Module 7: Meaning and Structure of/in Verb Phrases

Module 7: Basic Unit

Contents of Basic Unit:

- Predicators and complements

- Basic clause functions and verb types: intransitive, transitive, ditransitive

- Predicative complements: nouns, adjectives, and prepositions

- Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 7, Basic Unit

1. Predicators and complements

By now you should be VERY familiar with the fact that verbs are an essential element of a sentence. Verbs create the requirement for a subject–you can’t interpret a command as subjectless, no matter how hard you try!–and verbs predicate something of that subject. In this chapter we will get a little more technical about what verbs do, and how verb phrases are structured. Much of the rest of the semester will be spent exploring different kinds of verbs and how they build differently-structured sentences.

We will begin by building on our understanding of predication.

First, let’s consider two different verbs: cough and acknowledge. What is the smallest, simplest sentence you might form with each of these verbs?

cough

acknowledge

Here are my sentences:

They cough.

They acknowledge me.

You may have gone even simpler and omitted the subject, to make commands:

Cough!

Acknowledge me!

But, in these commands–technically called imperatives–we say there is still a subject, it is just unexpressed: it’s not just anybody who is being directed to cough or acknowledge; it is specifically the addressee (“you”). We can make this subject overt, and the meaning does not change:

You cough!

You acknowledge me!

Now, whether you included an overt subject in your sentences or not, I bet you did not come up with something like the following:

*They cough phlegm.

*They acknowledge.

These are (except in perhaps highly specific circumstances) not grammatical English sentences. [You could make the first one sound a lot better by adding the particle “up,” i.e. “They coughed up phlegm.” It is interesting to consider the difference in meaning between cough and cough up.]

While cough and acknowledge both need a subject, they differ in their other semantic requirements. Specifically, they differ in what we call the number of complements the verb needs.

The meaning of cough requires just one entity: someone coughing. We can say that cough has one complement: the subject.

The meaning of acknowledge requires two entities: someone acknowledging, and someone being acknowledged. A “sentence” with this verb is incomplete without someone being acknowledged as part of the sentence. Acknowledge requires two complements: a subject and a direct object (more on this later!).

Think of complement as something that completes a verb, or is complementary to it. I like to think of complements as what a verb needs to “be happy”–that is, to satisfy all the meanings it has to contribute to a clause.

To understand the structure of sentences produced by different verbs, we will first be drilling down further into the meanings different verbs express, which are what underlies different complement requirements. We’ll then get back to thinking about how these meanings manifest in different structures more in the next unit.

In other words, we’ll start with an overview of the semantics of verb phrases, then get technical about their syntax. We are ultimately working towards a typology of different clause types: basic patterns we see inside of verb phrases.

In a simple declarative sentence, a verb phrases expresses a proposition. Consider the following:

Beyoncé birthed twins.

Justin caused controversy.

The other Justin experienced a comeback.

Each of these sentences makes a proposition: a claim about the state of the world.

We have said that every clauses contains a subject and a predicate. We will now add that every predicate contains a predicator. The predicator is the head of the verb phrase–i.e. the main verb. To speak of it as a predicator is to focus in on its function as an element that predicates something of other entities.

(I am borrowing heavily here from Huddleston & Pullum’s Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. There are so many ways one could describe what happens in the verb phrase and I am trying to give you the right balance of simplicity and compexity.)

Semantically, each of the above propositions consists of a predicator and two complements. These are new terms which will help us break down how verbs carry different types of meanings, and ultimately how this results in different cause structures. The predicator predicates something of its complement(s).

Below, I rewrite the sentences from above with the predicator in red, and the complements in blue:

Beyoncé birthed twins.

Justin caused controversy.

The other Justin experienced a comeback.

In all of these cases the predicator is the verb. And the complements are all noun phrases. These are “typical” verbs that function to make some claim about a subject, and in all of these cases also about a second entity. “Birthed” is something that involves both Beyoncé and twins. We would say that “Birthed” is the predicator; “Beyoncé” and “twins” are both complements of “birthed.” Likewise, “caused” is a predicator; “Justin” and “controversy” are both complements of “caused.”

Notice that for these verbs, you cannot leave out one of the complements!

*Beyoncé birthed.

*Justin caused.

*The other Justin experienced.

