Main Body

Chapter 5 Turkish Arts

by Ashley Clark

Turkish Rugs

Rug weaving represents a significant portion of Turkish aesthetics and material culture, with a continuing tradition of carpet-making since the time of the Turkic migrations from Central Asia that originally brought Turkish culture to Anatolia. The oldest surviving examples of original Turkish rugs are from the Seljuk Period in the 13th century, immediately prior to the Ottomans coming into power in Asia Minor. Girls were taught to weave these carpets as a form of education and upbringing, to prepare them for entering womanhood. They could express their creativity and imagination through carpet weaving. Popular imagery focused at first on animal motifs, then the imagery evolved into very ornate geographic patterns.

The second major era of rug weaving began in the 16th century with the Ottoman Turks. These rugs were functional, used for everything from wedding ceremonies to tombs.

Today, rug weaving is a diminishing practice in Turkey. Only 20% of rugs sold in the Grand Bazaar were actually made in Turkey, some imported from China among other places. There are currently no new carpet weavers and people worry that the trade could die off in about 20 years. The industry itself is becoming less profitable as fewer people are purchasing carpets.

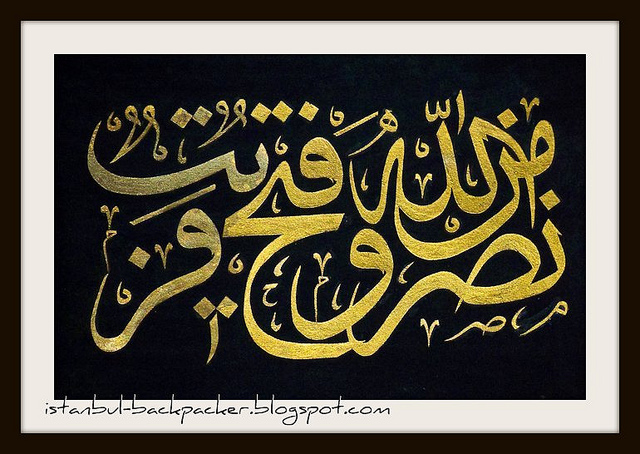

Calligraphy

Calligraphy is not actually of Turkish origin, but the Ottomans adopted it and made it uniquely their own. Calligraphy was written in the Arabic script and reeds were used to write and draw with ink. Calligraphy had the ability to transform any mundane document, such as tax receipts and legislature, into a work of art. Calligraphy not only involved a fluid representation of words, but also included creative forms, taking written words and rendering them into images (such as the lion image below).

During the Republican period, calligraphy began to die out. This may have been due in part to the language reform and introduction of the Latin alphabet, the goal of which was to Westernize the language while also making it correspond with Turkic vocabulary. Thus, the Persian and Arabic language influence was diminished, along with their aesthetic influences.

undefined

Miniatures

Miniatures are paintings used to accompany a text that tells a story, from folk narratives to biblical tales. Miniatures reflected the daily life and folklore of people across cultures. Turkish miniatures reached their peak in the 16th century. These works were typically anonymous.

Ebru

Ebru is a technique where pigments of color are placed on oily water and manipulated to create images and paintings. Once the marbled painting is completed to the artist’s desire, a paper is placed onto the oily surface of the water, soaking up the pigment into the sheet of paper. Then the artist gently lifts the paper off of the water and leaves it to air dry. Ebru was invented in 13th-century Turkistan; from there, it migrated to Anatolia where it was adopted by both the Seljuks and the Ottomans. Floral imagery, especially tulips, abstract shapes, and other images are very popular motifs. These paintings are used to decorate books and documents and the art form is still alive and thriving today.

Westernization of Turkish Arts

Westernized Turkish painting only began in the 19th century with the founding of the Academy of Fine Arts by Osman Hamdi Bey. The Sultan sent Turkish painters to France and Italy to learn Western techniques; meanwhile, foreign painters were brought from Europe to share their skills. In the 20th century, many artistic movements began in Turkey with various groups of artists returning from Europe.

The 1914 Generation was a group of students sent to study art in Europe around 1908 – 1910, that was forced to return to Turkey in 1914 due to WWI. When they returned, they brought back European impressionism and so they were known as the ‘Turkish Impressionists’. More emphasis was placed on lightness, color, shape, and design. Impressionist paintings were primarily composed of landscapes, portraits, nudes, and daily life.

The first community of artists in Turkey were called the ‘Independents,’ or the ‘Union of Independent Painters and Sculptors.’ These were students who studied art in Europe in the 1920’s, returning to Turkey with the influence of Fauvism, Cubism, and Expressionism.

Another contemporary movement of Turkish painters was ‘Group D,’ founded in 1933 and very influential in the Turkish art community well into the 1980’s. These artists utilized post-Cubism and stressed composition over construction. Group D accelerated the process of modernization and Westernization in Turkey.

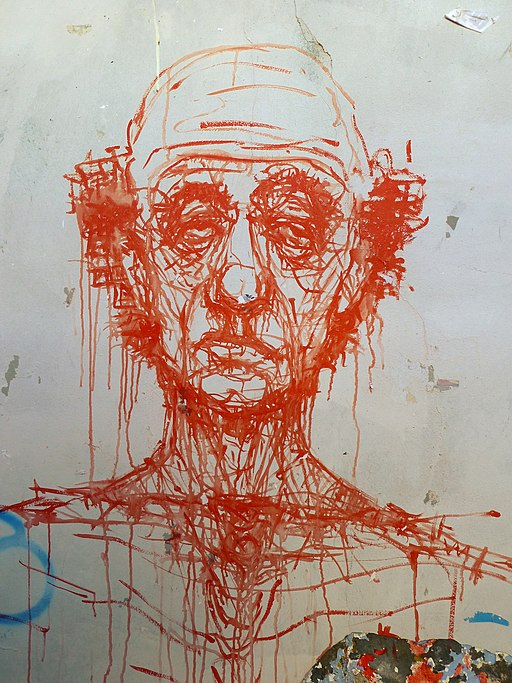

Graffiti and Street Art Graffiti, Paint, Photography, Travel, Background, Wall

Graffiti began in Istanbul in 1984 with Dunc “Turbo” Dindas, known as the father of Turkish graffiti. He began making street art and graffiti after watching the American film Beat Street, a movie about street art in New York City. There was some controversy after Turbo began spray-painting the streets of Istanbul; some were upset while others supported the new artistic style.

