Main Body

Chapter 7 Turkish Literature Through the Ottoman Empire

By Ashley Clark

Early Writings

Turkic literature spans approximately 1,300 years. The earliest known writings in a Turkic language (see the Introduction on Turkish linguistic roots) are the Orhan (Orkhon) Inscriptions, discovered in the valley of the Orhan River in Northern Mongolia in 1889. The two large monuments date to 735 CE and 732 CE. They were made to honor Turkish Kül ‘Tigin’ (prince) and Bilge ‘Khagan’ (emperor), two brothers. The advanced style of writing suggests that there were earlier developments of the written language.

Oral tradition was the prominent early form of Turkish literature between the 9th and 11th centuries. The most popular genre at that time was the epic, such as the Book of the Dede Korkut of the Oghuz Turks (details, below), one of the cultural and linguistic ancestors of modern Turks.

Only after the Seljuk victory in the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 CE, when they began to settle in Anatolia, did written literature become prominent. Written literature was largely influenced by Arabic and Persian literature until the Republican era, when Atatürk expunged the Turkish language of most Persian and Arabic influences. Until the fall of the Ottoman Empire, written and oral literature were two separate entities.

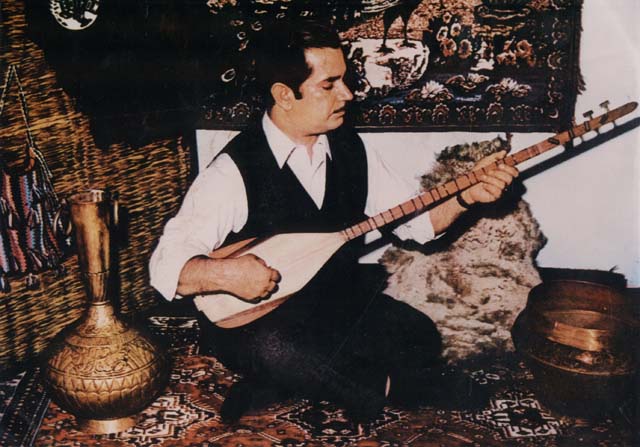

Folk Literature

Folk literature was rooted in the nomadic lifestyle, primarily composed of oral tradition, and was typically intended to be sung. Sometimes performers would be accompanied by an instrument such as a saz (lute). Much of the oral tradition and folklore were centered on storytelling. Some of the primary genres that grew out of folk literature were epics, legends, folktales, fables, proverbs, anecdotes, and minstrel music.

The most prominent epic to have come out of Anatolia was The Book of Dede Korkut, (Dede means Grandfather), written in Oghuz Turkish. This epic was primarily performed by Âşiks, Oghuz Turkish poet-musicians. They were performers who sang epics along with other poems and lyrical songs. The Book of Dede Korkut has survived through two 16th century manuscripts. It was circulated centuries prior to these manuscripts, but the exact date of its origin is unknown.

A very important character in Turkish folk literature is Nasreddin Hoca (pronounced “Hoja”), a folk philosopher, comedian, and trickster. He represents the “indomitable spirit of the common people” (“Turkish Language & Literature”). Little is known about his life. However, he probably lived in the 13th century. He served as a religious teacher, preacher, and judge. For centuries, he has remained a prominent character in both Muslim and non-Islamic communities in the Middle East. His wit transcended national and cultural borders, as his stories have been translated into many languages, attesting to his universal appeal.

