Chapter 7 – Insects in Myth

Insects have been fodder for human myths as long as we have been telling and writing them. As such, there simply isn’t a better way to start a discussion of how insects have been used by humans than to examine the topic of insects in mythology. To get started, we will discuss the idea of myth in some general terms and connect the idea of myth to biology through the so-called Species Scape concept. Then, we will look at some native American myths that use insects before moving on to a look at insects in myths, fables, and parables found in Western literature.

As we go through this material, please think about why insects appear in myths. What are they supposed to represent? Throughout this chapter, you will be asked to come up with your own ideas about why we see insects in the places that they appear. The idea behind offloading some of the work to you, the reader, is to stimulate your curiosity and to get you to start thinking more about insects as a source of wonder as well as a source of explanation for the natural world. As you read on, you will see that insects have been important indicators of human desires, fears, ideas about beauty, and an endless source of self-expression for people.

Let us begin with some basics: what precisely is a myth? Many of you have studied Greek mythology and are familiar with the idea from that experience. At this point, the reader workload begins. What is your definition of myth? What is the purpose you assign to a myth? Your answers to these questions will color how you view the role of insects in myth. Think about your definition of myth and its purpose as we move through the chapter. Your definition may be ratified or it may be challenged and expanded. In any event, we will revisit these questions later in the chapter.

Because this is a science book, we will use the species scape concept as a way of understanding why insects appear in myth. Figure 7.1 encapsulates the species-scape idea. There, you see the major types of organisms on earth. They include everything from microbes and fungi to the more familiar mammals and trees. The most important thing about this figure is that the size of the organism is proportional to the number of species in that group. This way of representing organisms upends our normal expectations about the world. When counted using number of species, a familiar group such as mammals is actually among the least abundant and, in this case, is represented by the tiny little reindeer on top of the hill in the middle of the picture. In contrast, a relatively inconspicuous group such as bacteria, whose representatives are microscopic, appear in a size that is vastly larger than their actual size because they are so common. In Figure 7.1, the likely candidate for bacteria appears as a big single cell in the water although they are not necessarily aquatic. Insects are represented by the huge, scary-looking fly that dwarfs all other organisms, owing to insect’s sheer abundance and diversity on the planet. This helps to explain why insects are commonly used in myth. That is, because insects are so abundant, humans paid attention to them and their habits. The result is that insects appear frequently in myth.

As a result of the facts that insects are numerous, often live in close proximity to humans, and are frequently the source of human problems, insects have been popular subjects for myths among humans.

Hopi Butterfly Myths

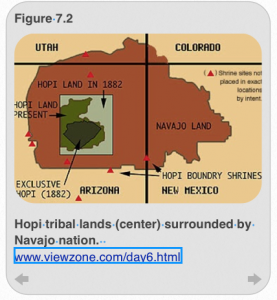

The Hopi Indians live in the American southwest in an area we would now call the state of Arizona (Figure 7.2). Note that the relatively small area occupied by the Hopi is dwarfed by territory held by the Navajo that surrounds the Hopi tribal area and extends into Utah, Colorado and New Mexico.

The Hopi have a rich history of using insects in their myths and, thus, stand out as examples of how insects explain the ways in which the world works. Let’s look at several examples from Hopi lore. Hopi’s share, with many other cultures, a reverence for butterflies. Indeed, in Hopi lore, butterflies adorn all sorts of artifacts including pottery and sand drawings. Reader workload alert: What characteristics of butterflies might make them worthy of appearance in a myth? Come up with an idea or two before continuing on.

Among the most obvious tributes of the Hopi to the butterfly, we have the the Hopi Butterfly Dance and ceremony—a visible testimonial to the importance of butterflies to Hopi culture. The dances are performed in public by both men and women. The Hopi make large tablets emblazoned with butterflies, as well as clouds and other symbols, which they wear on their heads. The dances are extensive, beginning before noon and lasting until sundown, and just like Western operas, there are intermissions, set changes, and costume changes. The basic idea behind the dance is to petition the gods for a good crop. Why might butterflies play this role? Come up with a couple of reasons that the Hopi might believe that butterflies would be good emissaries for getting messages to the gods.

The Hopis also use butterflies in a specific myth. In this myth, the Creator felt sorry for Hopi children because he knows that each child will grow old, their bodies will weaken and grow wrinkled. Eventually, each one will die. In order to prevent despair, the Creator gathered beautiful colors together and put them in a magical bag which he gave to the children. When the bag was opened, the colors emerged as beautiful butterflies which flew out to the delight of the children. The butterflies also sang beautiful songs.