These sentences are ungrammatical because the meaning carried by the verb is somehow incomplete. Birthing involves one giving birth and one (or more) being birthed. Caused involves one causing and one being caused. And experienced involves one doing the experience and the thing they are experiencing! So, in each of these sentences, the subject is a necessary but not sufficient part of the sentence. The verb still says “more,” about something besides the subject. Each required element that the verb “says something about” is a complement of the predicator.

Let’s zoom out even more and think about verbs in their most abstract form. What are the “entries” you have in your mind as to what each verb is, and how it works? When you choose a verb to use, your brain automatically generates a kind of template for how many complements it will need. “COUGH”? Your brain knows it only needs a subject. “CAUSE”? Your brain knows it needs a subject, plus a direct object. It doesn’t matter what tense the verb is in, or what else is in the sentence: at the most basic level, your brain is creating a sentence out of predicators and complements.

When children start putting words together, they start by putting together words that stand for basic concepts, which they are trying to express relationships between. They are doing predication! Here are some fairly random examples from my daughter’s multi-word acquisition stage:

- Mommy here

- roll dice

- I climbing

- I want phone

- No bird eat them

- I wear rainbow

- I ready

- Rocket ship too high

What is she predicating?

- Being here is predicated of Mommy

- roll is predicated of (someone) and dice

- climbing is predicated of I

- want is predicated of I and phone

- no eat is predicated of bird and them

- wear is predicated of I and rainbow

- Being too high is predicated of Rocket ship

When linguists talk about semantically different types of verbs, we refer to their complement structure: how many complements they have, and even more specifically, what relationship to the verb each complement has. In the sentence above, “Justin” bears a different relationship to caused than “controversy” does. This is why “Controversy caused Justin” means something totally different!

2. Basic clause functions and verb types

Each complement fulfills a certain function in the clause, and this corresponds to how it is related to the meaning of the predicator. The most canonical functions are subject and object. Subjects and objects are, most typically, realized as noun phrases.

Every verb requires a subject complement, and therefore the subject requirement is not useful for us to understand different types of verbs. The subject also always lies outside of the VP: this is part of our definition of both subject and predicate! A subject, therefore, is an external complement. It is external to the VP (or, if you like, to the predicate).

The other complements of a verb occur inside of the VP, and are therefore internal complements. And it is the internal complement requirements that differ across verb types. A basic distinction can be made between verbs that require at least one object and those that do not. Verbs that require an object are transitive; verbs that do not require an object are intransitive. There are also different types of objects: direct and indirect.

What are objects? Well, you know that the subject is the entity predicated of by the entire VP. In an ordinary transitive or ditransitive sentence, the subject is also the entity that “does” or “experiences” or “acts upon” another entity, and the direct and indirect object are “acted upon.” However, these vague definitions work best for concrete, action-laden verbs, and don’t work so well for verbs like “experience”! Nonetheless, to get started recognizing when you see an object, it can be useful to think of subjects as “actors” and objects as “acted upon” or “acted towards.”

Here are some example sentences that I have labeled according to these sentence functions. The verb/predicator is in red; the subject is in blue; the direct object is in green; the indirect object is in purple.

TRANSITIVE:

They kicked the ball far away.

The littlest one scored two goals.

INTRANSITIVE:

The soccer team played hard.

Active kids really sweat.

DITRANSITIVE:

Larry sold the family the condo.

That bank always offers people good rates.

Notice that there are a few words here in black: far away, hard, really, always. These are all adverb phrases, and they modify the verb or verb phrase. These modifiers are not complements: they are not crucial to the predication; they are entirely “optional” elements. It is conventional to call such optional items in a clause adjuncts. I will sometimes use this term, though I may also say adverbial or modifier! A clause can have an infinite number of adjuncts and this will have no bearing on how we analyze its verb type or clause structure!

As you look at these again, really think about how the different functions correspond to different relationships to the verb’s meaning:

The soccer team played hard.

PLAY:

the soccer team did the playing

Active kids really sweat.

SWEAT:

active kids do the sweating

They kicked the ball far away.

KICK:

They did the kicking

the ball is what was kicked

The littlest one scored two goals.

SCORE:

the littlest one did the scoring

two goals is what was scored

Larry sold the family the condo.

SELL:

Larry did the selling

the condo is what was sold

the family is who it was sold to

That bank always offers people good rates.

