple words that refer to the same thing. Ancient people who lived with the insects and the words used to describe them would have an understanding forged by experience. As people in the modern world, we lack a common language and the kinds of experiences that ancient people had with insects. As a result, our language differs from theirs in the richness of terms used to describe insects.

Some additional points of confusion include the fact that there is no single version of any of these texts. Most entomologists who have commented on insects in the Bible have used the King James Version which was first published in 1611. The King James Version of the Bible has been widely used, in part because of the poetic, if a bit archaic, nature of the language. Because the translation was made into English, many English words were used to embellish the text that do not have a direct translation in Hebrew or Aramaic, including words used to describe insects. Further, these types of concerns are exacerbated if one uses one of the more modern versions of the Bible that attempts to bring the English prose into coherence with modern sensibilities. The allusions to insects may appear all the more mysterious even though the language of the more recent translations sounds more like something you would hear in normal conversation.

As an example of the translational difficulties, the word arbeh is used 13 times to refer to a locust and 4 times to refer to a grasshopper. Since biblical scholars in general were not trained entomologists who would know the difference between a locust and a grasshopper, we can’t be sure in modern times precisely what was intended. In addition, there are at least ten different words that might be interpreted as grasshopper, but which seem to refer to other insects entirely, when placed in context in specific texts. Thus, it is inherently difficult to make deductions about which insect is being referenced in many passages. As you can see from Table 8.1, sometimes the word being used to reference a locust (or some other insect) derives from specific root words that specifically means some kind of insect. In other cases, the words used to connote locust derive from an action that locusts might take or a sound that they might make. The richness of the language used is impressive, but it can lead to a certain amount of confusion when translators come along a couple of millennia later to try to make sense of the language in modern times.

Table 8.1: Multiple terms used in the Bible and Torah to describe locusts/grasshoppers

| Hebrew Word | English Translation | Notes |

| arbeh | To increase | From Arabic root “raba” |

| sal’am | To consume | Obselete |

| chargol | Swarm of locusts | Probably from Arabic “charjal” meaning to run to right or left |

| chaghabh | To hide or cover | From Arabic chajab |

| gazam | To cut off | From Arabic jazum |

| yeleq | To lick | From Arabic lsqlaq meaning to dart out the toungue like a serpent |

| chacil | To devour | From Arabic chaucal indicating the crop of a bird |

| gobh | Locust | Possible from obsolete Arabic root gabhah jsba, meaning to come out of a hole |

| gebh | Also from gobh | Can refer to locust or action of locust |

| tselatsal | To ring, to shake | Refers to sounds produced by locusts; onomatopoetic |

We must also deal with some numerical discrepancies. Based on a close reading of the King James Bible, there appear to be about 120 references to insects scattered throughout the Bible. However, after the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls containing original texts of the Hebrew Bible, many changes were made in the English text, including those that refer to insects. In certain cases, allusions to insects were removed from the revised text. Thus, the number of passages with insects in them has been reduced to 98 in the updated version.

Despite the translational difficulties and the recent changes in the text, it is possible to identify specific themes in the ways that insects are used in divine texts. There many references to insects that are descriptive or literal in nature. In contrast, sometimes insects are anthropomorphized and a specific trait of the insect is used to encapsulate or comment upon human behavior, often making some sort of moral point in the process in a manner similar to fables and myths. Finally, one can find insect references that serve a metaphorical purpose in the Bible, with insect references being more numerous in the Old Testament than other divine texts.

Given the similarities between myth and fables and religious texts, it is helpful to also point out some differences. Myths are composed by humans. In contrast, if you are a believer, the Torah or Bible derive their religious authority from divine revelation that was given to human scribes; that is, these religious texts are believed to be the Word of God. Therefore, the prose found in sacred texts is invested with a kind of supernatural authority that is not found, at least in the modern age, among fables and parables. The authority in question is dependent upon one’s status as a believer and investment in a specific religion. This belief is independent of an evidentiary basis supporting that belief.

Insects in the Bible and Torah

Now with the qualifications and restrictions previously mentioned, we are ready to begin with our exploration of insects in divine texts, starting with the Bible and the Torah. Please recognize that not all insects found in the Bible will also be found in the Torah. Specific books and verses of the of the Bible are provided so that the reader can tell which of these books is relevant. The following references are from the the New International Version (NIV), unless otherwise noted as New Living Translation (NLT), the New American Standard Bible (NASB), or the King James Version (KJV).

One of the insects frequently found in the Bible, and usually in unambiguous form, is the ant, for which there are a number of biblical references including the following:

Proverbs 6:6-9

6Go to the ant, you sluggard; consider its ways and be wise! 7It has no commander, no overseer or ruler, 8yet, it stores its provisions in summer and gathers its food at harvest. 9How long will you lie there, you sluggard?

Proverbs 30:24-28

24Four things on earth are small, yet they are extremely wise: 25Ants are creatures of little strength yet they store up their food in the summer; 26Hyraxes [a type of rock badger] are creatures of little power, yet they make their home in the crags; 27locusts have no king, yet they advance together in ranks; 28a lizard [spider in the KJV] can be caught with the hand, yet it is found in kings’ palaces.

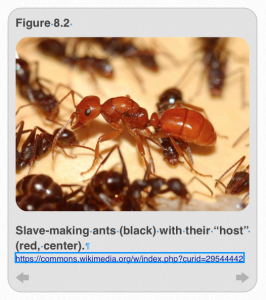

In trying to understand why ants might appear in the Bible, it is useful to know that ants are very common in the area known as Palestine in the Bible. Acknowledging the Species Scape argument presented in Chapter 7, ants would have been seen regularly by common people. Secondly, ants would have been observed collecting and eating a variety of things, e.g., organic debris, plants, and seeds. Some ants even collect and tend aphids for the honey dew production (Figure 8.1). Other ants are called slave-making ants because the worker ants have lost the ability to forage for and feed themselves. Their solution is to pillage the pupae of another species of ant (Figure 8.2). The stolen pupae are raised to adult workers who then proceed to do all of the things necessary to keep the multi-species ant farm going. These are but a few amazing examples of intensely interesting ant behavior that could command human attention.

The intensive gathering activity of virtually all ant species might have inspired the idea of industriousness in human observers as a trait worthy of emulation. The social behavior of ants would have been known in at least a rudimentary form and this may have encouraged analogies to humans, i.e., working hard and saving resources to benefit others would have been viewed as a desirable trait.

The “good” behavior modeled by the anthropomorphized ant is one model of prudence and diligence. Note the similarities between the verses in Proverbs 6:6-9 and the famous Greek fable of the Grasshopper and the Ant. Similar myths/stories that feature the industriousness of ants were featured in Native American cultures, demonstrating that many human cultures and societies recognized these insects’ strong work ethic and drew inspiration from it. Gathering resources when available and storing them for later use is the hallmark of this prudence and the payoff for the ants’ industry. According to the Bible, ants are not sluggards! Many theologies, e.g. Catholicism, regard sloth as one of the seven deadly sins. Thus, humans are encouraged to use the ant as a model of desirable behavior that will pay dividends both in this world and the next.

Another hymenopteran, the honey bee, appears in the Bible in several places and is used in several different ways by its authors. In Deuteronomy and Psalms, honey bees appear as metaphors of aggression as a result of their swarming behavior and ability to string:

Deuteronomy 1:44

The Amorites who lived in those hills came out against you; they chased you like a swarm of bees and beat you down from Seir all the way to Hormah.

