Main Body

The Power of Resilience: How Stewards in Palliative Healthcare Settings Can Leverage Resilience to Combat Staff Burnout

Nicholas Fowler

Introduction

Burnout is no stranger to the palliative healthcare industry. Day in and day out palliative healthcare staff are faced with stressors that are both common to the healthcare industry as a whole and unique to palliative healthcare alone. These stressors can often lead to chronic burnout among the palliative healthcare staff members. The good news is that there are steps that can be taken to help mitigate and potentially alleviate the symptoms of burnout. One could argue that stewards within palliative healthcare teams are not only in a position to use this knowledge to help their teams but are actually obligated to do so. Throughout the rest of the chapter we will explore the palliative healthcare field through a Positive Organizational Scholarship (POS) lens to investigate how stewards can use resilience training as a tool to combat the negative effects of burnout within their teams.

Burnout, in simple terms, is a loss of energy. This sense of energy loss can manifest itself in both physical and psychological forms. We have all probably experienced burnout in some way, shape, or form. One may feel a sense of physical burnout after a long day of helping a friend move into their new home, continually working muscles that you may have not used in that way in years for an entire day. A sense of psychological burnout could occur after hours and hours of cramming for a big test that you have been procrastinating for weeks. We are fortunate in that our burnout is usually temporary and only occurs a few times throughout the course of our life. However, for some, burnout is an everyday occurrence, and can have potentially negative outcomes for those experiencing this phenomenon.

For those working in palliative healthcare, burnout, in some shape or form, is nearly a certainty. Individuals working in palliative healthcare settings have been found to experience similar levels of stress as their non-palliative healthcare working peers, and there is some evidence that those working in healthcare settings in general experience much more stress relative to the general working population (Ablett & Jones, 2007). The emergence of Positive Organizational Scholarship offers an opportunity to explore how palliative healthcare staff can combat burnout and have more reasons to smile.

One key concept in Positive Organizational Scholarship (POS) is “resilience.” According to Shawn Murphy, in his book The Optimistic Workplace, resilience is the ability to recover from, adapt to, and grow from setbacks. As noted above, working in palliative healthcare can lead to a multitude of setbacks that might test one’s resilience. These setbacks may be viewed as stressors. In fact, these are the same stressors that lead one to burnout. Shawn Murphy, says the good news is that resilience can indeed be developed and that positive emotions such as joy, interest, and pride help individuals to build resilience (Murphy, 2016).

Due to their unique positioning, middle managers have the capacity to make for very large, and substantial change in palliative healthcare. Middle managers are oftentimes in the loop with the goals and initiatives that senior leadership hope to push but also have rapport and influence with those on the ground level, giving them great opportunity to influence change within an organization (Hagland, 2005).

Although most are familiar with the term “manager,” for the sake of this chapter the word steward will be used in its place. The words “manager” and “management” may have negative connotation for some. Inherently, these words may raise issues of “management” being in control over or dominating subordinates. This chapter changes the language of manager to steward in order to explore the positive aspects of leadership (Murphy, 2016). This chapter is about capitalizing on the foundations that POS has created to help people and organizations within the palliative healthcare field flourish and thrive. This cannot be accomplished unless there is a shift in the way in which people view the role of mangers, and instead think of them as “stewards.”

Stewards operate from a place of caring for individuals. Rather than using their position to dominant or impose their will upon others, they use their position to inspire, motivate, and support the members of their team. Stewards view it as their responsibility to coach, guide, mentor, and motivate people to be the best version of themselves, facilitating team members to achieve greatness through their actions and their words (Murphy, 2016).

This subtle change of jargon may seem trivial, so why even bother? The answer, language matters. We do not have to search very hard to find an example of this play out in real life. Let us look at the opioid epidemic that has taken so many lives and has impacted nearly every corner of the United States. Stigma is one problem that has been perpetuating this epidemic, and much of this stigma has to do with the language that is used to describe the people that have an addiction, a disease, that may lead them to use either prescriptions, illicit opiates, or both. For example, are people going to put in the time and effort to help change the culture for a junkie or an addict? Probably not. But they may be willing to work toward a culture where a person with a substance use disorder is able to access the resources that they need to live a happier healthier life.