OFFER:

that bank does the offering

good rates are what is offered

people are who it is offered to

This is what I mean by how understanding the meanings of verbs in turn corresponds to different structures in the VP. Why does that VP look different from that other one? Why aren’t they all the same? Because different verbs have different types of meanings, which necessitates different complements. This, in turn, necessitates different structural patterns.

To sum up here, English has three most-canonical categories of verbs. As predicators, these have three different sets of complement requirements.

- Verbs like Cough do not have an object. We’ll call these intransitive verbs.

- sleep, arrive, sneeze, jump, live, die

- Verbs like Acknowledge have a direct object. We’ll call these transitive verbs.

- kick, see, lift, help, scrape, bite

- Verbs like Give have a direct object and indirect object. We’ll call these ditransitive verbs.

- buy, send, loan, cook, feed, offer

| Verb type | Internal complement | Internal complement realizations (typical) |

| intransitive | – | – |

| transitive | direct object | NP |

| ditransitive | indirect object + direct object | NP + NP |

Of course, things don’t stay this simple, and there are verbs with less canonical meanings, and with more complicated structures, to explore!

3. Predicative complements: nouns, adjectives, and prepositions

Consider the following sentences:

Lauren is a teacher.

The students were hilarious.

The book is in my office.

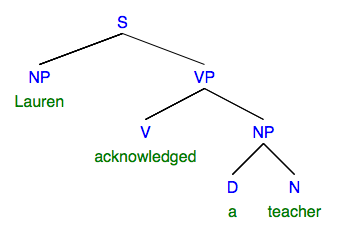

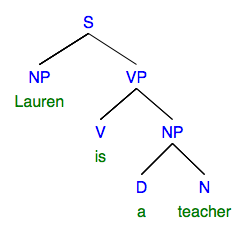

You’ll notice that these sentences all contain the verb BE. This is the verb whose inflected forms include is, were, are, am, been, and so on. If we take a sentence with Acknowledge as its verb and a sentence with BE as its verb, their phrase structure trees might look identical in *structure*:

Clearly, BE has an internal complement in the same way that ACKNOWLEDGE does. And “a teacher” is an NP in both cases. But it would be very strange to consider “a teacher” to be an object in both cases–a teacher being acknowledged is quite different from a teacher being…been? BE is a special verb, which warrants its own discussion, but it also shares properties with some other verbs that take similar internal complements.

Think about the relationship between the subject NP, the verb, and the NP in the VP in these sentences:

(a) Lauren acknowledged a teacher.

(b) Lauren is a teacher.

You can’t really paraphrase (b) like you can (a): they have totally different relationships to the subject. In (a), Lauren is doing something to Teacher, while in (b), Lauren simply IS Teacher—the relationship is one of identification or ascription, not involvement or action.

In (b), the quality being a teacher is what is predicated of Lauren. And it’s really the noun Teacher that performs the predication, not the verb BE, which itself doesn’t have much meaning. Nonetheless, a teacher is a complement of the verb BE: you cannot have a VP headed by BE without an internal complement!

*She was.

We will call a complement that itself performs some predication a predicative complement. A predicative complement will be realized as an NP, AdjP, or occasionally PP (when describing a locational state of being). A predicative complement can occur with a number of verbs, including the verb BE. Here are some more examples, with a couple of different verbs:

The baby is hungry.

The baby seems hungry.

The baby feels hot.

The baby is in her crib.

We call this use of BE as a main verb the copula. The term copula comes from Latin and is cognate with couple; they share the sense of “connecting.” If you have ever heard the term “linking verb,” this is where that idea comes from, that these verbs “link” the predicative element to the subject. This is just another (less technical) way of describing predication. When I say a baby is hungry, the primary meaning comes from the adjective hungry, not the verb is. In fact a child could say “Baby hungry!” and we know exactly what predication is being made, without the verb there.

The fact that the BE verb doesn’t really carry its own independent predicative meaning is one reason it has this special label of copula. Please be clear that no other verbs function as a copula! Repeating: “copula” is a technical term that does not apply to any verb but BE, and it only applies when BE is the clause’s main verb, not an auxiliary verb. The existence of the copula also highlights one reason why the old “it describes an action or event” definition of VERB is inadequate! The copula does no such thing. Other than when it is used to mean simply “in existence,” BE certainly does not indicate an action or event, or anything at all, really!

