Cultural Expectations on Teaching and Learning

Cultural differences can generate different expectations on teaching and learning. Watch the following video and answer the reflection questions:

Reflection Questions:

- Summarize the content of the video

- What’s your opinion on the content of the video?

- How have you prepared yourself to study in another culture?

- What might be your concerns?

- What do you think is the priority for learning in U.S. classrooms, that is, what goal are they trying to achieve by teaching in the way that they do?

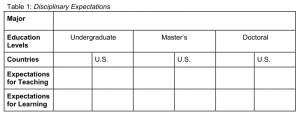

Of course, cultural expectations on teaching and learning could also vary across disciplines. For example, students from Humanities and Social Science are usually required to write and speak more in class than those from STEM which often asks their students to solve particular problems. Thus, there are different disciplinary expectations on teaching and learning.

Do you know the cultural expectations on teaching and learning in your disciplines at different education levels (i.e., undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral levels) ? Please fill out Table 1 below with what you know. In the left box in the row for “Countries”, please fill in a country you are familiar with to compare to the disciplinary expectations of the U.S.

Reflection Questions:

- Is it easy or difficult to fill out the table? Which part is easiest and hardest to fill out? Why?

- Where did you get the information? Are you familiar with the faculty and staff of your department?

- Is there anything surprising to you?

Compare your table with someone from a different discipline and answer the following questions:

- What is similar or different between the two disciplines?

- What is surprising to you?

Teaching and learning at the tertiary level can take place in different styles across the same or different countries. You may come from an educational culture that values teacher-talk and students’ engagement in rigorous note-taking rather than interaction in the classroom. Final exams may be the only evaluation of your academic performance of the semester. However, in most U.S. universities, a student-centered teaching style is more common, which means teachers usually take roles of a guide, bridge, or facilitator in class and students participate in individual or collaborative projects, active discussions, and presentations, in addition to more traditional assessment components, such as quizzes, mid-term and final exams. In this way, the need for a large assessment, such as a final exam, is less important, as the teacher is more able to assess students, particularly their language use and communicative ability, through their frequent classroom interaction–some instructors will grade for participation, so be sure to speak up!

At the graduate level, you will be given more opportunities in taking seminars in which you and your cohorts will discuss and share ideas with each other. Your professors may barely be involved in discussions. Many international students have felt frustrated because their discussions with classmates did not lead to solutions but probably more questions. In their understanding, the professors should provide the correct answer at the end of the class. This, however, is seen as detrimental to students’ intellectual growth because knowledge at the graduate level is not a thing to be given by professors but discovered by graduate students through their discussions and research, a process that can happen individually, or collaboratively with their cohorts and professors. Bloom’s taxonomy can best demonstrate different levels of learning.

Like Bloom’s Taxonomy shows, for graduate studies, one of the main purposes of learning is to create knowledge, which is at the top of the pyramid, meaning it is only done by few people and full of difficulty and challenge. However, you are selected and trusted by your program to embark on this strenuous task, a task which you will increasingly find is more and more your own journey as a developing expert rather than something simply taught to you by an instructor. In some sense, you must learn to teach yourself, but as a result, the value of any person’s education at any level can be greatly improved by their own effort and engagement with the learning process.

Because much of graduate education is about developing the ability to participate in professional and scholarly negotiation and critique, this interaction between students may be both more common and more important than your previous studies. The qualification represented by graduating is something you will fight for and develop gradually each day of the next few years. Graduation is to acknowledge that you have become a scholar; it does not make you a scholar by itself. Right now, the idea of graduating may seem like a big deal, but perhaps by the time you get to that phase, it will feel more and more like a formality as the real work will have already taken place.