This form of art exploded in 2013 in response to the Gezi protests and police brutality. Protestors were against the government’s plans to privatize a public park in the center of Istanbul, Gezi Park. They rallied opposition in what became known as the Gezi protests. Protesters were met with tear gas and brutality from local enforcement. As a result, graffiti and street art became a popular form of expression to display citizen’s dismay with the tragedy of events and the government. People spray painted phrases targeted at the police and government or images of brave protesters.

Kadikoy’s Yeldegirmeni district became a popular place for graffiti after the Gezi protests. The Istanbul art scene grew very much out of the Gezi protests, not only through graffiti; art galleries saw a rise in attendance after the protests.

Bibliography

Rigney, Robert. “The Carpets of Turkey”. The Islamic Monthly, The Islamic Monthly, 21 March 2017. Web. https://www.theislamicmonthly.com/the-carpets-of-turkey/

“Discover the soul of Metropolis Life in Turkey through Street Art”. Turkey.com, Turkey.com, 07 December 2017. Web. http://turkey.com/home/culture/arts-design/street-art/

Hartley, Morgan and Walker, Chris. “The Father of Turkish Graffiti”. Forbes, Forbes. 23 August 2012. Web. https://www.forbes.com/sites/morganhartley/2012/08/23/the-father-of-turkish-grafitti/#6133215046b6

Shafak, Elif. “Smiling Under a Cloud of Tear Gas: Elif Shafak on Istanbul’s Streets”. Daily Beast, TheDailybeast.com, 11 June 2013. Web. https://www.thedailybeast.com/smiling-under-a-cloud-of-tear-gas-elif-shafak-on-istanbuls-streets

Sansal, Burak. “Turkish Arts”. All about Turkey, Burak Sansal, 07 December 2017. Web. http://www.allaboutturkey.com/art.htm

Sansal, Burak. “Ebru Art”. All about Turkey, Burak Sansal, 07 December 2017. Web. http://www.allaboutturkey.com/art-ebru.htm

“Turkish Art”. Wikipedia, Wikipedia, 19 October 2017. Web. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkish_art

Yenen, Serif. “Turkish Period”. Turkish Odyssey, Turkish Odyssey, 07 December 2017. Web. http://www.turkishodyssey.com/turkey/history/turkish-period

“The Turkish Art of Marbling: Ebru”. Turkish Cultural Foundation, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey, 07 December 2017. Web. http://www.turkishculture.org/traditional-arts/marbling-113.htm

“Turkish Miniatures”. Turkish Cultural Foundation, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey, 07 December 2017. Web. http://www.turkishculture.org/traditional-arts/miniatures/life-in-istanbul-785.htm?type=1

Bored Panda Art. “Turkish Artist Paints On Water Using One Of The Oldest Turkish Art Techniques Called Ebru”. Youtube, Youtube, 01 July 2016. Web. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ky-07DkBmvk

Images

Rug weaving image: “One of a Kind”. Nick Allen. Flickr. C.C. 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nickallen/3807092914/in/photostream/

Painting featuring Anatolian rugs: “The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius – Carlo Crivelli – National Gallery”. By Carlo Crivelli – National Gallery, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41347574

Rug: “Re-entrant prayer rug Anatolia late 15th early 16th century reverse”. Anonymous. Wikimedia. Public Domain CC 0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Re_entrant_prayer_rug_Anatolia_late_15th_early_16th_century_reverse.jpg

Calligraphy tools image: “Little world, Aichi prefecture – Turkish culture exhibition – Pens for Hat (Turkish calligraphy) & Presidential envelope”. By Yanajin33 – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29911164

Calligraphy: “Meşk (calligraphy exercise)”. Abdurrahman Hilmi 1805 at Google Cultural Institute, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22883825

Miniature: “Workshop of the Turkish miniatures” By Unknown – Own work, scanned by Szilas from Török miniatúrák by Géza Fehér, Corvina 1978, Budapest, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23255129

Ebru person: “Technique de l’ebru (2)” By Ji-Elle – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22072695

Ebru: “Technique de l’ebru (7)” By Ji-Elle – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22072702

Painting (early 20th century): “The Tortoise trainer”. Osman Hamdi Bey. Wikimedia. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Osman_Hamdi_Bey_-_The_Tortoise_Trainer_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

Painting: “Manzara” (1898) By Hoca Ali Rıza – http://www.sanalmuze.org/sergiler/contentz.php?imgid=3380&ic=75&sergi=556&pg=0&order=2&act=next at Eczacıbaşı virtual museum, Kamu Malı, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9695095

Graffiti Image: Untitled. Engin_Akyurt. Pixabay. CC0. https://pixabay.com/en/graffiti-paint-photography-travel-2387521/

Graffiti Photo: “Graffiti 1250233”. Nevit Dilman. Own Work. CC3.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Graffiti_1250233.jpg