Main Body

Leadership Inclusiveness and Psychological Safety in an Inpatient Medical Team

John Guido

“I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” -Maya Angelou

Introduction

I am a current hospitalist physician in a large not-for-profit hospital in Columbus, Ohio. I have been practicing medicine for approximately three years. Physicians are the de facto leaders of an inpatient medical team, and rightfully so, as the overall care of the patient is their ultimate responsibility. My day to day duties require seemingly thousands of individual decisions. To do this effectively, and in the best interest of each unique patient, I need the honest input of each member of my entire medical team (consultants, nurses, therapists, social workers, etc.). We all differ in our own individual training and work/life experiences, and when combined can formulate the best treatment plan possible for the patient. This collaboration is actually more of a requirement than a luxury, as increasing amounts of medical knowledge and specialization has led to more interdependence of multidisciplinary medical team members. Partnership requires effective communication and a strong working environment.

Physicians who see patients on multiple different units across a healthcare system will be part of numerous multidisciplinary teams in contrast to the various “unit-based” nurses, therapists, care coordinators, and ancillary staff. This inherently creates a non-standardized workflow and a sense of unfamiliarity between the physician and other team members. In fact, the medical industry is unique in that the teams can be very dynamic (and this is really the norm), which is far different from most other service industries. Teams are based on each unique patient’s needs, may come together for short periods of time, consist of multiple specialists or other service providers, and must integrate numerous professional cultures (Manser, 2008).

In medicine, a perceived hierarchy exists where non-physician team members may defer their opinion/input to the physician for fear of reprimand or embarrassment. I have seen this first hand. This weakens the team morale and care for the patient. It is the responsibility of physician leaders to create an environment where every team member feels safe in offering their opinion without hesitation. This is generally not something a young pre-medical student takes into account, no matter what their intentions for entering the field may be. Given this, I have had to inwardly seek and adapt my own leadership style in a relatively brief amount of time.

Synopsis

The dynamic of inpatient medicine has been rapidly evolving such that physicians and other members of a comprehensive care team are more specialized than ever before. This creates an increased reliance of all members of the care team towards one another, with physicians acting as the leader. All members of the care team offer invaluable information, ideas, and expertise in caring for the patient, yet may feel apprehensive in speaking out due to fear of embarrassment or ridicule.

It is the ultimate job of the leader to create a culture of inclusion and mutual respect for all disciplines on the multidisciplinary medical team. This can be accomplished through the practice of leadership inclusiveness. This practice draws from several well-established leadership theories that serve to strengthen the relationship between the leader and followers as well as help followers become more comfortable with themselves, the team, and their situation. In turn, this creates a psychologically safe environment where all team members are able to work without fear of negative consequences. This ultimately enhances team member production, creativity, and satisfaction as well as improving communication between all members of the care team.

Changing Healthcare Dynamic and Creation of Multidisciplinary Interdependence

The dynamic of inpatient medicine, caring for patients in an acute care hospital, has changed dramatically over the previous decades. Gone are the days when general practitioners and family physicians would put in a full day’s work in a private practice outpatient clinic and then go to the local hospital to manage the full inpatient needs of their acutely ill patrons.

Science, innovation, medical advancements, and knowledge gains have rapidly progressed since that time, leading to an inpatient healthcare dynamic that would seem foreign to those earlier general practitioners. These advancements have led to countless new treatments that are allowing people today to live longer and healthier than at any other point in history. However, no single individual can any longer absorb all of the new knowledge and become proficient at all of the advanced techniques that are now standard in today’s hospitals.

This has led to the increased specialization of healthcare, necessitating an increased depth but with decreased breadth for healthcare professionals. This fragmentation of healthcare, while allowing the delivery of the best evidence-based medicine possible, has led to the division of critical knowledge amongst many different practitioners. This knowledge division has in turn lead to the creation of multidisciplinary teams with increased interdependence of working group members. The team as a whole depends on the expertise and input of each individual member which is then integrated to formulate an all-encompassing care plan for the patient. However, multidisciplinary collaboration is something that must be actively learned and improved upon. It is generally not inherent. The Institute of Medicine’s landmark report Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21 Century notes that “members of teams are typically trained in separate disciplines and educational settings, leaving them unprepared to practice in complex collaborative settings” (Institute of Medicine, 2001).