To understand the passage, it is helpful to know that the Assyrians (Amorites who lived in Assyria) were long-standing enemies of Israel. In the beginning of this section, Moses is exhorting the Israelites to leave their encampment and enter the territory occupied by the Amorites, an enemy of Israel that God had just defeated so that the Israelites could enter the land safely. Having the Amorites appear in this passage as bees is meant to be a commentary on the ruthlessness of Israel’s enemy. The same applies to the following passage:

Psalms 118:12

They [the enemies] swarmed around me like bees, but they died as quickly as burning thorns; in the name of the Lord I cut them down.

In a related motif, bees are used as the personification of Israel’s enemies:

Isaiah 7:18

In that day, the Lord will whistle for flies from the Nile delta in Egypt and for bees from the land of Assyria.

Here again, Israel’s enemies, the Egyptians and Assyrians, are depicted as insects. In this case, the Egyptians are cast as flies, which is meant to suggest death and decay, thus casting the enemy in an unfavorable light; the Assyrians are represented as bees to drive home the point that the enemies were irascible, truculent people or an enemy to be feared.

For a more positive use of bees in divine scripture, there are many places in the Bible where bees are used descriptively or as a metaphor in which honey production is the vehicle for making a broader point.

For instance:

Judges 14:8

Some time later, when he [Samson] went back to marry her, he turned aside to look at the lion’s carcass, and in it he saw a swarm of bees and some honey.”

The discussion of the lion which Sampson had previously slain appears to be little else than Samson taking notice of what happened to the lion. As a result, this passage is simply a literal description of what Sampson saw and what he was doing without any further, deeper message.

As previously noted, ancient peoples were competent observers of nature and were well aware of the biology of common species. Two passages in Deuteronomy (32:13 and 81:16) show recognition of the tendency of bees to invade cracks or crevices and, once ensconced, to produce honey.

In the Psalms, we learn that honey from the rock is a source of food that will satisfy you:

Psalms 81:16

But you would be fed with the finest of wheat; with honey from the rock I would satisfy you.

One modern use of this reference is the naming of the gospel group Sweet Honey in the Rock.

The Bible is also rich in metaphorical uses of honey. For instance, when Canaan is introduced as the land of milk and honey:

Exodus 3:6-8

6Then He said, “I Am The God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob.” At this, Moses hid his face, because he was afraid to look at God. 7The Lord said, “I have indeed seen the misery of my people in Egypt. I have heard them crying out because of their slave drivers, and I am concerned about their suffering. 8So I have come down to rescue them from the hand of the Egyptians and to bring them up out of that land into a good and spacious land, a land flowing with milk and honey—the home of the Canaanites, Hittites, Amorites, Perizzites, Hivites and Jebusites.”

Continuing on in this vein, honey is associated with good health:

1 Samuel 14: 24-27

24“Now the Israelites were in distress that day, because Saul had bound the people under an oath, saying, “Cursed be any man who eats food before evening comes, before I have avenged myself on my enemies!” So none of the troops tasted food. 25The entire army entered the woods, and there was honey on the ground. 26When they went into the woods, they saw the honey oozing out, yet no one put his hand to his mouth, because they feared the oath. 27But Jonathan had not heard that his father had bound the people with the oath, so he reached out the end of the staff that was in his hand and dipped it into the honeycomb. He raised his hand to his mouth, and his eyes brightened.

Proverbs 24:13 (NLT)

13My child, eat honey, for it is good, and the honeycomb is sweet to the taste. 14In the same way, wisdom is sweet to your soul.

And milk and honey are identified as the sources of sweetness in the beloved:

Song of Songs 4:11

Your lips drop sweetness as the honeycomb, my bride. Milk and honey are under your tongue.

The idea of the sweetness of honey also makes an appearance in Revelations:

Revelation 10:7-11

7“But in the days when the seventh angel is about to sound his trumpet, the mystery of God will be accomplished, just as He announced to His servants the prophets.” 8Then the voice that I had heard from heaven spoke to me once more: “Go, take the scroll that lies open in the hand of the angel who is standing on the sea and on the land.” 9So I went to the angel and asked him to give me the little scroll. He said to me, “Take it and eat it. It will turn your stomach sour, but in your mouth it will be as sweet as honey.” 10I took the little scroll from the angel’s hand and ate it. It tasted as sweet as honey in my mouth, but when I had eaten it, my stomach turned sour. 11Then I was told, “You must prophesy again about many peoples, nations, languages and kings.”

Clearly, honey is meant to connote abundance, prosperity, and even good health in these passages. Other passages in the Bible suggest that honey was important as a food source. For instance, John the Baptist survived on honey during his time in the wilderness:

Matthew 3:1-4

1In those days John The Baptist came, preaching in the Desert of Judea 2and saying, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is near.” 3This is He who was spoken of through the prophet Isaiah: “A voice of one calling in the desert, ‘Prepare the way for The Lord, make straight paths for Him.'” 4John’s clothes were made of camel’s hair, and he had a leather belt around his waist. His food was locusts and wild honey.”

Finally, honey was often given as a gift, all indications that the meaning of honey transcended the literal and held a much deeper meaning in the ancient Middle East:

Genesis 43:11

“Then their father Israel said to them “If it must be, then do this: Put some of the best products of the land in your bags and take them down to the man as a gift—a little balm and a little honey, some spices and myrrh, some pistachio nuts and almonds.”

Elsewhere in the Bible, there are numerous other references to honey in various roles. For example, honey is represented as a food source:

Song of Songs 5:1

I have eaten my honeycomb and my honey.

And the words of the Lord are described as sweet as honey:

Psalms 19:9-10

9The fear of the Lord is pure, enduring forever. The decrees of the Lord are firm, and all of them are righteous. 10They are more precious than gold, than much pure gold; they are sweeter than honey, than honey from the honeycomb.”

Proverbs gives us a very interesting warning against the sin of adultery that involves honey:

Proverbs 5:1-3

1“My son, pay attention to my wisdom, turn your ear to my words of insight, 2that you may maintain discretion and your lips may preserve knowledge. 3For the lips of the adulterous woman drip honey, and her speech is smoother than oil.”

Ezekial provides a prosaic description of honey as a commodity:

Ezekial 27:17

“Judah and Israel traded with you; they exchanged wheat from Minnith and confections, honey, olive oil and balm for your wares.”

Moses (the presumed author of Deuteronomy) does double-duty, both describing honey as a food source and the notion that it can come from a crag in a rock:

Deuteronomy 32:13

“He nourished him with honey from the rock, and with oil from the flinty crag.”

In summary, the Bible verses devoted to bees capture diverse elements of bee biology. The references vary from the swarming behavior and the damage it causes as a metaphor for human aggression. They include the tendency for bees to invade cracks and crevices or even an animal carcass to set up house. They certainly reflect the production of honey and its cherished status in ancient times. Importantly, the references to honey are found both in the Bible and in some of the books of the Bible that are found in the Torah. Allusions to honey, thus, are an important part of Christianity and Judaism.

Elsewhere, stinging insects other than bees are used to convey human ruthlessness, particularly among the enemies of Israel. Similarly, other enemies of Israel are compared to flies, with the intention of suggesting death and decay.

Coming in for honorable mention is another hymenopteran mentioned in the Bible, namely the hornets. Translated from the Hebrew word tsir’ah, which specifically connotes the power to sting, you can get a sense of where this discussion is heading. Tsir’ah is first found in Exodus 23:28, later in Deuteronomy 7:20, and finally in Joshua 24:12. In all cases, the hornets serve as a herding device or, in other words, a way to get undesirable people who are enemies of Israel to move on.

Exodus 23:28

“I will send the hornet ahead of you to drive the Hivites, Canaanites and Hittites out of your way.”