As shown above, when trying to change a culture, language really does matter. So, in order to perpetuate the culture that this chapter is advocating for, it is important that language is used that reflects the culture to be instilled. Therefore, to stay true to the more modern discipline of POS, it is important that one uses language that illustrates a more modern view on management. Hence, the importance of using the term steward/stewardship as opposed to the term manager/management.

With this new vocabulary and vision of stewardship put in place, the foundation is set for the pages that will follow. The remaining pages of this chapter will outline the importance of resilience in the battle against burnout that palliative healthcare staff are all too familiar with. As we have already established, resilience may be developed, and it is the responsibility of stewards within the palliative healthcare field to empower individuals to develop resilience to help defend themselves from the stressors that come along with working in such a line of work.

Palliative Healthcare

First, it is important to understand what palliative care is and why it is such an important part of the healthcare system. The World Health Organization, whose goal is to “build a better, healthier future for people all over the world,” defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.” The WHO breaks down the role purpose of palliative healthcare providers into the following practices:

• Provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms

• Affirms life and regards dying as a normal process

• Intends neither to hasten nor postpone death

• Integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care

• Offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death

• Offers a support system to help the family cope during the patient’s illness and in their own bereavement

• Uses a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families, including bereavement counselling, if indicated

• Will enhance quality of life, and may also positively influence the course of illness

• Is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and includes those investigations needed to better understand and manage distressing clinical complications (Sepúlveda, Marlin, Yoshida & Ullrich, 2002)

Thus, palliative healthcare is unique from other forms of healthcare work. Many people seek out typical healthcare services in hopes of healing and getting better. However, in a palliative healthcare setting, as noted above, there is typically no hope of getting better. Quite the contrary is actually true. Those seeking out palliative healthcare do so because there is no “getting better,” as death is imminent. This unique situation presented by palliative healthcare, a focus on quality of life until their dying day rather than a focus on the quantity of days left, makes for an incredibly high risk of stress, depression, and burnout for palliative healthcare workers (Hulbert & Morrison, 2006).

Due to this disconnect, those working in a palliative healthcare setting could potentially experience a unique type of stress. Oftentimes, professional training for healthcare workers involves a curative focus, however, this is not the reality for those working in a palliative healthcare setting. This disconnect could lead to a sense of helplessness and dissatisfaction that staff in other healthcare staff do not have to cope with as regularly in their work (Ablett & Jones, 2007).

After understanding all that palliative healthcare staff must do, this reality should come to no surprise to anyone. Because of this, it is critical that palliative healthcare organizations do all that they can to not only minimize these negative outcomes, but to work day in and day out to help their employees build resilience to overcome such stressors which may come with the role of working in palliative healthcare. Not only will this have a positive impact on the palliative healthcare staff but improve the outcomes of the patients and their families as well.

Positive Organizational Scholarship

Throughout the entirety of this chapter, we will be exploring resilience through a lens of Positive Organizational Scholarship (POS). Therefore, it is important that time is taken to understand what POS is, and how it came to be. According to Kim Cameron and Arran Caza, POS is “is a new movement in organizational science that focuses on the dynamics leading to exceptional individual and organizational performance such as developing human strength, producing resilience and restoration, and fostering vitality” (Cameron & Caza, 2004). To fully understand POS we will first take a delve into its foundation: positive psychology.

Dr. Martin E. P. Seligman is often accredited as the pioneer of the positive psychology movement. As the story goes, Seligman and his daughter were pulling weeds in the garden, but his daughter could not stop playing and singing as they tried to complete the chore. Seligman snapped, yelling at his daughter. She snapped back, stating that she had given up whining because he had asked her to, and if she could stop that, he could stop being such a grouch. It was in that moment that Seligman realized that raising his daughter was not about stopping her from whining, but rather nurturing her strengths, enabling her to flourish and thrive (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000).

Seligman, the president of the American Psychological Association at the time, noticed, like the way he had been raising his daughter, the field of psychology had been focusing far too much on fixing what was wrong with people rather than focusing on the aspects of people’s lives that made life worth living. This deficit approach had taken hold shortly after World War II, focusing on disease model and healing the mental deficits that people were experiencing.