Folk Literature vs. Ottoman Literature

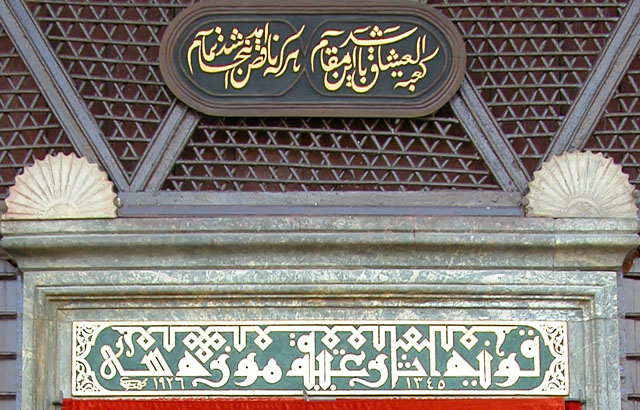

The literature created for the consumption of the Ottoman Sultan and nobility, or Ottoman literature forms the basis of formal Turkish literary aesthetics. Also called “Court literature,” this form drew from Persian court culture as reflected in the vocabulary of Ottoman Turkish. Ottoman Turkish is quite distinct from modern Turkish because it incorporated many more Persian and Arabic vocabularies. The Persian words tended to relate to court life, poetry, and fine arts.

Folk literature remained primarily separate from Ottoman literature, as an oral tradition. Ottoman literature, in contrast to Folk literature was also a written form throughout almost the entire duration of the Ottoman Empire. This was in part an expression of its formality. It was written in the Arabic script, a mode which Mustafa Kemal Atatürk did away with under his modernizing reforms. Another difference between the two is that folk literature was primarily structurally comprised of quatrains (lines of four verses), while Ottoman literature was composed of couplets (lines of two verses).

This systematic difference in writing and delivery method between folk and Ottoman literature in effect separated people within the Empire into literate and non-literate, upper and lower, classes. The one thing that these two forms of literature had in common, however, was musical performance, which eventually brought the two genres together just before the fall of the Ottoman Empire. During the 17th century, traveling minstrel music, or the music of the âşik, became a bridge between the court and the people.

Sufi Poetry

Sufi poetry is another major cultural influence on Turkish literature, dating back to the 11th and 12th centuries. It became a major branch of Turkish literature in the 13th century. Sufi mystics expressed their love and devotion to God through their poetry. Âşık Paşa and Yunus Emre were the most prominent Sufi poets of the 13th and 14th centuries. Âşık Paşa wrote Garībnāmeh (“The Book of the Stranger”), which comprises 11,000 couplets and is known as one of the finest mesnevîs (rhyming couplets that usually have spiritual meaning related to Sufism).

Yunus Emre, born in Eskisehir, is one of the most influential sufi poets in Turkish literature. He wrote the prominent, Risâletʿün nushiyye, “Treatise of Counsel”. His poetry often took the form of love poetry but with a twist, the “Beloved” he mentioned was a reference to God. The following sample (Smith, 1993) demonstrates this way of writing about love:

“O man of love, open your eyes; look at the face of the earth. See how these lovely flowers, bedecking themselves came and the passed on.

These, bedecking themselves in this way, stretching out toward the Beloved – ask them, Brother, where are they going.

Every flower, with a thousand coquettish airs, praises God with supplications.” (p. 12)

His writings today remain central to the dhikr, or chanting, practiced by tarikas, or Sunni brotherhoods, and to the ayîn-i cem ritual of the Alevî Bektashi, an order of tribal Shīʿite Sufis.

Rumi is another very prominent Sufi scholar and poet, who is now world-renowned. He was born in Balkh (in modern-day Afghanistan), and lived the majority of his life in Konya, Turkey, where his is buried. A prominent work of his is The Mathnawī and Diwan-e Shams-e Tabriz-I.

Divan Poetry and Classic Turkish Literature

As mentioned, Ottoman literature was primarily produced in the written form with a great deal of influence from both Arabic and Persian. Divan poetry is a significant example of this form of Ottoman literature (Mesnevi and Qasida) was the most prominent form of Ottoman literature. Mesnevi and Qasidas were most prominent in early Ottoman history, but in later Ottoman literature new genres came to the forefront such as biographical dictionaries (tezkires), urban song (şarkı), and tâze-gûʾî (“fresh speech”).

Qasida ( or Kaside) are praises, either of God or a leader (like the Prophet Mohammad, the Sultan, or a military leader). These were long and comprised of various sections. Gazel poetry was often sung and accompanied by instruments. The poetry was composed of couplets and the theme was usually love.