Deuteronomy 7:20

Moreover, the Lord your God will send the hornet among them until even the survivors who hide from you have perished.

Joshua 24:12

I sent the hornet ahead of you, which drove them out before you—also the two Amorite kings. You did not do it with your own sword and bow.

As mentioned above, most authors consider the reference to hornets to be literal, i.e., God will send hornets to clear away the undesirable sorts from the land. However, a few interpreters give these passages a figurative bent, so that hornets represent a more general pestilence. Authors who take this point of view indicate that people both ancient and modern have an acute awareness of the toxicity of wasp venom, an elixir so effective that even those who try to hide will be found out and killed. Some authors use this passage as an indication that God can empower very small, seemingly innocuous things with the power to defeat mighty armies.

Joshua 24:16-18 then gives a recitation of how God kept His word to the Israelites as promised in Exodus to vanquish their enemies and prepare a land of abundance for their use.

Hymenopterans are not the only insects that appear in the Bible. Beetles, although commonly used in other ancient religions (e.g., the Egyptians) are confined to a single citation in the Bible. In Leviticus 11:22, the word “hargol” appears and has been translated as “leaper”, which some scholars consider to be a beetle. The translation has been questioned, however, and most modern scholars consider the passage in Leviticus to be another of the many references to grasshoppers or locusts. In any event, this section of Leviticus tells you that it is permissible to eat them:

Leviticus 11: 22

Of these you may eat any kind of locust, katydid, cricket or grasshopper.

Speaking of locusts (and other orthopterans), the Bible has a lot to say about them. Because of the damage caused by locusts, they naturally figure prominently in the Bible, both in a literal sense and as a metaphorical device. Recall from Table 8.1 that there are 10 different words for locusts in Hebrew again attesting to their importance; although some of the references translated as “locust” may actually be describing other orthopterans. As noted previously, among the first things we learn about locusts is that it is alright to eat them. This is true under Mosaic law and the Old Testament where we learn that, among insects, it is permissible to eat those that “leapeth” but not those that “creepeth”. Thus, the saltatorial hind legs of locusts put them firmly in the “acceptable to eat” category. Indeed, Middle Eastern cuisine, both ancient and modern, uses locusts as a human food source. They can be boiled, roasted, or stewed with butter. Locusts are also identified as good for eating in the New Testament, specifically in the parallel passages about John the Baptist appearing in Matthew 3:4 (already discussed above) and Mark 1:6.

Mark 1:6

John wore clothing made of camel’s hair, with a leather belt around his waist, and he ate locusts and wild honey.

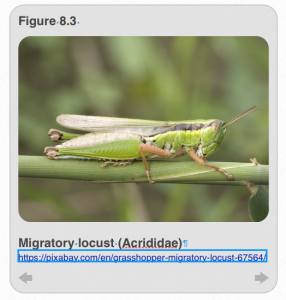

A second very common Biblical reference to locusts stems from their swarming behavior. At this point, it is helpful to discuss what is meant by the term “locust” to a modern entomologist. Locusts are a group of grasshoppers, of which there are many different species (Figure 8.3). Locusts distinguish themselves by periodically forming dense swarms which mobilize and devour crops in their wake. Locusts tend to live in warm places such as India, Africa, and the Middle East. They have a typical hemimetabolous life cycle consisting of an egg which hatches into a series of nymphal stages, and eventually develops into an adult.

When locust populations are low, swarming behavior does not occur and there is little plant damage. However, when populations exceed a critical threshold, the swarming behavior is induced. The insects will form large bands of hundreds of millions of individuals, so many that they can reportedly darken the sky as they move. Moving forward at a rate of a kilometer per day, the locusts can devour significant amounts of plant material over a large geographic area. A swarm of locusts appears in Figure 8.4. Clearly, a person caught in such a swarm might feel as if he is being suffocated by the multitude of quickly-moving insects surrounding him. Even trained entomologists can feel intense fear in the presence of a locust swarm because the sheer number of insects is overwhelming.

Cankerworm is one of the many names for locusts in the Bible. The fact that there are many references and many different names being used to refer to the same thing is not surprising considering the devastation of which locusts are capable. Indeed, locusts appear in many places in the Bible. References to the sheer numbers of locusts and their catholic food preferences are found in the book of Joel.

Joel 1:4 (NASB)

What the gnawing locust has left, the swarming locust has eaten; And what the swarming locust has left, the creeping locust has eaten; And what the creeping locust has left, the stripping locust has eaten.

We also find several references to the massive numbers of locusts during a swarm:

Psalms 109:23

I fade away like an evening shadow; I am shaken off like a locust.

Jeremiah 51:14

The LORD Almighty has sworn by himself: I will surely fill you with troops, as with a swarm of locusts, and they will shout in triumph over you.

Nahum 3:16

You have increased the number of your merchants till they are more numerous than the stars in the sky, but like locusts they strip the land and then fly away.

A second type of biblical reference is to describe the size of the swarms of locusts with the intention of conveying a sense of terror and fear. Not surprisingly, one such reference appears in Exodus as one of the ten plagues that God used in his quest to convince Pharaoh to free the Israelites.

The following passage is clearly a literal or descriptive use of the locust motif:

Exodus 10:15

They [the locusts] covered all the ground until it was black. They devoured all that was left after the hail—everything growing in the fields and the fruit of the tree. Nothing green remained on tree or plant in all the land of Egypt.

Conversely, in Judges, locusts are used metaphorically:

Judges 6:4-5 (NASB)

4So they would camp against them and destroy the produce of the earth as far as Gaza, and leave no sustenance in Israel as well as no sheep, ox, or donkey. 5For they would come up with their livestock and their tents, they would come in like locusts for number, both they and their camels were innumerable; and they came into the land to devastate it.

Here, the “they” probably indicates Midianites, a deduction from the allusion to camels for which the Midianites were renowned. The Midianites were a local tribe that was historically hostile to the Israelites. The camels were probably brought to carry back goods plundered from Israeli cities. The passage conveys the fear that the Israelites felt being surrounded by an enemy that was as numerous as locusts—an equally scary situation.

And later in Judges 7:12 there is another allusion to people of whom the Israelites were not fond as being so numerous as to be uncountable. Again, this type of description is clearly meant to convey a sense of how terrifying and difficult the situation was for the Israelites. It is appropriate because the Midianites lived during the time of Moses and hoped to exterminate the Israelites. Similarly, the Amalekites were a particularly vicious enemy of Israel which, at various times collaborated with the Canaanites and the Moabites and the Midianites in their quest to destroy Israel.

Judges 7:12

The Midianites, the Amalekites and all the other eastern peoples had settled in the valley, thick as locusts. Their camels could no more be counted than the sand on the seashore.

In Jeremiah we learn:

Jeremiah 46:23

“They will chop down her forest” declares the Lord, “dense though it be. They are more numerous than locusts, they cannot be counted.”

The “they” in both sentences is the Chaldean army which, because it was so large, could easily deforest the land. In some translations deforestation is given as necessary to clearing the land to support an agricultural life style and, if so, is not a militaristic reference so much as it is a size reference.

The destructive power of locusts is also documented in literal and metaphorical passages. For instance, in the book of Joel, God sends a massive heretofore unseen plague of locusts to destroy the crops of the Israelites as a punishment for unrepented sin. The invasion of the locusts is as terrifying as it is destructive and Joel recounts both aspects:

Joel 1:2-4

2Hear this, you elders; listen, all who live in the land. Has anything like this ever happened in your days or in the days of your ancestors? 3Tell it to your children, and let your children tell it to their children, and their children to the next generation. 4What the locust swarm has left the great locusts have eaten; what the great locusts have left the young locusts have eaten; what the young locusts have left other locusts have eaten.