But the story does not end there. The songbirds lodged a protest with the creator. They were miffed that the butterflies were both beautiful and could sing. Beautiful songs, after all, were the province of the song birds! So, the Creator relented and took away song from the butterflies. And this, according to the Hopi, is why butterflies are silent but beautifully colored. In your view, what is the purpose of this myth?

The Hopi butterfly myth is actually very complicated and has a lot of explanatory power. Perhaps you came up with several ways in which the Hopi butterfly myth imparted important life lessons to the Hopi people. How many things did the Hopi butterfly myth explain? Here is the list we came up with:

• Why butterflies are beautiful.

• Why butterflies don’t make sound.

• How the creator compensates for life’s tribulations.

• The relationship between humans and the Creator.

All of these things are all the province of myth.

Indigenous people are generally close to nature and actively seek ways to understand the world. This motivation is very evident in the Hopi butterfly myth. At the level of a child, the myth addressed two physical realities of the real world: why are butterflies beautiful and why butterflies don’t make sound. Explanation of natural phenomena is a common role of myth. But the Hopi butterfly myth goes well beyond providing an explanation of butterfly colors and their inability to produce sound (that we can hear at least). The myth goes on to acknowledge the reality the humans are not immortal and will eventually grow old and die. We all know that this is true and, for humans, it is source of existential dread. But, among the Hopi, the butterfly myth reassures those who believe because the Creator has given the gift of the butterfly to delight us while on earth in recognition of the sadness that attends old age. Thus, Hopi children grow up believing that they are being cared for by a wise and loving Creator who understands their sorrow at having to leave this world one day.

Now, please consider which characteristics of butterflies make them useful for myths? These might be physical traits, behavioral, or some other component of their biology. The ideas we came up with are as follows:

• Beauty—this was the issue that drove the butterfly myth. The myth provides an explanation for its appearance in butterflies and connects beauty to the idea of providing solace.

• Power of flight—another Hopi myth says that butterflies bring dreams in sleep and that butterflies can serve as intercessors between humans and the gods. Both of these are traits that would strongly commend butterflies to the purpose of myth.

• Complete metamorphosis—while this is not a consideration in the myth recounted above, it is acknowledged in another Hopi myth, in which butterflies were able to cheat death by changing form. Indeed, the idea of metamorphosis is used widely in myth and also in divine texts where insects appear as examples.

Hopi Kachina Dolls

The Hopi people use Kachina dolls to represent the personification of benevolent spirits. The Kachina doll is the manifestation of that spirit on earth, but the spirit of the Kachina has returned to the Hopi underworld. If a Hopi wears a costume of a Kachina, it is believed that the person wearing the Kachina costume accrues the characteristics of the spirit the doll embodies.

Because butterflies can fly, it is believed that butterflies can carry messages to the gods and answers back from them. However, the Kachinas are not gods, they merely ferry messages back and forth. The Kachinas have a specific role and religious significance.

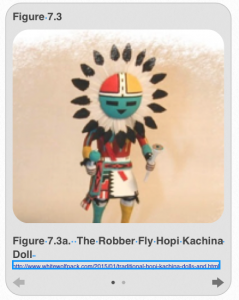

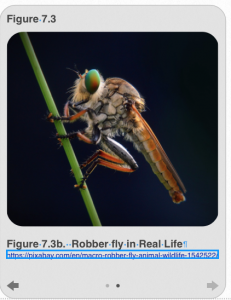

One of the best known Kachinas is also represented by an insect, in this case, the robber fly. You see a Hopi representation of the robber fly in Figure 7.3a. And Figure 7.3b is a picture of the real insect. What physical characteristics of the fly would you expect to be reflected in a myth?

The robber fly has many physical characteristics that can be used metaphorically in a myth or Kachina doll. You may not have an intimate knowledge of robber flies, but Figure 7.3b. shows you that they have a prominent hump on the thorax. That is quite visible in most Kachina dolls. The Hopi are very well acquainted with robber fly biology and would know, for instance, that robber flies are predatory and have a specific behavior of lying in wait for prey. Further, many robber flies feed on blood. Finally, robber flies always seem to be mating, at least it appears so to humans. All of these traits are potentially usable in a myth to teach some element of nature, or a lesson of some kind.

The robber fly is just one Kachina spirit. Figures 7.4a-c shows several other Hopi Kachina dolls—two of which are butterflies and the third a cricket. Wasps and bees are also found in Kachina dolls. Thus, between the robber fly, butterflies, crickets, wasps, and bees, at least four Orders of insects have been represented in Kachina dolls by the Hopi.

