Module 1: Goals for Studying Grammar

Module 1: Advanced Unit

GOALS FOR STUDYING GRAMMAR

Contents of Advanced Unit:

1. Tools for grammatical description

We have established that our goal is a descriptive account of the grammar of English: the rules that native speakers know as part of their internal knowledge, which govern their production and interpretation of sentences. In this unit, we’ll talk a little more about what it means to have a grammatical description, and introduce some of the tools we will use to conduct that description.

How many sentences do you think are possible in English?

Trick question! There are an infinite number of possible unique English sentences. This is in fact one of the features that distinguishes human language from animal forms of communication: it is possible to generate an uncountable number of novel sentences to express an uncountable number of meanings. How can we possibly begin to describe, then, all the sentences an English speaker could produce?

Just as when describing any complex system, we will focus on patterns and abstractions. Rather than developing a rule that describes one single sentence, we want rules that will account for any possible sentence in English—and that will rule out the sentences that aren’t possible.

I bet you can do this for a very simple rule right now, with only the existing knowledge you have about grammar. Write a rule that explains why (1-3) are grammatical in English, but (4-5) are not. Note that the asterisk means something is ungrammatical; this is a convention within linguistics.

(1) the dogs

(2) the dog

(3) the cat

(4) *cat the

(5) *dogs the

(1-5) all contain different combinations of words. How can one rule explain them all? I bet that your rule did not include the word cat, dogs, or dog; rather, I bet you lumped all these items under the same category NOUN (or something similar based your previous schooling). The system of a language is made up of patterns, and to explain them, we want abstract rules. Any given phrase or sentence can be seen as an instantiation of abstract rules involving abstract categories.

Ultimately, we want to be able to explain the maximum number of possible sentences with the minimum number of possible rules. There will always, however, be exceptions—please do not be frustrated by this!

So one tool that we will use to talk about language at an abstract level are categories, like the category introduced above, NOUN. We will deal with categories at the level of words, phrases, verbs, and other grammatical units. It is important to keep in mind that these categories always represent generalizations: our attempts as humans to analyze the natural system of language in an efficient way. As said earlier, languages do not come with ready-made analyses, and everything doesn’t always “fit” as neatly as we might like. This is all part of the fun of exploring language through a descriptive, explanatory lens.

Another tool that we will use are visual diagrams of sentence structure. We will use a system of sentence diagramming called phrase structure trees, though because of the title of this textbook, you are free to call them ELLM trees! Trees are a way of showing visually our analysis of a sentence and its hierarchical structure. We’ll introduce trees that represent specific rules later on; for now, I just want you to have some sense of why trees are useful modes of representation.

Consider the following sentence:

What is the meaning? You will probably get two different possible interpretations of this sentence, represented by the two pictures below.

In one interpretation, the broccoli is on the pizza. In the other, the broccoli is a side dish. Both are plausible, linguistically and gastronomically. This is an example of linguistic ambiguity, and illustrates why we need to think of language hierarchically: If sentences were interpreted simply as a matter of the linear order of words, it should not be possible to derive two different meanings from the same sequence of words.

Now consider the two ELLM trees below. Don’t worry about the labels yet, just focus on the structure. What do you think is different between them? See if you can match them to the meanings from the pictures above. (These trees are drawn with the excellent tree-drawing online tool created by Miles Shang and available here: http://mshang.ca/syntree/)

The first tree means the broccoli was a topping on the pizza; the second tree means the broccoli was a side dish. The crucial issue is what unit with broccoli relates most centrally to: the pizza, or ate the pizza? I hope you can see how the trees show a difference between these, and how they illustrate the hierarchical relationships between grammatical units.

There are ways to diagram sentences that aren’t tree-like, and I would be remiss if I did not at least mention them. Aside from trees, probably the most popular is a Reed-Kellogg diagram. Here is a very detailed explanation of them from the textbook Grammar Alive! A Guide for Teachers (Brock Haussamen et al.), in case you are interested (looking at this is totally optional):

Reed-Kellogg diagrams from “Grammar Alive!”

I am not trained in how to diagram sentences this way. I tried to diagram the two versions of our test ambiguous sentence about pizza and broccoli and came up with these. Can you tell which diagram is supposed to represent which interpretation?

I leave it to you to investigate these diagrams more if you are interested (there are plenty of grammar textbooks that use them). As far as I can tell, there are certain things R-K diagrams and trees do equally well: representing the subject and predicate (as it is traditionally called), for instance. There seem to be other things R-K diagrams do less well, like showing at a glance the internal structure of complex noun phrases. There may be some things R-K diagrams do better, like representing clearly the head of a phrase (we’ll talk about all of this soon!). The point is just that using either system is a choice; there is nothing inherent about studying grammar that requires either. If you are ever going to teach your own grammar class, you will have to choose to one of these systems, another diagramming system, or no diagramming at all. All have benefits and limitations.

I choose phrase structure trees because they reflect my own training as a linguist, because reading the linear order of a sentence from them is clear (I find reading R-K diagrams to be a headache!), and because they encode what I believe is the fundamentally hierarchical property of language: that smaller units of meaning join together to form larger units of meaning.

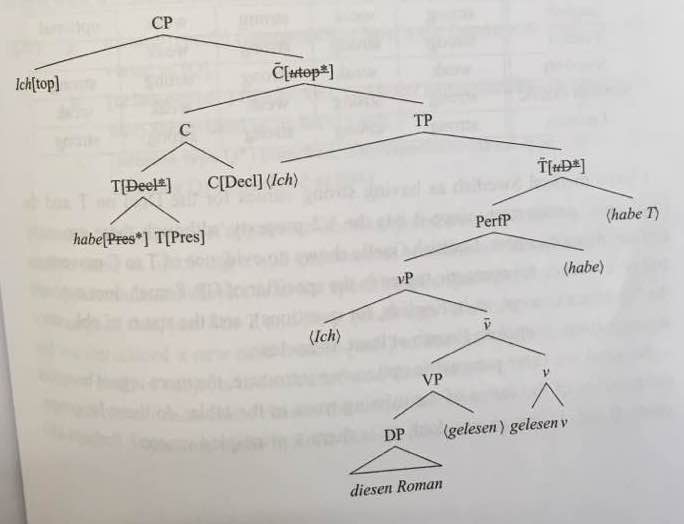

However, if you ever take a formal/theoretical syntax class, you may be surprised by some of the trees you see there, compared to our trees. For example, the following tree comes from David Adger’s textbook, Core Syntax: A Minimalist Approach (p. 331).

Formal syntacticians are trying to do something related to our goals, but slightly different. In addition to being able to describe the set of patterns that makes up English grammar, they are also trying to account for a) the computational apparatus in speakers’ minds that allows all language to be possible, which means b) universal patterns of grammar that cut across all languages. Theoretical syntax trees thus represent attempts to go beyond what is found in the surface of English sentences, and move to a deeper level of hypothesized structures that all humans share. This approach is rooted in the insights of linguist Noam Chomsky in the 1950s, and much (but certainly not all) of modern linguistics shares some of his assumptions.

Once we get to more complicated sentence structures, we will also start to see some of the limits of trees to describe English using only what’s on the surface. We will talk about these issues, and the assumptions underlying how we use trees for these more complicated structures, as they come up.

2. Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 1, Advanced Unit

Complete before moving on to the next unit!