Although focusing on the pathology of mental health is very important, this mindset neglected to consider those individuals and communities that were thriving, and failed to help them build upon those skills to enable them to live the life that they wanted to live.7 Due to the work of Seligman and other colleagues in the field, positive psychology has become more and more present in many fields of work. However, many doctors still operate under the deficit model that Seligman had been trying to abandon.

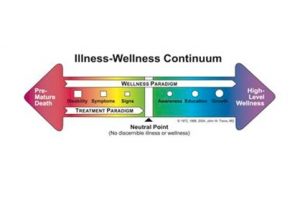

For example, in an article written by The Atlantic on March 21, 2018, Helen Mayberg, an American neurologist known for her studies of using deep-brain stimulation for the treatment of severe chronic depression, said “It’s not my job as a neurologist to make people happy. I liberate my patients from pain and counteract the progress of disease. I pull them up out of a hole and bring them from minus ten to zero, but from there the responsibility is their own” (Lone, 2018). The field of positive psychology has come a long way from the time that Seligman had his revelation near the turn of the 21st century, however, it is easy to see from this quote the remnants of a deficit based model are still seen today. This notion of only being concerned with getting patients from a state illness to state of okay can be illustrated on a continuum.

Another way to frame this is by looking at the Illness-Wellness Continuum, created by Dr. John Travis (Figure 1-1). Psychologists seemed to spend a great deal of time on the left-hand side of the continuum, working within the treatment paradigm. Although this was helpful, it only got patients to a neutral point. What Seligman was calling for was a shift in perspective, helping patients that were already beyond the neutral point. In other words, he wanted to focus on how psychologists can help patients thrive rather than simply survive. This model of thinking, however, is not unique to healthcare. Businesses and organizations, too, can be bogged down by thinking only of curing the illnesses of bad business practices, fixing troubled employees, or putting a bandage on the wounds that bleed profits and productivity out of organization. Shifting the focus from trying to fix all that can go wrong in a business to a focus on the conditions that allow for great businesses to thrive is the essence of POS.

Figure 1-1

Now that there is a clearer understanding of the foundations of POS, it is time to dive deeper into POS. In the book titled Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline by Kim Cameron and Jane Dutton, POS is further explained by breaking down the three words that make up POS: positive, organizational, scholarship (Cameron, Dutton & Quinn, 2003). POS focuses on positive states, rather than focusing disproportionately on fixing what has been going poorly in the past. Within POS, there is an aim to focus on patterns of excellence, and in particular, phenomena that tend to deviate from the norm in a positive manner. These positive phenomena of focus are phenomena that tend to give organizations the ability to flourish and thrive, not simply survive as observed in the organizational scholarship of the past (Cameron, Dutton & Quinn, 2003).

The organizational aspect of POS is highlighted by the focus on phenomena that occur within organizations, as well as the context of the organization itself, bringing the oftentimes overlooked positivity to the forefront of focus. Subscribers of POS look to focus on how performance can be driven by promoting meaningful work for employees, aligning work toward employee strengths, and empowering those employees in a manner that promotes inclusion within, and with stakeholders outside of, the organization. This is a far cry from the typical focus on mitigating negative consequences that lead to poor performance (Cameron, Dutton & Quinn, 2003).

Unlike many of the self-help books that have been published that tout the power of positive thinking or the parables of perseverance, POS is deeply rooted in the scientific method. In a way, it takes the self-help literature to another level, focusing on a desire to “develop rigorous, systematic, and theory-based foundations for positive phenomena” (Cameron, Dutton & Quinn, 2003).

What causes burnout?

In the introduction, burnout was defined simply as a loss of energy that can manifest itself either psychologically or physically. However, what needs to be explored further is what causes burnout, and in particular, what causes burnout in individuals working within the palliative healthcare setting. Research has shown that palliative healthcare staff face a unique set of stressors. These stressors include, but are not limited to: constant exposure to death, inadequate time with dying patients, growing workload, inadequate coping with their own emotional response to the dying, increasing number of deaths, communication difficulties with dying patients and families, and feelings of grief, depression and guilt (Slocum-Gori, et al., 2011).