All told, virtually all of the Israelites’ crops were destroyed, leaving only meat and seafood as food sources after the locusts have passed. Joel goes on to recount the loss of wine in 1:5 due to destruction of grapes; the eradication of figs in 1:7; and in 1:9-11 chronicles the elimination of various types of grain, and the loss of olives which would have deprived the Israelites of oil. The loss of grain would have also meant that there would be less food for livestock, so even though these animals were not specifically killed, the Israelites would have been deprived of the means of raising more livestock to replace the lost plant-based foods. It was a major crisis. This is as good a description as any drawn from biblical sources of why the invasion of locusts was so terrifying. It could literally deprive an entire population of its food supply for the year.

This section is also interesting because it describes several different types of locusts. In some translations (e.g. New Revised Standard Version), the names are rendered as cutting, swarming, hopping, and destroying locusts. In the translation cited here (NIV), the locusts are referred to only as swarming, great, young, and other. In still another translation, the different locusts are represented as creeping, stripping, and gnawing (NASB). If you refer back to Table 1 and look at the roots of the various kinds of biblical words for locusts, you will see the descriptors mentioned in this paragraph in those word roots. Some biologists suggest that the different names used may, in fact, be a description of several separate invasions of different types of locusts. If this is what actually happened, it would have been even more devastating since it would have meant that crops throughout the entire growing season would have been destroyed rather than limiting the damage to those crops that were growing during a limited period of time, e.g. a few days to a week.

The matter is resolved when Joel exhorts the people to repent, after which God restores the food lost during the invasion of the locusts. Note also that God refers to the locusts as his great army.

Joel 2:25-26

25“I will repay you for the years the locusts have eaten—the great locust and the young locust,the other locusts and the locust swarm—my great army that I sent among you. 26You will have plenty to eat, until you are full, and you will praise the name of the Lord your God,who has worked wonders for you; never again will my people be shamed.”

Locusts also appear in Revelation along with another arthropod, the scorpion:

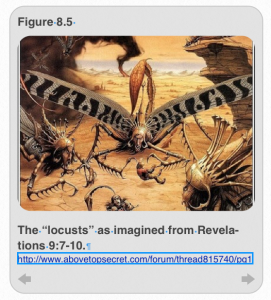

Revelation 9:7-10 (KJV)

7“And the shapes of the locusts were like unto horses prepared unto battle; and on their heads were as it were crowns like gold, and their faces were as the faces of men. 8And they had hair as the hair of women, and their teeth were as the teeth of lions. 9And they had breastplates, as it were breastplates of iron; and the sound of their wings was as the sound of chariots of many horses running to battle. 10And they had tails like unto scorpions, and there were stings in their tails: and their power was to hurt men five months.”

In Figure 8.5, you see an artist’s rendering of the locusts described in Revelations. Note the human faces, the golden crowns and the scorpion tale. Clearly, this is a hybrid arthropod and it is not friendly to humans.

Does the locust appear thus adorned and thus armed because of the cumulative travail they caused throughout the Bible? There can be no doubt that the damage from locusts caused great tribulation leading one medieval pope to excommunicate the locusts in an effort to get rid of them.

Also coming up for frequent mention, and not in a positive context, are flies. They are often used in myths as a sign of death and decay with obvious connections to real life and biology. The biblical references to the fly is also dark, perhaps involving battle or some sort of psychological trial.

For instance, Exodus 8:21-22 refers to a poisonous fly. Here, the Lord is exhorting Pharaoh to let the people of Israel go. And if he doesn’t the Lord vows to send in swarms of flies (for once, no locusts are involved!), but that the Israelites will be protected from this scourge:

Exodus 8:21-22 (KJV)

21Else, if thou wilt not let my people go, behold, I will send swarms of flies upon thee, and upon thy servants, and upon thy people, and into thy houses: and the houses of the Egyptians shall be full of swarms of flies, and also the ground whereon they are. 22And I will sever in that day the land of Goshen, in which my people dwell, that no swarms of flies shall be there; to the end thou mayest know that I am the Lord in the midst of the earth.

This action was later praised and repeated in Psalms 105:31 where the author recounts the actions taken by the Lord on behalf of the chosen people which included the fourth plague consisting of flies. For your amusement, I have included five different translations of this section starting with the 21st Century King James Version:

21st Century King James (KJ21)

He spoke and there came divers sorts of flies and lice in all their borders.

American Standard Version

He spake, and there came swarms of flies, And lice in all their borders.

Amplified Bible, Classic Edition

He spoke, and there came swarms of beetles and flies and mosquitoes and lice in all their borders.

Blue Red and Gold (BRG)

He spake, and there came divers sorts of flies, and lice in all their coasts.

Common English Bible

God spoke, and the insects came—gnats throughout their whole country!

As you can see, the different translations can’t seem to agree on precisely which insect or insects were involved. It might have been multiple species of flies and lice as indicated in the King James Bible or it could have been beetles AND flies AND mosquitoes AND lice as written in the Amplified Bible. Or maybe it was just gnats if the Common English Bible is correct. What a wonderful illustration of problems with retrospective analyses of ancient texts!

Use of flies as a scourge and a punishment for undesired behavior is also found in in Psalms:

Psalms 78:45 (NASB)

“He sent among them swarms of flies which devoured them.”

There has been much speculation as to what the insects were intended, but many of available translations seem to be talking about the common house fly (Musca domestica). In ancient times, sanitation was poor and these flies were likely to have been abundant. Modern work clarifies that they can harbor and spread human pathogens. On the other hand, some authors believe that the blue bottle fly (Calliphora) fits the description. Still others say the passage refers to “diverse flies” which would cover a multitude of possibilities.

Of course, the ultimate insult, or compliment, given to the fly, depending on your point of view, is found in biblical texts in which the fly is referred to as Baalzebub. Historically, this is a name given to the god of the Philistines in 2 Kings 1:2,3, and 16. The literal translation of the name means “fly-lord” and was given to the king because he was able to avert a plague of flies. At one point, in the passage from 2 Kings, Baalzebub, the historical figure, falls out of favor with God because a local official prays to Baalzebub instead of God to find out if he will be healed from an injury. In the Testament of Solomon, a work attributed to King Solomon, Beelzebub appears as the prince of demons and is thought to represent Satan. The text describes how Solomon was enabled to build a temple by commanding demons by means of a magical ring entrusted to him by the Archangel Michael at which point the connection to Satan was explicit. By the time of Jesus, the connection is not equivocal as demonstrated in Matthew 12: 25-28 and paralleled in Mark 3:23 (not shown).

Matthew 12:25-28

25Jesus knew their thoughts and said to them, “Every kingdom divided against itself will be ruined, and every city or household divided against itself will not stand. 26If Satan drives out Satan, he is divided against himself. How then can his kingdom stand? 27And if I drive out demons by Beelzebub, by whom do your people drive them out? So then, they will be your judges. 28But if it is by the Spirit of God that I drive out demons, then the kingdom of God has come upon you.

Other vermin commented upon in the Bible includes lice. Lice (sometimes rendered gnats) appear twice in the Bible, first as a description of the third plague in Exodus 8:16-18 and later in Psalms 105:31 (not shown) taking God for intervening with Pharaoh to secure the release of the Israelites. As already noted, specific translations may reference entirely different insects.

Exodus 8:16 (KJV)

“And the LORD said unto Moses, Say unto Aaron, Stretch out thy rod, and smite the dust of the land, that it may become lice throughout all the land of Egypt.

