Main Body

Chapter 2 Turkish Classical Music & Instrumentation: A History in the Sound of Music

by Noah Bayindirli

Music in Turkey produces familiar tones in the modern day, but its origins and past implementations may come as a surprise to some. Throughout the ages, Turkish music has grown and transformed dramatically, influencing issues as diverse as religion, social interaction, politics, and civil disobedience. From the late Ottoman Empire to Atatürk’s Republic, or even among the vast collection of instruments and its impact on musical structure, Turkey has truly had its hand in every facet of this art form. Provided this immense face of Turkish culture, this chapter focuses on classical Turkish music and its development, beginning in the Ottoman Empire.

Turkish music as we know it today has its roots in the period of Ottoman rule. Although the majority of its development took place under the reign of the sultan, the sound of Turkey was greatly influenced by surrounding cultures and their musical traditions. These include the Arabs, Persians, and even the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) churches of Istanbul, bringing with them their musical techniques and methodologies.

Initially a courtly art, classical music existed mainly within the walls of the Ottoman palace. Classical music eventually moved out and into the streets of the empire. From performances within the royal harems—for women, by women—these practices made their way to the public via male street performers, or rakkas. While their movements were part of the “belly dancing” canon, rakkas utilized the Çiftetelli rhythm and played zils (finger instruments) masterfully to accompany their dance. These dancers took this music, technique, and performance to a variety of celebrations in Turkey, including feasts, weddings, and festivals.

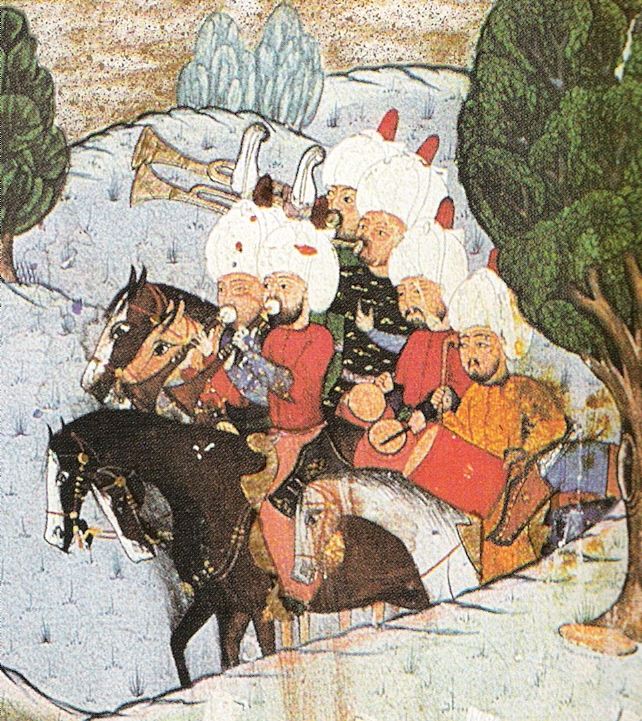

A further implementation of music within the Ottoman Empire is that of the Mehter, or Ottoman military band, which utilized kös drums and zurnas (a relative of the oboe) to follow the army into battle and instill strength and courage through sound. These bands served as a symbol of sovereignty and independence for the empire and followed the Çorbacibasi, or band commander.

Along with the significant impact of courtly sensibilities on the development of Turkish music, it encompasses a rich variety of folk traditions. From the classical çeng, reminiscent of an open harp, to the folk Kabak Kemane, or “gourd fiddle”, Turkish folk instruments vary greatly in size, shape, sound, and style. With this incredible array of instruments comes a notable collection of musical types and patterns.

The principle of makam, loosely understood as a rule of composition, profoundly shaped Turkish music theory. It is a musical scale progression creating patterns of note, scale, and structure. Although there are hundreds of makams, many common to Central Asia and the Mediterranean region, very few are formally defined. Interestingly, Sufi teaching describes each makam as representing and conveying a particular psychological and spiritual state.

Folk music typically falls into two forms: songs (lyrical) and melodies (instrumental), with a variety of sounds from Anatolia and Thrace. There are typically two main kinds of artists: Türkü singers and the Âsik, bards or minstrels. Although both types of musicians play and sing songs, Türkü typically perform their music anonymously and for a local audience, building off other artists and changing the pattern and words as they go. In contrast, Âsik utilize their own and other Âsik lyrics, producing sounds outside of the local music culture of where they currently perform. As a result, their music is typically personalized by their own style, voice, and experiences along their travels.

The final noteworthy type of music is that utilized by the whirling dervishes, who practice a form of Sama, or “listening,” known as Sufi whirling. During this form of active meditation, followers spin in circles while others sing and play instruments, in order to imitate the planets, abandon their egos, focus on God, and reach Kemal (perfection).

The journey through Turkish classical music would not be complete without a look at Atatürk’s utilization of the art form in his attempt to westernize the Republic of Turkey. During this movement in the early 20th century, Atatürk first changed the location and names of iconic music groups of the nation. For example, the Imperial Orchestra was relocated from Istanbul to the now-capital Ankara and renamed the Orchestra of the Presidency of the Republic; the Istanbul Oriental Music School employed western-style music teachers and was renamed the Istanbul Conservatory.

In addition to the establishment of orchestras and conservatories, Atatürk utilized technology to institutionalize Turkish music traditions. He implemented wide-scale classification and archiving of folk music samples from 1924-1953 and founded the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT). Through this state radio provider, the people of the Republic were able to find common ground with news, music, and television, and the effect of westernization was able to travel farther and faster throughout Turkey.

In sum, this chapter shows how the musical developments of classical courtly styles, folk traditions, military band music, sufi musical practices, and a rich assortment of instruments set the groundwork for a broad range of music and social movements in today’s Republic of Turkey.

Works Cited

“History.” Turkish Classical Music, Turkish Cultural Foundation, www.turkishmusicportal.org/en/types-of-turkish-music/turkish-classical-music-history.

“Makams.” Turkish Classical Music, Turkish Cultural Foundation,

http://www.turkishmusicportal.org/en/types-of-turkish-music/turkish-classical-music-makams.

“The Makam Phenomenon in Ottoman Turkish Music.” Turkish Classical Music, Turkish Cultural Foundation,

“Forms.” Turkish Folk Music, Turkish Cultural Foundation,

http://www.turkishmusicportal.org/en/types-of-turkish-music/turkish-folk-music-forms.

“History.” Turkish Folk Music, Turkish Cultural Foundation,

http://www.turkishmusicportal.org/en/types-of-turkish-music/turkish-folk-music-history.

“Instruments.” Turkish Classical and Folk Music, Turkish Cultural Foundation,

http://www.turkishmusicportal.org/en/instruments.

“Music of Turkey.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 29 Oct. 2017, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_of_Turkey.

“The National Anthem.” Turkish Cultural Foundation, Turkish Cultural Foundation, www.turkishculture.org/music/marches-and-anthem-35.htm.

“Military (Mehter).” Turkish Cultural Foundation, Turkish Cultural Foundation, www.turkishculture.org/music/military-mehter-86.htm.

“Sufi whirling.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 17 Oct. 2017, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sufi_whirling.

“Turkish Radio and Television Corporation.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 14 Oct. 2017, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkish_Radio_and_Television_Corporation.

“Turkish Five.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 17 Oct. 2017, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkish_Five.