The impressive thing is that each of these insects has different biological and behavioral characteristics associated with them. But, the Hopi are pretty good biologists and paid detailed attention to the kinds of traits possessed by insects that could be rendered into myth.

Navajo Dry Paintings

As previously mentioned, the Navajo nation surrounds the Hopi land (refer back to Figure 7.2). As might be expected, the Navaho share the Hopi’s reverence for using insects as ceremonial figure and in myths. For instance, the Navajo use an art form known as dry paintings as part of their ritualized ceremonies designed to combat disease and misfortune. The dry paintings are not just composed of sand, but consist of some sand, ash, pollen, and a host of other dry materials. The Navajo use five colors in their paintings, and they are quite large, i.e., 10-12 feet. In the process of conducting the ceremony, the paintings are destroyed.

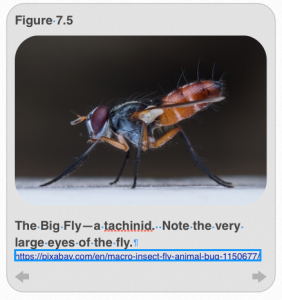

The ceremonies are themselves quite complex, lasting 3-9 days and featuring up to 576 songs, of which several individuals each know only a part. Insects are well-represented in the dry paintings. One insect that occurs frequently in sand paintings is the Big Fly, known to entomologists as a member of the family Tachinidae (Figure 7.5). The Big Fly often appears in sand paintings as a guardian as well as in paintings of Wind and Hail chants. The Navajo believe that the power of the Big Fly is greater than that of all of the gods, a fact that makes the Big Fly a very oft-used figure in sand paintings.

The Big Fly has a well-documented history with the Navajo people and frequently appears in Navajo myths where he is viewed both as an instructor and helper. Like the butterfly in Hopi culture, Big Fly mediates between humans and the deities. The Navajo have shown a keen grasp of tachinid biology in its use as an intercessor for human desires.

For instance, tachinids possess a flight apparatus that is very well adapted for aerial movement which includes large flight muscles, halteres to balance the fly during flight, a mobile head with large compound eyes on both sides, and short antennae to reduce drag during flight. Why would the Navajo be interested in using a fly with strong flight capabilities in their dry paintings and what role is the fly playing in Navajo life? In addition, the Big Fly has an odd behavior of alighting on the shoulder or chest of humans. This is given to mean that the fly can help to guide humans and warn them of danger. Big Fly, thus, became a messenger to humans from the gods to help keep them safe.

Here you see another common subject in Navajo sand paintings: the dragonfly; revered because it symbolizes clean water (Figure 7.6). Why might this be so? What physical or biological characteristics of dragonflies might have commended them for such roles in Navajo myths? The Navajo showed a great fondness for using insects in their ceremonial rites. In addition to the Big Fly and dragonflies, they also use butterflies, bees, other flies, cicadas, spiders, and hornworms (caterpillars of sphinx moths). The Navajo, thus, appear to have a good understanding of the Species Scape concept.

Navajo Myths

One of the actual insect myths written by the Navajos is the Butterfly/Moth myth, which involves a bisexual god named Begochidi. Begochidi was the leader of the butterfly people. Begochidi served the sexual needs of both men and women but, at one point in the narrative, leaves the country. With Begochidi no longer there, the butterfly people had to choose other sexual partners, but they decided to commit incest rather than consort with outsiders. As a consequence of all that inbreeding, the butterfly people went wild and rushed into flames.

From our modern, 21st century perspective, what do you think motivated this myth? The simple answer is fear. The Navajo people, like most cultures, were afraid of incest. But they were also afraid of outsiders. The myth seeks to explain, on the one hand, the biological fact that moths are inexplicably drawn to a flame, which will kill them; and on the other hand, the myth tries to explain why incest should be prohibited. What characteristics of insects are important to the story line this myth?

The myth uses the bizarre tendency of moths to fly into flames as a metaphor for what happens if humans engage in incest. It is a great example of using insects to explain natural phenomena.

Like most cultures, the Navajo have a creation myth describing how the world came into being. Unlike other cultures, insects figure prominently in this myth, as does a large cast of characters and several worlds. The condensed version of the Navajo creation myth goes as follows:

In the first world, taking place on a small ocean island, there were a bunch of insect people, including dragonflies, red ants, black ants, red beetles, black beetles, white-faced beetles, hard beetles, yellow beetles, dung beetles, cicadas, white cicadas, and a non-insect, the bat. Yes, the Navajo have clearly embraced the Species Scape concept! The naughty insect people committed adultery which we already know is a no-no, and this got the insect people kicked out of the first world. To facilitate the expulsion, the gods sent water to drive them out but the insects flew around in circles until the cliff swallows (probably in search of a sustainable food source) led them through a hole in the sky into the second world.