The Inpatient Healthcare Team of Today

The typical inpatient care team would likely be unrecognizable to practitioners of prior generations. There are currently many different healthcare professionals and specialties that may be involved in the care of any particular patient. Each group member has a unique knowledge and skill set that will be used in creating an overarching care plan for the patient. Plans of care can realistically change from moment to moment depending on the evolving clinical status of the patient. For this reason, teams are being increasingly valued for their potential to innovate, solve problems, and implement change (Nembhard and Edmondson, 2009). Just like plans of care, team members are also dynamic, ever changing based on the patient’s needs. A typical medical inpatient care team and their general responsibilities would be comprised as follows: (Freshman et al., 2010)

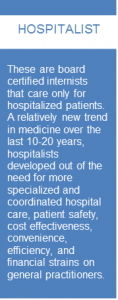

- Hospitalist – serves as the primary medical decision maker.

- Consultants – physicians with a specialized area of expertise, often within a single organ system (cardiologist, oncologist, neurosurgeon, etc.). With advancements in knowledge, medicine, and technology, the number of consulting specialties has grown rapidly. Today, there are 26 specialties and 93 subspecialties within the major specialties (Nembhard and Edmondson, 2009). Hospitalists may seek advice or services from a consultant depending on the needs of the patient.

- Nurses – provide the primary bedside hands-on care to patients by administering medications, managing intravenous lines, observing and monitoring patients’ conditions, maintaining records, and communicating with doctors.

- Pharmacists – prepare medications, offers pharmacological information to the multidisciplinary health care team, monitors patient’s drug therapies.

- Therapists – physical, occupational, and speech therapists give evaluation of, and prognostic information regarding, the functional limitations of a patient as well as individualized exercise therapy treatment programs.

- Ancillary service providers – any of the many numerous remaining diagnostic, therapeutic, and custodial service providers.

- Care coordinators – case management and social workers provide patient education, monitor treatment and insurance coverage plans to ensure that a patient’s needs are entirely met, and coordinate services needed after discharge.

Physicians possess specialized medical expertise while nurses, therapists, and ancillary service providers have a greater deal of bedside patient-provider interaction. Ideally, the comprehensive medical team would integrate the various skills and professional expertise of each member to realize the maximum patient benefit. However, this is often “easier said than done.” Care is becoming increasingly complex, broader in scope, and more challenging – thus, compiling an effective and efficient medical team has also become more challenging.

Generally, the production of high-quality care is not hampered by lack of clinical expertise in the individual professions but rather by lack of appropriate knowledge and experience among these groups as to how to make these multidisciplinary teams work well (Freshman et al., 2010). Improving the quality of care delivery processes necessarily requires different viewpoints, each grounded in deep knowledge of a different aspect of the process (Nembhard and Edmondson, 2009). Yet, many health professionals tend to operate in uni-professional silos that can make knowledge sharing more difficult. Diversity and the resultant unfamiliarity, if not managed well, can lead to friction, hostility, and poor performance (Mitchell et al., 2015).

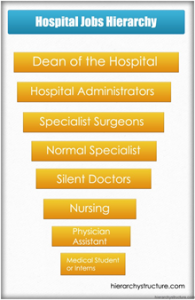

Medical Professional Hierarchies

The existence of physician/physician and physician/non-physician hierarchies in and amongst medical professionals has been well established. Non-formal hierarchies in medicine are generally based on a multifaceted set of characteristics: power, wealth, time invested in training/clinical practice, effort regarding rigor and roughness of practice, measurable skills, and increasing level of specialty (Aguirre et al., 1992) whereby those that possess more of these characteristics are seen as superior to those who do not. Physician status is generally viewed as more prestigious than non-physician status (Schwartzbaum et al., 1973).

The existence of hierarchies in medicine is problematic in that it discourages members of the healthcare team from speaking across professional boundaries, leading to decreased communication, problem-solving, and opportunities for quality improvement. Persons of perceived lower status are more likely to underestimate their value and contributions to the medical team. Medical hierarchies have been significantly associated with undesirable patient outcomes (Feiger and Schmitt, 1979) and increased medical errors (Institute of Medicine, 2003).