In this passage, lice were produced miraculously from dust—perhaps a first demonstration of spontaneous generation? As you know, lice are small, disgusting, and high on the list of insects to be avoided. Due to translational difficulties, some authors argue that the insect being described may be gnats or ticks but this seems unlikely.

Finally, another pestiferous taxon finds mention in several places. This would be the moth, from the Hebrew ‘ash meaning to fall away. This appears to be a reference to the ability of moths to invade one’s wardrobe and consume clothes. It is also a metaphorical allusion to weakness or decay. As stated in Job:

Job 4:19

“How much more those who live in houses of clay, whose foundations are in the dust, who are crushed more readily than a moth!”

Also from Job:

Job 13:28

“So man wastes away like something rotten, like a garment eaten by moths.”

Moths also appear in Isaiah where the writer is trying to convey the power of God against his enemies by indicating that they will melt away like a garment eaten by moths:

Isaiah 50:9

“It is the Sovereign Lord who helps me. Who will condemn me? They will all wear out like a garment; the moths will eat them up.”

Moths also appear in the book of Hosea. Once again, moths are used to indicate decay:

Hosea 5:12

“I am like a moth to Ephraim, like rot to the people of Judah.”

Interestingly, the moth is the only lepidopteran described in the Bible; butterflies are absent despite their common occurrence and high visibility in everyday life.

Insects in the Qur’an

We now turn to the third Abrahamic faith, Islam. As we move through this material, we’ll note similarities and differences with the religions we’ve discussed thus far.

Let’s take a few minutes to talk about Islam. As you know, Islam has been in the news a lot for the last two decades and there are many misconceptions and erroneous assumptions about this religion. Islam is the third of the three Abrahamic faiths and its adherents are called Muslims. The name Islam comes from the Arabic root that means “peace” and “submission.” Indeed, peace is the hallmark of Islam, which teaches that one can find peace in one’s life only by submitting to Almighty God (referred to as Allah) in heart, soul, and deed. The same Arabic root gives us the phrase “Salaam alaykum” or “Peace be with you,” the universal Muslim greeting.

The events of September 11, 2001 have cast a very negative light on Islam, but it is very important to remember that the events of 9/11 were perpetrated by a very small minority of people who say they believe in Islam. Most Muslims do not recognize this radical ideology as consistent with the teachings of Islam and reject the violence used by the perpetrators of 9/11 as a means to express their grievances.

The founder and major prophet of Islam is Mohammed, who was born in Mecca in 570 AD. He was similar to Jesus in that Mohammed worked in humble jobs such as being a shepherd and later a clerk. Also like Jesus, Mohammed retreated from humanity at age 25. He entered a cave where he received divine revelations that were written down in the book known as the Qur’an. Mohammed is considered by Muslims to be the last prophet of the Abrahamic God. The others were Adam, Abraham, and Moses, who were the prophets of the Old Testament and Torah. In the eyes of Muslims, Jesus was not the son of God but was a prophet.

Just as the Bible and the Torah have a lot to say about insects, one can also find some comments about insects in the Qur’an; although the representations of insects are not nearly as numerous. And since Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all share a common root, there is considerable overlap in some allusions to insects, particularly those passages that address whether insects are permissible to eat. Other than that, there are only a couple of references to insects in the Qur’an. One of these involves flies.

“If a fly falls into one of your containers (of food or drink), immerse it completely before removing it, for under one if its wings, there is venom and under the other there is the antidote.”

How are we to understand this statement? One possibility is that it is a metaphor. But, more than likely, the passage is meant to be taken literally or possibly, allegorically—having both a metaphorical and literal meaning. Either way, Muslims consider the Qur’an to be prophetic and literally true. As such, considerable research has been devoted to demonstrate the scientific validity of the Qur’an in modern times. The passage above on flies provides one example of this thinking.

For instance, it is clear from much evidence that flies can carry human pathogens. This is why people may become highly agitated if one sees a fly in the house. We also know and detest the fact that houseflies, for instance, can leave ugly black and brown marks on surfaces on which they alight. Entomologists can tell you that these ugly, hard-to-remove marks are due to the flies regurgitating the contents of their stomach onto your kitchen surfaces. Not a pleasant piece of knowledge, but true. And the fact that flies can carry human pathogens around with them as they are busy regurgitating on your kitchen appliances, with which you prepare your food, does nothing to improve their image. However, the suggestion from the Qur’an that there is an antidote under one wing, may be a way to partially ameliorate the disgust attached to flies. Does the antidote that the Qur’an says can be found under the second fly wing having any basis in reality? The discovery of bacteriophages is taken as evidence by some Muslims of the correctness of the Qur’an.

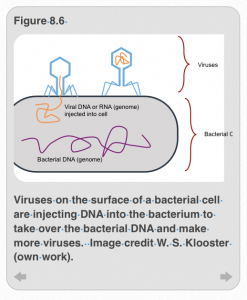

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect bacteria. The viruses amass on the outside of the bacterial cell wall and inject viral DNA into the bacterial cell, just as viruses attack our own cells (Figure 8.6). Thereafter, the viral DNA takes over the bacterial DNA causing it to turn out copies of the virus. The antidote referred to in the Qur’an might, therefore, be a bacteriophage capable of killing or neutralizing the bacterium that would otherwise cause sickness.

Another example of this treatment in the Qur’an is found in a second insect-based quote:

“At length, when they came to a lowly valley of ants, one of the ants said: “O ye ants, get into your habitations, lest Solomon and his hosts break you under foot without knowing it.”

As with the previous quotation from the Qur’an, there has been much commentary about this passage in an attempt to demonstrate its concurrence with what is currently known about science. For instance, the phrase “O ye ants” by one author is thought to represent an alarm pheromone given off by ants in response to an intrusion designed to draw the attention of fellow ants and motivate them to take some sort of action. Further, the defensive pheromone in question is likely to have been produced by glands and is probably an aldehyde or hexanal. It is known that such pheromones cause ants to become agitated.

The phrase “Get into your habitations” is interpreted as an exhortation to the ants to seek safety by going back to the ant hill where they will be protected from further harm. A hexanol-based pheromone is known to increase agitation or movement among ants and is a likely candidate for this job.

“Lest Solomon and his hosts break you (under foot),” according to Muslim commentators on the Qur’an, could refer to a third pheromone. Ants can release a pheromone called undecanone which increases aggression and, according to the authors of this analysis, make the ants ready to face impending danger. What is that danger? Perhaps the approaching human foot that can crush them? It is hard tell from this passage except to acknowledge that all living organisms are fraught with difficulty and have internal mechanisms, usually mediated by the nervous system, to react to danger and help the organism take appropriate steps.

Finally, “without knowing it.” Here, the presence of a fourth chemical, possibly butyloctenol, is adduced. This compound is known to serve as a trail pheromone which when laid down, would assist in leading the ants back to their “habitations” and out of danger. his pheromone also increases the biting behavior of ants and would be useful in neutralizing an enemy.

This passage is typical of what is found about insects in the Qur’an. Muslims often make the argument that Mohammed correctly predicted modern science 1,400 years ago. They will further argue that modern science is verifying the truth set forth in the Qur’an. However, it is also possible that the connections being forged are illusory and largely fanciful. The same is true of attempts to find modern scientific validity in, for instance, Genesis. When taken literally, it requires a tortuous logic to make the Bible mesh with modern science. It is useful to remember that science consists of constructing and testing falsifiable hypotheses. We have yet to hear one drawn from a divine text. This doesn’t make these divine texts any less valuable. It simply means that they are not scientific documents. They ask and answer different questions.