Other verbs, like seem and feel, do have some content of their own, though one could argue that the primary predication is still coming from the adjective phrase in the examples above! We compromise by calling them “predicative complements” 🙂

Also, remember when we talked about the attributive v. predicative functions of adjectives? Here we are again, but more formally! The adjectives in the predicative position are predicating of the subject.

We will call verbs and clauses that have no direct object, but a predicative complement, complex-intransitive. They are intransitive in the sense that they have no object. They are complex in the sense that they do nonetheless have a complement, which is predicative in nature. So, we can now add a fourth category of verb/clause type to the three we had above:

- Verbs like Cough do not have an object. We’ll call these intransitive verbs.

- sleep, arrive, sneeze, jump, live, die

- Verbs like Acknowledge have a direct object. We’ll call these transitive verbs.

- kick, see, lift, help, scrape, bite

- Verbs like Give have a direct object and indirect object. We’ll call these ditransitive verbs.

- buy, send, loan, cook, feed, offer

- Verbs like Seem have a predicative complement, which predicates of the subject, but no object. We’ll call these complex-intransitive verbs.

- seem, feel, remain, become, prove, got

- BE

The verb types so far can be summarized:

| Verb type | Internal complement | Internal complement realizations (typical) |

| intransitive | – | – |

| transitive | direct object | NP |

| ditransitive | indirect object + direct object | NP + NP |

| complex intransitive | predicative complement | AdjP/NP/PP |

There is one final “basic” (but not so basic) type of verb/clause that I want you to know about. Note that these do not exhaust the types of verbs and clauses, but only represent the most common, and with the most number of individual verbs within them! There are many “one-off” verbs that have very specific complement requirements, which are atypical. When you come across something that doesn’t fit one of these patterns, it may just be a “special” kind of verb 🙂

We have seen a basic distinction between transitive and intransitive verbs: whether there is a direct object or not. We have also seen that some intransitive verbs do not have a direct object, but do have another kind of complement. The final kind of verb we will look at has both a direct object AND another kind of complement! Consider:

They considered the story believable.

Halloween makes some parents nervous.

The voters elected her President.

If you try to analyze these as simple transitive verbs, you will be left with something “extra” in the verb phrase, in addition to the direct object. Here, I underline the direct objects:

They considered the story believable.

Halloween makes some parents nervous.

The voters elected her President.

The story is being considered, some parents are being made, and her is being elected–but there is an additional element here that must be accounted for! What are believable, nervous, and President doing?

These are in fact, another predicative kind of complement within the VP. Notice that these are not optional elements; they are required complements. Removing them either makes the sentence ungrammatical, or changes the sense of the verb however slightly:

They considered the story

Halloween makes some parents

The voters elected her

We know that these have to be complements. Unlike the predicative complements in the complex-intransitive examples, these predicate something of the direct object, not of the subject. We will call these complex-transitive verbs.

“Being believable” is predicated of “the story,” not “they.”

“Being nervous” is predicated of “some parents,” not “Halloween.”

And “President” is predicated of “her,” not “the voters.”

So these complements are predicating something of the direct object. Wild, right?

Thus completes (!) our 5 basic verb/clause types. We’ll spend a good deal of time practicing identifying these!

- Verbs like Cough do not have an object. We’ll call these intransitive verbs.

- sleep, arrive, sneeze, jump, live, die

- Verbs like Acknowledge have a direct object. We’ll call these transitive verbs.

- kick, see, lift, help, scrape, bite

- Verbs like Give have a direct object and indirect object. We’ll call these ditransitive verbs.

- buy, send, loan, cook, feed, offer

- Verbs like SEEM have a predicative complement, which predicates of the subject, but no object. We’ll call these complex-intransitive verbs.

- seem, feel, remain, become, prove, got

- BE

- Verbs like CONSIDER have a direct object and a predicative complement, which predicates of the direct object. We’ll call these complex-transitive verbs.

- make, judge, elect, prove, find, call

| Verb type | Internal complement | Internal complement realizations (typical) |

| intransitive | – | – |

| transitive | direct object | NP |

| ditransitive | indirect object + direct object | NP + NP |

| complex-intransitive | predicative complement | AdjP/NP/PP |

| complex-transitive | direct object + predicative complement | NP + AdjP/NP/PP |

4. Test Yourself: Quiz for Module 7, Basic Unit

[in progress, check back!]