The Communication Divide

Despite the need for increasing collaboration across multidisciplinary teams, effective communication can break down for a variety of reasons (Nembhard and Edmondson, 2009). More risk-averse persons may be unwilling or afraid to participate in team medical decision making. The reason for this is as more care has been directed to the outpatient setting, persons who are admitted to the hospital today are generally more acutely ill then previously. This raises the stakes of participating on a multidisciplinary medical team, which unlike other service industries, is engaged in more fast-paced and uncertain situations (Edmondson, 2003). Patient care is highly actionable and a single mistake can have serious consequences. While leadership inclusiveness and psychological safety can be beneficial in the above situations, these leadership tools are most commonly thought of in relation to communication deficiencies related to medical hierarchies. Perceived status differences and inability/unwillingness to cross role boundaries has been shown to lead to poor communication (Atwal and Caldwell, 2005). In the same vein, people tend to act as “impression managers,” meaning that they are reluctant to engage in behaviors that could threaten the image others hold of them, such that in the presence of others with more perceived power, subordinates may fear being seen as ignorant, incompetent, negative, or disruptive if they speak out (Edmondson, 2008). Overtime, if left unchecked, this creates a learned pattern of behavior that is detrimental to the overall function of the team. These theories are supported by the findings of Atwal and Caldwell, who in observing the real day to day functions of numerous multidisciplinary medical teams, found that physician leaders were highly active in participation, physical and occupational therapists as well as social workers were rarely involved, and nurses were involved to a varying degree (Atwal and Caldwell, 2005).

Leadership Inclusiveness and Leadership Theory

“The art of communication is the language of leadership.” -James HumesIt is possible to negate or balance these fears as well as status and other differences by creating a culture of inclusion and mutual respect for all disciplines on the multidisciplinary medical team. This should be modeled by the designated leader (most typically the attending physician of record) as followers look to leader behaviors, actions, and advice for clues regarding how to act and what is expected of them. This can be accomplished through the practice of leadership inclusiveness, which is defined as the “words and deeds exhibited by leaders that invite and appreciate others’ contributions” (Nembhard and Edmondson,2009). The foundation of leadership inclusiveness draws from several well-established leadership theories, most notably the Behavioral Approach, Leader-Member Exchange Theory, and Authentic Leadership.

The explicitly stated focus of the Behavioral Approach is in regard to “what leaders do and how they act,” including the “actions of leaders toward followers in various contexts” through the combination of task and relationship behaviors. Leader task behaviors help followers to achieve their goals while relationship behaviors help followers to feel comfortable with themselves, the team, and their situation (Northouse, 2018). An equal and strong concern for results and interpersonal relationships, as is the case on an inpatient medical team, leads to a “team management” style with high levels of member participation, teamwork, and commitment. Qualities of a Behavioral Approach leader that practices a team management style are: stimulates participation, acts determined, gets issues into the open, makes priorities clear, follows through, behaves open-mindedly, and enjoys working. These are all characteristics that physicians should strive to achieve when leading a medical team.

Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Theory conceptualizes leadership as a “process that focuses on the interactions between leaders and followers.” The dyadic leader-follower relationship is central to this theory (Northouse, 2018). Within every organizational work group, inpatient medical teams not excluded, each member will become part of the in-group or out-group based on their interactions with the leader and willingness to take on non-contractual responsibilities. “Personality and other personal factors largely make this determination. In-group members are afforded more information, confidence, and concern from the leader which leads to a state of mutual trust, respect, and influence” (Northouse, 2018). Each member of the medical team has a unique personality, and without leader awareness and support, some may more easily find themselves in an out-group. This is detrimental to the overall function of the team and patient care, as each member is the “team expert” in their designated field, and input from each member is needed to create the best possible comprehensive care plan.

Northouse offers the construct of “leadership making” for developing high quality exchanges that help make all followers feel as if they are part of the in-group. This requires time as the leader-follower dyads move through three phases of forming a transformational partnership (Northouse, 2018). While a useful tool, the time it takes to reach this end goal would be expected to be much longer on a medical team due to the high turnover of team members.

Authentic leadership focuses on leadership that is genuine, honest, and good while building a sense of trust with the followers. Authentic leaders exhibit four core characteristics: self-awareness and the impact their actions have on others, an internalized moral perspective that resists outside negative influence, balanced processing that seeks and analyzes others’ opinions before making a decision, and relational transparency in presenting their true self to others. (Northouse, 2018). Physician leaders should understand these values and the positive influence of these behaviors toward others and the common good of the group. Authentic leadership can be learned and developed overtime, making it ideal for use on an inpatient medical team given the paucity of formal leadership training in medical schools.