One major cause of burnout that is commonly noted in palliative healthcare is “compassion fatigue,” otherwise known as, ‘the cost of caring’. Although not unique to palliative healthcare settings, this phenomenon is unique to helping professions, making it a great concern for palliative healthcare workers. Such stress has been known to show signs with little warning and can lead to helplessness, depression, and stress-related illness (Slocum-Gori, et al., 2011).

Resilience

“Resilience” was first explored when trying to better understand children that were maltreated and is a core aspect of the POS paradigm. “Resilience” applications have been used far beyond the realm of understanding its role in the lives of children that have been treated poorly. A myriad of diverse fields, including psychology, psychiatry, sociology, business, and biological sciences, have started to further explore resilience. Because of this there is no single definition of what resilience is, but, for the context of this chapter, we will define resilience as the “positive adaptation, or the ability to maintain or regain mental health, despite experiencing adversity” (Murphy, 2016).

The term “Grit” has also gained a lot of traction and has been used interchangeably with the term “Resilience.” This has been fueled even more by the release of Angela Duckworth’s book Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. Although similar, there are some differences between the two that make them not so interchangeable. As described earlier, resilience is an optimistic mindset that motivates one to continue going on in the face of adversity. Grit, however, is a term that describes one’s passion and perseverance toward a long-term goal (Duckworth, 2016).

Although these two concepts tend to intertwine a lot they are not interchangeable. One may have to exhibit a lot of resilience along the path to long-term goals. For example, a future hospice nurse may have to show a lot of resilience to bounce back after receiving a C score on his or her first epidemiology exam, but the deliberate practice to learn the skills necessary to obtain the nursing degree may require a lot of grit. Although not synonymous, these two words are both valuable in deterring burnout, and seem to dance together a lot within the same ballroom.

So, why exactly is grit important in developing resiliency amongst palliative healthcare staff? As stated earlier, grit is a combination of passion and perseverance. It is in this perseverance that one may see resilience shine the most, particularly perseverance over adversity. In Duckworth’s book, mentioned above, she cites the work of Carol Dweck. Dweck, earned her PhD in psychology and has focused her attention on mindset and the impacts that it has on perseverance. In particular, the benefits of a growth mindset over a fixed mindset. Over her years of studies, she has determined that having a growth mindset leads to a more optimistic view of adversity. In other words, individuals with a growth mindset tend to be more optimistic, viewing adversity as a challenge that is temporary and within their control (Duckworth, 2016). It is this connection between the perseverance of grit and the ability to overcome adversity that we find the connection between resilience and grit. This is further demonstrated below in Figure 1-2.

Figure 1-2

Putting the Pieces Together

Now that we have all of this knowledge about burnout, palliative healthcare, and resilience, it is time to explore how all of these pieces of the puzzle fit together. How might middle management in palliative healthcare settings measure resilience be good stewards of resilience amongst members of their team and ultimately use resilience as an asset to combat all of the negative side effects that come with burnout? At this point in the reading, readers may have come to some of these answers on their own. However, in this section we will continue to explore the practical application of resilience in palliative healthcare settings and how it can lead to a happier and healthier workforce.

First, stewards must understand how to measure resilience among team members. In 2011, a group of researchers published a systematic review of resilience measurement scales. Through this review, they were able identify 15 measures that were intended to measure resilience in various populations. However, not all of these assessments are geared towards adults; in fact, more than half were not. When looking at the scales geared toward adults, the population most likely to be working in palliative healthcare setting, there were a few that were found to be of higher quality than the rest. Even the highest rated resilience assessments seemed to be of moderate quality at best (Windle, Bennett & Noyes, 2011).

There is a growing body of research that suggests there are ways in which resilience can be developed. One such way that evidence seems to support is the practice of mindfulness. Mindfulness is defined by some as “a state in which one is able to give uninterrupted attention over a period of time in a nonjudgmental way to ongoing physical, cognitive and psychological experience, without critically analyzing or passing a judgment on that experience” (Bajaj & Pande, 2015). Put simply, mindfulness is the ability to be present in the moment, and experience events and sensations for what they are. This may seem to some as a form of pseudoscience, but there is more and more research that is being published every day that points to mindfulness as an effective tool for people of nearly all walks of life. If looking for ways to incorporate mindfulness into professional development, staff meetings, or training, the Positive Psychology Toolkit can be a great place to start.