Another source of insect-based wisdom offered in the Qur’an concerns dietary laws, and which insects are permissible to eat. The relationship of these passages to Leviticus in the Old Testament and Torah are very clear, as the rules in all are very similar allowing for translational issues. In both Judaism and Islam, there are specific dietary categories that are used to classify food. In both religions, there are strict rules for preparing food in a way that makes it acceptable. Permissible foods in Judaism are designated “kosher,” while “halal” means acceptable in Islam. In contrast, non-kosher food and haram foods are forbidden in Judaism and Islam, respectively. Clean and unclean foods in Islam are similar to those found in Leviticus and Deuteronomy, suggesting significant knowledge of the Torah by the writer of the Qur’an. Because of the similarities, only the text from the Torah is quoted with differences noted as they occur. As you can see, they are extensive:

Leviticus 11:1-45

“1And the LORD spake unto Moses and to Aaron, saying unto them, 2Speak unto the children of Israel, saying, These are the beasts which ye shall eat among all the beasts that are on the earth. 3Whatsoever parteth the hoof, and is clovenfooted, and cheweth the cud, among the beasts, that shall ye eat. 4Nevertheless these shall ye not eat of them that chew the cud, or of them that divide the hoof: as the camel, because he cheweth the cud, but divideth not the hoof; he is unclean unto you. 5And the coney, because he cheweth the cud, but divideth not the hoof; he is unclean unto you. 6And the hare, because he cheweth the cud, but divideth not the hoof; he is unclean unto you. 7And the swine, though he divide the hoof, and be clovenfooted, yet he cheweth not the cud; he is unclean to you. 8Of their flesh shall ye not eat, and their carcass shall ye not touch; they are unclean to you.

9These shall ye eat of all that are in the waters: whatsoever hath fins and scales in the waters, in the seas, and in the rivers, them shall ye eat. 10And all that have not fins and scales in the seas, and in the rivers, of all that move in the waters, and of any living thing which is in the waters, they shall be an abomination unto you: 11They shall be even an abomination unto you; ye shall not eat of their flesh, but ye shall have their carcases in abomination. 12Whatsoever hath no fins nor scales in the waters, that shall be an abomination unto you.

13And these are they which ye shall have in abomination among the fowls; they shall not be eaten, they are an abomination: the eagle, and the ossifrage, and the ospray, 14And the vulture, and the kite after his kind; 15Every raven after his kind; 16And the owl, and the night hawk, and the cuckow, and the hawk after his kind, 17And the little owl, and the cormorant, and the great owl, 18And the swan, and the pelican, and the gier eagle, 19And the stork, the heron after her kind, and the lapwing, and the bat.

20All fowls that creep, going upon all four, shall be an abomination unto you. 21Yet these may ye eat of every flying creeping thing that goeth upon all four, which have legs above their feet, to leap withal upon the earth; 22Even these of them ye may eat; the locust after his kind, and the bald locust after his kind, and the beetle after his kind, and the grasshopper after his kind. 23But all other flying creeping things, which have four feet, shall be an abomination unto you.

24And for these ye shall be unclean: whosoever toucheth the carcass of them shall be unclean until the even. 25And whosoever beareth ought of the carcass of them shall wash his clothes, and be unclean until the even. 26The carcasses of every beast which divideth the hoof, and is not clovenfooted, nor cheweth the cud, are unclean unto you: every one that toucheth them shall be unclean. 27And whatsoever goeth upon his paws, among all manner of beasts that go on all four, those are unclean unto you: whoso toucheth their carcass shall be unclean until the even. 28And he that beareth the carcass of them shall wash his clothes, and be unclean until the even: they are unclean unto you.

29These also shall be unclean unto you among the creeping things that creep upon the earth; the weasel, and the mouse, and the tortoise after his kind, 30And the ferret, and the chameleon, and the lizard, and the snail, and the mole. 31These are unclean to you among all that creep: whosoever doth touch them, when they be dead, shall be unclean until the even. 32And upon whatsoever any of them, when they are dead, doth fall, it shall be unclean; whether it be any vessel of wood, or raiment, or skin, or sack, whatsoever vessel it be, wherein any work is done, it must be put into water, and it shall be unclean until the even; so it shall be cleansed. 33And every earthen vessel, whereinto any of them falleth, whatsoever is in it shall be unclean; and ye shall break it. 34Of all meat which may be eaten, that on which such water cometh shall be unclean: and all drink that may be drunk in every such vessel shall be unclean. 35And every thing whereupon any part of their carcass falleth shall be unclean; whether it be oven, or ranges for pots, they shall be broken down: for they are unclean, and shall be unclean unto you. 36Nevertheless a fountain or pit, wherein there is plenty of water, shall be clean: but that which toucheth their carcass shall be unclean. 37And if any part of their carcass fall upon any sowing seed which is to be sown, it shall be clean. 38But if any water be put upon the seed, and any part of their carcass fall thereon, it shall be unclean unto you.

39And if any beast, of which ye may eat, die; he that toucheth the carcass thereof shall be unclean until the even. 40And he that eateth of the carcass of it shall wash his clothes, and be unclean until the even: he also that beareth the carcass of it shall wash his clothes, and be unclean until the even.

41And every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth shall be an abomination; it shall not be eaten. 42Whatsoever goeth upon the belly, and whatsoever goeth upon all four, or whatsoever hath more feet among all creeping things that creep upon the earth, them ye shall not eat; for they are an abomination. 43Ye shall not make yourselves abominable with any creeping thing that creepeth, neither shall ye make yourselves unclean with them, that ye should be defiled thereby. 44For I am the LORD your God: ye shall therefore sanctify yourselves, and ye shall be holy; for I am holy: neither shall ye defile yourselves with any manner of creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth. 45For I am the LORD that bringeth you up out of the land of Egypt, to be your God: ye shall therefore be holy, for I am holy.”

In Islam, mothers are expected to breastfeed their children up to 30 months. There is also emphasis on ritualistic fasting. Other dietary laws in Islam share roots in the Old Testament/Torah. You may eat any animals that has a split hoof completely divided and that chews cud (the latter rules out pigs in both Judaism and Islam, but allows followers to eat beef). However, the prohibitions in Judiasm are more extensive including camels, the hyrax (or coney) and the hare. Each is excluded in Judaism because the animal either doesn’t chew its cud, doesn’t have a cloven hoof or both. In Islam, there is more attention to horses and its relatives, e.g. donkeys and mules all of which are haram. This prohibition comes from an unrelated passage in the Qur’an in which these animals are specifically given to mankind for transportation. Since they were not given as a food source, eating them is forbidden or haram.

There are also some differences in Judaism and Islam with respect to seafood, some of which is found in the phylum Arthropoda. Earlier in Leviticus (11:9-12 above) it stated that the Israelites could eat anything that had fins and scales that lived in water. This, of course, rules out shrimp, lobster, crabs and crayfish since they do not have fins and scales, in Judaism. In Islam, the rules seem to be a little more permissive with respect to shellfish whose consumption is allowed.

The advice from later in Leviticus also seems to rule out eating virtually all insects, as in verses 20-23 we learn that virtually all insects are unclean; we are not to eat them. However, an exception is made for orthorpterans but the text is very unclear as to which ones. Some translators take the broad view that any orthopteran with saltatorial hind legs may be eaten. Others restrict the practice to locusts which seems to be consistent with practices of Middle Easter culture. This is particularly the case in Islam where most scholars find locusts to be halal. Technically, it would seem that fleas, too, would be permissible since they do not fly and do have jointed legs for hopping on the ground, although it is difficult to see how one could make much of a meal on fleas. Also, given that they feed on vertebrate blood, they likely do not taste very good and could contain pathogens that would make people sick.