In the second world, there were a bunch of swallow people who lived in mud houses. An insect (we are not told which one) made “too free” with the wife of the swallow people, causing the insects to get booted out of world number two. This time, the wind told the insect people where to find a slit in the sky through which they exited world two and entered world three. Here, there lived the grasshopper people, which was a promising start since they were all insects. But the unrepentant insect people have not yet learned to control their randy behavior and were once again expelled from the 3rd world, moving now into world four.

In the fourth world, the insect people go into rehab when the gods visited and performed a ceremony to create humans from ears of corn. But the men and women argued, had unnatural sex acts (are you detecting a theme here?) and displeased the visiting deities. The latter send a wall of water to send a firm message that sexual impropriety would not be tolerated. This would be the end of the story, but the people found shelter inside a large reed, inside in which they waited out the deluge.

Now we progress to world five which was inhabited by grebes. The Cicadas were permitted to stay in world five if they could survive a challenge, namely, having arrows plunged into their hearts. They survived and the remnant of their survival test is the holes in their sides that we now call spiracles. While there are a lot of dangling plot lines in this story, it does nicely illustrate the importance of insects to indigenous people in their quest to understand the world. It is also a very engaging and fanciful way to understand how spiracles came into being.

Greek Mythology

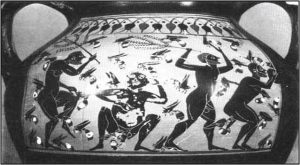

Since many of you grew up familiar with tales of Thor and Loki, Odysseus, and the Trojan War (e.g. Edith Hamilton’s Mythology), we would be remiss if we did not acknowledge the role that insects and other arthropods played in Greek mythology, a subject with which some of you are familiar. Like the Hopi and the Navajo, the Greeks were fond of depicting their relationship with insects in art, literature, and pottery. A Greek vase with an entomological theme, for instance, shows a bunch of naked men being stung by bees. On the same vase, another naked man is playing a flute while expelling sperm and enjoying the company of a dancing woman. There is a butterfly in the background, hence its relevance to us.

Greek mythology is rich in allusions to insects and other arthropods. Sometimes, the insect (or in this case the spider) is the main character. In the Arachne myth, for instance, the mortal Arachne is an excellent weaver, who has the audacity to challenge Athena, goddess of the hearth, to a weaving contest. Cue the dark background music. We know this will not turn out well. Arachne bests Athena at weaving but, like all the Greek gods, the infuriated Athena takes it personally and turns Arachne into a spider. Your job, now, is to figure out which biological phenomenon this myth explains (easy) and what human traits the Arachne myth is meant to illustrate. You should be able to come up with a trait that afflicts Athena and another that characterizes Arachne.

Another Greek myth with an insect theme is that of Myiagros—a minor god whose function was to chase away flies from sacrifices offered to Zeus and Athena. The Myiagros myth now intersects with a more famous myth, that of Bellerophon. Bellerophon is a mortal who wanted to visit Mt. Olympus, which, gods being the egomaniacal types that they were, was unlikely to be well received. Indeed, when Bellerophon appropriated Pegasus, the winged horse, as his ticket to Mt. Olympus, the ever-vindictive Zeus dispatched Myiagros to bite Pegasus causing him to buck and rear, thereby ejecting Bellerophon causing him to fall back to earth. Lesson learned. What characteristic of the insect was useful in this myth and what human trait did this myth deal with?

Fables

Of course, myth is only one of several forms of instructional story used to define human mores and guide human behavior. The fable is another form which differs from myth in key characteristics. The fable is a succinct story (as myths can also be) rendered into prose or verse. The fable uses animals, plants, or inanimate objects in which the object assumes human characteristics or is anthropomorphized. Most importantly, the fable is used to teach a moral lesson. The fable is similar to but distinct from another form, i,e., the parable. The latter is a short story, whose function is a moral lesson, but which uses humans as the main characters.