“If your actions inspire others to dream more, learn more, and become more, you are a leader.” -John Quincy Adams

How to Develop an Inclusive Leader

Since leadership inclusiveness is integral to creating a welcoming work environment, which in turn will hopefully breed maximum efficiency and effectiveness, yet its tenets are not formally taught to most medical professionals, it is important to understand the characteristics of inclusive leaders such that these can be inwardly sought and explicitly practiced. Leadership inclusiveness has been associated with specific actions, behaviors, antecedents, and leader characteristics.Howard, et al. identify three specific physician leadership behaviors that exemplify leadership inclusiveness: explicitly soliciting team input, engaging in participatory decision making, and facilitating the inclusion of out-group members (Howard et al., 2012). As previously mentioned, medical team members (particularly those of lower perceived status) have numerous reasons for not freely voicing their opinions. Explicitly soliciting input in an inviting way is an effective and safe technique to gather the thoughts of each team member.

The contributions should be acknowledged and the team member thanked. In participatory decision making, the physician remains actively engaged in the decision-making process by sharing opinions and respectively challenging team members to reflect on the consequences of their decisions which leads to clearer and more rational group thinking. The inclusion of out-group members is important in a healthcare setting to achieve maximum team collaboration and downstream patient benefits.

Given the uncertainty and complexity surrounding inpatient medical care, Edmondson postulates that actions of followers in this type of environment require the specific behaviors of active learning, questioning, experimenting, seeking help, and feedback. These behaviors are accomplished through the following set of leader characteristics, which are antecedents to leadership inclusiveness (Edmondson, 2008), and can be practiced by any physician:

- Accessibility – freely invites questions, problems, and input. Encourages learning and is personally involved in the team.

- Acknowledging fallibility – followers may see the leader as infallible, yet this is certainly not true. A leader acknowledging their own vulnerabilities, mistakes, and actively soliciting feedback shows followers their input is respected and moves along the continuum of “leadership making” toward a transformational partnership.

- Maintaining accountability – maintaining inclusiveness does not mean that quality and accountability are sacrificed, rather expectations are clear and people are not punished for asking for help or humiliated for an error.

- Setting goals – setting clear and defined goals help team members develop a sense of autonomy and group cohesiveness while successful goal accomplishment enhances self-worth and job satisfaction.

“Coming together is a beginning, staying together is a process, and working together is success.” -Henry Ford

The Optimal Distinctiveness Theory postulates that members will feel included in a group when they are afforded high levels of belongingness and uniqueness (Shore et al., 2010). According to Swanson, this is done by leaders expanding their perspectives to not only understand but also appreciate others through staying in the present, increasing comfort level with ambiguity, decreasing distortion, and choosing actions that support the desired outcomes (Swanson, 2004).

Ideally, a culture of inclusion would be built into each individual medical team and the larger healthcare system as a whole. This panacea for inclusion would be composed of an inclusive climate, leaders, and general practices (Shore et al., 2010). An inclusive climate strives for fairness and celebrates diversity while inclusive practices help members feel as if they belong yet retain their individual uniqueness.

Psychological Safety is Positively Associated with Leadership Inclusiveness

When leaders demonstrate inclusiveness through the aforementioned leadership theories and methods, those of lower perceived status (the non-physician medical team members) will feel supported and valued as a team member. In this manner, leadership inclusiveness is a precursor to, and positively associated with, psychological safety, which is defined as “being able to show and employ one’s self without fear of negative consequences of self-image, status or career”.Psychological safety on a medical team is generally perceived on an individual level, although group level (and to a lesser extent organizational level) psychological safety has been described (Newman et al., 2017). Numerous key antecedents have been strongly associated with the attainment of psychological safety. These include proactive personality, emotional stability, openness to experience, learning orientation, autonomy, role clarity, interdependence, and peer support (Frazier et al., 2016). These are all positively affected by positive leader relations developed through leadership inclusiveness.