II. Insects in Other World Religions

Buddhism

How are insects treated in other world religions? Buddhism is a good example because it is ancient, dating back to the 5th century BC. Buddhism is also practiced by about half a trillion people making it the fourth largest religion worldwide.

The founder of Buddhism was Siddhartha Guatama, who became known as the Buddha or enlightened one. Guatama lived a life of privilege but left it and entered a period of wandering in the wilderness in search of meaning, a common theme among the founders of world religions.

As a result of his wilderness experience, Buddha enunciated the Four Noble Truths:

- The Truth of suffering,

- The Truth of the cause of suffering (pleasure, material goods, immorality),

- The Truth of the end of suffering (Nirvana), and

- The Truth of the path that leads to the end, i.e., the Eightfold path.

Further, he enunciated the concepts of karma or the idea that what you do in this life carries over into the next and rebirth, i.e., that the current life is just one of many lives for each person. You will be reborn in the future and your karma in the current life will influence how you are reborn.

With respect to insects, explicit references in Buddhism are rare, but questions involving insects and their treatment arise in commentaries on the religion. Among the concepts that are raised with respect to Buddhism and insects are:

• How should we harmonize our beliefs with practices?

• The idea that all animals, including insects, are capable of suffering.

• Since reincarnation is part of Buddhism, it is possible that in a future life, humans of this life might be reborn as insects in the next.

• Therefore, and acknowledging the concept of karma, it is advisable to avoid unnecessary violence towards all animals including insects since they might be relatives.

A variety of stories that involve animals in past lives of the Buddha are told in the Jatakas. If we recall that we are to avoid unnecessary violence even towards nonhuman species, various questions quickly arise. For instance, what happens if I step on an ant? What happens if I accidentally swallow a fly in my drink (other than a certain sense of revulsion)? Can I kill mosquitoes that disturb my sleep and may potentially vector a very harmful disease? In all cases, the Buddhist advice is to avoid the death of the insect if you can. This advice relates to another teaching of the Buddha regarding the release of animals.

In Buddhism, release of captive animals is a demonstration of Buddhist piety. All creatures are on a path to enlightenment and are, therefore under the principle of reincarnation, potential relatives. As a result, we should endeavor to treat even the lowliest creature among us with humaneness since various karmic paths may lead us into community with insects in our next lives. Consistent with this philosophy, Buddhists have constructed ponds to hold fish rejected by fishermen and are known to buy and release animals intended for slaughter.

Buddhism and U.S. Laws

While the average American would not think of our society as demonstrating Buddhist principles, believe it or not, we have a lot of rules governing our relationship to animals in general, and insects in particular, that have a Buddhist flavor. These are not based on divine texts but many of the same considerations go into their creation. For instance, many laws and their attendant regulations that form the basis of their implementation ask a simple question: what is safe for people? Of course, what is safe and healthy for people is likely to be similarly beneficial to other organisms. In that sense, federal laws that govern the quality of the environment have a Buddhist flare to them.

In addition, consider how we treat species that we consider valuable, and adopt and fund practices to achieve sustainability. We seek limits on harvesting critical species so that a viable population can be maintained and future harvests secured. In so doing, we knowingly limit our immediate self-interest to preserve long-term prospects. We may even curtail or outlaw practices that inadvertently do damage to species we are not interested in eating, e.g., dolphins when they are caught in the process of harvesting other species for consumption. In this case we have made the societal decision to not kill a species whose suffering at our hands may be inadvertent but is considered unacceptable collateral damage. We can, therefore, ask the question: Is it possible that secular law has replaced divine injunction even as the purpose has remained similar to prescriptions laid down thousands of years ago in divine texts? It is an intriguing thought to be sure and one that would seem to have a direct lineage to Buddhist precepts.

Another area of U.S. law that appears to have Buddhist undertones are laws and rules governing behavior in state parks. Some of the rules sound similar to ideas in the Buddhist religious canon. For instance, in some cases, it is illegal to hunt, trap, or even possess wildlife, including insects. These injunctions may extend beyond insects that are specifically protected by law, such as those governing endangered species. Restrictions may be placed on collection, e.g., requiring a license or a permit. However, recognizing the legitimacy of making collections for a variety of salutary purposes, exemptions for collections may sometimes be given for educational or research purposes on otherwise protected species.

In the United States, we have a variety of laws governing the release of insects. Many of these are aimed at preventing the release of non-indigenous species which lack predators or parasites in their transplanted home and can therefore cause ecological havoc. But, these rules can also cover non-indigenous insects raised in culture, e.g., silk moths. Recognizing the particular peril caused by the release of alien species, the rules and laws typically do not cover native species.

We also extend protection to species that enjoy protections in other jurisdictions. For instance, we sometimes prohibit possession of insects that were captured (and perhaps killed) contrary to the laws of other jurisdictions. We may also penalize people who engage in illegal trade of these protected species and anyone in the chain of commerce involved in the sale of such species. In short, we may be wise to evaluate our current practices in the context of those that animated our forebears hundreds of years ago. We may find more similarities than we might expect. The bottom line is this: although we typically consider law and public policy to be removed from religious practice, if we look carefully and are somewhat permissive in our interpretation, we can find the roots of various religion’s practices in secular places. Buddhism stands out as a good example.

III. Insectotheology

How the Wisdom of God is Revealed in Creation

We’ve been focusing on how and why insects regularly appear in divine texts like the Bible. It is a rich and storied approach to understanding mankind that has not been neglected by world religious of all types. From time to time, there have also been attempts to use insects to demonstrate the existence of God. This approach to understanding insects, humanity, and the world is called Insect Theology or Insectotheology depending on the translation.

The general idea of looking at nature as a way to understand the mind of God and to praise the deity emerged during the historical period known as the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment was a period of great optimism that occurred between the 17th and 18th centuries, during which time it was believed the capabilities of the human mind would be sufficient to solve the problems of mankind. By employing secular knowledge, humans themselves would assure human rights and set a course for human progress. It was, in the words of E.O. Wilson, “an Icarian flight of the mind . . .” Wilson’s metaphor is rich in meaning. It was at once a grand escape from the bounds of thought that had tethered the human mind to rigid modes of thinking that did not permit much creativity and had no direct impact on human progress. Certainly, there was little thought of unifying knowledge in consilience prior to the Enlightenment. But it was also a dangerous expedition into the unknown. Would the Enlightenment truly bring the intellect of mankind in league with his creative genius and his desire to see humanity prosper from its own initiatives, or was it a fool’s errand that would allow us to briefly soar under the delusion of freedom only to bring us crashing to earth as a result of our own hubris? The results, I would say, are mixed.

During the Enlightenment, the idea that the existence of God could be proved by showing evidence of design in nature came into full flower (pun intended). In other words, the majesty of God could be demonstrated by the complexity, regularity and perfection of the natural world, which constituted irrefutable evidence of the genius and charity of God. The figure best known for advancing this argument both during the Enlightenment and today is William Paley (Figure 8.7).

William Paley was an 18th century clergyman who, by today’s standards, would have been considered quite a liberal thinker. He wrote extensively, and among other positions, defended the right of the poor to steal in support of their families, supported the idea of a graduated income tax in which the rich paid higher rates, argued vociferously for the abolition of slavery, and supported the idea that women should be allowed to work outside the home. He even supported the American colonies during the revolutionary war because he thought it would lead to the end of slavery.