Ottoman poetry of the 15th and 16th centuries represent a fusion of the three major Islamic languages—Turkish, Persian, and Arabic. In the 17th century, Mesnevis were on the decline. Some prominent names from Ottoman literature include (in addition to the Sufi poets mentioned) Hayali Bey, Mahmud Abdülbâkî (also known as Bâkî), Cevri and Neşatî (the leaders in the form of “fresh speech”), Nâbî (whose most prominent work is the mesnevi), Hayrîyye, Âşik Ömer (a prominent âşik of the later 17th century), and Şeyh Galib (1782; mesnevî Hüsn ü aşk translates to “Beauty and Love”, was one of the most prominent works of late Ottoman Literature). Beauty and love were prominent themes.

The 19th Century and Western Influence

In the 18th century, there were many great changes in style and with the genesis of Western influence. The Tanzimat Period (1839 – 1876 CE), brought many reforms in Ottoman society, culture, and government, which affected the literature. By 1859, İbrahim Şinasi completed the first theater play, his stage comedy Marriage of a Poet, or Şâir Evlenmesi (Turkey Music Lit, n.d.). By 1860 the literary format of the novel “first appeared in Ottoman cities” (Göknar, 2008, p. 472). These Western forms took on a unique Turkish form, however, as they integrated the three aforementioned folk, Sufi, and Ottoman forms of literature and oral tradition (Göknar, 2008).

Major changes associated with movements toward a Turkish national identity shaped Turkish literature of the early 20th century, and continued evolving as a result of the “linguistic engineering” (Göknar, 2008, p. 474) which occurred during that time. The alphabet was changed as part of this in 1929 from Arabic to the Roman alphabet. These reforms represented a break from the Ottoman past as part of a turn to the West and a national commitment to modernization. Yet, the definition of modernization wasn’t to be determined by simple East/West, traditional/modern binaries. Novels, short stories, and other modern formats, published throughout the rest of the 20th century until today reflected and contributed to a modern Turkish identity shaped by multiple, uniquely Turkish, internal discourses (Göknar, 2008).

Bibliography

Images

Orhan Inscriptions image: By Vezirtonyukuk – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44739097

Map: By DragonTiger23 – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11649848

Nasreddin Hoca: “Nasrettin Hoca5”. By: archer10 (Dennis). Flickr. CC2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nasrettin_Hoca5.jpg

Asik: “Asik daimi 3” By Ecomecom. Wikimedia commons. CC2.5. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Asik_daimi_3.jpg

Ottoman Divan: “Fuzuli Divan”. Unknown author. Wikimedia Commons. CC0/ Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fuzuli_Divan.jpg

Works cited:

Feldman, Walter. “Turkish Literature”. Encyclopedia Brittanica, Encyclopedia Brittanica, 07 December 2017. Web. https://www.britannica.com/art/Turkish-literature

“Orkhon Inscriptions”. Wikipedia, Wikipedia, 07 December 2017. Web. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orkhon_inscriptions

“Turkish Literature”. Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Kultur.gov.tr, 07 December 2017. Web. http://www.kultur.gov.tr/EN,117851/turkish-literature.html

“Turkish Literature”. Wikipedia, Wikipedia, 07 December 2017. Web. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkish_literature

“Turks Literature”. Turkish Cultural Foundation, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey, 07 December 2017. Web. http://www.turkishculture.org/literature-473.htm

Smith, Grace Martin (1993). The poetry of Yūnus Emre, a Turkish Sufi poet (0-520-09781-5, 978-0-520-09781-0). Berkeley :: University of California Press,.

Kasaba, R. (2008). Turkey in the modern world. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Göknar, E. (2008). The novel in Turkish: Narrative tradition to Nobel prize. In R. Kasaba (Ed.), The Cambridge History of Turkey (Cambridge History of Turkey, pp. 472-503). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521620963.018

Turkey | Music, Literature, Dance And Fashion – 1800 – 1930. (n.d.). Retrieved October 15, 2018, from http://sharinghistory.museumwnf.org/hcr_result.php?begin=0&startPeriod=Before+1800&endPeriod=After+1930&nccountry=tr&theme=9