Putting it All Together for Improvement in Performance and Outcomes

The attainment of these antecedent qualities leads to numerous positive outcomes. In this way, psychological safety acts as a mediator between leadership inclusiveness and development of a desirable work environment, employee satisfaction, and performance. Psychological safety is the mechanism by which supportive environments transmit desirable outcomes (Newman et al, 2017). Specific individual level outcomes that have been shown to be strongly associated with psychological safety include work engagement, task performance, information sharing, creativity, learning behaviors, commitment, and satisfaction (Frazier et al., 2016). On the other hand, a lack of psychological safety has been associated with emotional exhaustion, burnout, poor job satisfaction, and lack of organizational commitment/intention to find new employment (Manser, 2008).

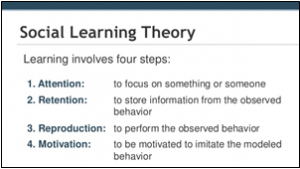

Two main theories describe how psychological safety develops and influences work outcomes: social learning theory and social exchange theory (Newman et al., 2017). Social learning theory is a theory of learning and social behavior that postulates new behaviors can be acquired cognitively by observing and imitating others. Leaders who engage in active listening, forwarding support, and providing clear and consistent directions to followers are able to show followers that it is safe to take risks and engage in honest communication, which followers then start to emulate. Social exchange theory is based on a process of negotiated exchanges between the leader and followers such that when followers are supported by the leader, they will reciprocate with supportive behaviors themselves, creating a psychologically safe environment (Newman et al., 2017). Because they are built through learning and emulation, rather than point-in-time exchange, outcomes formed via social learning theory are felt to be stronger and longer lasting (Newman et al., 2017).

When investigating these two social theories link to leadership theory, it becomes clearer why social learning theory would be more influential and enduring. Social learning theory is more akin to Transformational Leadership, whereby leaders act as strong role models with high standards of moral and ethical conduct who listen closely to follower needs and help actively shape and inspire them to become committed to the team. Social exchange theory is more transactional in nature in that processes are negotiated and may be more reactive. This does not necessarily focus on the active personal development of the followers. Social learning theory also holds more of the constructs described in change-oriented leadership, which includes analyzing information in the external environment to identify threats and opportunities for the team, encouraging innovative thinking, envisioning and proposing change with enthusiasm and conviction, and taking personal risks to promote desirable change. These factors have been shown to be transformational in developing team learning behavior and enhancing team performance (Ortega et al., 2013) – all through the tenets of leadership inclusiveness and psychological safety.

Personal Experiences and Advice

I think that in many ways I exhibit some principles of the Behavioral Approach, Leader-Member Exchange, and Authentic Leadership each day when leading an inpatient medical team. I have come by these styles both through my natural personality characteristics and observing/learning from physicians with more clinical experience.I think that establishing a culture of psychological safety is something to which certain practitioners may be more naturally inclined based on personality. If a leader takes an authoritarian, unsupportive, or defensive stance, team members are more likely to feel that speaking up in the team is unsafe. In contrast, if a leader is democratic, supportive, and welcomes questions and challenges, team members are likely to feel greater psychological safety in the team and in their interactions with each other (Nembhard and Edmondson, 2009). I strongly self-identify with the latter.

Developing a culture of psychological safety is also something that can be learned, practiced, and improved upon.

The previous sections describe how to develop an inclusive leader, and although some people may be more naturally inclined, these are skills that all physician leaders can attain. I have made concerted efforts to solicit team input, engage in participatory decision making, and facilitate inclusion of “out-group” members and do so in a manner that is welcoming and professional. These methods help people believe that their voices are genuinely valued. Without a recognizable invitation, impressions derived from the historic lack of invitation will prevail (Nembhard and Edmondson, 2009). Furthermore, I have learned that to create a truly transformational medical team culture, appreciation of everyone’s role and ideas is equally important. Without appreciation (i.e., a positive, constructive response), the initial positive impact of being invited to provide input will be insufficient to overcome the subsequent hurdle presented by status boundaries (Nembhard and Edmondson, 2009).

The innumerable interworking dynamics of an inpatient medical team are complex and ever changing. However, these principles of leadership inclusiveness and psychological safety are unwavering. When implemented thoughtfully and correctly they provide a sense of constancy and help the team achieve universal cohesiveness and goals that may have previously been thought impossible.