Paley wrote widely and was well published during his lifetime. His first book was The Principals of Moral and Political Philosophy which Paley wrote at the urging of Bishop Edmund Law and his son, John Law. The book became quite influential, so much so, that the book was made a part of the college exams at the University of Cambridge in 1785. This was a rare honor given only to ideas and books that were thought to be truly consequential.

Although Paley was a renowned and respected intellectual, he did not progress through the church hierarchy because of his liberal views. However, his fortunes changed somewhat after the publication of his book on natural theology in 1802, the full title of which was Natural Theology or Evidence of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity. This book became very popular and was widely read, including by Charles Darwin aboard the H.M.S. Beagle. In Natural Theology, Paley adduced lawyer-like evidence to support the contention that the wisdom of the creator was revealed in nature. Two centuries later, the logic of Paley has been appropriated by the modern creationist movement, re-branded as Intelligent Design, to make the same argument today. One of Paley’s analogies has been particularly widely used in the two centuries of Natural Theology’s existence. Specifically, Paley argued that if one found a watch lying on the ground, one would not suppose that the watch came about spontaneously or was created from random forces. Rather, one would see clear evidence in the design and complexity of the watch that the watch was purposefully created by a higher intelligence. Similarly, according to Paley, the design and complexity of nature is evidence of God’s purpose. The watch analogy is still widely used, although often unattributed, by many people today.

While Paley is the historical figure most identified with natural theology, another figure, Friedrich Christian Lesser (Figure 8.8a), published a similar book but was focused on insects as evidence of God’s providence (Figure 8.8b). Moreover, the book was published 60 years before Paley published Natural Theology.

In 1740, Lesser published a volume in German, the English translation for which is Insecto-Theology: Or a Demonstration of the Being and Perfections of God, from a consideration of the Structure and Economy of Insects. It is yet another book for which the title is nearly a complete sentence.

Very little is known about Lesser except that he was a clergy man who was also the son of a pastor, Jacob Lesser. The sparse record of Lesser’s life and accomplishments indicates that he studied Evangelical Theology at the Universities of Halle and Leipzig. Beyond that, Lesser is an obscure figure.

Indeed, if it were not for the efforts of others, Lesser might have been entirely lost to history. Lesser’s book was read by a polymath named Pierre Lynonnet (Figure 8.9) who, among other things, was an accomplished illustrator. Lyonnet took it upon himself to illustrate Lesser’s book, and he also translated Lesser’s book from German into French. Ironically, Lyonnet kept up an active correspondence with Carl von Linné (more commonly known as Carl [or Carolus] Linnaeus), the Swedish botanist who more or less invented the binomial taxonomic system that is still used today. The correspondence with Linnaeus may have been very important in correcting some of the numerous inaccuracies in Lesser’s text.

Lyonnet, himself, had a very interesting personal history. His grandfather left France during the reformation for Switzerland because Catholicism was still strong in France and the Lyonnet family had abandoned it for the “reformed religion.” Prior to his exodus, the elder Lyonnet’s property was taken, and his wife and children murdered. Once in Switzerland, he remarried and his new wife gave birth to Benjamin Lyonnet, the father of Pierre.

Pierre Lyonnet’s skills as an illustrator and engraver were used by a number of authors to illustrate their texts. In the forward to Lesser’s book, Lyonnet relates that he made extensive corrections to Lesser’s text because Lesser had repeatedly gotten the biology wrong. These corrections are published in lengthy notes at the end of Lesser’s book. In fact, the corrections rival Lesser’s writing in length.

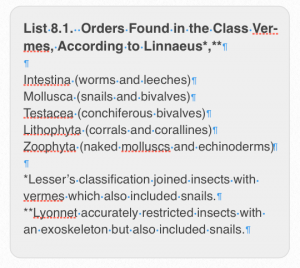

There are also some interesting historical and scientific aspects to Lesser’s book that deserve mention. For instance, Lesser’s book was published at a time when the classification of living things was in flux. Carl Linnaeus was actively developing the binomial taxonomic system for which he would later become famous. He was also actively and repeatedly revising the classifications. Linnaeus, at the time of Lesser’s writing, used the class Vermes (which we would call worms today) for all non-arthropod invertebrate animals. The class was subdivided into several orders which are identified in List 8.1 using modern classification. Lesser, unfortunately, put insects into the same group as vermes, an inaccuracy that Lyonnet tried to fix. However, Lyonnet created his own inaccuracies, judged by modern standards, by including snails, which belong to Phylum Mollusca, in the same group as insects. The inaccuracies, from Linnaeus to Lyonnet, however, do not detract from the central argument being made.

Lesser, like Paley 60 years later, wanted to use the design and complexity of nature to demonstrate the reality of God. In all likelihood, both Lesser and Paley drew heavily upon a third author, Cambridge clergyman John Ray (Figure 8.10), whose 1691 book was titled The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of Creation. Indeed, Paley is routinely identified as the progenitor of the Natural Theology school of thought. Certainly, both Lesser’s and Paley’s books have roots in Ray’s work, which was said to have been plagiarized extensively by Paley in Natural Theology of 1802.

How do we know that God is revealed in insects (broadly and erroneously defined by Lesser)? Because Lesser says so. On page one of Lesser’s book, he lays the argument out for us:

“The vilest insect is the work of omnipotence, worthy of the highest admiration. It is endowed with so many perfections, that the most powerful monarch, or the most skillful artists, can produce nothing to be compared with it. God alone can work those wonders, and he presents them to us, not as models for our imitation, but as so many testamonies of its power and wisdom.”

In other words, God does not hide from us. To the contrary, he has adorned the planet with creatures both mysterious and miraculous, contemplation of which should bring us to reverence for His handiwork.

Lesser continues:

“It is our duty, therefore, to correspond to his views and to contemplate his perfections, even in the smallest of his works.” Here we learn several new things about our relationship both to God and his creation. We are instructed to take heed, to purposefully study nature that we may appreciate the majesty of the Creator. In addition, we are not to neglect the small things or things that we consider vile or disgusting. They are all given to us by the Creator to inspire wonder at His providence.

But, Lesser asks, why focus on insects? Why not focus on things with which we are more likely to agree are wonderful? Lesser tells us that insects are subject to the general law of nature. And what is this law of nature? One law is that insects have to reproduce, and the observer is, therefore, bidden to ask whether insects arise as a consequence of their own power or whether some other force is responsible for insect reproduction.

Lesser notes:

“Upon receiving existence, they [insects] at the same time, received the power of producing their like, and of preserving in this manner, their species for ages. The same God who created them by his power, blessed them, and ordered them to encrease [sic] and multiply each after its kind.”

Here, Lesser argues the fact that insects can be construed as having been mentioned in Genesis 1:24 and commanded, therefore, to be fruitful and multiply. This is evidence enough that God himself is the force behind the reproductive capacity of insects. Therefore, the reproductive capacity of insects, consistent with Lesser’s argument, should cause us to reflect and praise the glory of God.

Lesser even takes on the issue of Spontaneous Generation, a scientific controversy of the time. Scientists were conflicted about whether organisms such as flies could spontaneously reproduce themselves or whether two sexes are required, as in the case of mammals. Many thought that the fact that flies would emerge from a piece of meat left out in the kitchen after a couple of days was proof that flies (and other organisms) could arise spontaneously from different media. Lesser showed a learned grasp of the controversy:

“Observers of nature having remarked swarms of insects in different substances, imagined that those diminutive animals, were produced immediately without the concourse of any animals of their own species.”

Lesser was also well-acquainted with the resolution of this question of spontaneous generation:

“The moderns, better observers than the antients [sic], at last arrived at the truth. They found that insects only grow in such substances, when others of the same species have previously deposited their ova in them.”