For those who still do not believe in the benefits of mindfulness, look no further than the United States Military. There are not many higher stress events that one may experience than live combat. According to an article posted on the United States Army website, mindfulness was shown effective to build not only cognitive resilience, but the brain’s ability to pay attention during training as well.

Mindfulness has shown so much promise that the military’s STRONG Project, standing for Schofield Barracks Training and Research on Neurobehavioral Growth, which has been granted over $1.7 million to continue researching the impacts of pre-deployment mindfulness and resiliency training (Myers, 2015). It is not only pre-deployment military personnel that is benefitting from the benefits of mindfulness; military veterans that have been diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have also seen benefits of mindfulness in their treatment.

Similar to palliative healthcare staff members, military personnel are oftentimes exposed to high stress environments and the reality of death. This can lead to high rates of PTSD and depression. Mindfulness exercises have been shown to significantly decrease both PTSD and depression severity in military veterans (Boden, et al., 2012). This is just one more example of the benefits of mindfulness exercises and the need for further mindfulness research. It seems as if mindfulness is powerful, but it is not the only way in which one can develop resiliency.

Angela Duckworth cites a study done by Steve Maier in her book. This study showed that it is not adversity alone that builds resilience in individuals. The old adage “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” is true to a point. It is the sense of having some sort of control over one’s circumstances that has been shown to “make you stronger.” Those who have a sense of no control over the adversity that plagues them will often fall into this state of learned hopelessness, destroying resilience. It is not the adversity that tends to build resilience, rather the way in which people are able to and equipped to respond the adversity that comes their way (Duckworth, 2016). This means that stewards can build resilience in employees by fostering hope and providing ways for individuals to overcome adversity in a positive way.

Individuals that have been shown to have high hope often view adversity differently than those with low hope. Adversity, otherwise known as goal blockages, can lead to negative emotions in individuals with low hope, but those with high hope often view this adversity as a challenge to overcome. Studies have shown a correlation between high hope and higher achievement and lower levels of depression, while their low hope peers demonstrated a decreased sense of well-being among other negative outcomes (Hanson, 2009).

Adult Dispositional Hope Scale

The Adult Dispositional Hope Scale, a twelve question self-assessment graded on an eight-point Likert scale, has shown to be reliable and valid, and is used in people 15 years of age and older.16 This is yet another test that stewards can use in palliative healthcare onboarding or professional development conversations in order to assess and discuss an employee’s sense of hope in the workplace and in their lives.

Snyder divides hope theory into four distinct categories: goals, pathway thoughts, agency thoughts, and barriers (Hanson, 2009). One way to develop hope in individuals may be to engage in dialogue that involves these four areas. Establishing “goals” for an employee can give them an endpoint to view in their hopeful thinking (Hanson, 2009). Therefore, it is important that stewards take time to work with their employees to establish meaningful goals, and check in regularly on how the goal attainment is coming along.

“Pathway thoughts” are the ways in which people hope to explore in order to achieve their goals. This means it is not only important for stewards to help employees set meaningful goals, but explore with them how they might go about achieving those goals. Agency thoughts refer to the motivation one might have to undertake the route needed to be explored in order to achieve those goals.16 In this context, it is essential for stewards to know the purpose of the organization and the team member. It is worth exploring the strengths and passion of the team member to help them realize how their goals can be fulfilling to them.

Palliative nurses may feel a great sense of connection to their work because they feel their purpose is to offer relief to people in some of their most trying times. Setting goals that orient toward a nurse’s purpose will most likely lead to the greatest sense of motivation to pursue the paths needed to achieve his or her goals. Finally, barriers are the things that hinder individuals from attaining their goals. These can either cause someone, typically with a low sense of hope, to give up on their goals or motivate individuals, usually those with a high sense of hope, to find new routes to take on their way to their goals (Hanson, 2009). Stewards that are experienced and forward-thinking may be able to use some foresight to identify future barriers, or even challenge team members to look ahead and see what barriers there may be, preparing them to face such adversity shall it arise.