| Fable | Lesson |

| The Ant and the Dove | Return favors given to you. |

| An Ant and a Fly | Work honestly and you won’t be scorned. |

| An Ant formerly a Man | At the root, people stay the same if if they look like they are changing. |

| The Ant and the Grasshopper | Prepare for the future. |

| The Flea and the Wrestler | We petition the gods for minor matters, yet often take offense if such petitions are not granted. |

| The Flies and the Honey Pot | Too much of a good thing can be bad. |

| The Fly and the Draught Mule | Ignore complainers who have no influence. |

| The Gnat and the Bull | Some men are of more consequence in their own eyes than in the eyes of their neighbors. |

| The Gnat and the Lion | No matter how you brag, you can be undone. |

Not surprisingly, insects are very well represented in fables. A short list includes those found in Table 7.1 (above). In each case, an insect is used to teach a moral lesson. Once specific example of an insect-based fable is the grasshopper and the ant. On a summer’s day, the grasshopper is out having a good time, hopping hither and yon, drinking cheap beer (okay, that really isn’t part of the fable), and generally wasting time. In contrast, the ant is assiduously collecting food and putting it away for the winter. The grasshopper tries to get the ant to come join him in having fun but the ant is wise and refuses. When winter comes, the ant is well provisioned while the grasshopper dies from hunger. As in the case of myth, specific features of the insects’ biology are used to tell a story. What are these? What is the lesson being taught?

The Greeks were fond of using all sorts of stories to teach life lessons. In addition to fables, which use an animal of some sort to teach a lesson, Greeks also use parables, in which the principal characters are human. All of these diverse methods of interpreting the world and human behavior can be subsumed into the general category of folklore.

At this point, you should be able to go back to your original definition of myth and add some nuances to it. After reading this chapter, what is/ are the purpose(s) of myth? How are insects used for this purpose? What features of their biology commend them to this purpose?

Now that you’ve thought about, and ideally written, your own definition of myth, here are the definitions from some experts:

“Greek mythology is largely made up of stories about gods and goddesses, but it must not be read as a kind of Greek Bible . . . It is an explanation of something in nature: how, for instance, anything and everything came into existence; men, animals, this or that tree or flower . . . Myths are early science, the result of men’s first trying to explain what they saw around them.”

–Edith Hamilton, Mythology

“Mythology is the study of whatever religious or heroic legends are so foreign to a student’s experience that he cannot believe them to be true . . . Myth has two main functions. The first is to answer the sort of awkward questions that children ask, such as: ‘Who made the world? How will it end? Who was the first man? Where do souls go after death?’ . . . The second function of myth is to justify an existing social system and account for traditional rites and customs.”

–Robert Graves, “Introduction,”

New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology

“Myths are things that never happened but always are.”

–Sallustius, 4th cent. A.D.

(Quoted in Carl Sagan’s Dragons of Eden)

Did you come close to capturing the ideas about myth enunciated by the “experts”? For our purposes, you need to take away two ideas: myths (fables and parables) can serve the function of explaining natural phenomena. A myth may also serve a broader social function, such as providing a rationale for entrenched social mores and serving as a mechanism for communicating with gods. Insects have played important roles both in helping ancient people understand nature and in constructing and justifying the prevailing social norms under which they lived.

References

Chapter 7 Cover Photo: Engraving by Nicolaes de Bruyn, 1594. CC0 Public Domain. Accessed via karlshuker.blogspot.com

Figure 7.1: Species Scape, author unknown. Accessed via http://yourwildlife.org/2016/09/updating-the-species-scape/

Figure 7.2: Hopi Reservation map, author unknown. Accessed via http://www.viewzone.com/day6.html

Figure 7.3a: Image of Robber Fly Kachina Doll (carved by Ryon Polequaptewa). Accessed via http://www.whitewolfpack.com/2015/01/traditional-hopi-kachina-dolls-and.html

Figure 7.3b: Robber Fly. CC0 Public Domain, ardikhoirunnadlif. Accessed via https://pixabay.com/en/macro-robber-fly-animal-wildlife-1542522/

Figure 7.4a: Image of Butterfly Man Kachina Doll (artist unknown). Accessed via http://www.johnhillgallery.com/kachinas

Figure 7.4b: Image of Butterfly Maiden Kachina Doll (carved by Alvin Navasie Sr.). Accessed via http://www.museumfoundation.org/product-707/Butterfly-Kachina

Figure 7.4c: Image of Cricket Man Kachina Doll (carved by Eric Kayquoptewa). Accessed via https://shops.musnaz.org/shop/shop/kachina-dolls/traditional-kachina-dolls/cricket-father-kastina/

Figure 7.5: Tachinid fly. CC0 Public Domain, mikadago. Accessed via https://pixabay.com/en/macro-insect-fly-animal-bug-1150677/

Figure 7.6: Adult dragonfly. CC0 Public Domain, 258817. Accessed via https://pixabay.com/en/dragonfly-insect-animal-wing-348433/

Table 7.1: Information compiled by S. W. Fisher, from various sources

Additional Readings

Cherry, R. (2011). Insects and Death. American Entomologist 57: 82-85.

Kritsky, G. and R. Cherry (2000). Insect Mythology. Writers Club Press, Lincoln, NE, 137 pp.