Although hope and mindfulness are only a couple of things that stewards can do to build resilience within their teams, it is a start in the right direction. What is important to takeaway is that resilience is not fixed; it can be developed and fostered through meaningful intervention. This not only provides palliative healthcare workers on the front line the ability to grow as individuals, but give stewards and organizations the opportunity to provide protective factors to their teams against burnout.

Challenges and Future Exploration

Although researchers have been studying the impacts of Organizational Scholarship (OS) for decades, the field of Positive Organizational Scholarship (POS) is a fairly new frontier of exploration. As more POS research floods the field of OS, we are learning how impactful POB can be in the workplace. From the limited studies, it seems as if the palliative healthcare field is no different, but more research needs to be done. POS consists of many factors other than resilience, and focusing research on resilience alone is far too narrow. I would encourage more research on the implementation of a fully immersive culture of POS in healthcare settings. With the great deal of overlap, it is also natural to expect that there would be a synergistic relationship between all of the POB pillars. These synergies deserve much more research in the future in order to fully unlock the potential of resilience and POS as a whole.

Nearly all of the research thus far seems to focus on the palliative healthcare staff or patients that are terminally ill. However, with the expansion of the WHO’s definition of palliative, it is important that researchers take into account the impacts on the families whose loved ones are ill. Resilience is oftentimes viewed as a characteristic or trait of an individual in much of the research that has been conducted. This focus may erroneously lead people to believe that resilience is the sole responsibility of the individual developing it. When we hear stories of resilience we oftentimes hear parables of overcoming incredible amounts of adversity in order to accomplish great feats. For example, the football player that overcomes cancer and is still able to play in the National Football League, or the child that grows up in a zip code that is well below the poverty line and raised by two parents that were constantly in and out of jail but is able to overcome these obstacles to earn a PhD. In both of those examples we see individuals accomplishing amazing things, but what we do not see is the role that others played in this journey to success.

Regardless of the journey and the amount of resilience demonstrated, there is more to the picture that we often see. This is important to keep in mind. When it comes to developing resilience in palliative healthcare staff, or anyone for that matter, it is important to realize that organizations and other people played a role in the success of that individual. It is irresponsible for organizations to solely rely on individuals to develop their own resilience in order to overcome adversity and battle burnout. Organizations and middle management–stewards operating in the middle–need to view burnout as a threat to the workforce and give teams the tools that they need in order to overcome this affliction. It is critical that a proactive approach is taken.

Another important factor to keep in mind is that one does not have to overcome incredible odds or accomplish a great feat to be a paragon of resilience. In palliative healthcare, adversity is part of the job description. Just because it is the job of a palliative healthcare worker to provide services to an individual and their families during the dying process, it does not mean that bouncing back from the death of patient or helping a family through the grieving process is not a demonstration of great resilience.

Conclusion

No matter what field of work one might choose to pursue, there will be stressors. If left unattended these stressors can lead to a myriad of negative consequences, and if they persist long enough without any defense or interventions, they can lead to chronic burnout. Although this is a threat to anyone in the workforce, we have seen that healthcare workers tend to experience burnout at much higher rates than that of the average working American. In a palliative healthcare setting, staff members tend to experience roughly the same amount of stress and burnout at other healthcare staff, but the stressors they tend to experience are very unique to the field of palliative care. The good news is that resilience can act as a tool to combat the ill effects of burnout.

It is important that stewards in palliative healthcare settings use all the information at their disposal to create an organization that truly embraces the POS model. This means creating an environment that promotes the building of resilience in order to defend against burnout. First and foremost, it is important that stewards in palliative healthcare settings take time to get to know their team members. This may include performing nontraditional assessments such as measuring resilience, strengths, and burnout. Using one-on-one staff meetings and trainings as an opportunity to be intentional about building resilience can greatly benefit the staff and quality of care. Such activities may be exploring purpose, nurturing hope, and mindfulness-based activities.

Burnout is a serious issue that impacts far too many in palliative healthcare settings, however, it is an ailment that can be combatted. Through careful coaching and the implementation of POS pillars into the palliative healthcare setting, it is possible that stewards can help to eliminate, or at least lessen, the impact that burnout makes. As the future stewards of the healthcare industry, it is up to you how you will protect your team from the ill effects of burnout and help them become the best that they can be. Hopefully, after reading this chapter your course of action will be a little easier.